Too Connected to a Foreign Lawsuit? Japanese Supreme Court Declines Jurisdiction in International Defamation Case

Date of Judgment: March 10, 2016

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

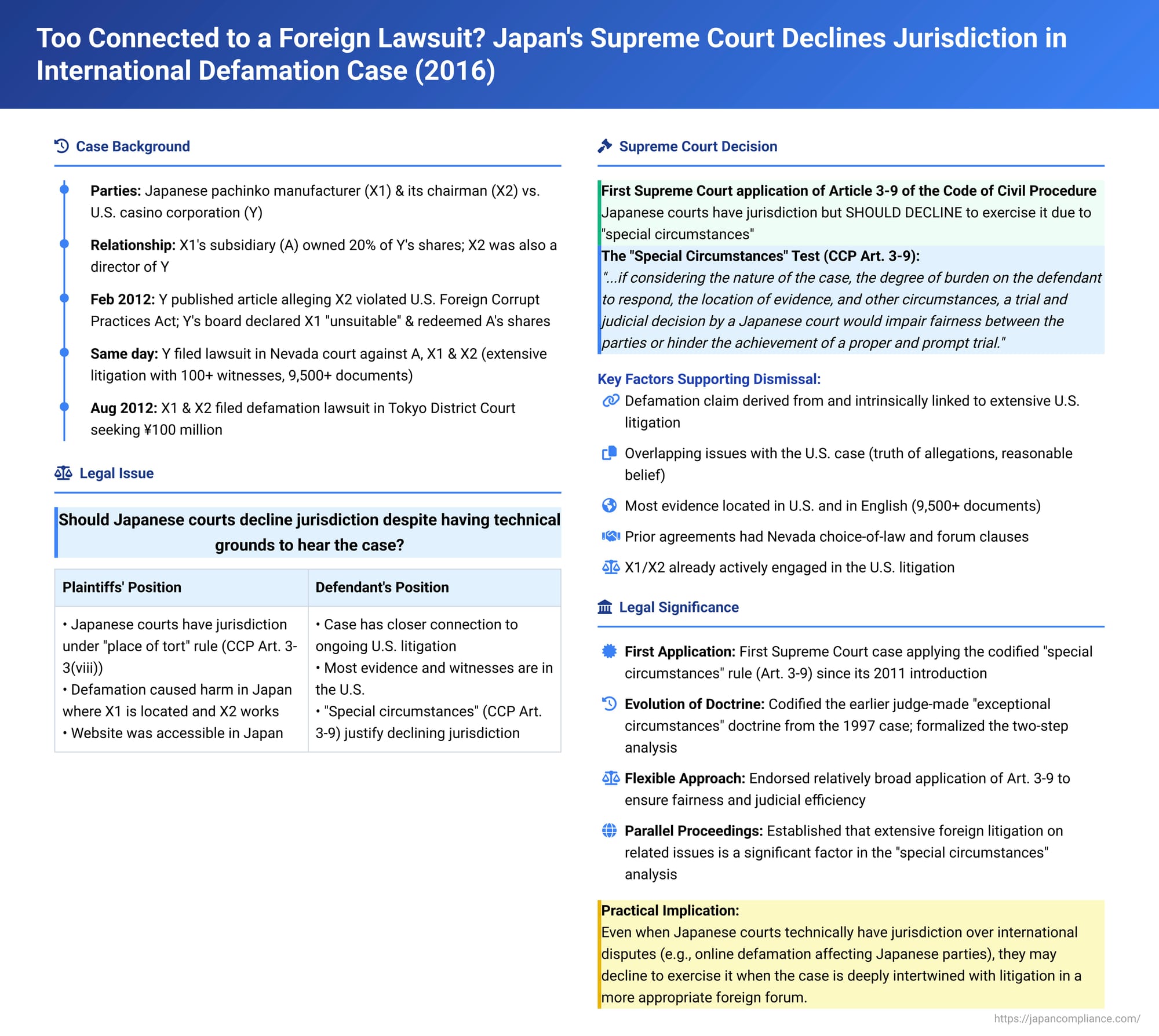

Even when Japanese courts technically have the authority to hear an international case, they possess a statutory power to decline jurisdiction if "special circumstances" suggest that proceeding would be unfair to the parties or hinder a proper and efficient trial. A Supreme Court decision on March 10, 2016, provided the first top-court application of this codified rule (Article 3-9 of the Code of Civil Procedure). The case involved a defamation claim brought in Japan by a Japanese corporation and its chairman against a U.S. corporation, where the allegedly defamatory statements were closely linked to extensive ongoing litigation in the United States.

