Timing Your Challenge: Navigating Lawsuit Deadlines for Land Expropriation Cases in Japan

Judgment Date: November 20, 2012

Case Number: Heisei 24 (Gyo-Hi) No. 20 – Claim for Revocation of Administrative Review Decision and Original Disposition

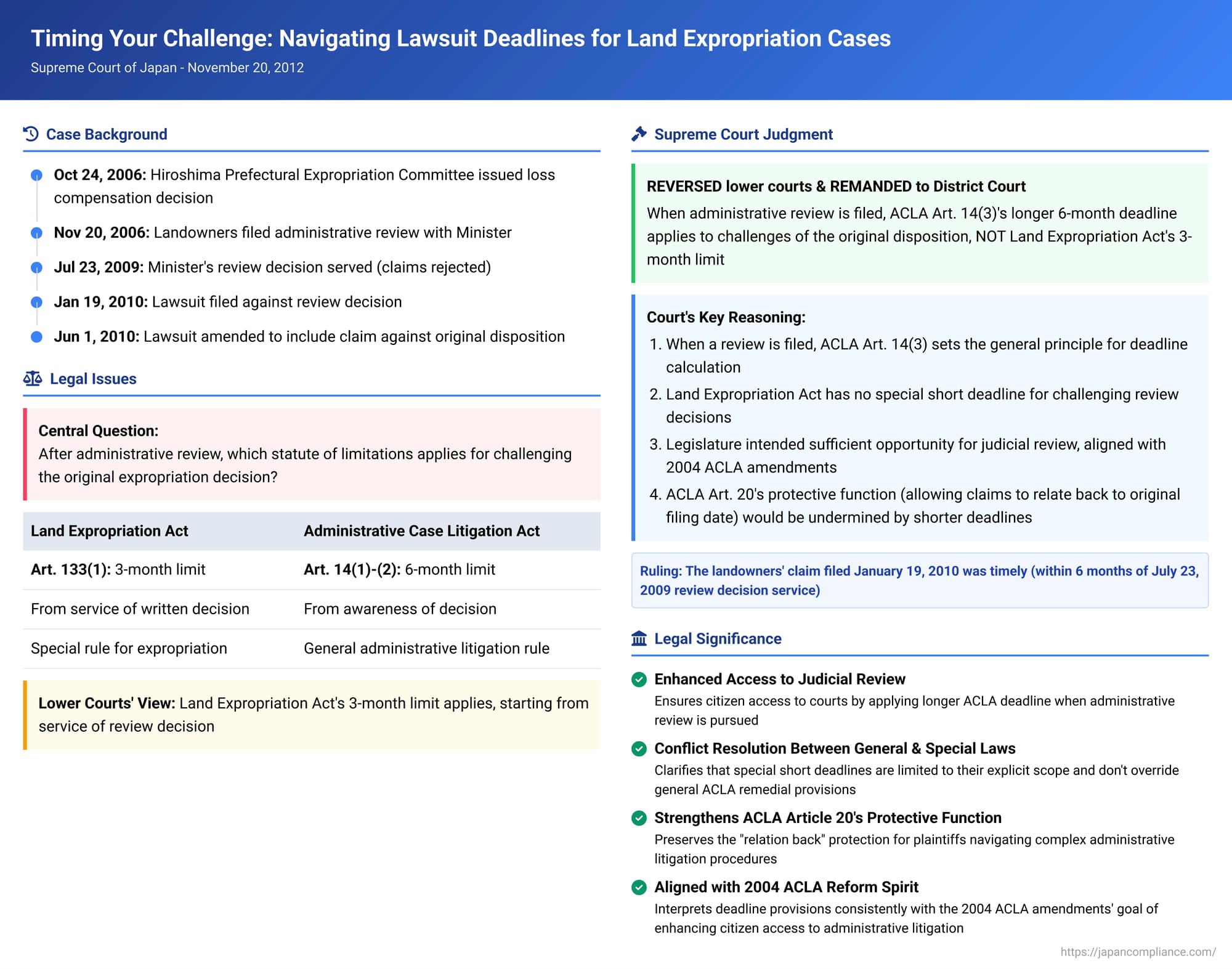

Navigating the statutes of limitations in administrative law can be complex, especially when specific laws with unique deadlines interact with general procedural rules, and when an administrative review process precedes a court challenge. A 2012 Japanese Supreme Court decision provided crucial clarity on the time limits for filing a lawsuit to revoke an Expropriation Committee's decision on land compensation, particularly after an administrative review has been sought against that decision. This case highlights the judiciary's efforts to balance the need for legal stability with ensuring citizens have an adequate opportunity for judicial redress.

