Too Late to Annul? Japan's Supreme Court on Bigamous Marriages Already Ended by Divorce

Date of Judgment: September 28, 1982

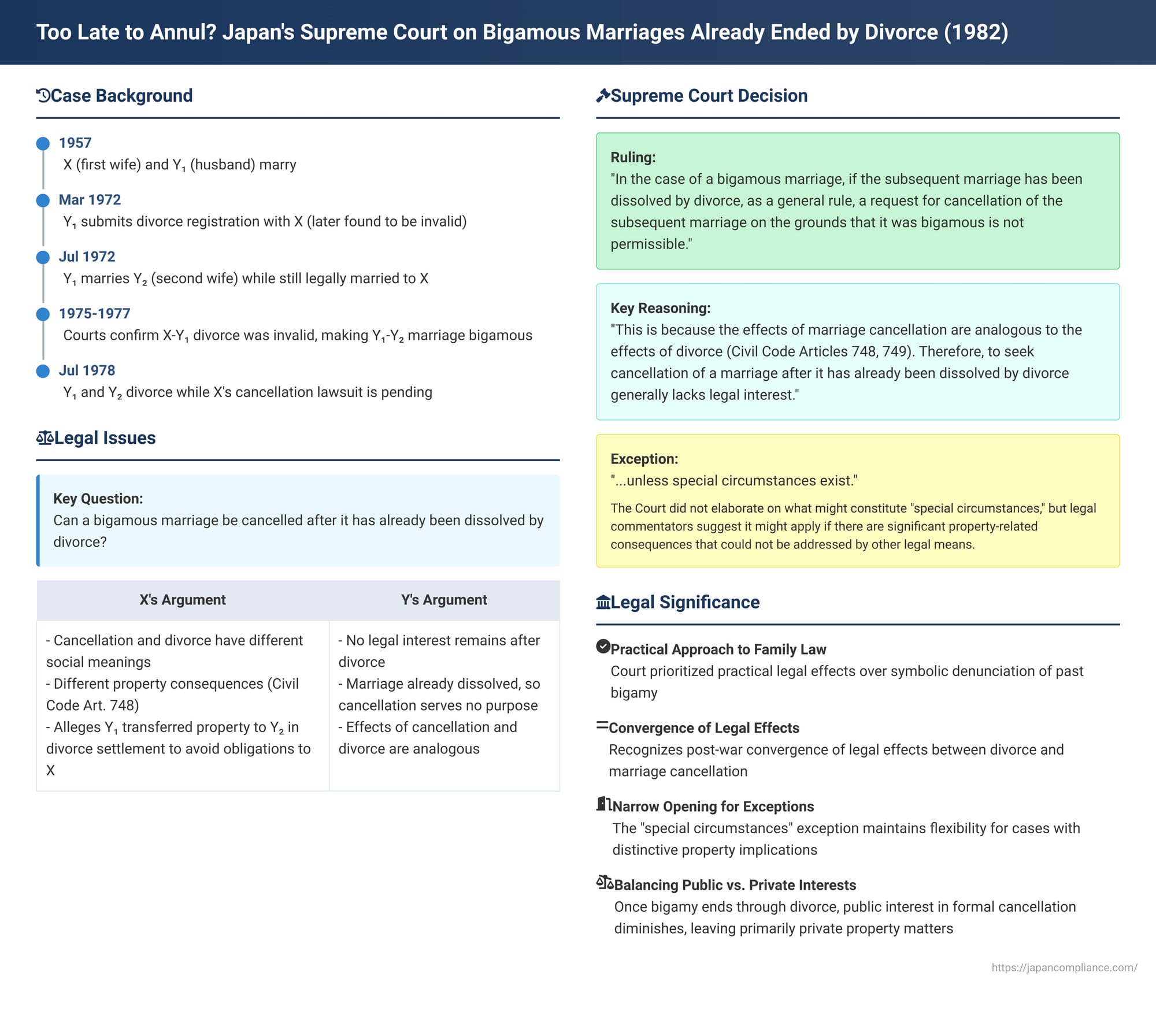

Bigamy—the act of entering into a marriage while already being legally married to another person—is prohibited under Japanese law (Civil Code Article 732). A subsequent marriage contracted in violation of this prohibition is not automatically void but is voidable, meaning it can be cancelled through legal action (Civil Code Article 744). But what happens if this bigamous second marriage is itself dissolved by a divorce before any legal action is taken to cancel it on the grounds of bigamy? Does the first, lawful spouse (or any other party entitled to seek cancellation) still possess a "legal interest" in having the now-defunct second marriage formally cancelled as bigamous? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this complex intersection of family law principles in a significant decision on September 28, 1982 (Showa 54 (O) No. 226).

