Towing the Line: A 1975 Japanese Supreme Court Case on "Increase of Risk" in Marine Hull Insurance

Judgment Date: January 31, 1975

Court: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench

Case Name: Insurance Claim Case

Case Number: Showa 44 (O) No. 718 of 1969

Introduction: The Perils of Unforeseen Changes in Maritime Voyages

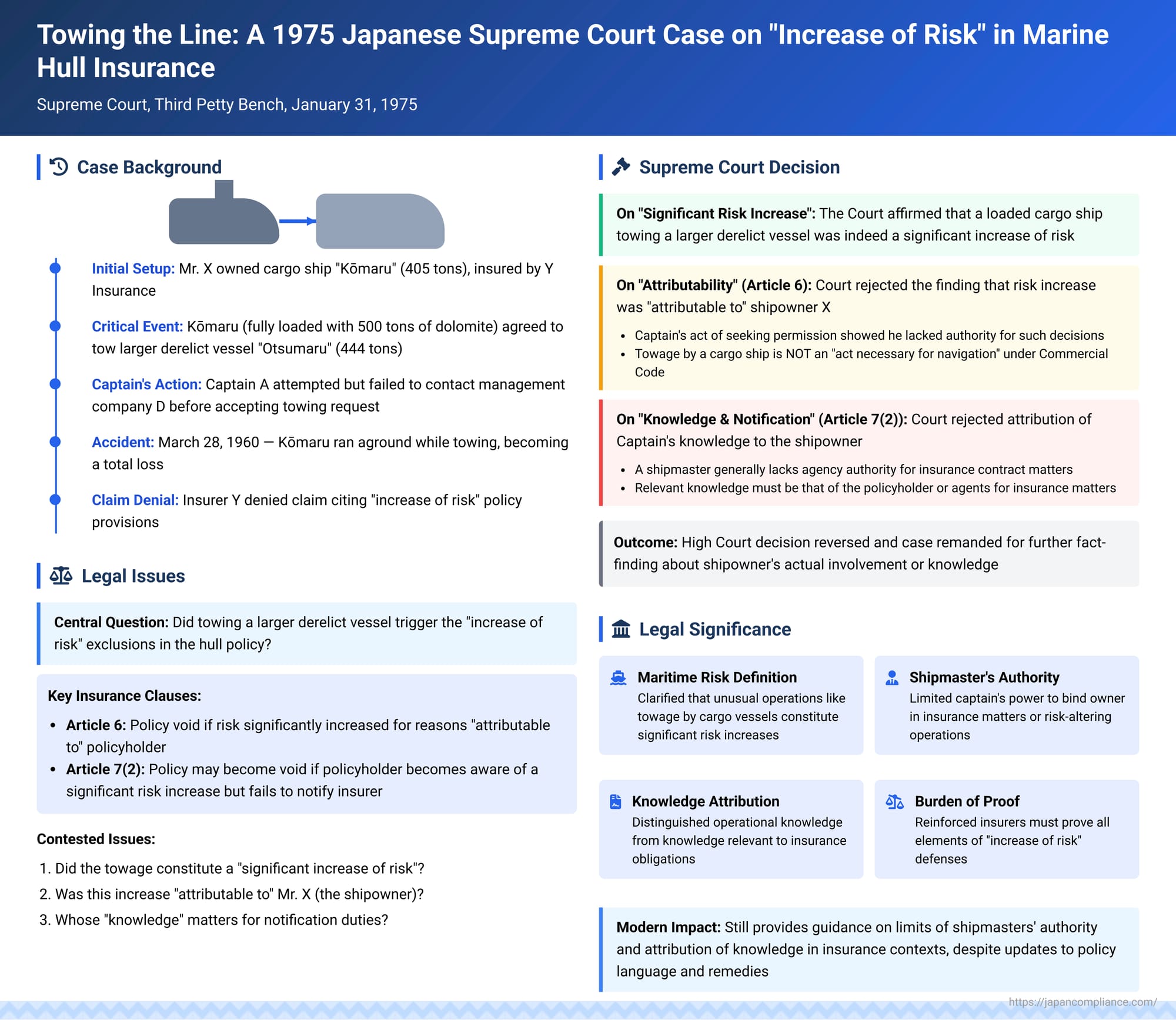

Marine hull insurance provides crucial financial protection for shipowners against loss or damage to their vessels. A fundamental principle underpinning these insurance contracts is the concept of "increase of risk" (危険の著増 - kiken no chōzō). If, after the insurance policy has been put in place, the nature or extent of the risk insured significantly changes or increases, particularly due to actions taken by or known to the insured, the coverage provided by the policy can be seriously affected, potentially even leading to the policy being voided by the insurer.