The Factual Background: Defamation Allegations Amidst U.S. Corporate Battles

The dispute unfolded against a backdrop of complex corporate and legal maneuvering:

- X1 (Plaintiff): A Japanese corporation primarily involved in manufacturing and selling pachinko gaming machines.

- X2 (Plaintiff): The chairman of X1's board of directors.

- Y (Defendant): A U.S. corporation based in Nevada, principally engaged in casino operations. X2 also served as a director on Y's board.

- A (X1's U.S. Subsidiary): A Nevada corporation, subsidiary to X1, which held approximately 20% of Y's issued shares.

- The Disputed Article and Underlying Allegations: Y commissioned a U.S. law firm to investigate potential misconduct by X2. The law firm produced a report ("the Report") alleging that X2 and his associates appeared to have engaged in activities violating the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), such as bribing government officials in the Philippines and South Korea. Based on this Report, Y's board of directors determined that A and X1 were "unsuitable persons" under Y's articles of incorporation and resolved to forcibly redeem the shares in Y held by A. On February 19, 2012, Y published an article on its website ("the Article") outlining these allegations of FCPA violations by X2 and detailing the board's decision to redeem A's shares.

- Parallel U.S. Litigation: On the same day the Article was published, Y initiated a lawsuit against A, X1, and X2 in a Nevada state court. Y sought a declaration that its actions (including the share redemption) were lawful and damages from X2 for alleged breach of fiduciary duty. In response, A and X1 filed counterclaims in the Nevada litigation, challenging the validity of Y's board resolution and seeking an injunction and damages. This U.S. litigation involved extensive discovery, with around 100 witnesses and approximately 9,500 documents, the majority of which were in English, and most witnesses resided in the U.S. or other non-Japanese speaking locations.

- The Japanese Lawsuit: In August 2012, X1 and X2 filed the present lawsuit against Y in the Tokyo District Court. They claimed that Y's publication of the Article on its website constituted defamation and had damaged their reputation and credit, seeking 100 million yen in consolation money.

The Tokyo District Court found that because the alleged reputational harm occurred in Japan (where X1 is based and X2 is its chairman, and where the website was accessible), Japanese courts had jurisdiction under the "place of tort" rule (Article 3-3(viii) of the Code of Civil Procedure, CCP). However, it then dismissed the lawsuit, citing "special circumstances" under Article 3-9 of the CCP. The Tokyo High Court upheld this dismissal. X1 and X2 appealed to the Supreme Court.

Jurisdiction Established, But Should It Be Exercised? The "Special Circumstances" Test

The Supreme Court first affirmed that Japanese courts would generally have jurisdiction over the defamation claim. Since Y, a Nevada corporation, published the article online, and this allegedly caused harm to the reputation and credit of the Japanese corporation X1 and its chairman X2 in Japan, the case fell under CCP Article 3-3(viii) (jurisdiction where the tort was committed, which includes the place where the injurious result occurred).

The pivotal question, however, was whether this jurisdiction should be declined due to "special circumstances" (特別の事情 - tokubetsu no jijō) as stipulated in Article 3-9 of the CCP. This provision allows a court to dismiss a suit, in whole or in part, even if jurisdiction otherwise exists, if "considering the nature of the case, the degree of burden on the defendant to respond, the location of evidence, and other circumstances, a trial and judicial decision by a Japanese court would impair fairness between the parties or hinder the achievement of a proper and prompt trial."

The Supreme Court's Application of "Special Circumstances" (CCP Article 3-9)

The Supreme Court meticulously examined the factors and concluded that such "special circumstances" indeed existed, justifying the dismissal of the Japanese lawsuit:

- Derivative Nature of the Japanese Lawsuit: The defamation claim in Japan was intrinsically linked to and "derived from" the larger, pre-existing, and ongoing corporate dispute in the U.S. litigation. This U.S. litigation centered on Y's share redemption and the underlying allegations of FCPA violations by X2.

