"To Contribute to the Public": Supreme Court Upholds Will Entrusting Devisee Selection to Executor

Date of Judgment: January 19, 1993 (Heisei 5)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 63 (o) No. 192 (Claim for Cancellation of Land and Building Ownership Transfer Registration, Claim for Confirmation of Non-Existence of Will Executor's Status)

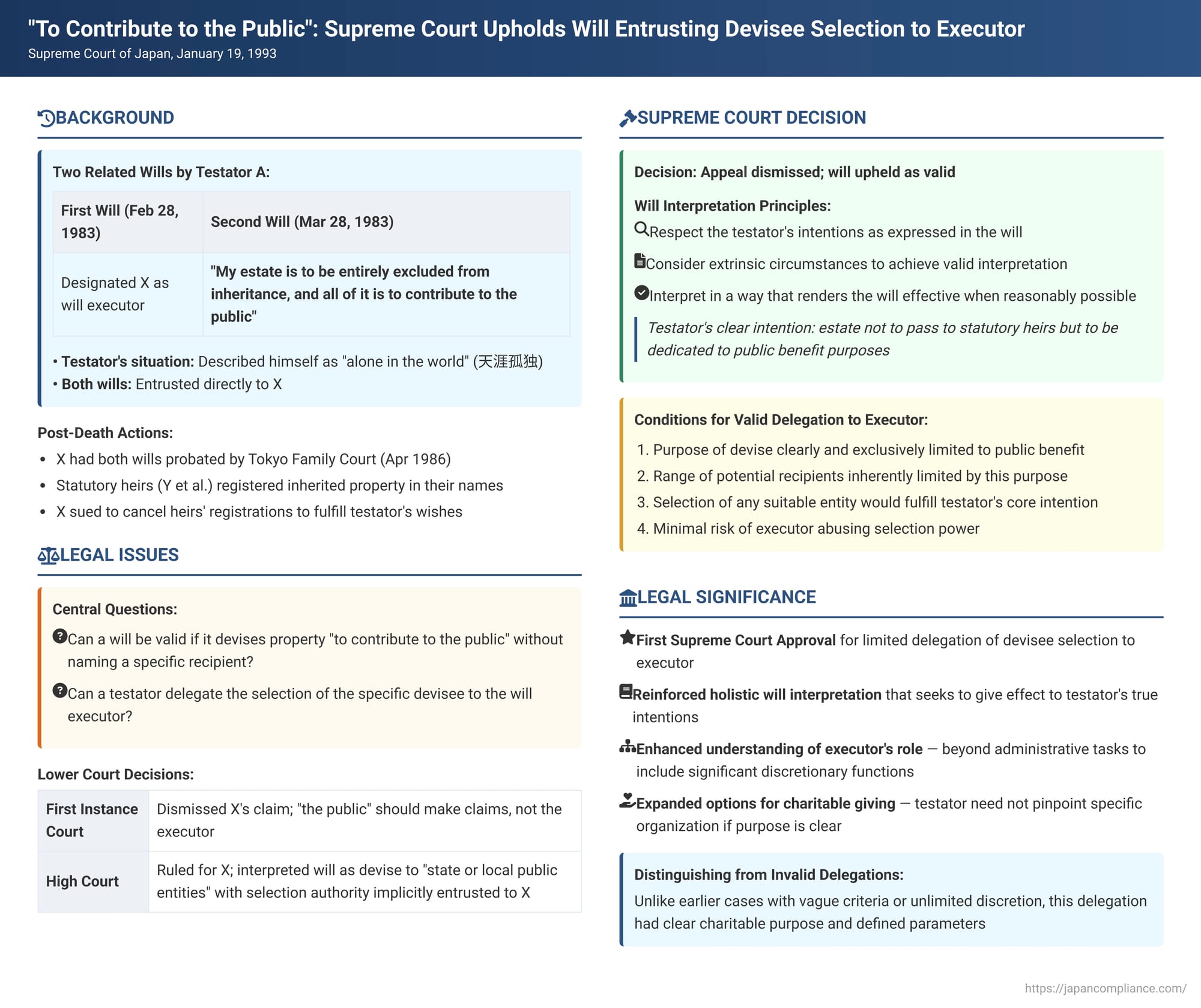

A fundamental principle of will-making is that the testator's intentions should be clearly expressed, particularly regarding who will benefit from their estate. However, what happens when a testator expresses a general charitable or public-benefit intent, such as devising their estate "to contribute to the public," without naming a specific recipient organization, but instead entrusts the selection of such an entity to their appointed will executor? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed the validity of such a testamentary disposition in a significant decision on January 19, 1993.

Facts of the Case: A Will for Public Good and an Executor's Role

The case involved the estate of A, who passed away on October 17, 1985.

- The Testator and His Circumstances: A had described himself as being "alone in the world" (天涯孤独 - tengai kodoku), indicating a sense of estrangement from his statutory heirs and a desire for his estate to serve a broader purpose.