But what constitutes a "significant increase of risk" in the often unpredictable world of maritime operations? For instance, if a cargo ship, primarily designed and insured for carrying goods, undertakes the unscheduled and potentially hazardous task of towing another disabled vessel, does this action trigger the "increase of risk" provisions in its hull insurance policy? And if it does, under what circumstances can this increased risk be considered "attributable to the policyholder or insured," or when would the insured's knowledge of such a change (and a subsequent failure to notify the insurer) lead to a loss of coverage? These complex questions, involving the interplay of maritime practice, agency law, and insurance contract interpretation, were at the forefront of a key 1975 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Factual Backdrop: A Loaded Cargo Ship, an Unscheduled Tow, and a Total Loss

The case involved Mr. X, the owner of a steamship named "Kōmaru." The Kōmaru, a general cargo vessel of approximately 405 gross tons, was insured under a marine hull insurance policy with Y Insurance Company.

The policy contained standard clauses common in marine insurance regarding "increase of risk":

- Article 6: This clause stipulated that if the risk insured under the policy was significantly changed or increased during the policy period due to reasons "attributable to the policyholder or the insured," the insurance contract would become void, unless the insurer had given prior written consent to such change or increase.

- Article 7, Paragraph 2: This clause addressed situations where a significant increase of risk occurred due to reasons not directly attributable to the policyholder or insured. It provided that if the policyholder or insured became aware of such a significant change or increase in risk, they had a duty to promptly notify the insurer in writing. If they failed to provide this notification, the insurer could deem the policy to have become void from the time the risk had changed or increased.

The Kōmaru was loaded with a cargo of 500 tons of dolomite at Kawasaki port. While in this loaded condition, an unusual task arose. Captain A, the master of the Kōmaru, was requested by an agent of B Shipping (the company that had time-chartered the Kōmaru) to tow another vessel, the "Otsumaru." The Otsumaru was a larger ship (approximately 444 gross tons), unpowered, unrepaired, and essentially a derelict. The request was for the Kōmaru to tow the Otsumaru from Kawasaki to Imabari in Ehime Prefecture.

Before agreeing to this towage, Captain A attempted to contact D Steamship Company, the entity that managed the Kōmaru's operations on behalf of the owner, Mr. X, to obtain approval. However, the representative of D Steamship Company was reportedly absent, and Captain A was unable to secure clear and explicit consent for the towage operation. Nevertheless, believing that the shipowner, Mr. X, would ultimately approve or understand the necessity of the action, Captain A decided to accept the towage request.

Subsequently, while the Kōmaru was on its voyage, laden with its cargo of dolomite and now also towing the derelict Otsumaru, it ran aground on a reef off Omaezaki in Shizuoka Prefecture on March 28, 1960. The Kōmaru was so severely damaged that it became a total loss.

Mr. X, the shipowner, then filed a claim with Y Insurance Company under the hull insurance policy for the loss of the Kōmaru. Y Insurance Company denied the claim, primarily invoking the "increase of risk" clauses (Articles 6 and 7(2)) in the policy. The insurer argued that the act of towing the Otsumaru, especially while the Kōmaru was already loaded with cargo, constituted a significant increase in the insured risk, which either voided the policy or entitled the insurer to deem it void due to lack of notification.

The Core Legal Issues Before the Courts

The ensuing legal battle focused on several key questions:

- Did the act of the Kōmaru, a loaded cargo ship, undertaking the towage of the larger, unpowered, and derelict Otsumaru, constitute a "significant increase of risk" within the meaning of the insurance policy?

- If it did, was this increase in risk "attributable to" Mr. X (the shipowner and insured) for the purposes of triggering Article 6 of the policy (which could void the contract)? This question hinged significantly on whether Captain A, the shipmaster, had the authority to commit the vessel to such a towage contract in a way that would bind the owner for insurance purposes.

- Alternatively, if the increase in risk was not deemed directly "attributable to" Mr. X, did Mr. X (or any agent whose knowledge could be properly imputed to him for insurance matters) have "knowledge" of this significant risk increase? And if so, did a failure to promptly notify Y Insurance Company allow the insurer to deem the policy void under Article 7, Paragraph 2? This involved determining whose knowledge is relevant for such notification duties under a marine insurance contract.

