Timing is Everything: Japanese Supreme Court Rules on Revenue Recognition for Export Sales in the Otake Trading Case

Date of Judgment: November 25, 1993

Case Name: Corporate Tax Reassessment Invalidation Lawsuit (平成4年(行ツ)第45号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

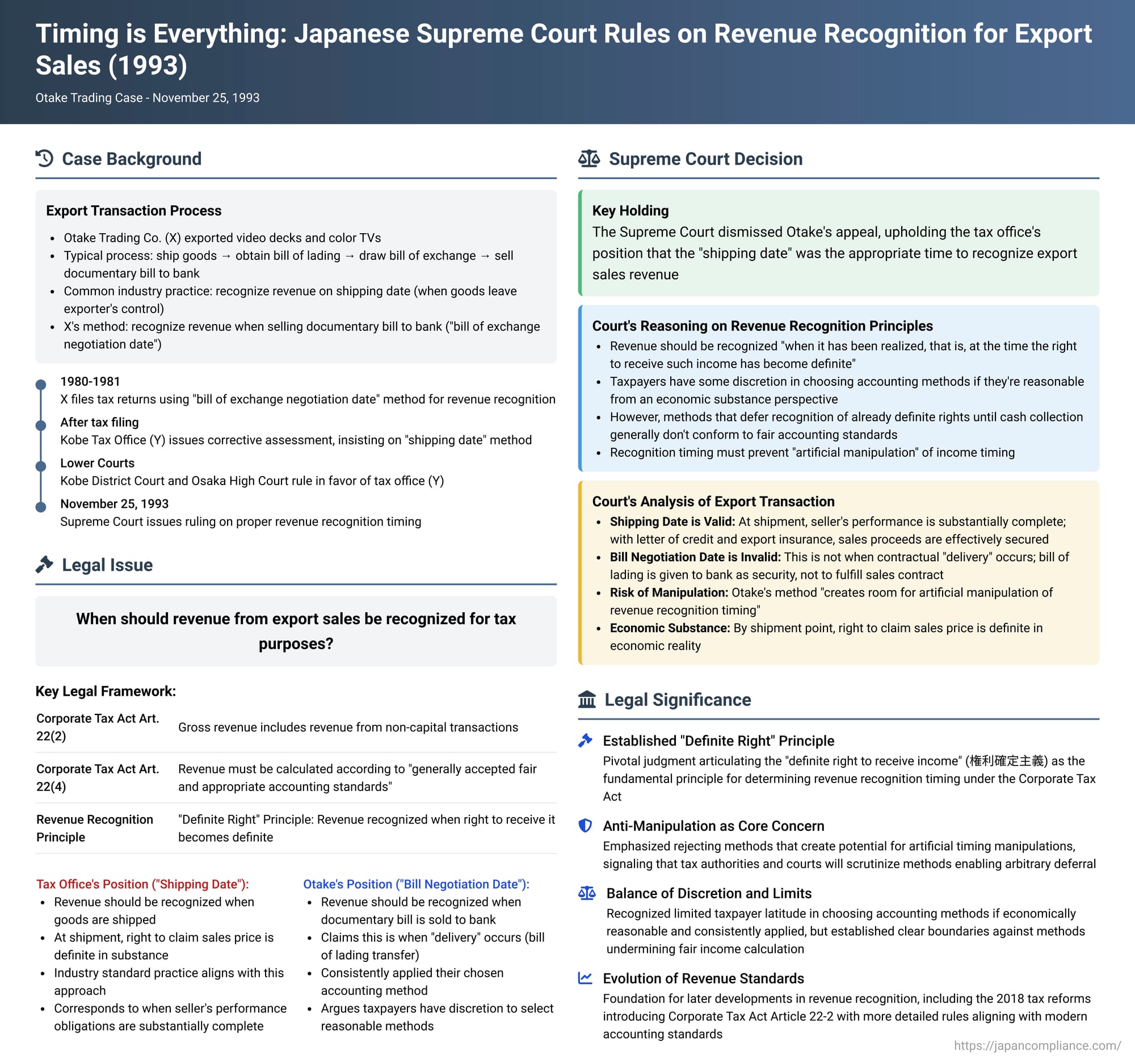

In a foundational decision for Japanese corporate tax law, the Supreme Court on November 25, 1993, in the case commonly known as the Otake Trading case, addressed the critical question of when revenue from export sales should be recognized for tax purposes. The ruling significantly clarified the application of the "definite right to receive income" principle and underscored the importance of preventing artificial manipulation of income timing. The Court ultimately upheld the tax authority's position, favoring the "shipping date basis" over the taxpayer's "bill of exchange negotiation date basis" for revenue recognition in the specific export transaction model presented.

