Timing is Everything: The Earth Belt Case and Proving 'Well-Known' Status in Japanese Unfair Competition Law

Judgment Date: July 19, 1988

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Numbers: Showa 61 (O) No. 30 & No. 31 (Claim for Injunction Against Manufacturing of Imitation Goods, etc.)

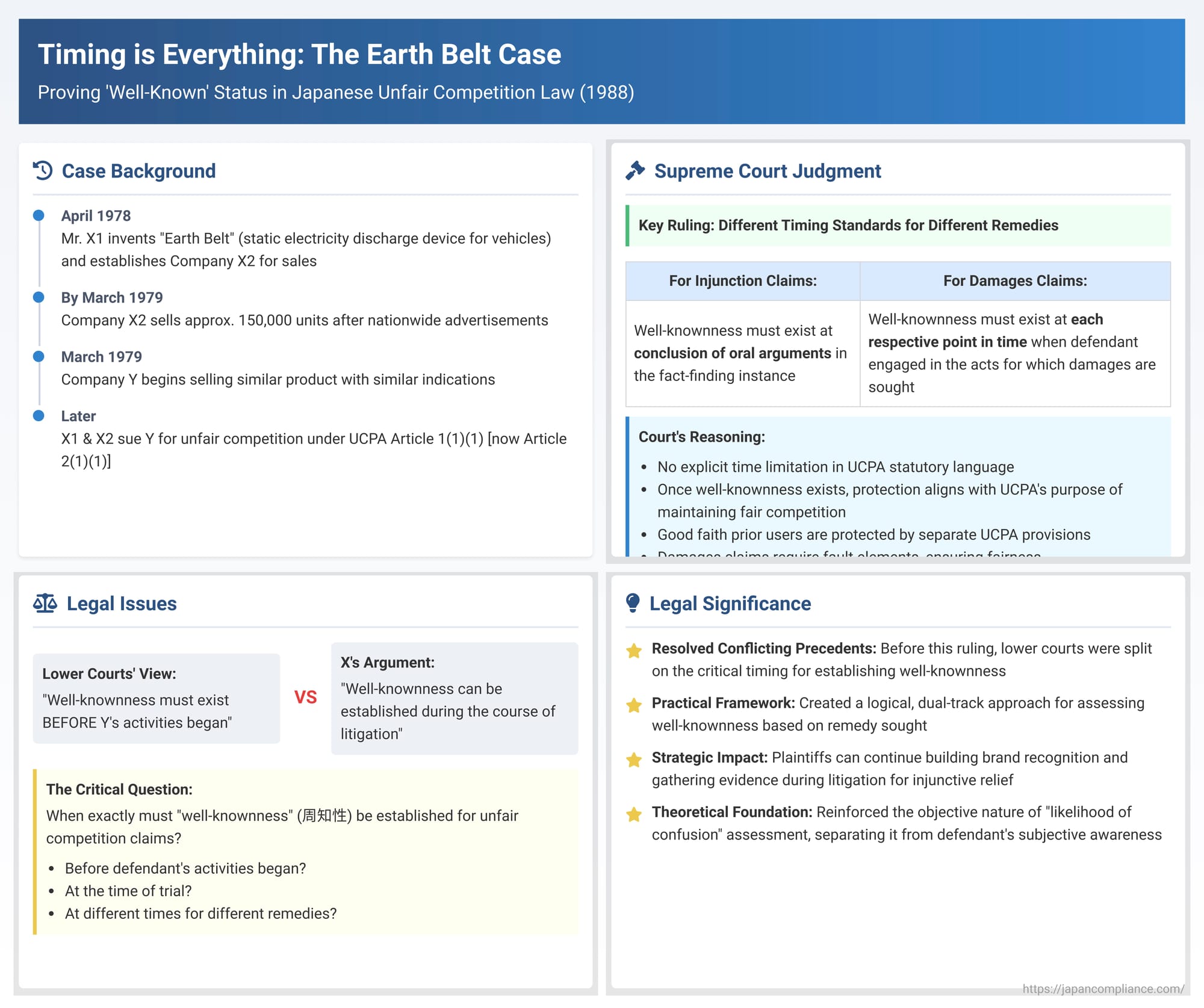

The "Earth Belt" (アースベルト - Āsu Beruto) case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1988, is a seminal judgment that provided crucial clarity on the timing for assessing whether a product indication has achieved "well-knownness" (周知性 - shūchisei) under Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA). This is a critical factor in determining whether a party can prevent others from using similar indications that cause confusion as to the source of goods or business. The Court distinguished the relevant assessment period for seeking an injunction from that applicable to claiming damages, establishing a framework that continues to influence unfair competition litigation in Japan.

The "Earth Belt" Dispute: A Spark of Competition

The case involved Mr. X1, who invented a vehicle static electricity discharge belt, which he named "Earth Belt." He commercialized this product in April 1978 and established Company X2 to handle its sales. The "X products" (Company X2's Earth Belts) were promoted through advertisements in magazines, newspapers, and on the radio, and were distributed and sold in major cities across Japan. By March 1979, approximately 150,000 units of the X products had been sold.

In March 1979, Company Y began selling its own version of an automotive static discharge belt ("Y products"). Mr. X1 and Company X2 (collectively "X") sued Company Y, alleging that the configuration of Y's products and the trademark Y used were confusingly similar to those of X's products and X's "Earth Belt" indication. X's claim was based on Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the old Unfair Competition Prevention Act (which corresponds to Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the current UCPA). This provision prohibits acts of unfair competition involving the use of another's well-known product or business indication in a manner that creates a likelihood of confusion. X sought an injunction to stop Company Y's manufacturing and sales activities, as well as monetary damages.

Lower Court Rulings Focused on Pre-Defendant Activity:

The Sendai District Court, and subsequently the Sendai High Court on appeal, dismissed X's claims. A key aspect of their reasoning was the timing for establishing well-knownness. The District Court explicitly stated that for X's claims to succeed, "the period during which well-knownness is possessed must be, at the latest, before Y's products were launched." Both lower courts found that X's "Earth Belt" product indication had not achieved the requisite level of well-knownness by the time Company Y commenced its sales in March 1979. Based on this finding, X's claims were rejected.

Mr. X1 and Company X2 appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Clarification on the Timing of Well-Knownness

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's decision (specifically, the part concerning Company X2's claims) and remanded that portion of the case for further proceedings. However, it dismissed Mr. X1's individual appeal. The core of the judgment was its definitive pronouncement on the critical date for assessing well-knownness under the UCPA:

The Court held: "When party A, asserting that its product indication is a well-known product indication under Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act, seeks an injunction or other remedies against party B, who is using a similar product indication, A's product indication must possess well-knownness at the point in time when B's actions, considered as acts of unfair competition, become problematic in relation to A's claim. Specifically:

- For an injunction claim (差止請求 - sashitome seikyū): A's product indication must be well-known as of the present time (which means the conclusion of oral arguments in the fact-finding instance of the trial, i.e., the district court or the high court if it re-examines facts).

- For a damages claim (損害賠償請求 - songai baishō seikyū): A's product indication must have possessed well-knownness at each respective point in time when B engaged in the acts of using the similar product indication for which damages are being sought."

The Supreme Court clarified that it is sufficient for the plaintiff (A) to establish well-knownness as of these respective critical dates. It is not a requirement that the plaintiff's indication must have been well-known before the defendant (B) commenced their activities using the similar indication.

Rationale Underpinning the Supreme Court's Stance:

The Court provided several reasons for this interpretation:

- Statutory Language: The text of UCPA Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 1 itself does not explicitly limit or specify the timing by which well-knownness must have been achieved.

- Purpose of the UCPA: The Court reasoned that once a factual state of well-knownness sufficient to warrant protection has been formed for a product indication, preventing acts that cause source confusion from that point forward aligns with the UCPA's fundamental objective of maintaining a fair competitive order.