The Tangled Web: A Prior Marriage, An Invalid Divorce, and a Bigamous Union

The case involved a complicated marital history. X (the first wife) and Y₁ (the husband) were married on June 3, 1957, and had two children. Years later, on March 21, 1972, Y₁ submitted a divorce registration, purportedly dissolving his marriage with X. Shortly thereafter, on July 22, 1972, Y₁ registered a marriage with Y₂ (the second wife), and they subsequently had a child.

However, the divorce between X and Y₁ was not straightforward. X initiated legal proceedings to have it declared invalid, alleging that Y₁ had deceived her into signing the divorce form and that, although she had later revoked her consent to the divorce before its submission, Y₁ had submitted the form anyway. X's claim was successful. On June 10, 1975, the Osaka District Court confirmed that the divorce between X and Y₁ was indeed invalid. This ruling was subsequently upheld by the Osaka High Court on January 28, 1977, and finally by the Supreme Court on September 26, 1977, making the invalidation of X and Y₁'s divorce definitive.

With her marriage to Y₁ legally re-established as continuously valid, X had her status as Y₁'s wife restored in the family register on October 15, 1977. Following this, X filed the lawsuit that led to the Supreme Court decision under discussion. She sought the cancellation of the marriage between Y₁ and Y₂ (the "subsequent marriage") on the grounds that it was bigamous, given that her own marriage to Y₁ was still legally in effect when Y₁ married Y₂.

The first instance court (Osaka District Court, July 18, 1978) sided with X, finding the marriage between Y₁ and Y₂ to be bigamous and ordering its cancellation. However, a pivotal event occurred while this cancellation case was pending appeal: on July 27, 1978, Y₁ and Y₂ registered a divorce by mutual agreement, also settling custody of their child.

The Lower Courts' Diverging Views on the Effect of the Divorce

This divorce between Y₁ and Y₂ dramatically changed the legal landscape for the appellate court (Osaka High Court, December 13, 1978) handling X's cancellation suit. The appellate court overturned the first instance judgment and dismissed X's action. Its reasoning was that, according to Article 748, paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, the effect of a marriage cancellation is prospective only (it does not retroactively invalidate the status aspects of the marriage from its inception). Therefore, since the subsequent marriage between Y₁ and Y₂ had already been dissolved by their divorce, there was no longer a remaining "legal interest" (hōritsu-jō no rieki) in pursuing its cancellation.

X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other points, that marriage cancellation and divorce have different social meanings and distinct effects on property relations, citing Civil Code Article 748, paragraphs 2 and 3 (which deal with unjust enrichment and damages upon marriage cancellation). She also alleged that the divorce between Y₁ and Y₂ was a sham intended to hide assets from her, with Y₁ having transferred property to Y₂ as part of their divorce settlement.

The Supreme Court's Decision: No Cancellation After Divorce, As a General Rule

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the appellate court's decision to dismiss her suit for cancellation.

The Core Principle:

The Court laid down a clear general rule: "In the case of a bigamous marriage, if the subsequent marriage has been dissolved by divorce, as a general rule, a request for cancellation of the subsequent marriage on the grounds that it was bigamous is not permissible, unless special circumstances exist."

Rationale: Similar Effects, Hence No Lingering Legal Interest:

The Supreme Court's reasoning was grounded in the similarity of legal effects between marriage cancellation and divorce: "This is because the effects of marriage cancellation are analogous to the effects of divorce (Civil Code Articles 748, 749). Therefore, to seek cancellation of a marriage after it has already been dissolved by divorce generally lacks legal interest, except in cases of special circumstances."

Since the primary outcome of a cancellation—the termination of the marital relationship—had already been achieved through the divorce of Y₁ and Y₂, the Court found that pursuing a cancellation generally served no further distinct legal purpose.