The Export Transaction and Accounting Discrepancy

The appellant, X (formerly Otake Trading Co., Ltd.), was a company engaged in the export of goods such as video decks and color televisions. Its typical export transaction process involved several steps: X would ship the export goods, obtain a bill of lading from the carrier, draw a bill of exchange for the collection of the product price, and then attach the bill of lading and other shipping documents to this bill of exchange to create a documentary bill of exchange (荷為替手形 - ni-kawase tegata). X would then sell (discount) this documentary bill of exchange to its bank to receive payment.

At the time, due to the widespread use of letters of credit and export insurance systems, it was common for exporters, upon completing the shipment of goods, to be able to secure recovery of the sales proceeds by having their bank purchase the documentary bill of exchange. Reflecting this commercial reality, the "shipping date basis" (船積日基準 - funazumi-bi kijun)—recognizing revenue at the time the goods were shipped—was widely adopted in general accounting practice for export transactions.

However, X had consistently followed a different accounting method. It recognized revenue from its export transactions on the "bill of exchange negotiation date basis" (為替取組日基準 - kawase torikumi-bi kijun). X considered the delivery of goods to have occurred when it handed over the bill of lading to its bank during the process of the bank buying (negotiating) the documentary bill. X applied this method for calculating its taxable income in its corporate tax returns for the fiscal years ending March 1980 and March 1981.

The head of the competent tax office, Y (Kobe Tax Office Head), challenged X's accounting method. Y asserted that recognizing revenue based on the bill of exchange negotiation date did not conform to "generally accepted fair and appropriate accounting standards" (一般に公正妥当と認められる会計処理の基準 - ippan ni kōsei datō to mitomerareru kaikei shori no kijun). Instead, Y contended that the revenue from these export transactions should be recognized based on the shipping date. Consequently, Y issued a corrective assessment, recalculating X's taxable income and corporate tax liability for the two fiscal years in question. X disputed this assessment, and after losing in the lower courts (Kobe District Court and Osaka High Court), appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: Corporate Tax Act Article 22 and "Fair Accounting Standards"

The dispute centered on Article 22 of the Corporate Tax Act. Paragraph 2 of this article states that the amount to be included in gross revenue (ekikin) for each business year of a domestic corporation is, with certain exceptions, the amount of revenue from transactions other than capital transactions. Paragraph 4 of the same article mandates that this amount of revenue for the business year "shall be calculated in accordance with accounting standards generally accepted as fair and appropriate".

In its judgment, the Supreme Court laid out general principles for revenue recognition under these provisions:

- Adherence to Fair Accounting Standards: The timing of revenue recognition for a given fiscal year must comply with "generally accepted fair and appropriate accounting standards".

- Principle of Realization / Definite Right: According to these standards, revenue should generally be recognized "when it has been realized, that is, at the time the right to receive such income has become definite" (その収入すべき権利が確定した時 - sono shūnyū subeki kenri ga kakutei shita toki). This "definite right" principle is a cornerstone of income recognition in Japanese tax law.

- Taxpayer Discretion within Limits: The Court acknowledged that Article 22, paragraph 4 was intended to endorse a corporation's actual profit calculation methods as long as they do not contradict the Corporate Tax Act's aim of achieving a fair calculation of income. Therefore, determining the timing of when a right becomes definite should not be based solely on the single criterion of when the right becomes legally enforceable. If a corporation selects a specific revenue recognition standard from among those considered reasonable from the perspective of the economic substance of the transaction, and consistently applies that standard, then such accounting treatment should generally be accepted as valid for corporate tax purposes.

- Unacceptable Accounting Practices: However, the Court cautioned that accounting practices which recognize revenue before the right to it has become definite, or conversely, defer the recognition of an already definite right to receive income until cash is actually collected, are generally considered not to conform to fair and appropriate accounting standards.

The Supreme Court's Reasoning: Shipping Date Upheld, Negotiation Date Rejected

Applying these principles to X's export sales of inventory assets, the Supreme Court reached the following conclusions:

Why the Shipping Date Basis is Acceptable:

- Legal Perspective on Delivery: In export transactions where a bill of lading is issued (as was the case here), the complete delivery of the goods, which makes the seller's right to claim payment legally enforceable, occurs when the bill of lading is provided to the buyer. If one were to rely solely on this legal enforceability standard, recognizing revenue when the bill of lading is tendered to the buyer would be appropriate.

- Economic Substance at Shipment: However, the Court looked beyond strict legal form to the economic realities of modern export transactions. It found that by the time the goods are shipped, the seller's performance of their delivery obligations under the sales contract is, in substance, complete. Furthermore, as established in the facts, once shipment is completed, the seller can typically secure the sales proceeds by having a bank purchase (discount) the documentary bill of exchange. Therefore, the Court reasoned, the right to claim the sales price under the contract can be considered definite at the point of shipment. Consequently, recognizing revenue at the shipping date, based on this economic substance, is a rational accounting method and conforms to generally accepted fair and appropriate accounting standards. This method was also widely adopted in business practice.

