Trade Secret Litigation in Japan (2024 UCPA Updates): How to Prove Misappropriation and Maximize Damages

Learn how Japan’s 2024 UCPA reforms shift the rules of proof and damages in trade‑secret cases—and what evidence you must prepare to win in court.

TL;DR

Japan’s 2024 revision of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) gives plaintiffs new presumptions and broader damage formulas, but success in court still hinges on meticulous evidence‑building—especially showing how secrets were taken and quantifying lost profits.

Table of Contents

- The Evidentiary Hurdle: Proving Misappropriation

- The Calculation Conundrum: Quantifying Damages

- Litigation Safeguards: Protecting Secrets During Court Procedures

- Conclusion: Preparation is the Best Defense

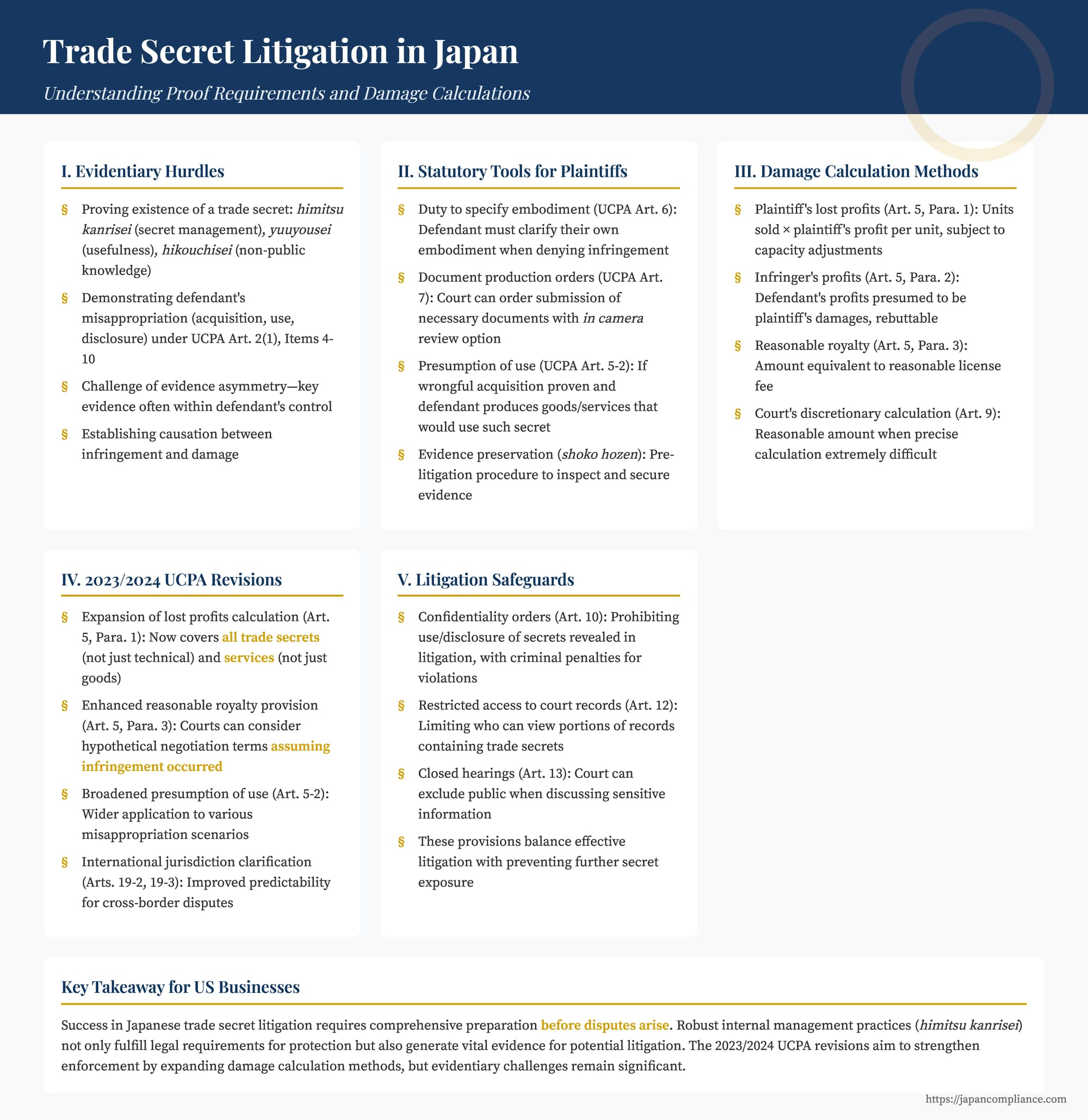

For US businesses, enforcing trade secret rights in Japan is as critical as establishing initial protection. While Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) offers a legal framework for action against misappropriation, litigation presents distinct challenges, particularly concerning the burden of proof and the calculation of damages. Successfully navigating a trade secret lawsuit requires understanding these hurdles and the specific tools available under Japanese law.

This article delves into the key aspects of proving trade secret misappropriation and quantifying harm in Japanese courts, incorporating recent legislative developments aimed at strengthening enforcement.

The Evidentiary Hurdle: Proving Misappropriation

The cornerstone of any trade secret case is proving that actionable misappropriation occurred. The plaintiff (the trade secret holder) bears the burden of establishing several key elements:

- Existence of a Trade Secret: Demonstrating that the information meets the UCPA's three requirements: secret management (秘密管理性 - himitsu kanrisei), usefulness (有用性 - yuuyousei), and non-public knowledge (非公知性 - hikouchisei).

- Defendant's Act of Misappropriation: Proving that the defendant committed one of the prohibited acts under UCPA Article 2, Paragraph 1 (Items 4-10), such as wrongful acquisition, improper use, or unauthorized disclosure.

- Causation and Damages: Linking the defendant's act to the plaintiff's incurred damages (discussed further below).

Common Difficulties:

Proving these elements, especially the defendant's actions, presents significant practical difficulties:

- Evidence Asymmetry: Crucial evidence demonstrating misappropriation (e.g., internal use of the secret, communication logs showing disclosure) often resides exclusively within the defendant's control. Japan's civil procedure system lacks the broad pre-trial discovery mechanisms familiar in the US, making it harder for plaintiffs to compel the production of incriminating evidence held by the opposing party.

- Secrecy of Infringing Acts: Misappropriation, particularly internal use of manufacturing processes or strategic plans, often occurs behind closed doors, leaving little direct external evidence.

Statutory Tools and Strategies for Plaintiffs:

Despite these challenges, the UCPA and related procedures offer some tools, although their effectiveness varies:

- Leveraging Internal Management Records: As highlighted in our previous guide, robust internal himitsu kanrisei measures are not just crucial for establishing a trade secret exists, but also for proving misappropriation. Access logs showing unusual activity by a departing employee, markings on documents found in a defendant's possession, and signed NDAs can provide vital circumstantial evidence. Meticulous record-keeping is essential groundwork for potential litigation.

- Duty to Specify Embodiment (UCPA Art. 6 - 具体的態様の明示義務): If a plaintiff alleges infringement (e.g., "You are using my secret manufacturing process X"), and the defendant denies it, Article 6 requires the defendant to specifically clarify their own process or product embodiment they are actually using. This aims to prevent simple denials and push the defendant to provide concrete information, helping to clarify the dispute. However, its impact is limited: there's no direct penalty for non-compliance beyond potentially influencing the judge's view of the facts, and defendants can refuse if they have "reasonable grounds" (相当の理由 - soutou no riyuu), such as their own process being a trade secret (though the availability of confidentiality orders, discussed below, might weaken this excuse).

- Document Production Orders (UCPA Art. 7 - 書類の提出等): Courts have the authority, upon a party's motion, to order the possessor of documents (typically the defendant) to submit materials necessary for proving infringement or calculating damages. This applies to a broader range of documents than standard civil procedure rules might otherwise compel.