Application to the Specific Case:

The Court noted that X and Y₁'s prior marriage was confirmed as valid (due to their own divorce being invalidated), which consequently rendered the subsequent marriage between Y₁ and Y₂ bigamous at its inception. However, during the pendency of X's suit to cancel this bigamous subsequent marriage, Y₁ and Y₂ divorced. The Court concluded: "Therefore, in this case, where no assertion or proof of special circumstances has been made, it must be said that seeking cancellation of the subsequent marriage on the grounds of bigamy is no longer permissible." The appellate court's conclusion was thus deemed justifiable.

The "Special Circumstances" Exception: A Narrow Opening?

Crucially, the Supreme Court did not entirely close the door on post-divorce cancellations. It acknowledged an exception for "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō). While the judgment itself does not elaborate extensively on what these might entail, legal commentary on the case suggests that this exception would likely apply if there are clear and significant differences in property-related outcomes between a cancellation and a divorce that cannot be addressed by other means.

For instance, X had alleged that Y₁ made an excessive property division to Y₂ upon their divorce, possibly to shield assets from X (the first wife). Could this constitute a "special circumstance"? One academic view suggests that if such actions cause factual disadvantage to the first spouse, allowing cancellation might be considered. However, another view posits that even in such situations, the first spouse might have alternative legal remedies, such as a creditor's right to seek revocation of a fraudulent conveyance or an unfair property division, making the necessity of cancelling the (already dissolved) marriage debatable. The bar for establishing "special circumstances" appears to be high, reserved for situations where cancellation is the only viable path to address a distinct legal prejudice that divorce alone does not resolve.

Why Does the Law Distinguish Between "Cancellation" and "Divorce" in This Context?

Understanding the Supreme Court's reasoning requires appreciating the legal nuances and historical context surrounding marriage cancellation versus divorce in Japan.

- Historical Context and Property Rights: Before World War II, under the old Civil Code, marriage cancellation could have significantly different property consequences compared to divorce, particularly concerning the recovery of assets by an aggrieved party. Cancellation was a more potent tool for rectifying property imbalances arising from flawed marriages.

- Post-War Convergence of Effects: The post-war revision of the Civil Code brought the legal effects of marriage cancellation much closer to those of divorce. Many provisions applicable to divorce, such as those concerning property division (Civil Code Article 768), termination of affinity relationships (Article 728), and decisions regarding a child's surname and parental authority (Articles 790, 819), were made applicable by analogy to marriage cancellation (via Article 749). This convergence has progressively reduced the distinct legal advantages of pursuing cancellation once a divorce has already dissolved the marriage. Further revisions in 2003 explicitly incorporated more divorce-related articles into the scope of Article 749, reinforcing this trend.

- Social Meaning vs. Legal Effect: Some argue that cancellation serves to formally acknowledge and condemn the inherent legal flaw in a marriage's formation (such as bigamy), whereas a divorce dissolves a marriage that was presumptively validly formed. However, the Supreme Court in this case appeared to prioritize the practical legal effects and the existing status of the relationship (i.e., already dissolved) over a purely symbolic denouncement of its flawed origin.

Public Interest vs. Private Interests in Post-Divorce Cancellation

Once a bigamous subsequent marriage is dissolved by divorce, the actual state of bigamy ceases to exist. From a public interest perspective, the need to condemn the past bigamous union by formally cancelling it is significantly diminished. The primary objective of preventing ongoing bigamous relationships is achieved by the divorce.

The remaining issues are typically private matters, predominantly concerning the financial and property settlements between the parties to that now-dissolved subsequent marriage (Y₁ and Y₂). As a general principle, the first spouse (X) cannot directly intervene in the property settlement of her husband's separate, subsequent marriage, even if it was bigamous, once that marriage has ended. Her financial claims would primarily be against her own husband, Y₁.

Conclusion: Pragmatism Prevails in Addressing Dissolved Bigamous Unions

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1982 decision provides crucial clarification on a unique and complex area of family law. It establishes that, as a general rule, once a bigamous subsequent marriage has been terminated by divorce, the legal interest in seeking its cancellation on the grounds of bigamy is lost. This pragmatic approach is rooted in the understanding that the legal consequences of marriage cancellation and divorce have largely converged in modern Japanese law, rendering a post-divorce cancellation often redundant.

While an exception for "special circumstances" remains, suggesting a path for cancellation if significant and otherwise irremediable legal prejudice can be demonstrated (particularly concerning property rights), the ruling emphasizes finality once a marriage, even a flawed one, has been formally dissolved. It reflects a judicial focus on the practical outcomes and existing legal statuses of the parties rather than pursuing a formal denunciation of a union that no longer exists.