Time-Barred But Not Defenseless: Japan's Supreme Court on Invalidity and Abuse of Rights in the Emax Trademark Case

Judgment Date: February 28, 2017

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 27 (Ju) No. 1876 (Main Claim for Injunction, etc. under Unfair Competition Prevention Act; Counterclaim for Injunction, etc. for Trademark Infringement)

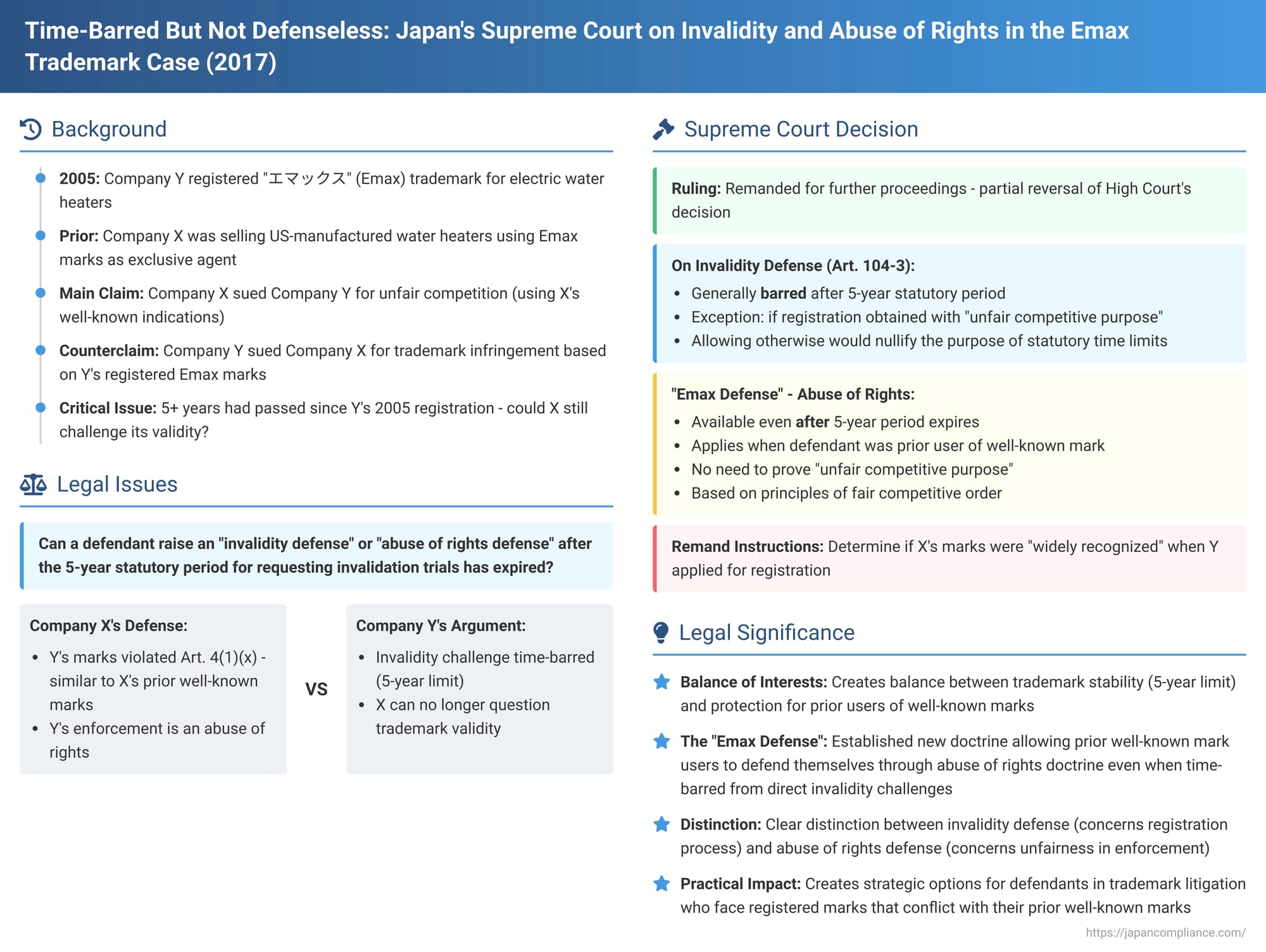

The "Emax" case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2017, is a significant judgment that navigates the complex interplay between statutory time limits for challenging trademark registrations and the defenses available in trademark infringement lawsuits. The Court addressed two critical issues: first, the permissibility of raising an "invalidity defense" after the five-year statutory period for seeking an invalidation trial has lapsed; and second, the viability of an "abuse of rights" defense under similar time-barred circumstances, particularly when the challenged trademark registration conflicts with the defendant's prior well-known mark. This decision has profound implications for both trademark owners and users in Japan.