The Lower Court's Findings (High Court)

The High Court (the appellate court whose decision was appealed to the Supreme Court) had ruled in favor of Y Insurance Company, dismissing Mr. X's claim. Its key findings were:

- It determined that the Kōmaru being heavily loaded (to the point where its midship freeboard was only 0.5 meters) was, in itself, a significant increase of risk.

- It also found, more critically, that the act of this loaded cargo ship then undertaking the towage of the Otsumaru (a larger, unpowered, and unrepaired derelict vessel) constituted a further, very significant increase of risk, and that this towing operation was a major contributing cause of the Kōmaru's eventual grounding and loss.

- The High Court inferred that Captain A either possessed the authority (delegated from Mr. X through D Steamship Company) to enter into such a towage contract, or at least that Mr. X had given his tacit approval for this specific towage. Based on this, it concluded that the increase of risk due to the towage was "attributable to" Mr. X, thereby triggering the policy-voiding provision of Article 6.

- The High Court also suggested, in the alternative, that even if the risk increase was not directly attributable to Mr. X, the policy would still be voided under Article 7, Paragraph 2, due to a failure to notify the insurer of the risk increase, implying that Captain A's knowledge of the towage was sufficient to trigger this duty for Mr. X.

The Supreme Court's Decision (January 31, 1975): Reversing on Attributability and Knowledge, Remanding for Further Facts

The Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, carefully reviewed the High Court's decision and found significant errors in its legal reasoning and factual inferences concerning the attributability of the risk increase and the shipowner's knowledge. The Supreme Court, therefore, reversed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings.

Affirmation of "Significant Increase of Risk" due to Towage

The Supreme Court began by addressing the High Court's finding that the towage operation itself constituted a significant increase of risk. The Supreme Court agreed with this part of the High Court's assessment, stating that the High Court's determination that the Kōmaru towing the Otsumaru was a significant increase of risk, and a major cause of the grounding, was sustainable based on the evidence presented. (The Supreme Court noted that since this finding on towage was sufficient to establish a significant risk increase, it did not need to definitively rule on whether the Kōmaru's alleged overloading, prior to the towage, would also have constituted such an increase on its own).

Rejection of the Finding that the Risk Increase was "Attributable to the Policyholder/Insured" (for Article 6 purposes)

The Supreme Court then turned to the crucial issue of whether this significant increase in risk was "attributable to" Mr. X, the shipowner and insured, as required by Article 6 of the policy for the policy to become void on that ground. The Court found the High Court's reasoning on this point to be flawed:

- Captain's Authority to Contract for Towage: The Supreme Court focused on the fact that Captain A had specifically telephoned D Steamship Company (Mr. X's operational managers) seeking consent before undertaking the towage. The Court reasoned that this very act strongly suggested that Captain A himself did not believe he possessed the inherent authority to enter into such an unusual and risky towage contract on his own initiative and bind the shipowner. The High Court's inference that Captain A did have such authority, or that Mr. X had given some form of tacit approval through D Steamship Company, was deemed by the Supreme Court to be either a factual finding made without sufficient supporting evidence or the result of a flawed deductive reasoning process.

- Shipmaster's Statutory Powers (under the former Commercial Code Article 713, Paragraph 1): The High Court had also cited the general statutory powers granted to a shipmaster under the Commercial Code (Article 713, Paragraph 1, which is now Article 708, Paragraph 1 of the current Code) to perform acts "necessary for navigation" when the vessel is outside its home port. The High Court had suggested this might provide a basis for Captain A's authority to undertake the towage. However, the Supreme Court disagreed with this application of the law. It ruled that a cargo ship, already laden with its own cargo, undertaking the towage of another vessel (an act that significantly endangers the towing ship itself) is generally not considered an "act necessary for navigation" within the meaning of this statutory provision, unless there are very specific and special circumstances that might justify it (which the High Court had not found to exist in this case). Thus, the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court had misapplied this statutory provision in trying to find a basis for Captain A's authority.

Because the Supreme Court found the High Court's basis for determining that the risk increase was "attributable to" Mr. X to be legally and factually unsupported, it concluded that Article 6 of the policy (voiding the contract for an attributable increase in risk) could not be applied based on the existing findings.

