The Witness as Evidence: How Japan's High Court Ruled on the Crime of Hiding a Witness

What is "evidence" in a criminal case? The term typically conjures images of physical objects: a weapon, a signed contract, a strand of hair, or a digital file. But what if the most crucial piece of evidence is not a thing, but a person? If a suspect, in a desperate attempt to derail an investigation, physically hides a key witness to prevent them from speaking to the police, have they committed the crime of "Concealment of Evidence"? Or does the law only recognize tangible objects as evidence that can be concealed?

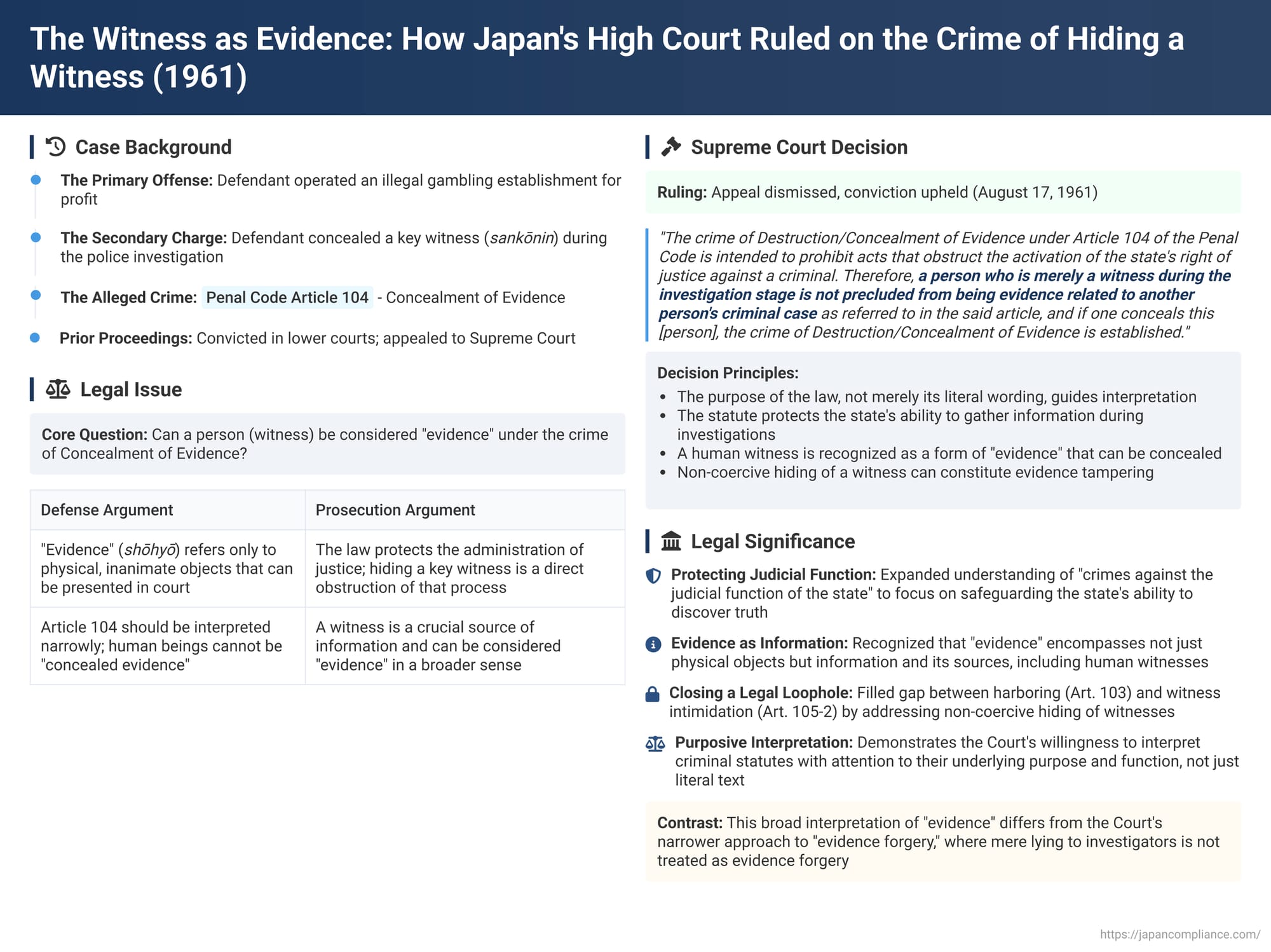

This fundamental question—whether a human being can be the object of evidence tampering—was the subject of a pivotal, albeit brief, ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on August 17, 1961. The decision, arising from a case involving an illegal gambling operation, established a powerful legal principle that significantly broadened the scope of what it means to obstruct justice in Japan.