- Protection of Good Faith Prior Users: This interpretation does not unduly prejudice parties who may have been using a similar indication in good faith before the plaintiff's indication became well-known. The UCPA (old Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 4; current Article 19, Paragraph 1, Item 3) provides a defense for such bona fide prior users, allowing them to continue their use under certain conditions. This existing defense was deemed sufficient protection for them.

- No Unfairness in Damages Claims: For claims seeking monetary damages, the UCPA (old Article 1-2; current provisions also link to tort principles) generally requires proof of intent or negligence on the part of the defendant. This fault requirement ensures that applying the specified timing for well-knownness will not lead to unjust outcomes in damages awards.

Application to the Earth Belt Case Facts:

Based on this legal framework, the Supreme Court found that the lower courts had erred in their approach:

- Even if Company X2's "Earth Belt" indication was not well-known by March 1979 (when Company Y launched its products), there was a distinct possibility that it could have become well-known at a later point in time relevant to the claims, particularly due to continued sales and advertising efforts by X2. The record indicated that X had indeed presented evidence of sales figures beyond March 1979.

- The lower courts, by focusing exclusively on the pre-Y launch period, had improperly restricted their assessment of well-knownness.

- Therefore, the part of the judgment concerning Company X2's claims (for both injunction and damages based on unfair competition) was overturned and remanded to the Sendai High Court for a new determination of whether well-knownness had been achieved at the relevant later dates (conclusion of oral arguments for the injunction, and the various times of Y's sales for the damages claim).

Dismissal of Mr. X1's Individual Appeal:

The Supreme Court, however, dismissed the appeal lodged by Mr. X1 (the individual inventor). The Court noted that, based on X1's own assertions, he himself was not directly engaged in the business of manufacturing or selling the "Earth Belt" products using the "Earth Belt" trademark; these activities were carried out by Company X2, to which X1 had granted an exclusive license. As such, the Court concluded that Mr. X1's own business interests were not directly harmed by Company Y's actions, and therefore, he lacked standing to bring the UCPA claim. The PDF commentary notes that this aspect concerning the standing of an individual licensor, as well as other issues in the case related to utility model compensation claims, have also been subjects of legal discussion, but the present analysis focuses on the well-knownness timing issue.

Significance of the Earth Belt Ruling: Bringing Clarity to a Contentious Point

The Supreme Court's decision in the Earth Belt case was highly significant for bringing clarity to a previously ambiguous area of unfair competition law.

- Resolving Inconsistent Lower Court Practice: Before this ruling, lower court decisions on the critical timing for establishing well-knownness had been inconsistent. Some, like the lower courts in the Earth Belt case itself and the earlier Hairbrush case (Osaka District Court, 1984), had insisted that well-knownness must exist before the defendant commenced its allegedly confusing activities, especially for injunctive relief. Other decisions, however, such as the ComputerLand case (Sapporo District Court, 1984), had granted injunctions based on well-knownness that was established by the time of the trial (conclusion of oral arguments), even if it wasn't necessarily present when the defendant first started their activities. The Earth Belt Supreme Court decision decisively settled this point.

- The "Columbus's Egg" Solution: The PDF commentary characterizes the Supreme Court's differentiated approach to timing—conclusion of oral arguments for injunctions, and time of infringing acts for damages—as a "Columbus's egg" solution. While perhaps seeming straightforward or even "a natural interpretation" from a civil procedure perspective (especially for injunctions being based on the current state of affairs), it was a novel and clarifying distinction in the context of UCPA well-knownness.

- Impact on Pleading and Proof Strategy: The ruling has important implications for how plaintiffs approach UCPA litigation. While a plaintiff might still opt to argue and prove that their mark was well-known before the defendant started their activities (this could be strategically advantageous, for instance, to counter any potential good faith prior use defense by the defendant), the Earth Belt decision clarifies that they are not strictly required to do so to obtain an injunction. They have the opportunity to continue building brand recognition and submit evidence of well-knownness up until the close of oral arguments in the fact-finding stages of the litigation. The PDF commentary mentions a post-Earth Belt Tokyo District Court case (Indian, 2003) where a plaintiff, having initially focused on proving well-knownness at the time the defendant started and failed on that specific point, was nevertheless granted an injunction based on well-knownness achieved six years later, seemingly an application of the Earth Belt principle.