- The Two Wills: A had created two separate holographic (handwritten) wills:

- Executor Designation Will (February 28, 1983): In this first will, A designated X (Kamejiro K. in the judgment), a relative of A's deceased wife, as his will executor. A entrusted this document directly to X.

- Main Devise Will (March 28, 1983): About a month later, after specifically requesting X to visit him again, A created a second holographic will in X's presence. This will contained the crucial clause: "My estate is to be entirely excluded from inheritance [by statutory heirs], and all of it is to contribute to the public" (遺産は一切の相続を排除し、全部を公共に寄与する - isan wa issai no sōzoku o haijo shi, zenbu o kōkyō ni kiyo suru). A also reiterated his solitary status to X at this time and entrusted this will to X as well.

- Post-Death Actions and Dispute: After A's death, X, acting as the designated will executor, had both wills formally probated by the Tokyo Family Court (in April 1986). X then notified A's legal heirs (his sisters, Y et al., who were the defendants/appellants) that he was assuming his duties as executor to carry out the terms of A's will.

However, Y et al. proceeded to register A's inherited real estate in their own names, based on their rights as statutory heirs, effectively ignoring the will. - Lawsuit by the Will Executor: X filed a lawsuit against Y et al., seeking the cancellation of their inheritance-based property registrations so that A's testamentary wish to contribute his estate to the public could be fulfilled. (Y et al. had also initiated a separate action, which was dismissed at the first instance, challenging X's legal status as will executor).

- Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance Court: This court dismissed X's claim. It did not directly rule on the validity of A's main devise will but took the view that if the estate was intended for "the public," then "the public" (or some representative entity thereof) should be the party to make a claim for the property, not X merely seeking cancellation of the heirs' registration.

- High Court (Original Appeal): The High Court reversed the first instance decision and ruled in favor of X. The High Court interpreted A's will—devising the estate "to contribute to the public"—as expressing a clear intention to make a comprehensive (or universal) devise to "the state or local public entities." Furthermore, it considered the earlier will designating X as executor in conjunction with the main devise will. It concluded that these two documents, read together, implicitly entrusted X with the authority to select a specific public entity from this category (state or local public bodies) to be the actual recipient of the devise. On this basis, the High Court found A's testamentary plan to be valid and held that X, as the duly appointed will executor, possessed the legal authority under the Civil Code (specifically Articles 1012 and 1013, concerning the rights and duties of will executors) to demand the cancellation of Y et al.'s improper inheritance registrations.

- Appeal by Heirs (Y et al.) to the Supreme Court: Y et al. appealed the High Court's decision, challenging the validity of the will and X's authority.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Will and the Executor's Role

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y et al., thereby affirming the High Court's decision that the will was valid and that X had the authority to act as executor.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was articulated in two main parts:

I. Principles of Will Interpretation and Application to A's Will:

- Fundamental Goal of Interpretation: The Court began by stating the general principles of will interpretation: the court must respect the testator's intentions as expressed in the will and interpret its meaning reasonably. Crucially, the interpretation should, as far as possible, lead to the will being considered valid and effective, as this approach best aligns with giving effect to the testator's wishes.

- Permissible Use of Extrinsic Evidence: To achieve a valid and effective interpretation, while the starting point must be the literal wording of the will, courts are permitted to consider extrinsic circumstances. This includes the background and events leading up to the will's creation and the testator's personal situation and environment at that time.

- Ascertaining A's True Intent: Applying these principles, the Supreme Court looked at the overall language of A's will documents and his situation at the time of their creation (his estrangement from his statutory heirs and his statement about being "alone in the world"). From this, the Court found it clear that A's true intention was for his estate not to pass to his statutory heirs (Y et al.) but rather for it to be entirely dedicated to public benefit purposes.

- Interpreting "To Contribute to the Public": The specific phrasing used by A—"to contribute to the public"—without explicitly naming a recipient entity, was interpreted by the Court as an intention to make a comprehensive devise of his entire estate to an organization or entity capable of achieving this broad public benefit purpose. The Supreme Court noted that this could include the state or local public entities (as the High Court had suggested as typical examples) but also extended to public interest corporations (under the then-Article 34 of the Civil Code, pre-dating the 2006 reforms), school corporations, social welfare corporations, and similar bodies.

- Entrusting Selection to the Will Executor: The Court then considered the sequence of events: A first made a will specifically designating X as his executor and entrusted it to X. He then specifically requested X to visit him again for the purpose of creating the main devise will, which he also made in X's presence and entrusted to X. Taking this entire context into account, the Supreme Court concluded that A's testamentary plan—as expressed through both will documents—included the intention to entrust X, in his capacity as the designated will executor, with the specific task of selecting an appropriate entity from among such public-benefit organizations to be the ultimate devisee of the estate.

The Court found that this interpretation both fulfilled A's overarching charitable intent and resolved any potential issue of the devisee lacking specific identification in the will itself, because the power to specify was validly delegated.

II. Validity of a Will Entrusting Devisee Selection to a Will Executor:

- Legitimate Need for Such Wills: The Supreme Court acknowledged that testators may have legitimate reasons and a genuine need to create wills that do not name a specific devisee directly but instead delegate the selection to a trusted will executor.