The Emax Dispute: Water Heaters and Conflicting Claims

The case involved a dispute over the "Emax" brand used for electric instant water heaters.

- Company X's Main Claim (Unfair Competition): Company X (the appellee before the Supreme Court) was the exclusive sales agent in Japan for electric water heaters ("the Heaters") manufactured by a U.S. company, Company A. Company X had been using several trademarks, including "エマックス" (Emax in Katakana), "EemaX," and "Eemax" (collectively, "X's Used Marks"), to market and sell these Heaters in Japan. When Company Y began independently importing the same Heaters from Company A and selling them in Japan using marks identical to X's Used Marks, Company X filed a lawsuit against Company Y. The main claim was for unfair competition under Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA), Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1 (prohibiting the use of another's well-known indication of goods or business in a manner that causes confusion), seeking an injunction and damages.

- Company Y's Counterclaim (Trademark Infringement): Company Y (the appellant before the Supreme Court) responded with a counterclaim. Company Y asserted that it owned Japanese trademark registrations for "エマックス" (in standard Katakana characters, registered in 2005) and another related "Emax" mark (registered in 2010) (collectively, "Y's Registered Marks"), both designating electric water heaters. Company Y alleged that Company X's continued use of "Emax" and similar marks constituted an infringement of Y's Registered Marks and sought an injunction and damages against Company X.

- Company X's Defense to the Counterclaim: In response to Company Y's infringement counterclaim, Company X argued that Y's Registered Marks should not have been granted in the first place. Specifically, X contended that Y's marks were unregistrable under Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 10 of the Japanese Trademark Law. This provision prohibits the registration of a trademark that is identical or similar to another person's trademark which is widely recognized among consumers as indicating their goods or services, if used on similar goods or services, and is likely to cause confusion. Company X asserted that its own "Emax" marks were already well-known at the time Company Y applied for its registrations.

- The Critical Time-Limit Issue: A key complication arose: for Company Y's 2005 "エマックス" registration, more than five years had passed from its registration date until the point in the litigation where Company X formally raised the Article 4(1)(x) invalidity argument. During those five years, Company X had not filed a request with the Japan Patent Office (JPO) for an invalidation trial based on Article 4(1)(x). Under Article 47, Paragraph 1 of the Trademark Law, there is generally a five-year statutory period (除斥期間 - joseki kikan, or period of repose) for requesting an invalidation trial on grounds such as an Art. 4(1)(x) violation (unless the challenged registration was obtained for an "unfair competitive purpose").

- Prior Litigation History: The relationship between Company X and Company Y was not new to the courts. They had previously entered into a sales agency agreement for the Heaters, which later ended amidst disputes. This led to earlier litigation that concluded with a court settlement in which Company Y, among other things, pledged not to use the "Emax" product name.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the Oita District Court (first instance) and the Fukuoka High Court (appellate instance) had partially found in favor of Company X on its main unfair competition claim, acknowledging that X's Used Marks were indeed well-known. Crucially, regarding Company Y's trademark infringement counterclaim, both lower courts accepted Company X's defense. They ruled that Y's Registered Marks were, in fact, invalid under Article 4(1)(x) and that Company Y therefore could not enforce these rights against Company X. This was based on the "invalidity defense" provided by Article 39 of the Trademark Law (which applies mutatis mutandis Article 104-3, Paragraph 1 of the Patent Law). This defense allows a party accused of infringement to argue that the patent (or trademark) right being asserted against them should be invalidated. The lower courts dismissed Company Y's counterclaim.

Company Y appealed this dismissal of its counterclaim to the Supreme Court, focusing on whether Company X could still raise the invalidity argument after the five-year statutory period had expired.

The Supreme Court's Twin Rulings on Defenses After the Repose Period

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's decision (specifically concerning the dismissal of Y's counterclaim) and remanded that part of the case for further proceedings. The Court's judgment drew a critical distinction between asserting a direct "invalidity defense" under Patent Law Art. 104-3 and asserting an "abuse of rights" defense.

1. The Invalidity Defense (Art. 104-3) After the Five-Year Repose Period:

The Supreme Court addressed whether an alleged infringer can assert the invalidity of a trademark registration (based on a violation of Article 4(1)(x)) as a defense in an infringement lawsuit after the five-year statutory period for initiating an invalidation trial on that ground has passed.

- General Rule – Defense Barred: The Court held that, as a general rule, if a request for an invalidation trial based on Article 4(1)(x) has not been filed with the JPO within five years from the date of the trademark's registration, the party accused of infringement cannot thereafter assert the existence of that Article 4(1)(x) invalidity ground as a defense under Patent Law Article 104-3, Paragraph 1 in the infringement lawsuit.

