Transfer of Assets or Gratuitous Act? The Japanese Supreme Court on Capital Gains Tax in Divorce Settlements

Case: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of May 27, 1975 (Showa 47 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 4: Action for Rescission of Income Tax Reassessment Disposition)

Introduction

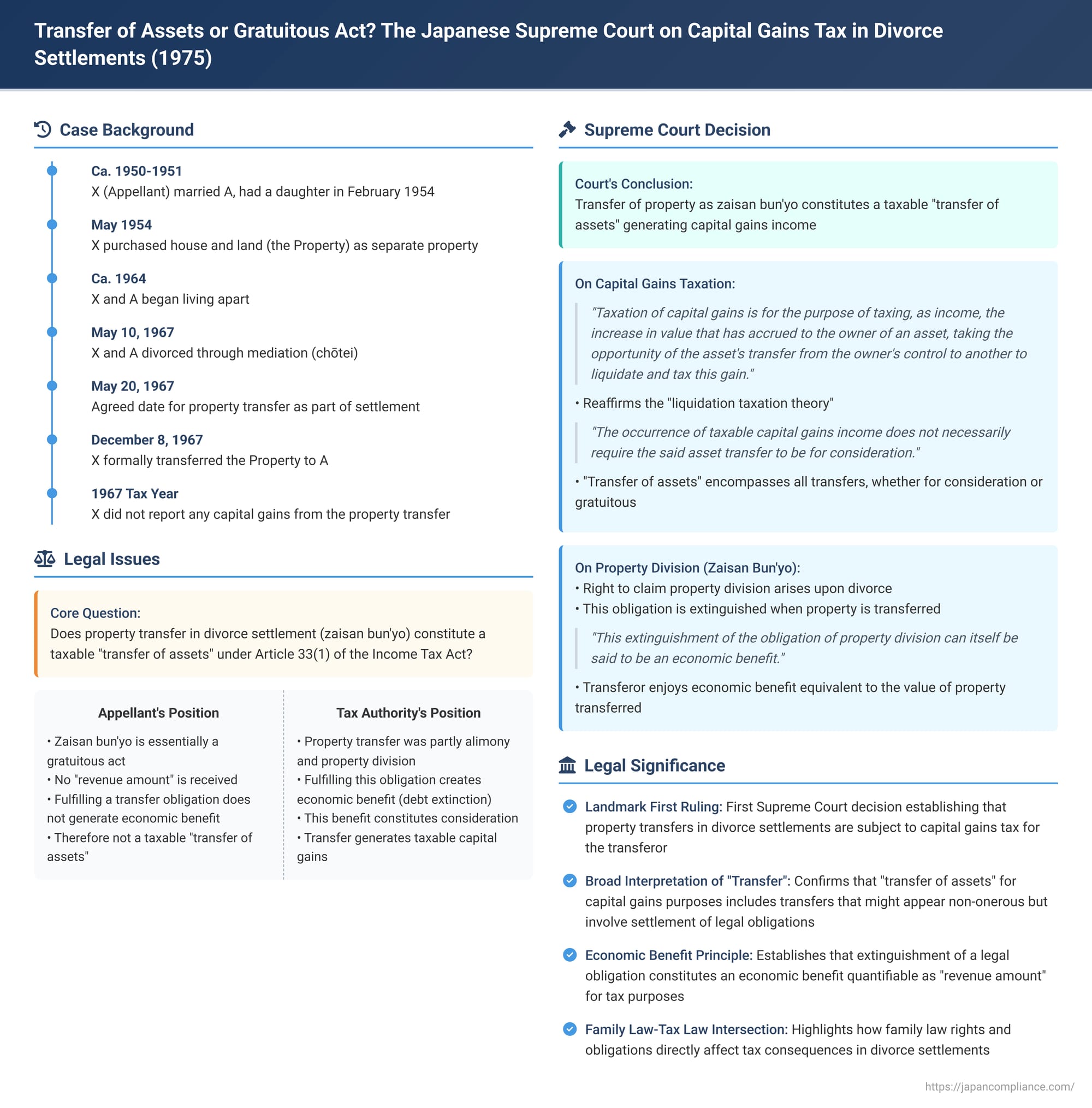

On May 27, 1975, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision concerning the income tax implications of transferring property as part of a divorce settlement. This case addressed whether such a transfer, known in Japanese law as zaisan bun'yo (財産分与), constitutes a taxable "transfer of assets" (資産の譲渡, shisan no jōto) that gives rise to capital gains income for the spouse making the transfer. The appellant argued that zaisan bun'yo is essentially a gratuitous act and should not trigger capital gains tax. The Supreme Court's ruling provided crucial clarification, establishing that such transfers generally are taxable events, based on the "liquidation taxation theory" of capital gains and the economic benefit derived from the extinguishment of the property division obligation.

