Third-Party Property Attached from Bankrupt: Supreme Court on Proper Remedy After Bankruptcy Commencement

Date of Judgment : January 29, 1970 (Showa 45)

Case Name : Third-Party Objection Suit

Court : Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

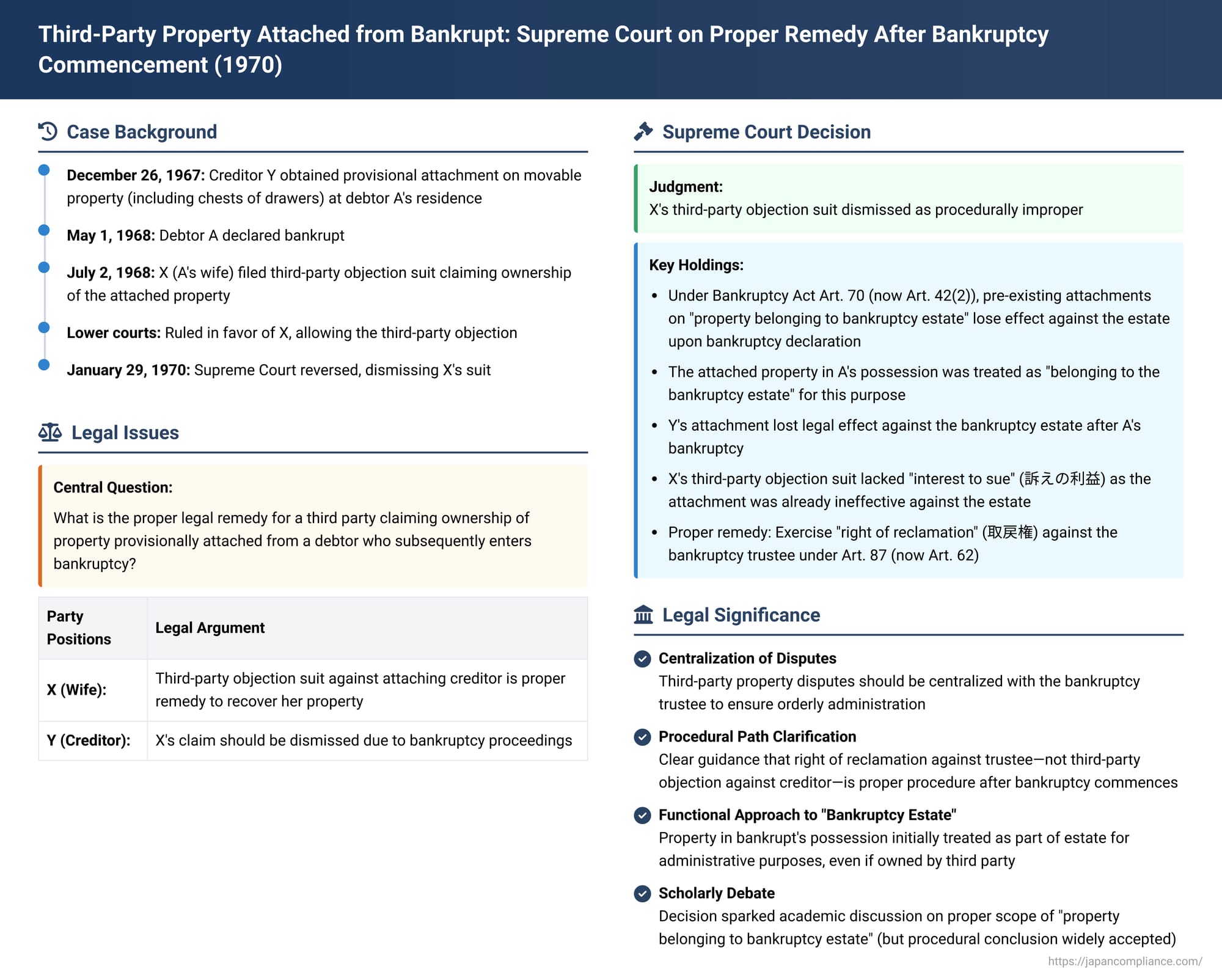

This blog post examines a 1970 Supreme Court of Japan decision. The case clarifies the appropriate legal procedure for a third party who claims ownership of movable property that was provisionally attached while in the possession of a debtor, when that debtor subsequently enters bankruptcy.