- Crucial Exception – "Unfair Competitive Purpose": This general rule does not apply if it can be shown that the trademark registration in question was obtained by the trademark owner for an "unfair competitive purpose" (不正競争の目的 - fusei kyōsō no mokuteki). If such a purpose is established, the invalidity defense can still be raised even after five years.

- Rationale for the General Rule:

- Statutory Repose (Article 47(1)): The Trademark Law's Article 47(1) establishes a five-year period of repose for challenging registrations on certain grounds, including Article 4(1)(x). The purpose of this repose period is to bring stability and finality to trademark rights once a certain amount of time has passed without challenge, thereby protecting the existing, ongoing legal status created by the registration (the Court cited its 2005 RUDOLPH VALENTINO case decision on this point).

- Wording of Patent Law Art. 104-3(1): This provision (applied to trademarks) allows a defense if the trademark registration "is recognized as one that should be invalidated by an invalidation trial." The Supreme Court reasoned that if an invalidation trial can no longer be requested due to the expiry of the repose period, then there is logically no room for a court in an infringement action to recognize the registration as one that "should be invalidated" on those time-barred grounds.

- Preserving the Repose Period's Intent: Allowing the Art. 104-3 invalidity defense to be raised indefinitely, even after the five-year period for an invalidation trial has passed, would effectively nullify the purpose of the statutory repose period established by Article 47(1).

2. The "Emax Defense" – Abuse of Rights for Prior Well-Known Mark Users:

Despite generally barring the direct invalidity defense after five years, the Supreme Court carved out a distinct path for defendants who were users of a prior well-known mark.

- Underlying Purpose of Article 4(1)(x): The Court noted that Article 4(1)(x) aims to prevent the registration of trademarks that conflict with another person's prior well-known mark. This serves two goals: preventing confusion as to the source of goods/services and balancing the interests of the established user of the well-known mark against those of the new trademark applicant.

- The Abuse of Rights Principle in This Context: The Supreme Court reasoned that if a registered trademark was, in fact, registered in violation of Article 4(1)(x) (i.e., at the time of its application, it was confusingly similar to a mark already widely recognized by consumers as indicating another party's goods or services), then for the owner of such an improperly registered trademark to assert it against the very party whose prior well-known mark it conflicts with would, absent special circumstances, constitute an abuse of rights (権利濫用 - kenri ranyō). Such enforcement would harm one of the fundamental objectives of trademark law, which is the maintenance of an objectively fair competitive order (the Court referenced its 1990 Popeye Muffler case decision).

- Permissibility of the Abuse of Rights Defense After Five Years: Crucially, the Supreme Court held that an alleged infringer who is the user of such a prior well-known mark can assert this "abuse of rights" defense even after the five-year period for filing an invalidation trial under Article 4(1)(x) has expired. The Court stated that allowing this specific abuse of rights defense, even after the repose period for invalidation trials, does not negate the purpose of Article 47(1).

- Rationale for Allowing the Abuse Defense Post-Repose: The judicial commentary accompanying the decision explains that the repose period under Article 47(1) is primarily intended to protect a registered trademark from challenges by third parties generally after a certain time. However, allowing the owner of an improperly registered mark to enforce it against the specific party whose established, well-known mark was effectively preempted or usurped by that registration would be fundamentally unfair and contrary to the overarching goals of trademark law. The abuse of rights defense in this context is thus tailored to the user of the prior well-known mark.

- Scope of this "Emax Defense": This particular abuse of rights defense (now sometimes dubbed the "Emax defense") can be raised by the prior well-known mark user regardless of whether the challenged trademark registration was obtained with an "unfair competitive purpose" or not. This makes it distinct from, and potentially easier to invoke than, the exception to the time bar for the direct invalidity defense.

Application to the Emax Case and Remand:

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in allowing the direct invalidity defense under Patent Law Art. 104-3 for Y's 2005 registration without first determining whether that registration had been obtained by Y for an "unfair competitive purpose." If no such purpose was found, the direct invalidity defense should have been barred by the five-year time limit.

However, the Supreme Court also recognized that Company X's arguments in the High Court could be construed as including an assertion of the newly articulated "abuse of rights" defense (i.e., that Y was abusively asserting its registered "Emax" marks against X, whose own "Emax" marks were allegedly well-known prior to Y's applications).

The Supreme Court determined that the High Court had not conducted a sufficient factual inquiry into whether X's Used Marks were indeed "widely recognized among consumers" as indicating X's goods or services at the respective times Company Y had filed its trademark applications. The evidence presented regarding X's advertising expenditure and sales figures was deemed insufficient by the Supreme Court to automatically conclude that X's marks had achieved nationwide widespread recognition by those critical dates.