The Case at Hand: A Land Compensation Dispute

The dispute involved landowners (X and others, including an appointed party A) affected by a land readjustment project undertaken by Higashi-Hiroshima City. The Hiroshima Prefectural Expropriation Committee issued a decision on October 24, 2006, concerning loss compensation and its timing (referred to as the "original disposition" or "this loss compensation decision").

Dissatisfied with this original disposition, X and others filed an administrative review (審査請求 - shinsa seikyū) with the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism on November 20, 2006. On July 22, 2009, the Minister issued a review decision (裁決 - saiketsu), rejecting their claims. An authenticated copy of this review decision was served on X and others on July 23, 2009.

Subsequently, on January 19, 2010, X and others filed a lawsuit seeking to revoke the Minister's review decision. Later, on June 1, 2010, they amended their lawsuit to add a claim seeking the revocation of the Expropriation Committee's original disposition, arguing it was illegal because the Committee had not dismissed an allegedly improper application from the city. The claim against the Minister's review decision was eventually dismissed on its merits and became final. The procedural issue before the Supreme Court concerned the timeliness of the added claim against the original Expropriation Committee decision.

The Legal Maze: General Rules vs. Special Provisions for Lawsuit Deadlines

The core of the dispute lay in interpreting the applicable statute of limitations:

- Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA) General Rules (Art. 14):

- Generally, a lawsuit to revoke an administrative disposition must be filed within 6 months from the day the person became aware of the disposition (Art. 14(1)) and, in any event, no later than 1 year from the date of the disposition (Art. 14(2)).

- Crucially, if an administrative review can be (and is) filed against a disposition, ACLA Art. 14(3) provides a special calculation for the person who filed the review: the 6-month and 1-year periods for challenging the original disposition begin to run from the day they became aware of the review decision or the date of the review decision, respectively. This ensures that pursuing an administrative review does not disadvantage the plaintiff by eating into their time to sue regarding the original disposition.

- Land Expropriation Act Special Rule (Art. 133(1)):

- The Land Expropriation Act contains a special, shorter statute of limitations. Article 133(1), introduced via amendments accompanying the 2004 ACLA revision, states that lawsuits concerning an Expropriation Committee's decision (excluding those about the amount of compensation) must be filed within an unextendable period of 3 months from the day the authenticated copy of the written decision was served. This provision aims to ensure the rapid stabilization of legal relations in land expropriation matters.

The lower courts (Hiroshima District Court and Hiroshima High Court) had ruled that the Land Expropriation Act's stricter 3-month limit applied even when an administrative review had been filed. They calculated this 3-month period from the date of service of the review decision. Since the claim against the original disposition was deemed filed on January 19, 2010 (due to ACLA Art. 20, which treats a later-added claim against an original disposition as filed when the initial suit against the review decision was filed ), and this was more than 3 months after July 23, 2009 (service of the review decision), the lower courts found the claim to be time-barred.

The Supreme Court's Clarification (November 20, 2012)

The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts' decisions regarding the timeliness of the claim against the original disposition and remanded the case to the District Court for a hearing on the merits.

Unpacking the Supreme Court's Reasoning

The Court meticulously analyzed the interplay between the general ACLA provisions and the special Land Expropriation Act rule:

- Legislative Intent of the 2004 ACLA Amendments: The 2004 revisions to the ACLA, which extended the general lawsuit period in Art. 14(1) from 3 to 6 months, were aimed at enhancing more effective relief for citizens' rights and interests, while still considering the need for legal stability.

- Purpose of Land Expropriation Act Art. 133(1): This special 3-month rule was introduced concurrently to ensure rapid finality for Expropriation Committee decisions, reflecting the public importance of land expropriation projects. However, this provision directly addresses challenges to the Committee's decision.