The core issue was the interpretation of "transfer of assets" under Article 33, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act in the context of a divorce, where property owned by one spouse is transferred to the other as part of a comprehensive settlement that can include elements of alimony, compensation, and division of marital property.

Facts of the Case

- Background: The appellant, X, married A around 1950 or 1951. They had a daughter in February 1954. In May 1954, X purchased a house and land (hereinafter "the Property"). It was undisputed that the Property was X's separate property, not jointly owned. Around 1964, X and A began living apart. In 1967, X initiated divorce mediation proceedings, and a divorce was formally agreed upon through mediation on May 10, 1967.

- Divorce Settlement Terms: The mediation record (調停調書, chōtei chōsho) stipulated the terms of the divorce settlement, which included:

- X was to transfer the Property and a telephone subscription right to A as alimony (慰謝料, isharyō). The ownership transfer registration for the Property was to be completed by May 20, 1967. X was also to pay A a sum of 14.5 million yen in cash.

- X was to pay monthly child support of 30,000 yen for their daughter from May 1967 until April 1977.

- Property Transfer and Tax Filing: X completed the property registration, transferring ownership of the Property to A on December 8, 1967, with the cause of transfer stated as "transfer due to alimony," effective May 20, 1967. In his income tax return for the 1967 tax year, X declared his total income as 7,937,627 yen, comprising business income (7,756,215 yen) and employment income (181,412 yen). He did not declare any capital gains income arising from the transfer of the Property.

- Tax Authority's Reassessment: The director of the competent tax office, Y (the appellee), determined that X had failed to report capital gains income from the transfer of the Property to A on May 20, 1967. Y reassessed X's income, adding 1,488,877 yen as capital gains income, bringing the total assessed income to 9,426,504 yen. Y also imposed an underpayment penalty.

- Legal Challenge and Lower Court Rulings: X contested the reassessment through administrative appeals and subsequently filed a lawsuit. His primary argument was that a "transfer of assets" that triggers capital gains income under Article 33, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act implies an onerous transfer (a transfer for consideration). He contended that the transfer of the Property was, in substance, a zaisan bun'yo (property division) and therefore a gratuitous act, not falling under the definition of a taxable "transfer of assets".

- The Nagoya District Court (court of first instance) dismissed X's claim. It found that the Property was transferred as alimony, which is not a gratuitous transfer, and thus constituted a taxable capital gain.

- X appealed to the Nagoya High Court, arguing that the Property transfer also included elements of zaisan bun'yo. The High Court also ruled against X. It determined that X had agreed to transfer the Property as alimony and property division, and by fulfilling this obligation, X enjoyed an economic benefit – the extinguishment of his debt (obligation to make the transfer). This, the High Court reasoned, was no different in economic terms from receiving actual consideration, and thus the transfer gave rise to taxable capital gains income under Article 33, Paragraph 1.

- X's Arguments to the Supreme Court: X appealed to the Supreme Court, reiterating and elaborating on his arguments:

- A transfer of assets not accompanied by consideration (including any reciprocal payment or similar economic benefit) does not involve "revenue amount" (収入金額, shūnyū kingaku) as contemplated by the Old Income Tax Act Article 9, Paragraph 1, Item 8 (the predecessor to the current Article 33).

- When an asset transfer is made in lieu of payment for a pre-existing debt arising from other legal causes, an economic benefit might be recognized (i.e., avoiding the asset reduction that would have occurred from satisfying the debt as originally intended). However, if a person incurs an obligation to transfer asset ownership due to a contract (like a sale or gift) and then fulfills that obligation, this merely completes the purpose of the contract and does not, in itself, generate an economic benefit from the act of fulfillment.

- The portion of the Property transfer made as zaisan bun'yo was merely the fulfillment of an obligation (to transfer the target property) that X assumed through the mediation agreement. As such, X enjoyed no economic benefit from this act of fulfillment, and therefore, it did not constitute an onerous transfer subject to tax under Article 33.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the High Court's conclusion that the transfer was a taxable event. The Court's reasoning was rooted in the nature of capital gains taxation and the legal characterization of zaisan bun'yo.

The Nature of Capital Gains Taxation (Reaffirming the Liquidation Taxation Theory)

The Court first laid down its established understanding of capital gains taxation:

- "Taxation of capital gains is for the purpose of taxing, as income, the increase in value that has accrued to the owner of an asset, taking the opportunity of the asset's transfer from the owner's control to another to liquidate and tax this gain". This is a clear affirmation of the "liquidation taxation theory."

- Crucially, the Court stated: "Therefore, the occurrence of taxable capital gains income does not necessarily require the said asset transfer to be for consideration". In support of this, the Court referenced its earlier decision in the Akahoshi case (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, December 26, 1972; Minshu Vol. 26, No. 10, p. 2083 – discussed as Case 41 in the source material series).

