Tortious Acquisition of a Judgment and Res Judicata: Seeking Damages After a Deceptively Obtained Ruling

Judgment Date: July 8, 1969 (Third Petty Bench, Supreme Court of Japan)

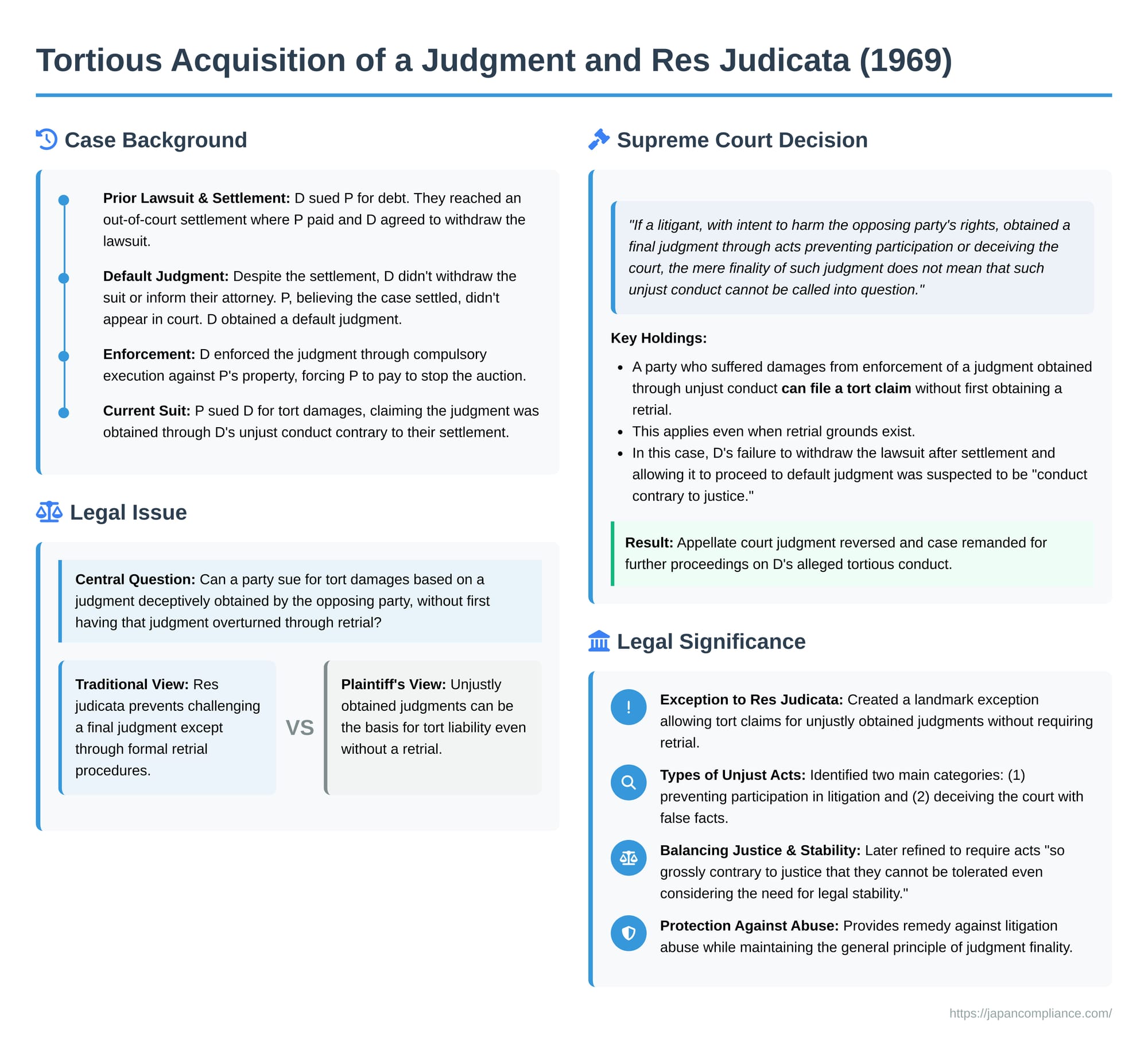

This 1969 Japanese Supreme Court decision addresses a critical issue: can a party who suffered damages due to the enforcement of a final judgment, which was allegedly obtained through the opposing party's fraudulent or unjust conduct during the litigation process, sue for tort damages without first having that prior judgment overturned through a retrial (再審 - saishin)? The Court held that, under certain egregious circumstances, such a tort claim for damages is permissible even if the prior judgment remains formally in effect and even if grounds for a retrial exist.

Case Background: A Settlement Broken, a Default Judgment, and Subsequent Enforcement

The facts of the case, as alleged by the appellant (plaintiff in the current suit, hereinafter "P"), are as follows:

- The Prior Lawsuit (Zen-so) and Out-of-Court Settlement: The appellee (defendant in the current suit, hereinafter "D") had previously filed a lawsuit against P for outstanding loans and sales proceeds (the "Prior Suit").