- Absence of a Special Short Period for Review Decisions in Expropriation Law: The Supreme Court highlighted that while the Land Expropriation Act created a special short deadline for challenging the Expropriation Committee's original decisions, it did not establish a similar special short deadline for lawsuits challenging the Minister's review decision (i.e., a decision on an administrative review against an Expropriation Committee's ruling). Therefore, lawsuits to revoke such review decisions fall under the ACLA's general time limits (6 months from awareness/1 year from decision date, per ACLA Art. 14(1) & 14(2)). The Court interpreted this legislative choice as intending to provide ample opportunity for parties to consider whether to challenge such review decisions.

- ACLA Art. 14(3) as the Guiding Principle When Review is Filed: The Court emphasized that ACLA Art. 14(3) sets the general principle for the statute of limitations for lawsuits against an original disposition when an administrative review has been filed. This provision aligns the period and its starting point (triggering from the review decision) with that for lawsuits against the review decision itself. The Supreme Court stated that any interpretation leading to a shortening of this period for the original disposition, based on a special law, requires careful and cautious consideration, especially in light of the ACLA's overarching goal of ensuring adequate opportunities for citizens to seek judicial relief.

- Consistency and Plaintiff Protection (ACLA Art. 20): The Court pointed to ACLA Art. 20, which allows a claim against an original disposition to be deemed filed at the time an initial claim against the review decision was filed, if the two are joined. This provision is designed to protect plaintiffs who might mistakenly file suit only against the review decision (perhaps overlooking the principle of original disposition primacy, where grounds for challenging the original disposition cannot typically be used to attack the review decision unless the review decision has its own flaws ). If the time limit for the original disposition suit were shorter than that for the review decision suit (in cases where a review has been filed), Art. 20's protective function could be partially nullified. By interpreting ACLA Art. 14(3) as applying the same (longer) deadline to both types of challenges when a review has been pursued, the utility of Art. 20 is consistently maintained.

The Outcome: ACLA's General Rule Prevails in This Specific Scenario

The Supreme Court concluded that when an administrative review is filed against an Expropriation Committee's decision:

- The statute of limitations for a lawsuit to revoke that original decision (the Committee's decision) is governed by ACLA Art. 14(3). This means the lawsuit must be filed within 6 months from the day the plaintiff became aware of the review decision, or within 1 year from the date of the review decision.

- The special 3-month limitation period in Land Expropriation Act Art. 133(1) does not apply in this scenario (i.e., when an administrative review has been filed against the Committee's decision and one is now challenging the Committee's original decision after the review decision). That shorter period is for cases where a party directly challenges the Committee's decision without first seeking administrative review.

Applying this to the case, since X and others' claim to revoke the original loss compensation decision was (through the effect of ACLA Art. 20) deemed filed on January 19, 2010—which was within 6 months of July 23, 2009 (when they were served with and became aware of the Minister's review decision)—it was timely.

Significance of the Ruling

This Supreme Court decision is significant for several reasons:

- It provides essential clarity on the complex interaction between general ACLA statute of limitations provisions and special provisions in individual administrative laws like the Land Expropriation Act, particularly when an administrative review step is involved.

- The ruling prioritizes ensuring an adequate opportunity for judicial review, consistent with the remedial aims of the 2004 ACLA amendments.

- It underscores that exceptions to general procedural rules, especially those that might curtail a citizen's right to access the courts, must be clearly and explicitly stated by the legislature for each specific scenario. Courts will be cautious about implying such restrictions broadly.

- The judgment offers valuable interpretation of ACLA Art. 20, reinforcing its role in protecting plaintiffs who navigate the procedural distinction between challenging an original disposition and a subsequent review decision.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2012 decision offers practical guidance for citizens and legal practitioners facing intricate procedural deadlines in administrative litigation. By holding that the general ACLA time limits apply to challenges of an original expropriation decision when an administrative review has first been pursued, the Court affirmed a more accessible path to judicial review. This judgment emphasizes a careful reading of legislative intent, ensuring that special, shorter deadlines are confined to their intended scope and do not inadvertently create procedural traps that could prematurely bar meritorious claims.