Trademark Similarity in the Real World: The Daishinrin Case and 'Actual Trade Circumstances' in Infringement

Judgment Date: September 22, 1992

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 3 (O) No. 1805 (Trademark Infringement Injunction Claim)

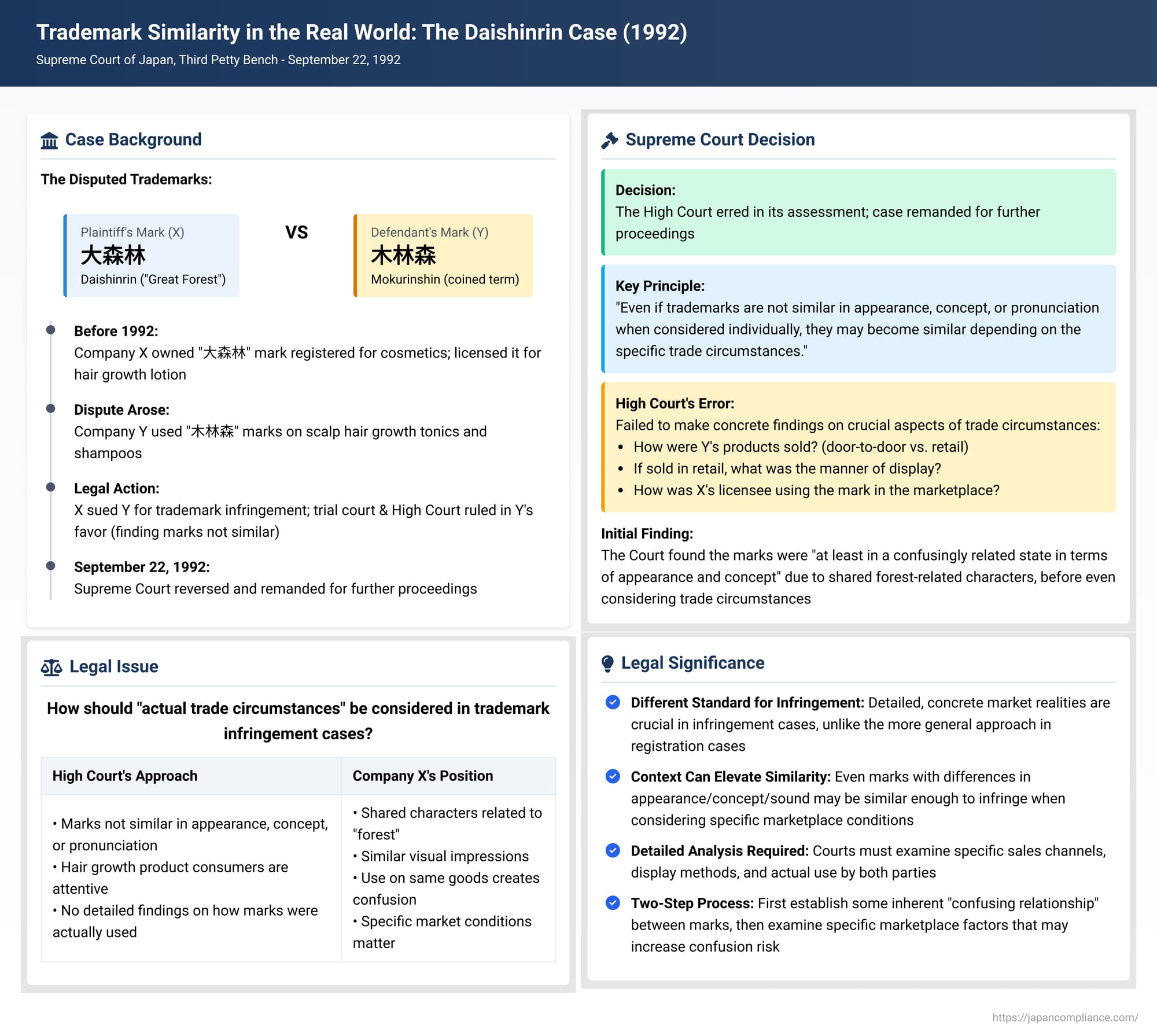

The "Daishinrin" (大森林 - Great Forest) case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1992, offers significant insights into how "actual circumstances of trade" (取引の実情 - torihiki no jitsujō) are to be considered when determining trademark similarity, particularly within the context of trademark infringement litigation. While building on principles established for registration proceedings (like in the Hyozan-jirushi case), the Daishinrin judgment emphasized a more granular and concrete examination of how the specific marks involved are used and encountered in the marketplace when assessing infringement.

