Theft of Your Own Property? A Japanese Ruling on Possession, Ownership, and Self-Help

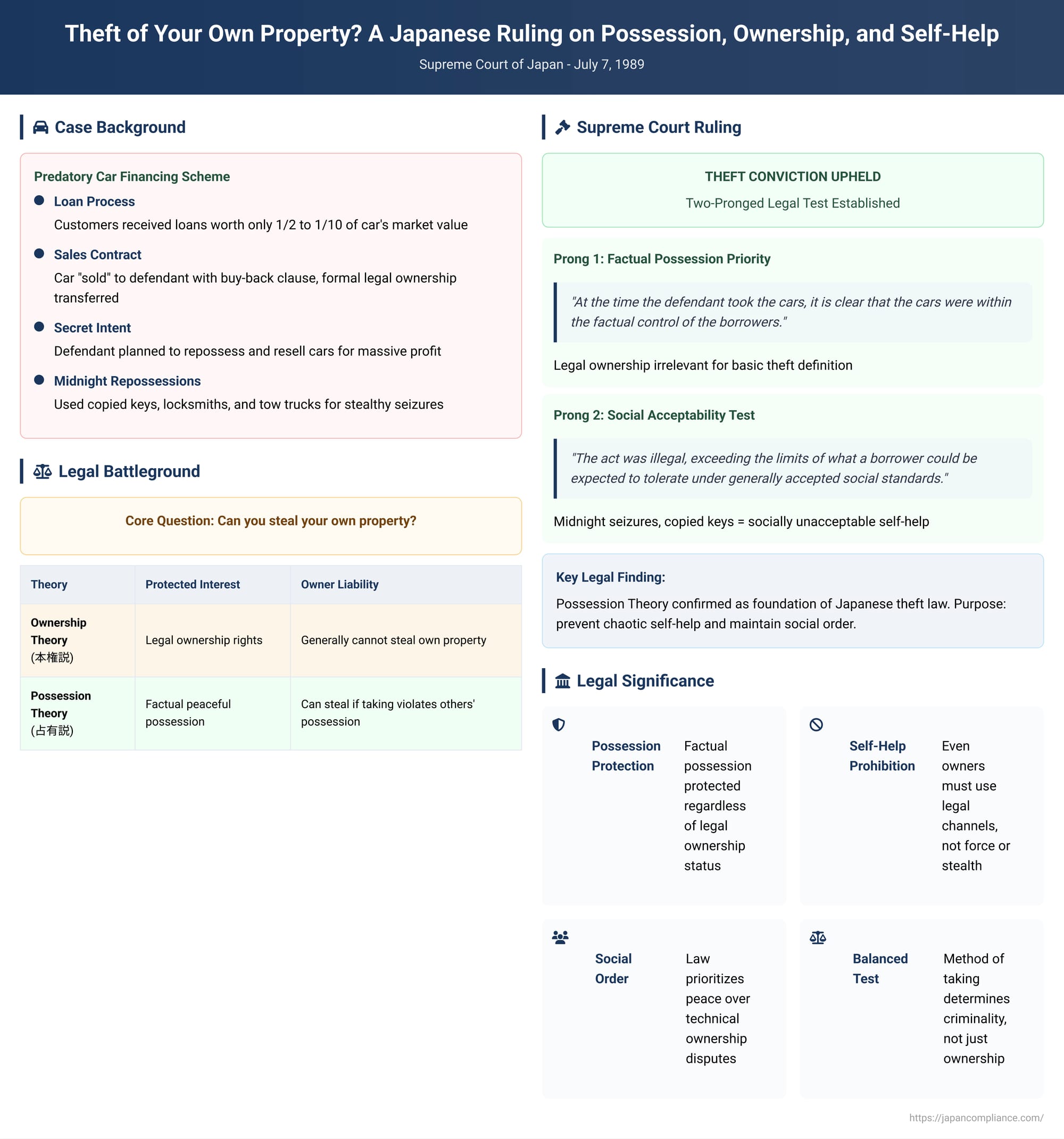

Can you be convicted of stealing something that you legally own? This question, which challenges the common-sense understanding of theft, lies at the heart of a fundamental debate in property law: does the crime of theft protect legal ownership, or does it protect the simple, factual state of peaceful possession? On July 7, 1989, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision that addressed this issue head-on in the context of a predatory car financing scheme, establishing a crucial two-part test that continues to define the boundaries of theft in Japan.

The ruling affirmed that taking property from someone else's peaceful possession can be theft—even if you are the legal owner. More importantly, it clarified that the ultimate criminality of such an act depends on whether the method of taking was socially tolerable or an illegal act of self-help.

The Facts: The Car Financier and the Midnight Repossessions

The case involved a defendant who ran a car financing business that operated through "sales agreements with a buy-back clause." The scheme worked as follows:

- The Loan: A customer seeking a loan would be offered an amount worth only a fraction—from one-half to as little as one-tenth—of their car's actual market value.

- The Contract: To secure this loan, the customer was required to sign a contract that, on paper, "sold" their car to the defendant. This contract formally transferred legal ownership and the right of possession to the defendant. It included a clause allowing the customer to "buy back" the car by a certain deadline if they repaid the loan plus a high rate of interest. If they failed, the contract stipulated that the defendant could dispose of the car at will.