Rejection of Policy Voidance under Article 7, Paragraph 2 (Knowledge of Risk Increase and Failure to Notify)

The Supreme Court then addressed the High Court's alternative reasoning for voiding the policy – that even if the risk increase was not directly attributable to Mr. X, the policy was nevertheless voided under Article 7, Paragraph 2, due to a failure by Mr. X to notify Y Insurance Company of a known risk increase. The Supreme Court found this part of the High Court's judgment also to be legally flawed:

- Whose Knowledge is Relevant for Insurance Notification Duties?: Article 7, Paragraph 2, requires that the "policyholder or the insured" must have known of the significant increase in risk and then failed to notify the insurer. The High Court appeared to have operated on the premise that Captain A's knowledge of the towage operation (and its inherent risks) could be imputed to Mr. X, the shipowner, for the purposes of this clause.

- The Supreme Court decisively disagreed with this imputation. It held that while a shipmaster is, of course, responsible for the navigational and operational aspects of the vessel under their command, they generally do not possess agency authority with respect to the ship's insurance contract matters.

- Therefore, for the purpose of determining whether the policyholder or insured "knew" of a significant risk increase under marine insurance policy terms like Article 7, Paragraph 2 (which triggers a duty to notify the insurer), that knowledge must be assessed based on what was known by the policyholder themselves (Mr. X), the specifically named insured, or their duly authorized agents for insurance-related matters. The shipmaster's operational knowledge of changes in the voyage or the vessel's use does not automatically and invariably translate into the legal "knowledge" of the shipowner for the purpose of triggering duties under the insurance contract's risk increase notification clauses.

- Since the High Court had not made any specific finding that Mr. X himself (or his relevant agents for insurance purposes, like D Steamship Company in its capacity as manager of insurance affairs) had actual knowledge of the towage and the resultant significant increase in risk (relying instead on what appeared to be an improper imputation of Captain A's knowledge), its conclusion that Article 7, Paragraph 2, applied to void the policy was based on an erroneous interpretation and application of that clause.

Outcome of the Supreme Court Appeal

Because the Supreme Court found that the High Court's findings on both the "attributability" of the risk increase (for Article 6) and the "knowledge and notification" requirement (for Article 7, Paragraph 2) were legally flawed and not supported by proper reasoning or sufficient findings of fact related to the shipowner himself (or his proper agents for insurance), it concluded that the High Court's judgment dismissing Mr. X's claim could not stand. The Supreme Court, therefore, reversed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings. This would require the High Court to re-examine the facts, particularly concerning Mr. X's actual or properly attributable knowledge and involvement (or lack thereof) in the decision to undertake the towage operation, before it could correctly apply the increase of risk clauses in the insurance policy.

Analysis and Implications of the Ruling

The 1975 Supreme Court of Japan decision in this marine hull insurance case provided critical interpretations of "increase of risk" clauses that have had lasting significance.

1. Defining "Significant Increase of Risk" in Maritime Operations:

The judgment, by affirming the High Court's finding on this specific point, reinforces that certain deviations from a vessel's normal or intended use, such as a fully laden cargo ship undertaking the towage of a larger, disabled, and unrepaired vessel, can indeed be considered a "significant increase of risk" within the meaning of standard marine hull insurance policies. This aligns with general maritime industry understanding that towage operations, especially by vessels not designed as tugs, inherently involve greater hazards.

2. Clarifying the Limits of a Shipmaster's Authority – Particularly in Relation to Insurance Contracts:

This case is particularly important for its clear delineation of the limits of a shipmaster's authority.

- While a shipmaster has broad powers regarding the day-to-day navigation and operational management of the vessel, especially when away from the home port (as recognized in provisions like the former Commercial Code Article 713(1)), their authority does not typically extend to unilaterally entering into contracts or undertaking operations that are abnormal for the vessel's designated use and which materially alter the risks insured under the owner's hull policy, unless they have specific authorization from the owner or their designated operational managers. The act of a cargo ship committing to a salvage-like towage operation was seen by the Supreme Court as falling outside such inherent navigational authority.

- More critically for insurance law, the Supreme Court established that a shipmaster's knowledge of operational changes or increased risks is not automatically imputed to the shipowner for the purposes of fulfilling the shipowner's distinct contractual duties under an insurance policy, such as the duty to notify the insurer of a material change in risk as required by clauses like Article 7, Paragraph 2. The Court recognized that the agency relationship for insurance matters (which might involve the owner directly, or their office-based managers or insurance brokers) is separate and distinct from the shipmaster's command and operational responsibilities at sea. This distinction is vital for shipowners in understanding and managing their insurance obligations.