Therefore, the Supreme Court remanded the counterclaim portion of the case to the Fukuoka High Court for further proceedings to specifically determine:

- Concerning the direct invalidity defense (Patent Law Art. 104-3) for Y's 2005 registration: Was this registration obtained by Y with an "unfair competitive purpose"? (If not, the defense would be time-barred).

- Concerning the "abuse of rights" defense (for all of Y's registered marks): Were Company X's Used Marks indeed widely recognized as indicating X's goods/services at the times Company Y filed for its respective trademark registrations? If this prior wide recognition is established, then, absent special circumstances, Company Y's assertion of its trademark rights against Company X would constitute an abuse of rights.

Justice Yamazaki's Supplementary Opinion:

A supplementary opinion by Justice Yamazaki concurred with the majority but added that the "abuse of rights" determination is always a holistic one, based on all circumstances of the case. The "Emax defense" (assertion of rights against a prior well-known mark user as abusive) represents one categorized or typified instance of such abuse. Even if this specific categorized defense is not met, a court could still find an abuse of rights based on other factors, such as the contentious history and prior litigation between the parties, which Company X had also raised.

Navigating the Interplay: Why an Abuse Defense Might Succeed When an Invalidity Defense is Time-Barred

The Emax case is pivotal because it clarifies that even when a direct challenge to a trademark's validity based on certain grounds (like Art. 4(1)(x)) is time-barred by the five-year repose period, a defendant (particularly one who used a well-known mark prior to the plaintiff's registration) is not left without recourse. The "abuse of rights" doctrine provides an alternative avenue for defense.

- The "Emax Defense" is More Accessible in Some Ways:

- It is available even after the five-year repose period has passed for an invalidation trial.

- It does not require the defendant to prove that the trademark owner obtained their registration with an "unfair competitive purpose," which can be a difficult evidentiary burden. Proving one's own prior mark's widespread recognition might be comparatively easier.

- The "Emax Defense" is Specific: It is available only to the party whose prior well-known mark is being infringed upon by the later, improperly registered mark. It's not a general defense available to any third party.

- "Special Circumstances" Can Negate the Abuse Defense: The Court did allow for "special circumstances" that might permit the trademark owner to enforce their right even against a prior well-known user. Such circumstances could include, for example, if the prior well-known user themselves is acting with an unfair competitive purpose.

Critiques and Scholarly Discussion

The creation of the "Emax defense" has been a subject of considerable academic discussion:

- Rationale for Overriding Repose Period: While the Court stated that allowing this specific abuse defense does not negate the general purpose of the Article 47(1) repose period (because the mark remains valid against other third parties), some scholars question the clarity of the legal reasoning that allows the policy behind Article 4(1)(x) (protecting prior well-known marks) to effectively override the policy of the repose period specifically for this class of defendants.

- Relationship with Prior Use Rights (Art. 32): A significant point of critique is the relationship between the "Emax defense" and the statutory right of prior use (先使用権 - sen shiyōken) under Trademark Law Article 32. The right of prior use grants a defense to a party who was using a mark (and had achieved some recognition for it) before another party filed for an identical or similar mark. However, prior use rights are often limited in scope (to the actual extent of use) and can be subject to requirements to add distinguishing indications to prevent confusion. The "Emax defense," as formulated, potentially offers broader protection than prior use rights without these limitations. Critics argue that this new defense might undermine the carefully balanced regime of prior use rights. The Supreme Court, however, seems to have implicitly considered the existing prior use right system as potentially insufficient for robustly protecting users of marks that have achieved widespread recognition.

Conclusion

The Emax Supreme Court decision makes a significant contribution to Japanese trademark jurisprudence by delineating the boundaries of defenses available against trademark infringement claims, especially when statutory time limits for challenging a registration's validity have expired. The ruling confirms that the direct "invalidity defense" under Patent Law Article 104-3 is generally unavailable after the five-year repose period for grounds like Article 4(1)(x) of the Trademark Law, unless the registration was obtained with an unfair competitive purpose. More innovatively, the Court established the "Emax defense," a specific type of "abuse of rights" defense, available to users of prior well-known marks even after the repose period has passed, irrespective of the registrant's subjective intent. This defense underscores the principle that the enforcement of trademark rights must align with the broader objectives of maintaining fair competitive order and protecting established goodwill, offering a crucial avenue for relief to those whose recognized marks are effectively usurped by later registrations. The case highlights the dynamic nature of trademark law, where equitable considerations can temper the strict enforcement of registered rights.