- During the pendency of the Prior Suit, P and D reached an out-of-court settlement. P agreed to pay a settlement amount, and in return, D agreed to partially forgive the remaining debt and, crucially, to withdraw the Prior Suit. P duly paid the settlement amount.

- D's Failure to Withdraw the Prior Suit and Default Judgment: Despite the settlement and P's payment, D failed to withdraw the Prior Suit. D also allegedly did not inform D's own litigation representative (attorney) about the settlement.

- Consequently, when the first oral hearing date for the Prior Suit arrived, P, believing the matter settled and the suit to be withdrawn, did not appear.

- The court, with P absent, proceeded with the hearing and rendered a default judgment in favor of D, based on D's original claims (which should have been extinguished or withdrawn by the settlement).

- P's Inaction and Judgment Finalization: P, after being served with the default judgment, contacted D (through an intermediary) requesting D to withdraw the suit as promised. D's husband reportedly assured P not to worry. Relying on this, P did not file an appeal, and the default judgment became final and binding.

- Enforcement and P's Initial Counter-Actions: D subsequently initiated compulsory execution against P's real property based on this final default judgment.

- P then filed a suit for a declaration of non-existence of the debt and an action to oppose execution (請求異議の訴え - seikyū igi no uttae), obtaining a temporary stay of execution.

- However, the first instance court in these counter-actions dismissed P's claims, reasoning that the prior default judgment was validly finalized and its res judicata effect prevented P from denying the existence of the debt unless the judgment was overturned through a retrial. The stay of execution was lifted, and the compulsory auction proceeded.

- The Current Lawsuit (Hon-so) for Damages: P paid the amount demanded under the prior judgment to D to have the compulsory auction withdrawn. P then appealed the dismissal of the action to oppose execution and, in the appellate court, amended the claim to one for tort damages against D. P alleged that D, through intentional or negligent wrongful acts (obtaining a default judgment in breach of the settlement agreement and then enforcing it), caused P to suffer damages (the amount P was forced to pay).

- Appellate Court Ruling in the Current Lawsuit: The appellate court dismissed P's claim for damages. It reasoned that the prior default judgment was validly finalized. Therefore, due to its res judicata effect, P could not assert the non-existence of the claim established by that judgment. Unless the prior judgment was overturned through a retrial, the compulsory execution based on it could not be deemed unlawful. Thus, P's tort claim, which presupposed the unlawfulness of the execution, was unfounded. P appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment and Reasoning

The Supreme Court overturned the appellate court's decision and remanded the case to the Fukuoka High Court for further proceedings.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- General Effect of Res Judicata: When a judgment becomes final and binding, its res judicata effect establishes the existence of the claim adjudicated therein, and enforceability arises according to its content. This is undeniable.

- Exception for Unjustly Obtained Judgments:

- However, if, in the process of the judgment's formation, a litigant, with the intent to harm the opposing party's rights, through acts or omissions, prevented the opposing party from participating in the court proceedings, or deceived the court by asserting false facts, etc., and as a result, obtained a final judgment with content that should not have originally been possible, and then executed it – the mere finality of such a judgment does not immediately mean that such unjust conduct by the party cannot be called into question.

- The party who suffered damage due to such conduct should not be precluded from seeking compensation for damages through an independent tort action, even if the conduct also constitutes grounds for a retrial of the prior judgment and a separate retrial action could be filed.

- Application to the Current Case:

- The appellate court found that D had entered into an out-of-court settlement with P to partially forgive the debt and withdraw the Prior Suit, and had received payment according to this settlement. However, D breached the obligation to withdraw the suit and did not inform D's own attorney of these facts. As a result, the Prior Suit proceeded to a default judgment in D's favor in P's absence.

- P did not attend the oral hearing in the Prior Suit because P believed, due to the settlement and D's promise to withdraw, that there was no longer a need to continue with the court proceedings. P also did not appeal after receiving the judgment for the same reason.

- It can be inferred that if P had known D truly intended to pursue the claim to judgment, P would have appeared in court, raised the settlement as a defense, prevented a judgment against P, or at least appealed if P had lost.

- The appellate court had also found D's subsequent claim that the settlement was rescinded due to fraud by P to be unconvincing.

- Therefore, even if D did not engage in active fraudulent acts to prevent P's participation after the settlement, it is suspected that D, taking advantage of P's reliance on the settlement and P's consequent inaction in the litigation, allowed D's attorney to continue the proceedings and obtain the final judgment.

- Since the content of that judgment was to uphold a claim that had been extinguished by the settlement, D should not have proceeded with compulsory execution based on this judgment.

- In this case, there is a suspicion that D engaged in conduct contrary to justice in obtaining and executing the said final judgment.