Why X's Bill of Exchange Negotiation Date Basis is Unacceptable:

- Mischaracterization of Bill of Lading Transfer: X's method involved recognizing revenue when it delivered the bill of lading to its bank at the time the bank bought the documentary bill, asserting this act constituted the "delivery of goods". The Supreme Court found this premise to be flawed. The delivery of the bill of lading to the negotiating bank is not done to fulfill the seller's delivery obligation to the buyer under the sales contract; rather, it is provided to the bank as security for the bank's purchase of the bill of exchange. Therefore, this point in time cannot be considered the moment of contractual delivery of the goods.

- Deferral of Already Definite Income: The Court viewed X's method as effectively deferring the recognition of revenue from the sales price (which, as discussed above, could be considered definite at the shipment date) until the point of actual recovery of the sales proceeds' equivalent value through the bank's purchase of the documentary bill.

- Potential for Artificial Manipulation: Crucially, the Supreme Court stated that X's bill of exchange negotiation date basis "creates room for artificial manipulation of revenue recognition timing" (収益計上時期を人為的に操作する余地を生じさせる点において - shūeki keijō jiki o jin'iteki ni sōsa suru yochi o shōjisaseru ten ni oite).

- Non-Conformance with Fair Standards: Because of this potential for manipulation and the deferral of an already definite right, such an accounting treatment does not conform to generally accepted fair and appropriate accounting standards. Furthermore, the profit calculation resulting from such a method is "difficult to condone from the perspective of the Corporate Tax Act's aim of fair income calculation".

Given that the shipping date basis was found to be compliant with fair accounting standards and widely used in practice, the Supreme Court concluded that the tax office's corrective assessment based on this standard was lawful. X's appeal was therefore dismissed.

Significance and Implications

The Otake Trading case is a landmark decision in Japanese corporate tax law for several reasons:

- Establishment of the "Definite Right" Principle: It was a pivotal Supreme Court judgment that explicitly articulated the "definite right to receive income" (kenri kakutei shugi) as the fundamental principle for determining the timing of revenue recognition under the Corporate Tax Act.

- "Anti-Manipulation" as a Core Concern: The Court's strong emphasis on rejecting accounting methods that create the potential for artificial manipulation of income timing is a key takeaway. This signals that the tax authorities and courts will scrutinize methods that could lead to arbitrary deferral or acceleration of income.

- Balancing Taxpayer Choice and Tax Fairness: While the judgment acknowledged that taxpayers have some latitude in choosing accounting methods if they are economically reasonable and consistently applied, it clearly set a limit: this choice cannot extend to methods that undermine the principle of fair income calculation or allow for undue manipulation.

- Relationship with Accounting Principles: The decision sought to align tax law's "definite right" principle with the "realization principle" found in Japanese corporate accounting standards (though, as some commentators noted, the Court did not extensively elaborate on the specific content of "realization").

- Impact of Dissenting Opinions: It is noteworthy that two Supreme Court justices issued dissenting opinions. They argued that X's bill of exchange negotiation date basis should also be considered an acceptable accounting method. One dissent, for instance, focused on interpreting "generally accepted fair and appropriate accounting standards" by reference to Commercial Code provisions applicable to corporate accounting, suggesting that since the seller (X) completed all necessary actions for delivering the goods to the buyer when it handed the bill of lading to its bank, and payment became certain at that point, this method was reasonable and compliant. The existence of these dissents underscores the complexity of the issue and the different perspectives on what constitutes a "fair and appropriate" standard.

Subsequent Developments

It is important to note that since this 1993 judgment, Japan's framework for revenue recognition has continued to evolve. Notably, the 2018 tax reforms saw the introduction of Article 22-2 into the Corporate Tax Act. This article provides more detailed general rules for the timing of revenue recognition, such as the delivery basis for the sale of goods and the service provision basis for services, partly in response to developments in accounting standards, including "Revenue Recognition Accounting Standard" (ASBJ Statement No. 29). While aiming for greater harmonization with accounting practices, these new provisions also explicitly acknowledge that specific tax law overrides ("別段の定め" - betsudan no sadame) will take precedence.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in the Otake Trading case remains a crucial precedent in Japanese corporate tax law. It firmly established the "definite right to receive income" as the guiding principle for revenue recognition timing and highlighted the critical importance of preventing artificial manipulation that could undermine fair income calculation. By upholding the shipping date as an appropriate basis for recognizing revenue from the export sales in question—a method grounded in economic substance and widely accepted in practice—the Court provided essential clarity while also signaling the limits of taxpayer discretion in choosing accounting methods for tax purposes.