Transfer Pricing in Japan: Residual Profit Split Method and the Role of Non-Intangible Factors

TL;DR

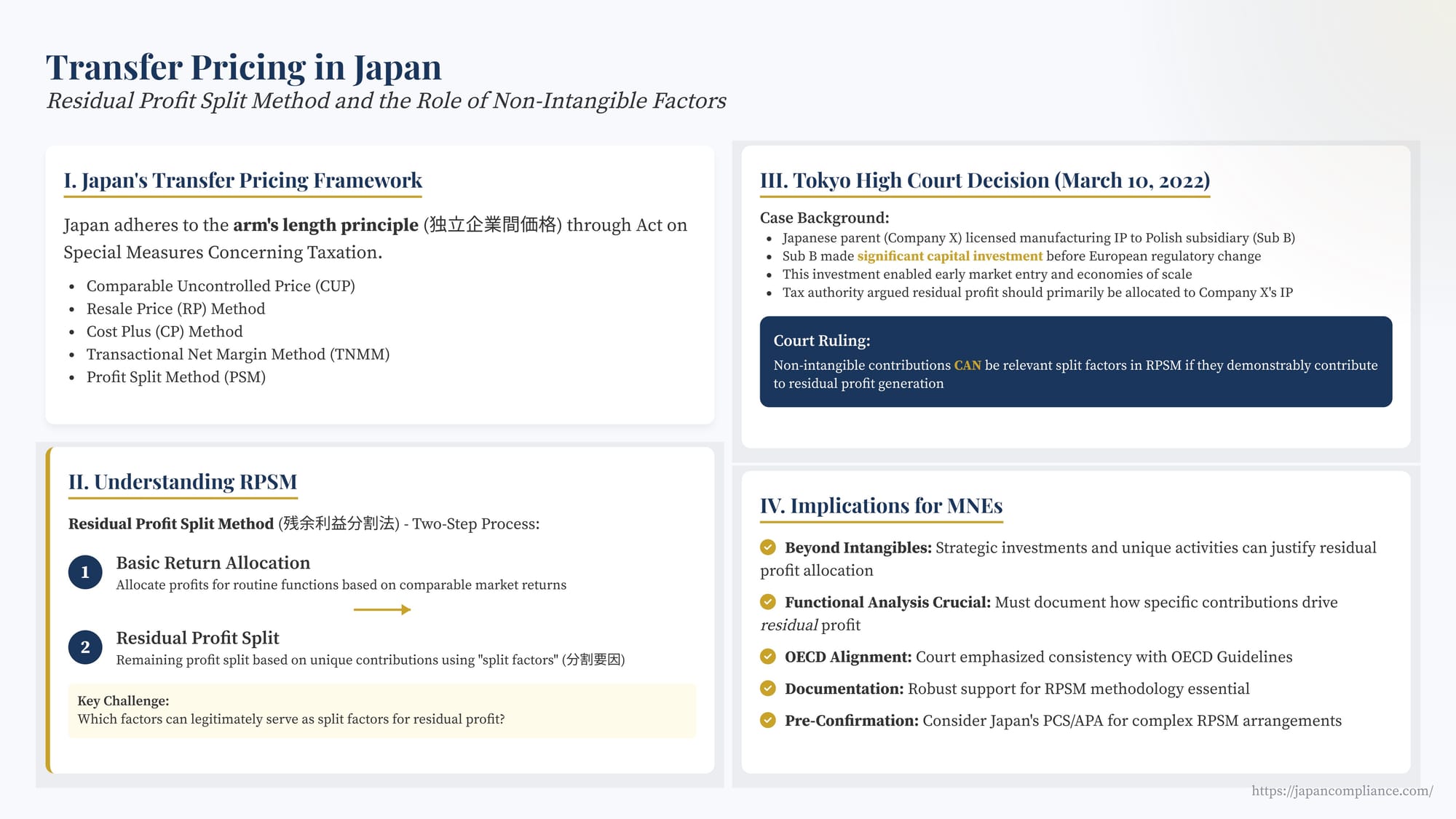

- Japan applies the OECD-aligned Residual Profit Split Method (RPSM) when both related parties make unique, valuable contributions.