- Error of the Appellate Court:

- The appellate court, by dismissing P's tort claim solely based on the res judicata of the prior judgment without fully examining these circumstances, erred in its interpretation of the law and failed to conduct a sufficient trial, resulting in defective reasoning. This error clearly affected the outcome.

The Supreme Court therefore quashed the appellate judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings on the issue of D's alleged tortious conduct.

Significance and Commentary (Drawing from the Provided PDF - ms81.pdf)

This 1969 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling that carves out an important exception to the normally preclusive effect of res judicata. It establishes that a party who has suffered damages due to a judgment obtained through the opponent's fraudulent or unjust conduct during the litigation process may, under certain circumstances, sue for tort damages without first needing to have the prior judgment annulled through a retrial.

Key aspects highlighted by the PDF commentary:

- The General Preclusive Effect of Res Judicata: Ordinarily, a final judgment conclusively determines the rights and obligations between the parties regarding the subject matter of the litigation. A party cannot typically bring a new lawsuit that would contradict these established rights. ([Source 1])

- A tort claim alleging that a prior judgment was wrongly obtained and caused damage would usually be seen as conflicting with the res judicata of that prior judgment, because it implicitly challenges the validity of the claim upheld in the prior suit. ([Source 1])

- Exception for "Tortious Acquisition of Judgment": This decision establishes that if a final judgment was obtained through "unjust acts" (不正な行為 - fusei na kōi) by one party that are "contrary to justice" (正義に反する - seigi ni hansuru), the wronged party can sue for damages in tort, even if the prior judgment remains formally in effect and even if retrial is an available remedy. ([Source 1] - Main holding of the Supreme Court)

- The Court identified two main categories of such "unjust acts":

- (a) Preventing Participation: Acts or omissions, done with intent to harm the opponent's rights, that prevent the opponent from participating in the litigation process.

- (b) Deceiving the Court: Asserting false facts to deceive the court.

- If such conduct leads to a judgment that would not otherwise have been possible, and that judgment is enforced, a tort claim for damages is permissible.

- The Court identified two main categories of such "unjust acts":

- Evolution of Case Law:

- The PDF commentary notes that a prior Supreme Court case (1965) had already hinted at the possibility of a tort claim for a judgment obtained through collusion, even while stating that the usual remedy is retrial. ([Source 2])

- This 1969 decision firms up this exception.

- However, subsequent Supreme Court cases (e.g., a 1998 decision, Case 37(2) in the Hyakusen, and a 2010 decision) have somewhat narrowed the scope of this exception. They added a requirement that the unjust act must be "so grossly contrary to justice that it cannot be tolerated even considering the need for legal stability from res judicata" (著しく正義に反し、確定判決の既判力による法的安定の要請を考慮してもなお容認し得ないような特別の事情). ([Source 2])

- The 1998 case found that gross negligence in providing incorrect information (leading to defective service) did not meet this high bar for intentional harm. The 2010 case also denied a tort claim where a party allegedly obtained a judgment through false claims, emphasizing the high threshold.

- Despite this narrowing, some lower court cases have still found tortious acquisition of judgment, particularly where deceit was clear. ([Source 2])

- Academic Debate: ([Source 3])

- Traditional View (Negative/Retrial Primacy): Historically, the dominant view was that a final judgment, even if flawed, is binding unless overturned through a retrial. A separate tort claim contradicting it would generally be impermissible due to res judicata. Some within this view allowed for a tort claim only in exceptional cases where the prior judgment was "clearly contrary to justice."

- Affirmative View (Broader Allowance of Tort Claims): Criticizing the rigidity of the retrial system, this view argues for wider admissibility of tort claims, especially where procedural guarantees were lacking in the prior suit (which might even render the prior judgment void). Even this view often requires strict scrutiny akin to retrial grounds.

- Current Theories: Modern theories often focus on the justification for res judicata (procedural guarantee). If the prior proceeding lacked such guarantees for the wronged party, the res judicata might be weakened or inapplicable, allowing a tort claim. Others focus on balancing legal stability with substantive justice, permitting tort claims when the injustice of the prior judgment acquisition is severe.

- Application to the Facts of This Case: The Supreme Court found that D's conduct—settling the case and promising to withdraw it, then failing to do so and not informing D's own lawyer, leading P to reasonably believe the litigation was over and thus not participate—raised a strong suspicion of conduct "contrary to justice." P was effectively prevented from defending in the Prior Suit because of D's actions (or inactions) following the settlement. The Court emphasized that if P had known D would proceed, P would have appeared and raised the settlement as a defense.

This 1969 Supreme Court decision represents an important, albeit subsequently refined, avenue for seeking redress when a party has been harmed by a judgment obtained through serious misconduct by the opposing party. It balances the strong principle of res judicata with the imperative of preventing egregious abuses of the legal process, allowing a tort claim as an alternative or concurrent remedy to retrial in exceptional circumstances.