3. A Stricter Standard for "Attributable to the Policyholder/Insured":

The Supreme Court's reluctance to easily find that the towage operation was "attributable to" the shipowner (Mr. X) without clear proof of Mr. X's (or his proper agent's for such decisions) consent or authorization indicates a relatively strict interpretation of this crucial phrase in policy exclusion clauses. The mere fact that the shipmaster (who is, in a general sense, an employee or agent for navigational purposes) took an action that increased risk does not automatically make that increase "attributable" to the shipowner for the purpose of voiding the insurance policy, especially if the master acted outside the scope of their proper authority for making such a risk-altering contractual commitment or operational decision.

4. Reinforcing the Insurer's Burden of Proof for "Increase of Risk" Defenses:

The judgment implicitly reinforces the principle that the insurer bears the legal burden of proving all the necessary elements of its defenses when it relies on "increase of risk" clauses to deny a claim. If the insurer alleges that the increase was "attributable to" the insured, it must provide sufficient evidence to establish the insured's involvement, authorization, or culpable failure to prevent. If the insurer alleges a failure to notify of a known risk increase, it must prove that the insured (or their relevant agent for insurance matters) actually knew of the specific increase in risk and then failed in their duty to notify.

5. Practical Guidance for Shipowners, Their Managers, and Insurers:

- This case highlights the critical importance for shipowners to have clear lines of communication and clearly defined levels of authority with their shipmasters and any operational managers (like D Steamship Company in this case) regarding any proposed deviations from a planned voyage or the undertaking of unusual or high-risk operations such as unscheduled towage. Such decisions have profound insurance implications.

- Insurers, when investigating claims where an increase of risk might be a factor, must direct their inquiries carefully to ascertain the knowledge and actions not just of the shipmaster during the voyage, but, more importantly, of the policyholder (the shipowner) or their specifically designated agents responsible for managing insurance matters and contractual commitments.

6. The Context of Older Policy Clauses and Potential Differences in Modern Policies:

It is worth noting, as the legal commentary accompanying this case points out, that this 1975 decision was interpreting standard hull insurance clauses that dated back to a 1933 version. Under those older clauses, the primary consequence of a proven breach of these "increase of risk" provisions was often the "voiding" or "lapsing" of the entire insurance policy, either from the outset or from the time the risk increased. Modern insurance policies, particularly those drafted under the influence of later legal developments such as Japan's comprehensive Insurance Act of 2008, might frame the consequences of an unnotified or unagreed increase of risk differently. For example, instead of the entire policy becoming void, the insurer might be entitled to be exempt from paying for a loss that was proximately caused by the unnotified increase of risk, or the policy terms might allow for an adjustment of premiums, or in some cases, the insurer might have a right to terminate the contract for the future. However, despite these potential differences in the remedial consequences, the core principles established by this Supreme Court case regarding what constitutes a significant increase of risk in maritime operations, the recognized limits of a shipmaster's authority to bind the shipowner in ways that materially increase insured risk, and whose knowledge is deemed relevant for the purposes of the insured's notification duties, likely continue to hold considerable persuasive value and inform the interpretation of similar concepts in contemporary marine insurance law.

Conclusion

The January 31, 1975, Supreme Court of Japan decision provided crucial and lasting interpretations of "increase of risk" clauses commonly found in marine hull insurance policies. The Court affirmed that an unusual and inherently hazardous operation, such as a fully loaded cargo ship undertaking the towage of a larger, disabled, and unrepaired vessel, indeed constitutes a "significant increase of risk" within the meaning of such policies.

More importantly, however, the Supreme Court clarified two vital points regarding the application of these clauses:

- For such an increase in risk to be deemed "attributable to" the shipowner (which could lead to the policy being voided under one type of common clause), there must be clear evidence that the shipowner, or their duly authorized operational or contractual agents, consented to or authorized the risk-increasing activity. The shipmaster, acting alone and potentially outside the scope of their proper authority for such extraordinary decisions, does not automatically bind the owner in this regard.

- For policy clauses that require the insured to notify the insurer of any known significant increase in risk (with failure to do so potentially allowing the insurer to deem the policy void), the "knowledge" in question is specifically that of the shipowner (the policyholder or named insured) or their designated agents responsible for managing insurance matters. The operational knowledge of the shipmaster concerning changes in the voyage or the vessel's use is not automatically imputed to the shipowner for the purpose of triggering these contractual notification duties under the insurance policy.

This landmark ruling carefully delineated the distinct spheres of authority and knowledge that exist between a ship's operational command (the master) and the contractual rights and responsibilities of the shipowner under their marine insurance policy. It established important precedents for how "increase of risk" provisions are to be interpreted and applied, emphasizing the need for clear proof of the shipowner's involvement or relevant knowledge before coverage can be denied on these grounds.