- Overlapping Issues and Predominant Location of Evidence: The primary issues in the Japanese defamation suit—namely, the truth of the facts asserted in Y's website Article and whether Y had reasonable grounds to believe them true—were largely common or closely related to the factual and legal issues being contested in the U.S. litigation. The vast majority of evidence pertinent to these core issues (numerous documents, testimony from around 100 witnesses) was located primarily in the United States and was mostly in English.

- Parties' Reasonable Expectations: The Court noted that previous agreements between X1/A and Y concerning investments and Y's management contained Nevada choice-of-law and choice-of-forum clauses. This suggested that both X1/X2 and Y had reasonably anticipated that disputes relating to Y's corporate governance and related matters would be negotiated or litigated in the United States.

- Plaintiffs' Active Engagement in U.S. Litigation: X1 and X2 were not merely passive defendants in the Nevada lawsuit; they had actively responded and filed substantial counterclaims. Therefore, requiring them to pursue their defamation claim within the U.S. legal system (potentially as part of or in conjunction with the existing U.S. litigation) would not impose an excessive new burden on them.

- Defendant's Burden of Litigating in Japan: Conversely, compelling Y to litigate these U.S.-centric factual issues, involving evidence predominantly located in the U.S. and in English, within a Japanese court would impose an excessive burden on Y.

Considering these cumulative factors, the Supreme Court concluded that "special circumstances" under CCP Article 3-9 were present, as hearing the case in Japan would impair fairness between the parties and hinder the realization of a proper and prompt trial. The dismissal of the suit by the lower courts was therefore affirmed.

Significance: The First Supreme Court Application of CCP Article 3-9

This decision is highly significant as it was the first time the Supreme Court applied the codified Article 3-9 of the Code of Civil Procedure to dismiss a lawsuit based on "special circumstances."

- Continuity and Evolution of the Doctrine: Article 3-9 was introduced in the 2011 amendments to the CCP, effectively codifying a principle that had been developing in Japanese case law. The 1997 Supreme Court "deposit return" case (see case 83 in this series) had earlier established the doctrine of "exceptional circumstances" (tokudan no jijō) allowing courts to decline jurisdiction based on jōri (reason/natural justice) if exercising it would be unfair or improper. The codified Article 3-9 provides a more structured, albeit still discretionary, framework. The Supreme Court in the present case followed the now-preferred two-step analysis: first, determining if a basis for jurisdiction exists under CCP Articles 3-2 to 3-8, and then, if jurisdiction is affirmed, considering whether "special circumstances" under Article 3-9 warrant a dismissal.

- Scope of "Special Circumstances": This ruling demonstrates the Supreme Court's willingness to endorse a relatively broad application of Article 3-9, permitting dismissal even when a prima facie jurisdictional ground (like the place of tort resulting in injury in Japan) is clearly met. Academic commentary notes that there's an ongoing discussion regarding how restrictively or expansively Article 3-9 should be applied. Some argue for cautious use to protect plaintiffs' access to courts, while others (including those involved in drafting the legislation) see it as a vital tool for judicial discretion to ensure fairness and manage dockets, akin to domestic rules on discretionary transfer of venue. This decision appears to align with the latter, more flexible view.

- Impact of Parallel Foreign Litigation: A key factor in this case was the extensive, pre-existing, and closely related litigation in the United States. The Supreme Court's heavy emphasis on the connection to this foreign lawsuit, the location of evidence there, and the parties' existing engagement in that forum signals that the existence of substantial parallel foreign proceedings can weigh heavily in the "special circumstances" analysis. Subsequent lower court decisions have also considered ongoing or concluded foreign litigation as a significant factor under Article 3-9.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 10, 2016, decision in this international defamation case provides important guidance on the application of Article 3-9 of the Japanese Code of Civil Procedure. It confirms that Japanese courts, while acknowledging jurisdiction for torts causing harm within Japan (such as online defamation), will carefully scrutinize the broader context of a dispute. Where a lawsuit in Japan is deeply intertwined with complex, ongoing litigation in a more appropriate foreign forum, and where the bulk of the evidence and the parties' expectations point abroad, Japanese courts may exercise their discretion to decline jurisdiction under the "special circumstances" provision to ensure fairness and the efficient administration of justice. This ruling underscores the courts' role in managing international jurisdiction thoughtfully in an increasingly interconnected world.