Facts of the Case

Creditor Y (the appellant before the Supreme Court) had obtained a provisional attachment order (仮差押決定 - kari-sashiosae kettei) against a debtor named A . Pursuant to this order, on December 26, 1967, an execution officer effected a provisional attachment on three movable items, including chests of drawers, located at A's residence .

Subsequently, on May 1, 1968, A was declared bankrupt (an event corresponding to a "bankruptcy proceedings commencement decision" under current Japanese law) . Following this, X (the respondent before the Supreme Court), who was A's wife, filed a "third-party objection suit" (第三者異議の訴え - daisansha igi no uttae). In this suit, X asserted that the attached movable items were her own personal property and demanded that Y's provisional attachment be prohibited from being levied against these items .

Lower Court Rulings

- The court of first instance (Nagoya District Court) ruled in favor of X, recognizing her claim and presumably allowing the objection to the attachment .

- The High Court (Nagoya High Court) affirmed the first instance decision . The High Court reasoned that since the attached items were found to be X's property, they would not become part of A's bankruptcy estate merely because A (X's husband and the debtor in possession) was declared bankrupt . Therefore, Y's provisional attachment, which targeted A's assets, was deemed wrongful as against X's ownership rights .

Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court reversed the judgments of both the High Court and the court of first instance. It ultimately dismissed X's third-party objection suit as procedurally improper .

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Effect of Bankruptcy on Pre-existing Attachments:

The Court noted the factual sequence: Y had provisionally attached the items from debtor A on December 26, 1967, and A was subsequently declared bankrupt on May 1, 1968 .

Under Article 70 of the old Bankruptcy Act (which corresponds to Article 42, Paragraph 2 of the current Bankruptcy Act), when a debtor is declared bankrupt, any pre-existing attachments or provisional attachments levied on "property belonging to the bankruptcy estate" (破産財団に属する財産 - hasan zaidan ni zokusuru zaisan) lose their effect against the bankruptcy estate .

The Supreme Court determined that, for the purposes of this provision, the attached items in this case were to be treated as having become "property belonging to the bankruptcy estate" upon A's bankruptcy declaration . - Provisional Attachment Rendered Ineffective:

As a consequence of A's bankruptcy and the application of Article 70, Y's provisional attachment on these items lost its legal effect against the bankruptcy estate . - Lack of "Interest to Sue" for the Third-Party Objection:

X filed her third-party objection suit on July 2, 1968, after A's bankruptcy declaration and thus after Y's provisional attachment had already lost its effect against the bankruptcy estate . A third-party objection suit is a remedy designed to seek the exclusion or prohibition of an existing, effective execution or attachment against property that the third party claims to own. Since Y's provisional attachment was no longer effective against the (now controlling) bankruptcy estate, X's lawsuit seeking to prevent this (already ineffective against the estate) attachment lacked a legitimate "interest to sue" (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki) . Such a suit was therefore procedurally improper and should be dismissed . - Correct Procedural Path for the Third-Party Claimant:

The Supreme Court clarified that if X wished to assert her ownership over the items and secure their return, her proper course of action was not to sue the attaching creditor Y (whose attachment was now moot in the bankruptcy context) . Instead, X should have exercised her "right of reclamation" (取戻権 - torimodoshi-ken) against A's bankruptcy trustee, pursuant to Article 87 of the old Bankruptcy Act (which corresponds to Article 62 of the current Bankruptcy Act) . This right allows a third party to recover property that belongs to them but is in the possession of the bankrupt and has been included in the bankruptcy estate.

The Supreme Court therefore quashed the lower court judgments and dismissed X's suit.