The Debate: Defendant's Start Time vs. Conclusion of Oral Arguments for Injunctions

The Supreme Court's "conclusion of oral arguments" standard for injunctions was not without its critics. Arguments for using the defendant's activity start time as the benchmark included:

- Avoiding Instability: Allowing well-knownness to be judged at the end of what could be lengthy court proceedings might lead to situations where the status of a mark's recognition fluctuates, creating uncertainty.

- Preventing Abuse of Process: There were concerns that a plaintiff lacking initial well-knownness might deliberately prolong litigation while simultaneously intensifying advertising efforts, solely to meet the well-knownness threshold by the time oral arguments conclude. This could be seen as an unfair litigation tactic.

- Theoretical Consistency with Damages: Some argued that since damages claims often involve assessing the defendant's knowledge or culpability regarding the plaintiff's well-known mark, the same temporal focus (around the time of the defendant's actions) should apply to injunctions for logical consistency. This viewpoint often implies that causing confusion is an intentional act and that one cannot "confuse" with a mark that is not yet known.

However, the Supreme Court implicitly rejected these concerns, or found them outweighed by other considerations:

- Modern Litigation Speed: The PDF commentary suggests that concerns about litigation being unduly prolonged to achieve well-knownness have been somewhat mitigated by efforts to expedite intellectual property litigation in Japan.

- Objective Nature of "Likelihood of Confusion": The prevailing legal understanding in Japan is that the "likelihood of confusion" under UCPA Article 2(1)(i) is an objective assessment based on market realities. The defendant's subjective intent or awareness of potential confusion is generally not a required element for obtaining an injunction (though it is relevant for damages claims). Theories that tie the assessment of well-knownness for injunctions to the defendant's state of mind at the commencement of their activities do not align with this dominant objective interpretation.

Achieving Well-Knownness by Legitimate Means: A Postscript

An interesting epilogue to the Earth Belt saga, discussed in the PDF commentary, arose during the remanded proceedings at the Sendai High Court. While the focus here is on the timing of well-knownness, the subsequent High Court decision touched upon the means by which well-knownness is achieved. In the remanded case, Company X2's claim for damages was ultimately denied. The High Court found that Company X2 had used "PAT" markings on its products and in its advertising in a manner that could be misleading (potentially implying patent protection where none existed or was different). This was deemed to constitute false marking (a violation of patent law) and potentially an act causing misapprehension about quality or contents (under old UCPA Article 1(1)(v)). The High Court characterized these as "anti-moral acts" (反良俗的行為 - han ryōzokuteki kōi) and ruled that well-knownness achieved through such improper means could not form the basis for a damages claim under the UCPA, as the Act itself is designed to maintain fair competition. The Supreme Court later affirmed this aspect of the remanded High Court's judgment.

This raises a broader question: must well-knownness be achieved through entirely legitimate means to be protectable? The PDF commentary suggests that, generally, well-knownness is a factual state of market recognition. If that factual state exists, the means by which it was achieved (unless they render the indication itself deceptive or illegal) might be better addressed under separate legal doctrines (e.g., specific laws against false advertising, the general principle of abuse of rights) rather than by automatically negating the fact of well-knownness itself. However, the remanded Earth Belt decision indicates that courts will scrutinize conduct that taints the very goodwill being asserted.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Earth Belt case provided indispensable clarification on the critical temporal benchmarks for establishing "well-knownness" in Japanese unfair competition law. By differentiating the assessment timing for injunctive relief (conclusion of oral arguments) from that for damages claims (time of the defendant's specific acts), the Court established a flexible yet principled framework. This approach allows for the protection of commercial indications that achieve widespread recognition even during the course of litigation, aligning the UCPA's remedies with the evolving realities of the marketplace. While it places a continuous evidentiary burden on plaintiffs, it also ensures that the powerful remedies of unfair competition law are available once a genuine state of well-knownness, deserving of protection against source confusion, has been established. The case remains a cornerstone for understanding this fundamental element of unfair competition claims in Japan.