- The Reality: Despite the contract's formal terms, it was an "obvious premise" between the parties that the borrower would keep the car and continue to use it as their own. The defendant, however, secretly intended to repossess and resell the cars immediately if a borrower was even slightly late with a payment, as reselling the undervalued cars was far more profitable than collecting the loan interest. To facilitate this, he did not provide customers with a copy of the contract they had signed.

- The Repossessions: When a borrower missed a deadline—and in some cases, even before the deadline had passed—the defendant's agents would go to the borrower's home or workplace, often in the middle of the night. They would use stealthy methods to take the cars without any notice or confrontation. This included using spare keys that had been secretly copied when the original keys were entrusted to them for a supposed "inspection," having a locksmith make new keys on the spot, or simply using a tow truck to haul the vehicle away. The repossessed cars were then quickly resold.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of theft. He appealed, arguing that since he was the legal owner of the cars under the sales agreements, he could not be guilty of stealing his own property. The lower courts disagreed, with the High Court noting that the exploitative contract was likely invalid and that the borrowers' possession was "still a legally protectable interest."

The Legal Battleground: Ownership vs. Possession

The defendant's argument brought a classic legal debate to the forefront: what is the primary "protected legal interest" (hogo hōeki) of the crime of theft?

- The Ownership Theory (Honken-setsu): This is the traditional and intuitive view. It holds that theft law protects the true, underlying legal right to property, such as ownership. Under this theory, it is logically difficult for an owner to "steal" their own property. This was the prevailing view in Japan before World War II.

- The Possession Theory (Sen'yū-setsu): This is the more modern view. It argues that theft law protects the factual state of peaceful possession, regardless of who holds the ultimate legal title. The primary goal of this theory is to maintain social order by prohibiting "self-help." It forces individuals, including legal owners, to use proper legal channels (like the courts) to resolve property disputes rather than resorting to unilateral force or stealth to reclaim property. Post-war Japanese case law had been seen as shifting towards this theory.

The Supreme Court's Two-Pronged Ruling

The Supreme Court upheld the defendant's theft conviction, articulating a clear, two-part test that has become a landmark in Japanese property crime jurisprudence.

Prong 1: The Primacy of Factual Possession

First, the Court focused on the physical reality of the situation, not the paper contract. It stated:

"At the time the defendant took the cars, it is clear that the cars were within the factual control of the borrowers."

Because the cars were in the borrowers' possession, the Court found that the defendant's act of taking them satisfied the basic definition of theft under the Penal Code, which criminalizes the taking of property from "the possession of another" (Article 242). This part of the ruling was a strong affirmation of the Possession Theory. The Court made clear that for the purpose of defining the initial act of theft, factual possession trumps legal ownership.

Prong 2: The Illegality of the Taking

Second, the Court did not stop there. It went on to evaluate the manner of the repossession. The Court added a crucial second layer to its analysis:

"Moreover, the act was illegal, exceeding the limits of what a borrower could be expected to tolerate under generally accepted social standards."

This finding was critical. It established that violating another's possession is not automatically a criminal theft in every circumstance. The wrongfulness of the act must also be considered. Here, the defendant's methods—using secretly copied keys, acting in the middle of the night without notice, and using tow trucks—were deemed socially unacceptable and illegal forms of self-help, not a legitimate exercise of a right.

Analysis and Implications

The 1989 decision is understood as the Supreme Court's definitive confirmation of the modern Possession Theory as the foundation of Japanese theft law. The primary purpose of the law is to protect social peace by preventing individuals from taking matters into their own hands.

However, the ruling's second prong adds a crucial layer of nuance. By assessing the "illegality" and social acceptability of the repossession, the Court left the door open for an owner to reclaim their property without committing theft, provided they do so in a reasonable manner. For example, openly asking for the return of one's property might be acceptable, whereas breaking into a home to retrieve it would be an illegal act of self-help and thus a theft.

Intriguingly, some legal analysis suggests the defendant could have been convicted even under a modified version of the Ownership Theory. In a secured transaction like this, Japanese civil law often implies a relationship of "simultaneous performance." The borrower must return the collateral, but the lender has a corresponding duty to properly liquidate it and return any surplus value. Since the defendant had a clear intention to simply seize the cars for his own massive profit without fulfilling this duty, the borrowers had a legal right to refuse to hand over possession. From this perspective, their possession was legally protected even against the owner, making the defendant's actions a theft regardless of which theory is applied.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1989 decision in this predatory lending case serves as a powerful illustration of the principles underlying Japanese theft law. It firmly established that the law's primary goal is to protect peaceful, factual possession in order to prevent chaotic self-help, even by a legal owner.

The ruling offers two clear takeaways. First, in the eyes of the law, violating someone's peaceful control over an object is the starting point for theft. Second, whether an owner's act of repossession crosses the line into a criminal act depends on the methods used. By employing stealth and socially unacceptable means, the defendant in this case transformed himself from a creditor into a common thief. The decision stands as a stark warning that even with a contract in hand, resorting to illegal self-help to reclaim property is a path to a criminal conviction.