- Tokyo High Court (10 Mar 2022) ruled that non-intangible factors—e.g., large, strategic capital investments—can justify a share of residual profit if they demonstrably drive non-routine returns.

- Taxpayers must prove the causal link between such investments and residual profit; robust functional analysis and documentation are critical.

- The decision underscores the importance of comprehensive RPSM design and, where possible, securing certainty via Japan’s Pre-Confirmation System (APA).

Table of Contents

- Japan’s Transfer-Pricing Framework and the Arm’s Length Principle

- Understanding the Profit Split Method (PSM) and RPSM

- The Core Issue: Can Non-Intangibles Drive Residual Profit?

- Case Study: Tokyo High Court, 10 Mar 2022

- Significance and Implications for MNEs

- Conclusion

Transfer pricing remains a critical area of focus for multinational enterprises (MNEs) operating in Japan and for the Japanese tax authorities (National Tax Agency - NTA). Ensuring that transactions between related parties adhere to the arm's length principle is paramount. Japan's transfer pricing regulations, primarily found within the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation (租税特別措置法 - Sozei Tokubetsu Sochi Hou), provide several methods for determining arm's length pricing, broadly aligning with the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines.

Among these methods, the Profit Split Method (PSM), and particularly the Residual Profit Split Method (RPSM or 残余利益分割法 - zan'yo rieki bunkatsu hou), is often considered for complex transactions where both related parties make unique and valuable contributions, especially involving intangible property. Historically, there has been debate regarding the factors considered when splitting the "residual" profit under RPSM. A key question has been whether contributions other than formal intangible assets, such as significant strategic investments in tangible assets, can justify an allocation of residual profit. A Tokyo High Court decision from March 10, 2022 (Reiwa 4), provides important clarification, affirming that non-intangible factors can be relevant profit drivers under RPSM in Japan, provided their contribution to residual profit is substantiated.

Japan's Transfer Pricing Framework and the Arm's Length Principle

Like most developed economies, Japan adheres to the arm's length principle as the standard for evaluating transfer pricing between related entities. This means that the conditions (especially pricing) of transactions between associated enterprises should be consistent with those that would have been agreed upon between independent enterprises in comparable circumstances.

To determine the arm's length price (独立企業間価格 - dokuritsu kigyoukan kakaku), Japanese regulations recognize the standard transfer pricing methods outlined in the OECD Guidelines:

- Comparable Uncontrolled Price (CUP) Method

- Resale Price (RP) Method

- Cost Plus (CP) Method

- Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM)

- Profit Split Method (PSM)

The selection of the most appropriate method depends on the specific facts and circumstances of the transaction, the availability of reliable comparable data, and the nature of the contributions made by each party. While the NTA often favors traditional transaction-based methods or TNMM where applicable, the PSM is recognized as appropriate in specific, complex situations. The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines are highly influential in the interpretation and application of these methods in Japan.

Understanding the Profit Split Method (PSM) and RPSM

The PSM is generally applied when transactions are highly integrated, making it difficult to evaluate them separately, and when both related parties make unique and valuable contributions (often involving intangibles) for which reliable comparable data for one-sided methods (like TNMM) cannot be found. The PSM seeks to allocate the combined profit (or loss) from the controlled transaction(s) between the associated enterprises based on their relative contributions.

The Residual Profit Split Method (RPSM) is a specific application of the PSM, typically involving two steps:

Step 1: Allocation of Basic (Routine) Return

- First, a portion of the combined profit is allocated to each participant to provide a basic return for the routine functions they perform, assets they use, and risks they assume.

- This basic return is typically determined by reference to market returns achieved by comparable independent companies engaged in similar routine activities. Methods like TNMM or the Cost Plus method are often used at this stage to benchmark the routine profit allocation.

Step 2: Allocation of Residual Profit

- Any profit (or loss) remaining after the allocation of basic returns in Step 1 is considered the "residual profit." This residual profit is deemed to be generated by the parties' unique and valuable contributions, often linked to intangible assets or significant risk-taking.