- Based on this premise, the Court concluded: "Consequently, 'transfer of assets' in Article 33, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act should be interpreted as encompassing all acts of transferring assets, whether for consideration or gratuitously".

- The Court also briefly noted that Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act (the old version, pre-1973 amendment, which dealt with special rules for calculating gross revenue in certain transfers like gifts to corporations at fair market value) was a special provision for calculating the revenue amount for capital gains and did not itself create a taxable capital gain where one would not otherwise exist.

The Nature of Zaisan Bun'yo (Property Division Upon Divorce)

The Court then addressed the legal nature of zaisan bun'yo:

- "When a couple divorces, one party can claim property division from the other (Civil Code Article 768, Article 771)".

- "The specific content of this right to property division and the corresponding obligation is determined by the parties' agreement, family court mediation or judgment, or district court judgment. However, the right and obligation themselves arise upon the establishment of divorce and exist as substantive rights and obligations; the said parties' agreement, etc., merely determines their content concretely".

- "Then, when an agreement on property division is reached and its content is concretely determined, and division is completed accordingly through payment of money, transfer of real estate, etc., the said obligation of property division is extinguished".

- The Court then made a pivotal assertion: "This extinguishment of the obligation of property division can itself be said to be an economic benefit".

- "Therefore, when assets such as real estate are transferred as property division, the transferor should be said to have enjoyed an economic benefit in the form of the extinguishment of the obligation of property division".

Conclusion on X's Case

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's judgment, which found that the zaisan bun'yo portion of the Property transfer generated capital gains income for X and was subject to taxation, was "correct in its conclusion". X's arguments were, therefore, not accepted.

Commentary Insights

This 1975 Supreme Court decision is a foundational ruling in Japanese tax law concerning the taxability of property transfers made during divorce proceedings.

Significance of the Ruling

The commentary accompanying the case highlights its importance:

- "This judgment was the first Supreme Court decision to explicitly state that a transfer of assets as zaisan bun'yo is subject to capital gains taxation for the transferor".

- "This position has been consistently followed in subsequent Supreme Court rulings (e.g., Feb 16, 1978; July 10, 1978; Sept 14, 1989) and is now established case law". This principle is also reflected in "Income Tax Basic Directive 33-1-4". (The commentary notes that some of the cited subsequent cases dealt with facts arising before a 1973 amendment to Article 59 of the Income Tax Act).

- "Part I of the judgment (on the nature of capital gains) reaffirms the stance of previous precedents" (though citing a case under the Old Income Tax Act). "Part II (on the economic benefit from zaisan bun'yo) states that the transfer of assets as property division is accompanied by a revenue amount (including the value of economic benefits other than money, see Income Tax Act Art. 36(1))".

Liquidation Taxation Theory and the Requirement of Consideration

The commentary underscores that according to the liquidation taxation theory adopted in Part I of the judgment, "if a transfer of assets is recognized, it falls under 'transfer of assets' in Article 33, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act, regardless of the presence or absence of 'consideration' (an economic benefit received as remuneration for transferring the asset; see also Income Tax Act Art. 59(1)(2))". "For the meaning of capital gains income, refer to Case 41 (the Akahoshi case) which is cited in this judgment".

Zaisan Bun'yo and "Transfer of Assets" – The Underlying Property Rights

The nature of zaisan bun'yo itself is complex. "Property division upon divorce (Civil Code Art. 768(1), 771) can encompass various elements: (1) liquidation and distribution of substantive joint property acquired during the marriage; (2) post-divorce maintenance for the other party; (3) compensation for emotional distress suffered by the other party; and (4) settlement of marital expenses excessively borne by the other party" (citing several Supreme Court civil cases).

- A "strong argument exists that if zaisan bun'yo pertains solely to element (1) – the liquidation of substantively joint property – it is merely the attribution of a spouse's latent share to that spouse and does not constitute a 'transfer of assets' from the nominal owner, but rather a division of co-owned property" (citing scholars Hiroshi Kaneko and Tadatsune Mizuno).

- However, "Japanese law adopts a system of separate property for spouses (Civil Code Arts. 755, 762(1))". A "Supreme Court Grand Bench decision of September 6, 1961 (Case 30 in this series) stated that 'the Civil Code separately provides for rights such as the right to claim property division, inheritance rights, and the right to claim support, and legislative consideration has been given to ensure that no substantive inequality arises between spouses in return for their mutual cooperation and contribution by allowing them to exercise these rights'".

- "Therefore, even if property was acquired in one spouse's name during the marriage through the cooperation or contribution of the other spouse, it is considered the separate property (特有財産, tokuyū zaisan) of the nominal owner, and transferring it to the other spouse constitutes a 'transfer of assets'" (citing a Supreme Court judgment from January 24, 1995).