Commentary and Elaboration

1. The Apparent Contradiction: Third-Party Property and the "Bankruptcy Estate"

A key point of discussion arising from this decision revolves around the Supreme Court's treatment of the attached items. If the movable property genuinely belonged to X (the bankrupt's wife) and not to A (the bankrupt), one might intuitively argue that it should not be considered "property belonging to the bankruptcy estate" of A. If so, Article 70 of the old Bankruptcy Act (now Article 42, Paragraph 2), which causes attachments on estate property to lose effect, arguably should not have applied to an attachment on X's separate property. This was, in essence, the reasoning of the High Court.

2. The Supreme Court's Functional Approach

However, the Supreme Court took a different, more functional approach. It appears to have reasoned that because the movable items were in A's possession at A's residence when they were attached as A's ostensible property, upon A's bankruptcy, these items came under the administrative purview of A's bankruptcy trustee, at least initially. From the perspective of the bankruptcy proceeding and the administration of assets found with the bankrupt, Y's specific provisional attachment on these items then lost its efficacy against the bankruptcy estate due to Article 70.

Since the attachment was no longer an effective encumbrance that the trustee had to contend with from Y, a lawsuit by X against Y to lift that specific (now ineffective against the estate) attachment became pointless. The real dispute over ownership and possession needed to be resolved with the party now in control or asserting administrative rights over the assets – the bankruptcy trustee.

3. Procedural Standing and the Role of the Trustee

The commentary provided with the case suggests that the Supreme Court's conclusion is supported from a procedural or functional viewpoint concerning "standing to be sued" (当事者適格 - tōjisha tekikaku). In bankruptcy, for assets that were possessed and managed by the bankrupt prior to bankruptcy (thus creating an appearance that they belong to the debtor's estate), it is generally considered desirable to centralize legal disputes concerning such assets with the bankruptcy trustee. This approach promotes orderly administration and prevents piecemeal litigation with various creditors over assets that might form part of the estate. Therefore, directing X to pursue a right of reclamation against the trustee, rather than continuing a third-party objection suit against the creditor Y whose attachment had become ineffective against the estate, aligns with this principle of centralized dispute resolution in bankruptcy.

4. Scholarly Debate on the Scope of "Property Belonging to the Bankruptcy Estate"

While the outcome (dismissal of X's suit against Y and redirection to a reclamation claim against the trustee) is generally supported by commentators, the Supreme Court's premise that third-party property in the bankrupt's possession becomes "property belonging to the bankruptcy estate" for the purpose of applying Article 70 (now Article 42, Paragraph 2) has been questioned. Some scholars argue that the phrase "property belonging to the bankruptcy estate" in this context should ideally refer only to property that actually belongs to the bankrupt (often termed the "actual estate" or 現有財団 - genyū zaidan). If X's property was never truly A's, then Y's attachment on it might not have "lost effect" under Article 70 in a way that negates X's fundamental ownership rights vis-à-vis Y, even if the enforcement of that attachment against the assets now under the trustee's control was stayed or nullified.

However, despite this doctrinal debate about the precise scope of "property belonging to the bankruptcy estate," the Supreme Court's ultimate procedural directive—that X should assert her ownership through a reclamation claim against the bankruptcy trustee—is widely seen as the correct and practical way to resolve such ownership disputes once bankruptcy proceedings have commenced over the possessor of the disputed assets.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1970 decision provides important guidance on the procedural path for third parties claiming ownership of assets that were provisionally attached while in the possession of a debtor who subsequently enters bankruptcy. The Court held that once bankruptcy proceedings commence, a pre-existing provisional attachment on assets that come under the trustee's administration loses its effect against the bankruptcy estate. Consequently, a third-party objection suit filed by the true owner against the attaching creditor to lift that (now ineffective against the estate) attachment lacks a legitimate interest to sue. Instead, the proper remedy for the third-party owner is to exercise a "right of reclamation" against the bankruptcy trustee to recover their property from the bankruptcy estate. This ruling emphasizes the central role of the bankruptcy trustee in managing and resolving claims over assets found in the bankrupt's possession, thereby ensuring an orderly administration process.