- This residual profit is then split between the associated enterprises based on an analysis of their relative contributions to generating that residual profit.

The Challenge: Determining Split Factors (分割要因 - bunkatsu youin)

The most challenging aspect of RPSM is Step 2 – determining the basis for splitting the residual profit. The allocation should reflect the relative value of each party's unique and valuable contributions. The factors used to approximate this relative value are known as "split factors."

Commonly considered split factors often relate to the development and exploitation of intangible property, such as:

- Research and Development (R&D) expenses

- Marketing, Advertising, and Promotion (MAP) expenses

- The value of assets employed (including intangibles)

- Headcount or personnel costs related to key functions

The selection of appropriate split factors requires careful functional analysis and economic reasoning to reliably reflect the relative contributions to the residual profit. This determination is often subjective and can be a major source of disagreement between taxpayers and tax authorities. Given this complexity, MNEs often seek certainty for their RPSM methodologies through Japan's Pre-Confirmation System (PCS or 事前確認制度 - jizen kakunin seido), equivalent to an Advance Pricing Agreement (APA).

The Core Issue: Can Non-Intangibles Drive Residual Profit?

A key point of contention, highlighted by the 2022 Tokyo High Court case, revolves around the types of contributions considered relevant for splitting the residual profit in Step 2 of RPSM.

Historically, perhaps influenced by administrative guidance (like the former Circular 66-4(4)-5 mentioned in legal commentary), there was a tendency for tax authorities to heavily emphasize contributions related to "significant intangible property" (重要な無形資産 - juuyou na mukei shisan) as the primary, or even sole, drivers of residual profit. This raised the question: Can other types of contributions, such as substantial investments in tangible assets or strategic market development activities enabled by such investments, also be considered drivers of residual (non-routine) profit and thus serve as valid split factors?

Case Study: Tokyo High Court, March 10, 2022 (Reiwa 4)

This case involved a Japanese parent company ("Company X") and its wholly-owned Polish subsidiary ("Sub B").

Facts (Generalized):

- Company X, a Japanese corporation, owned valuable intangible property (IP) related to the manufacture of a specific high-tech automotive component (diesel particulate filters).

- Company X licensed this IP to Sub B in Poland.

- Sub B used the licensed IP to manufacture and sell the components primarily in the European market.

- Anticipating upcoming stricter European emissions regulations that would significantly boost demand for the product, Sub B undertook significant and timely capital investment ("the Capital Investment") to build state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities in Poland before the regulations took effect.

- When demand surged as predicted, Sub B's early investment allowed it to rapidly scale up production, achieve economies of scale, and capture significant market share, resulting in substantial profits.

- The Japanese tax authority challenged the arm's length nature of the royalty payments from Sub B to Company X. Using the RPSM, the authority argued that the residual profit, after allocating routine returns, should primarily be allocated to Company X based on its ownership of the crucial manufacturing IP.

- Company X countered that Sub B's strategic and substantial Capital Investment was a key contributing factor to the generation of the residual profit. They argued this investment enabled early market entry and large-scale production efficiencies that went beyond a mere routine manufacturing return, and therefore, factors related to this investment (specifically, depreciation expenses associated with it) should be included as a split factor in allocating the residual profit.

- The tax authority maintained that under RPSM, residual profit splitting should fundamentally be based on contributions related to significant intangibles, and considering factors like tangible asset depreciation would inappropriately dilute the return attributable to Company X's IP.

The High Court's Decision:

The Tokyo High Court upheld an earlier District Court ruling in favor of the taxpayer (Company X), confirming that factors other than intangible property can indeed be considered when splitting residual profit under RPSM. The court's reasoning was multi-faceted:

- Rejection of Intangible-Only Focus: The court explicitly rejected the tax authority's narrow view that RPSM residual splits are essentially limited to contributions from significant intangibles (Judgment Point I & V).