- "An exception exists: if property registered solely in one spouse's name is proven to be de facto co-owned with the other spouse, then transferring the other spouse's co-ownership share is not considered a 'transfer of assets' by the nominal owner" (citing a Supreme Court civil case from July 14, 1959, a High Court tax case, and Income Tax Basic Directive 33-1-7). "This is a matter of factual determination, and there are numerous court decisions and administrative rulings on this point".

Economic Benefit Arising from Zaisan Bun'yo

Regarding the nature of the right to claim zaisan bun'yo, Japanese case law generally follows the "gradual formation theory" (段階的形成権説, dankaiteki keiseiken setsu). "This theory posits that the right to claim property division before agreement or court order is an undefined right whose specific content needs determination; it becomes a defined right to property division through such agreement or order" (citing a Supreme Court civil case from July 11, 1980). "The Supreme Court's stance is that this right to claim property division arises as a substantive private right upon the establishment of divorce, even if its scope and content are initially undetermined and unclear. Part II of the present judgment is premised on this understanding".

The commentary emphasizes that the reasoning in Part II of the judgment (regarding the economic benefit from extinguishing the division obligation) "is valid when the transfer of assets is recognized as being 'as property division'" (citing a Tokyo District Court case from October 28, 1997). "For example, if assets transferred under the guise of property division are excessively large, the portion deemed excessive does not extinguish any 'division obligation,' and the reasoning of Part II would not extend to such an excessive portion" (citing Supreme Court civil cases and Inheritance Tax Basic Directive 9-8).

Revenue Amount for the Transferor and Acquisition Cost for the Transferee

The commentary further explains the financial implications:

- "Since the transferor enjoys an economic benefit (the extinguished 'division obligation') equivalent to the value of that obligation, and this is considered equal to the value of the asset transferred, the 'revenue amount' (under Income Tax Act Art. 33(3)) for the transferor is the fair market value of the asset at the time of transfer" (citing Income Tax Act Art. 36(1), (2)).

- For the "transferee (the recipient spouse), when they subsequently transfer the asset received as property division, their acquisition cost (under Income Tax Act Art. 38(1)) for calculating capital gains" is a related issue. A "Tokyo District Court judgment of February 28, 1991, held that the recipient spouse 'acquires the said asset in exchange for extinguishing their right to claim property division, which is an economic benefit. Therefore, the amount required for the acquisition of that asset is, in principle, equal to the value of the said right to claim property division'" (also referencing Income Tax Basic Directive 38-6). That District Court case, after detailed factual findings, "recognized an acquisition cost for the recipient that differed from the revenue amount recognized for the transferor in the transferor's income tax assessment review".

Broader Implications and Discussion

This 1975 Supreme Court decision has several wide-ranging implications:

- Broad Scope of "Transfer of Assets": The ruling confirms that "transfer of assets" for capital gains tax purposes is a broad concept, not limited to typical sales or exchanges for direct monetary consideration. It can include transfers that might appear non-onerous from a common-sense perspective but involve the settlement of legal obligations.

- Extinguishment of Obligation as Economic Benefit: A key principle affirmed is that the extinguishment of a legal obligation (such as the obligation to make property division upon divorce) constitutes an economic benefit to the person relieved of that obligation. This benefit can then be treated as the "revenue amount" or "proceeds" for capital gains tax purposes.

- Interplay of Family Law and Tax Law: The case highlights the intricate connection between family law principles (governing divorce, marital property rights, and property division) and tax law. The rights and obligations arising under family law directly influence the tax consequences of actions taken by divorcing spouses.

- Importance of True Property Ownership: Determining the true nature of marital property (whether it is genuinely separate property of one spouse or de facto co-owned) is crucial. If property is already co-owned in substance, its division according to respective shares may not constitute a taxable "transfer" for the portion already belonging to a spouse.

The "Considerations for Discussion" in the provided commentary raise further complex questions, such as the tax implications if a pre-existing gift agreement is settled through a property division transfer, or how to determine revenue and acquisition cost if the property division obligation agreed upon exceeds the value of the specific asset transferred to satisfy it.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's May 27, 1975, judgment established a critical precedent in Japanese tax law by holding that the transfer of assets as part of a zaisan bun'yo (property division upon divorce) is generally a taxable event giving rise to capital gains income for the transferor. This decision is grounded in the liquidation taxation theory, which focuses on the realization of accrued asset appreciation upon transfer, and the principle that the extinguishment of the legal obligation to divide property constitutes a quantifiable economic benefit to the transferor. This ruling underscores the importance of considering potential tax liabilities when property is transferred in the context of divorce settlements in Japan.