- Limitations: The document holder can refuse if there is a "legitimate reason" (正当な理由 - seitou na riyuu). While the existence of confidentiality orders (Art. 10) might make refusal based solely on the documents containing trade secrets less justifiable, refusal is still possible. Courts weigh the necessity for proof against the potential harm of disclosure. If an order is violated, the court may accept the requesting party's assertions about the document's contents as true.

- In Camera Inspection: To balance the need for evidence with confidentiality, Article 7 allows the court to require the document holder to present the documents privately (in camera) to the judge, who can then decide on the necessity of production without disclosing the contents to the requesting party initially. The court may show the documents to the parties later, often under a protective order.

- Presumption of Use (UCPA Art. 5-2 - 使用等の推定): Introduced in 2015 and significantly expanded by the 2023 revision (effective April 2024), this provision aims to ease the burden of proving the defendant's use of a trade secret.

- Conditions: If the plaintiff proves that (a) the defendant wrongfully acquired a trade secret (or acquired it under specific circumstances knowing of prior wrongdoing), AND (b) the defendant is subsequently producing goods, providing services, or engaging in business activities that would typically result from using such a secret, then the defendant is presumed to have used the trade secret in that activity.

- Scope Expansion (2023/2024): Originally, this presumption applied mainly to technical secrets (like production methods) and specific types of wrongful acquisition. The revision broadened its potential application to cover a wider array of acquisition scenarios, including situations where the secret was obtained legitimately but later misused with culpable knowledge (falling under Art. 2(1) Items 7 & 9).

- Impact & Limitations: Plaintiffs still need to prove the initial wrongful acquisition (or equivalent culpable state of mind). Historically, Article 5-2 was rarely invoked, partly due to the difficulty in proving the prerequisite acquisition. Whether the 2023/2024 expansion makes it a more potent tool remains to be seen. The defendant can still rebut the presumption by proving they developed the process/product independently or used different information.

- Evidence Preservation (証拠保全 - Shoko Hozen): While not part of the UCPA itself, this pre-litigation procedure under the Code of Civil Procedure allows a party anticipating litigation to ask the court to inspect and preserve evidence (e.g., inspecting a defendant's factory or seizing documents) before a lawsuit is filed, preventing its destruction or alteration. This requires showing a need for preservation and can be a powerful, albeit exceptional, tool.

The Calculation Conundrum: Quantifying Damages

Even if misappropriation is proven, quantifying the resulting financial harm is another major challenge in Japanese trade secret litigation. Establishing a clear causal link between the infringement and the monetary loss, and calculating that loss precisely, can be complex. The UCPA provides specific statutory methods to aid this process (Article 5).

Statutory Methods for Damage Calculation (UCPA Art. 5):

Plaintiffs can choose the most advantageous calculation method based on the available evidence.

- Plaintiff's Lost Profits (Art. 5, Para. 1 - 逸失利益):

- Calculation: Damages are calculated as the number of units of infringing goods sold (or volume of infringing services provided) by the defendant multiplied by the plaintiff's profit per unit (or per service transaction).

- Scope Expansion (2023/2024): A crucial change effective April 2024 significantly expanded this provision. Previously limited mainly to technical secrets embodied in goods, it now applies to all types of trade secrets (including business information like customer lists) and covers situations where the infringer provides services using the secret.

- Limitations/Deductions: The calculated amount may be reduced if the defendant proves that factors other than the infringement contributed to the plaintiff's inability to sell (e.g., plaintiff's limited production/sales capacity, market competition, defendant's own marketing efforts). However, the 2023/2024 revision added a provision (mirroring patent law) allowing the plaintiff to claim a reasonable royalty for sales exceeding their own capacity.

- Infringer's Profits (Art. 5, Para. 2 - 侵害者利益):

- Presumption: The profits gained by the defendant through the act of infringement are presumed to be the amount of the plaintiff's damages.