The Marks and the Dispute: A Tale of Two Forests

The appellant, Company X, was the owner of a registered trademark consisting of the kanji characters "大森林" (Daishinrin, meaning "Great Forest"). This mark was written horizontally in a standard block script (楷書体 - kaisho-tai) and was registered for designated goods in Class 4, including "soaps, dentifrices, cosmetics, and perfumery." Company X had granted a non-exclusive license for this trademark, and the licensee was using the "大森林" mark on a medicated scalp hair growth lotion, which was then sold through its affiliated companies.

The appellee, Company Y, was engaged in the manufacturing and sale of cosmetics. It was using marks consisting of the kanji characters "木林森" (Mokurinshin – a coined term using characters for "tree," "woods/grove," and "forest/woods") on its scalp hair growth tonics and shampoos ("Y products"). These "Y marks" were written in a semi-cursive script (行書体 - gyōsho-tai) and appeared both vertically and horizontally on products and in advertisements.

Company X sued Company Y for trademark infringement, seeking an injunction to stop the manufacture and sale of Y products bearing the "木林森" marks. The trial court had initially rejected Company X's claim. The High Court, on appeal, affirmed this, finding that Y's marks ("木林森") were not similar to Company X's registered trademark ("大森林") in terms of appearance, pronunciation, or concept, and therefore, were not similar overall. Company X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Corrective Lens: Emphasizing Concrete Trade Realities in Infringement

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court's reasoning provided a critical framework for analyzing trademark similarity in infringement actions:

1. Reaffirmation of General Principles (with a Twist for Infringement):

The Court began by reiterating the general principles for assessing trademark similarity, explicitly referencing its earlier landmark decision in the Hyozan-jirushi case (Supreme Court, 1968). These principles state that:

- Trademark similarity should be determined based on whether the marks, when used on identical or similar goods, are likely to cause misidentification or confusion as to the source of the goods.

- This determination requires a holistic assessment of the impression, memory, and association that the trademarks convey to traders, considering their appearance, concept (idea/meaning), and pronunciation.

- Furthermore, this assessment should be based on the specific trade circumstances (具体的な取引状況 - gutaitekina torihiki jōkyō), to the extent that such circumstances can be clarified.

Crucially, the Supreme Court added a significant emphasis for the infringement context: "Even if trademarks, observed meticulously, are not similar in appearance, concept, or pronunciation when considered individually, they may become similar depending on the specific trade circumstances. Therefore, the overall similarity (or lack thereof) concerning appearance, concept, and pronunciation can also vary depending on these specific trade circumstances". This highlighted that the real-world context of use could elevate or diminish perceived similarities.

2. Application to "大森林" (Daishinrin) vs. "木林森" (Mokurinshin):

The Court then applied this framework to the specific marks:

- Inherent "Confusing Relationship": The Court noted that the characters "森" (forest/woods, mori/shin) and "林" (woods/grove, hayashi/rin) were common to both marks (though "森" is in X's and Y's, and "林" is also in Y's). The differing initial characters, "大" (Dai - big/great) in X's mark and "木" (Moku/Ki - tree/wood) in Y's mark, could appear visually similar depending on the calligraphy or brushwork. While Y's mark "木林森" was acknowledged as a coined term (造語 - zōgo) without a pre-existing dictionary meaning, both marks, due to their constituent characters (all relating to trees and forests), would evoke an image of trees, woods, or forests, which consumers might associate with hair growth benefits. From this, the Court concluded that, "observed holistically and compared, it is clear that the two are at least in a confusingly related (紛らわしい関係 - magirawashii kankei) state in terms of appearance and concept". This initial finding of an inherent "confusing relationship" was important. The Court stated that, depending on the trade circumstances, "the possibility that consumers might mistake one for the other cannot be denied, and thus there is room to find that they are in a similar relationship".

3. Critique of the High Court's Handling of Trade Circumstances:

The Supreme Court found the High Court's assessment of trade circumstances to be insufficient and flawed:

- Consumer Attentiveness: The High Court had surmised that consumers of hair growth products are typically men strongly desiring hair growth, who would therefore pay close attention to the trademarks on such products and choose carefully. The Supreme Court dismissed this generalization, stating, "it is clear from experience that not all such consumers are necessarily like that".

- Failure to Consider Plaintiff's Actual Use: Company X had specifically alleged that its non-exclusive licensee was using the "大森林" trademark on medicated scalp hair growth lotion and selling it through affiliated companies. The Supreme Court emphasized that the "trade circumstances that could emerge from these alleged facts" also needed to be considered in the similarity assessment.