- Conditions for Upholding Such Delegation in This Case: The Court found that A's will, which included such a delegation, could be upheld as valid in this particular instance due to several key safeguards and circumstances:

- The purpose of the devise was clearly and exclusively limited to public benefit. This provided a guiding principle for the executor's selection.

- The range of potential recipients (devisees) was also inherently limited by this public benefit purpose – i.e., to organizations or entities capable of fulfilling such a purpose.

- Given this specific public benefit purpose, the selection of any suitable entity from within this defined range would not fundamentally deviate from the testator's core intention. The testator was primarily concerned with the purpose, not necessarily with one specific organization over another, as long as the purpose was served.

- Consequently, the risk of the selector (will executor X) abusing their power of selection or acting contrary to the testator's wishes was deemed minimal.

- Conclusion on Validity: Given these limiting factors and safeguards, the Supreme Court concluded that there was no reason to invalidate A's will.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1993 Supreme Court decision is highly significant for its approach to will interpretation and its groundbreaking stance on the validity of entrusting the selection of a devisee to a will executor under certain conditions.

- Reinforcement of Holistic and Purposive Will Interpretation: The case strongly reaffirms the principle that Japanese courts will strive to understand and give effect to a testator's true intentions by looking at the will document as a whole, considering the testator's personal circumstances, and interpreting the will in a way that renders it effective if reasonably possible (a concept often referred to as "effective interpretation" or 有効解釈 - yūkō kaishaku). This approach was previously indicated in cases like the Supreme Court decision of Showa 58.3.18 (March 18, 1983).

- First Supreme Court Approval for Limited Delegation of Devisee Selection: This was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly validated a will that delegates the choice of the ultimate devisee to a will executor. This was a departure from more traditional views which often held that the testator must personally and unequivocally identify the recipient in the will itself.

- Key Conditions for Valid Delegation of Devisee Selection: The PDF commentary accompanying this case suggests that the ruling implies several important conditions for such a delegation to be considered valid:

- There must be a clearly defined and overriding purpose for the devise (in this case, "to contribute to the public").

- The range of potential recipients must be sufficiently limited and identifiable by that purpose, ensuring that the executor's choice remains within the testator's intended ambit.

- The circumstances should indicate that the testator's primary concern was the fulfillment of this purpose, rather than benefiting a specific, pre-determined individual or entity (i.e., the testator is essentially indifferent as to which qualifying entity receives the devise, as long as the overarching charitable or public aim is met).

- There must be a low risk of the person entrusted with selection (the will executor) abusing their discretion or acting contrary to the testator's underlying wishes.

- Distinction from Vague or Unfettered Delegations: The PDF commentary contrasts this decision with an older Daishin'in (Great Court of Cassation) case from Showa 14 (1939). In that earlier case, a will granting very broad and ill-defined discretion to a third party to "dispose of [a part of the estate] by devise, distribution, or other acts of donation by such methods as they deem appropriate" was held invalid. The reason was that the lack of clear criteria for either the selection of beneficiaries or the purpose of the disposition made it impossible to ascertain the testator's true intent, leading to a high risk of the entrusted party's actions diverging from what the testator might have wished. The 1993 Supreme Court case is distinguishable because of the clear "public benefit" purpose and the implied (and judicially recognized) range of suitable entities capable of fulfilling that purpose.

- The Will Executor's Enhanced Role: This decision supports a somewhat broader understanding of the will executor's role. Beyond purely administrative tasks, an executor can be entrusted with significant discretionary functions, such as selecting a devisee, provided this is clearly intended by the testator and the delegation is framed within ascertainable limits and purposes. The PDF commentary notes that the 2018 amendments to the Civil Code (effective 2019) now explicitly state in Article 1012, Paragraph 1, that a will executor has the right and duty to perform "all acts necessary for the management of inherited property and any other acts necessary for the execution of the will." The powers recognized in this 1993 judgment can be seen as an example of such necessary acts to realize the testator's specific testamentary plan.

- The Significance of "Public Benefit" as a Guiding Purpose: The fact that A's devise was for "public benefit" was a critical element in the Court's reasoning. This provided an objective and socially recognized standard to guide the executor's discretion and to ensure that the selection would align with A's broad charitable intent. Whether a similar delegation of devisee selection would be upheld for purely private beneficiaries without such a clear, limiting, and altruistic guiding purpose remains a more open question.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1993 decision is a landmark ruling that demonstrates a flexible and purposive approach to will interpretation, particularly in cases involving charitable or public-benefit devises. By upholding a will that allowed the executor to select a specific public-benefit entity as the devisee, the Court recognized that testators may have legitimate needs for such arrangements and that their intentions can be given effect if there are sufficient safeguards—such as a clearly defined purpose and a limited range of potential recipients—to ensure the executor's choice aligns with the testator's overarching wishes and minimizes the risk of abuse. This judgment empowers testators to make broader charitable bequests even without pinpointing a specific organization at the time of will-making, provided they entrust this final selection to a reliable executor within a clearly defined framework of intent.