- Challenges: The primary difficulty lies in obtaining accurate data on the defendant's profits attributable to the infringement. Even if obtained, the defendant can rebut the presumption by demonstrating that their profits were due to factors other than the use of the trade secret (e.g., their own technology, brand value, or business efforts) or that there was no causal link to the plaintiff's loss.

- Reasonable Royalty (Art. 5, Para. 3 - 相当実施料額):

- Calculation: The plaintiff can claim an amount equivalent to what they would have been entitled to receive as a reasonable royalty for the use of the trade secret. This often serves as a minimum damages floor.

- Determining the Royalty: Calculating a "reasonable" royalty involves considering factors like industry licensing practices, the nature and value of the secret, and the terms of comparable licenses (if any exist).

- 2023/2024 Clarification: The revision clarified that when calculating this amount, the court can consider the terms that would likely have been agreed upon in a hypothetical license negotiation conducted with the knowledge that infringement had occurred. This acknowledges that a license negotiated post-infringement might command a higher rate than a standard pre-use license, potentially leading to increased damage awards under this provision.

Court's Discretionary Calculation (UCPA Art. 9 - 相当な損害額の認定):

If proving the precise amount of damages is extremely difficult due to the nature of the facts, even using the Article 5 presumptions, Article 9 allows the court to determine a "reasonable amount" of damages based on the overall arguments and evidence presented during the litigation.

Addressing Practical Issues in Damages:

- The "Embodiment" (Katai) Issue: Some past lower court decisions showed reluctance to apply Article 5 damage calculations, particularly Paragraph 1, if the trade secret (e.g., customer data) wasn't directly "embodied" (化体 - katai) in the product sold by the infringer. The 2023/2024 expansion of Article 5, Paragraph 1 to cover services and non-technical secrets may help mitigate this restrictive interpretation.

- Adequacy of Awards: There's a perception that damage awards in Japanese IP cases, including trade secrets, tend to be lower than those in the US. The recent legislative efforts, particularly the 2023/2024 UCPA revisions regarding damages, reflect an intent to enable courts to award more substantial and adequate compensation for trade secret misappropriation.

Litigation Safeguards: Protecting Secrets During Court Procedures

Recognizing that litigation itself can risk further exposure of confidential information, the UCPA includes safeguards:

- Confidentiality Orders (Art. 10 - 秘密保持命令): Courts can issue orders prohibiting parties, their lawyers, or others involved in the litigation from using trade secrets disclosed during the proceedings for any purpose other than the litigation itself, or from disclosing them to unauthorized individuals. Violations are subject to criminal penalties.

- Restricted Access to Court Records (Art. 12 - 閲覧等の制限): Parties can request the court to restrict access to parts of the court record containing trade secrets, limiting viewing primarily to the involved parties and their legal counsel.

- Closed Hearings (Art. 13 - 公開停止): The court can decide to close parts of hearings to the public when sensitive trade secret information is discussed during witness examinations or party questioning.

Conclusion: Preparation is the Best Defense

Litigating trade secret cases in Japan involves navigating significant hurdles in proving both the act of misappropriation and the resulting damages. While the Unfair Competition Prevention Act provides essential tools, including document production orders, presumptions of use and damages, and procedural safeguards, success is not guaranteed. The recent 2023/2024 revisions aim to strengthen enforcement by expanding damage calculation methods and the presumption of use, but the practical impact remains to be fully realized.

For US businesses, the most effective strategy begins long before any dispute arises. Implementing comprehensive, well-documented trade secret management practices not only fulfills the crucial himitsu kanrisei requirement for protection but also generates the internal records and evidence that can be vital should litigation become necessary. Understanding the challenges and available tools within the Japanese legal system allows companies to better prepare for enforcing their valuable trade secret rights.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Outline of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act – Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry

- Unfair Competition Prevention Act (English translation) – Japanese Law Translation Database