- Lack of Specific Findings on Defendant's Trade Practices: The High Court had merely stated that even considering conceivable trade situations for X's mark and the actual trade situation for Y's products, the marks were not conceptually similar. However, it failed to make specific findings about crucial aspects of Y's trade, such as:

- How were Y's products sold? Were they sold via door-to-door sales (訪問販売 - hōmon hanbai) or through retail stores (店頭販売 - tentō hanbai)?

- If sold in retail stores, what was the manner of display (展示態様 - tenji taiyō)?

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had made its similarity determination "without concrete findings on such trade circumstances," which constituted either an error in the interpretation and application of the law or insufficient reasoning, clearly affecting the judgment's outcome.

The Supreme Court therefore quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for a more thorough examination of these specific trade circumstances.

"Trade Circumstances": A Different Emphasis in Registration vs. Infringement

The Daishinrin case is particularly significant for highlighting how the consideration of "actual circumstances of trade" differs between the ex parte trademark registration process and inter partes trademark infringement litigation.

- Registration Context (e.g., Hyozan-jirushi, Hodogaya Chemical cases):

- In registration proceedings, the JPO (or a court reviewing a JPO decision) is assessing an applied-for mark (which may not yet be in use) against a prior registered mark (whose owner may or may not be using it, or using it across the full scope of designated goods/services).

- There isn't a concrete "accused infringing mark" in actual use by a defendant.

- Consequently, "trade circumstances" in this context tend to refer to more general, customary, and constant conditions prevailing in the trade of the designated goods or services themselves. The Hodogaya Chemical case, for instance, limited consideration to "general and constant" circumstances for the entire scope of designated goods, excluding an applicant's specific, potentially transient, current uses.

- Infringement Context (e.g., Daishinrin case):

- In infringement lawsuits, the court is faced with a concrete situation: a plaintiff's registered trademark and a defendant's specific "accused mark" that is actually being used in the marketplace in a particular way, on particular goods, through particular channels.

- Therefore, the "specific trade circumstances" that can and must be investigated are much more concrete, detailed, and tied to the actual use of both the plaintiff's mark (if it's in use) and the defendant's accused mark.

- The Daishinrin Supreme Court's insistence on examining details like Company Y's sales methods (door-to-door vs. retail) and product display, as well as the alleged sales activities of Company X's licensee, underscores this deeper, more granular inquiry into marketplace realities that is characteristic of infringement analysis.

The PDF commentary notes that the Daishinrin judgment effectively confirmed that the Hyozan-jirushi principle of considering specific trade circumstances applies to infringement litigation as well, solidifying this approach in Japanese case law. Numerous subsequent court decisions in infringement cases have indeed undertaken detailed examinations of the concrete trade realities surrounding the plaintiff's and defendant's marks.

The Underlying "Confusing Relationship" as a Potential Threshold

An interesting point raised in the commentary is the Supreme Court's initial finding that the marks "大森林" and "木林森," when compared directly, were "at least in a confusingly related state in terms of appearance and concept". The commentary suggests that this preliminary assessment of some inherent "confusing relationship" between the marks themselves might be a necessary prerequisite before a deep dive into trade circumstances becomes the decisive factor. If marks are utterly dissimilar even on a direct comparison of their appearance, concept, and pronunciation, consideration of trade circumstances might not be sufficient to bridge that gap and find similarity. The Supreme Court's explicit finding of this "confusing relationship" may have been a key substantive reason why it ultimately differed from the High Court, which had found them dissimilar even before fully exploring the trade context.

Scholarly Perspectives

The role and weight of "trade circumstances" in assessing trademark similarity remain subjects of academic discussion. Some scholars advocate for a primary focus on the "likelihood of confusion arising from the marks themselves," treating trade circumstances as secondary or clarifying factors. Others argue for a clearer bifurcation, suggesting that the factors and their weightings might differ between assessing similarity for registration purposes versus judging infringement in litigation, given the different policy objectives and available evidence in each scenario.

Conclusion

The Daishinrin (Great Forest) case significantly clarified the importance and nature of considering "actual circumstances of trade" in Japanese trademark infringement litigation. It emphasized that courts must look beyond a mere abstract comparison of marks and delve into the concrete realities of how the plaintiff's registered trademark and the defendant's accused mark are actually used and encountered in the marketplace. By demanding a thorough investigation of specific sales channels, display methods, and other real-world factors, the Supreme Court pushed for a more fact-intensive and context-specific analysis of trademark similarity in infringement disputes. This ensures that legal judgments on infringement are more closely aligned with the actual potential for consumer confusion in the dynamic environment of commerce, distinguishing this approach from the more generalized assessment of trade circumstances typically applied during the trademark registration process.