- Statutory Basis (PSM Definition): It referred to the definition of the PSM in the relevant Japanese Cabinet Order (at the time, Art. 39-12, Para. 8, Item 1 of the Order for Enforcement of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation). This definition broadly states that profits should be allocated according to factors that reliably estimate the degree of contribution to profit generation, explicitly mentioning "amount of expenses disbursed" and "value of fixed assets used" as potential factors (Judgment Point II).

- Administrative Guidance: The court noted that the applicable administrative circular (at the time, Circular 66-4(4)-2) also listed factors like personnel expenses and "amount of invested capital" as suitable split factors, further supporting a broader view than just intangibles (Judgment Point III).

- Consistency with OECD Guidelines: Crucially, the court relied heavily on the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines (referencing both the 2010 and 2017 versions and finding consistency on this point). It highlighted the Guidelines' principle that the split of residual profit (Step 2) should be based on an analysis of the specific facts and circumstances surrounding each party's contributions, without being restricted solely to intangible assets (Judgment Point IV).

- Conclusion on Principle: Based on domestic law and its interpretation consistent with OECD Guidelines, the court concluded that if a factor other than significant intangible property is shown to reliably reflect a party's contribution to the generation of residual profit, it is permissible and appropriate to use it as a split factor in RPSM.

Application to the Specific Facts:

While establishing this important principle, the High Court's decision was grounded in the specific facts found by the lower court. It was the detailed finding that Sub B's specific, large-scale, and strategically timed Capital Investment directly enabled its early market entry and achievement of economies of scale – factors contributing significantly to profits beyond a routine manufacturing return – that justified using related depreciation as a split factor in this case. The ruling should not be interpreted as automatically allowing all capital investment depreciation to be used as a split factor; a clear causal link to the generation of residual profit must be demonstrated.

The court also dismissed the tax authority's argument that strategic decisions made by the parent company should, by default, result in residual profit being allocated to the parent. This affirms that profit allocation should be based on functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed, rather than solely on hierarchical position within the MNE group.

Significance and Implications for MNEs

The Tokyo High Court's decision offers valuable guidance for MNEs using or considering RPSM for their Japanese transfer pricing:

- Beyond Intangibles: The ruling confirms that the NTA and Japanese courts, aligning with OECD principles, can accept profit split factors beyond formal IP contributions. Strategic investments, market development activities, unique risk-taking, or other contributions can potentially justify an allocation of residual profit if their link to that profit is clearly established and documented.

- Functional Analysis is Paramount: The decision underscores the absolute necessity of a thorough functional analysis for RPSM. Taxpayers must meticulously identify all significant contributions made by each related party, analyze how those contributions interact, and demonstrate how they specifically drive the generation of residual profit (i.e., profit exceeding routine returns). Simply owning valuable IP is not enough.

- Alignment with OECD Guidelines: The case reinforces the critical role of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines in interpreting and applying Japan's domestic transfer pricing rules. MNEs should strive for consistency between their global transfer pricing policies and OECD principles when dealing with their Japanese operations.

- Robust Documentation Essential: MNEs employing RPSM must maintain detailed documentation supporting their methodology. This documentation should clearly explain the functions, assets, and risks of each party, the rationale for selecting RPSM, the calculation of routine returns, the identification of unique contributions driving residual profit, and the justification for the chosen split factors, demonstrating their reliable connection to residual profit generation.

- Potential for Disputes Persists: While providing clarity on the principle, the case also illustrates that determining which contributions genuinely drive residual profit and selecting appropriate split factors remains inherently complex and potentially contentious. This further highlights the value of considering Japan's Pre-Confirmation System (PCS/APA) to gain advance certainty for complex RPSM arrangements.

Conclusion

The March 2022 Tokyo High Court decision sends a clear message: the application of the Residual Profit Split Method in Japan requires a comprehensive assessment of all significant contributions driving non-routine profits, not just those related to formal intangible property. Strategic tangible investments, market positioning activities, or other unique functions can be valid bases for allocating residual profit, provided their impact is factually substantiated and reliably measured. This ruling aligns Japanese practice more explicitly with the principles of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, emphasizing the need for MNEs to conduct thorough functional analyses and maintain robust documentation to support their RPSM methodologies involving Japanese affiliates.