The Facts: The Gambling Den and the Hidden Witness

While the full, detailed facts of the case are not elaborated upon in the concise text of the final Supreme Court decision, the legal issue it resolved is clear. The case involved a defendant charged with opening a gambling place for profit. In connection with this primary offense, the defendant was also charged with the crime of Concealment of Evidence under Article 104 of the Penal Code. The act that formed the basis of this second charge was the hiding of a key witness—a sankōnin, or person of interest—during the police investigation phase to prevent them from being questioned by the authorities.

The Legal Question: Can a Person Be Considered "Evidence"?

The defense's argument, both in the lower courts and on appeal, would have centered on the very definition of "evidence" (shōhyō) as used in the Penal Code.

- The Defense Position: The defense would have argued that Article 104, which punishes the act of destroying, damaging, or concealing "evidence related to a criminal case of another," applies only to physical, inanimate objects. Hiding a person, they would contend, is not a crime against "evidence."

- The Prosecution's Position: The prosecution's stance, which ultimately prevailed, was that the law's purpose is to protect the administration of justice, and hiding a key witness is a direct and potent method of obstructing that process.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Person Can Be Evidence

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's appeal and upheld the conviction. In its brief but momentous decision, the Court laid down a clear and purposive interpretation of the law. It held:

"The crime of Destruction/Concealment of Evidence under Article 104 of the Penal Code is intended to prohibit acts that obstruct the activation of the state's right of justice against a criminal. Therefore, a person who is merely a witness during the investigation stage is not precluded from being evidence related to another person's criminal case as referred to in the said article, and if one conceals this [person], the crime of Destruction/Concealment of Evidence is established."

This ruling was groundbreaking. It definitively established that a human witness can be the legal object of the crime of evidence tampering.

Analysis: Protecting the Judicial Process Itself

The 1961 decision reflects a substantive, rather than a purely literal, understanding of the concept of "evidence." The Court focused on the function and purpose of the law, which is to protect the integrity of the state's criminal justice system.

- The Protected Interest: Crimes like harboring a criminal, evidence tampering, and perjury are collectively known as "crimes against the judicial function of the state." Their purpose is to safeguard the state's ability to discover the truth, correctly identify perpetrators, and apply the law fairly. This particular offense, Concealment of Evidence, is aimed at preventing the obstruction of the state's exercise of its investigative powers.

- "Evidence" as Information: The Supreme Court's ruling implicitly recognizes that "evidence" is not just about physical objects, but about the information those objects (or people) hold. A witness's potential testimony is a primary source of information crucial to any investigation. By physically hiding the source of that information—the person—the defendant is, in substance, concealing the evidence itself.

- Closing a Legal Loophole: This decision was critical for closing a potential loophole in the law. Other related statutes cover similar but distinct acts:The 1961 ruling addressed a different scenario: the non-coercive hiding of a witness who may not be a suspect themselves. Without this interpretation of Article 104, an offender could potentially sabotage an investigation with impunity by persuading a key witness to go into hiding, an act that might not fit the definition of either harboring or intimidation.

- Harboring a Criminal (Art. 103): This crime applies when the person being hidden is the suspect or perpetrator of a crime.

- Witness Intimidation (Art. 105-2): This crime involves using threats or force to prevent a witness from testifying or to compel them to give false testimony.

- The Contrast with False Testimony: The Court's willingness to interpret "evidence" broadly here stands in interesting contrast to its historical reluctance to treat a witness's false statement as the crime of "evidence forgery." For decades, Japanese courts have held that a witness simply lying to the police does not constitute evidence forgery, in part because other, more specific crimes like perjury exist to handle false testimony under oath. The 1961 decision can be seen as the other side of this coin: where no other specific statute clearly criminalized the act of hiding a witness, the Court applied the general "Concealment of Evidence" statute to prevent a clear obstruction of justice from going unpunished.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1961 decision remains a foundational precedent in the Japanese law of evidence tampering. It established the vital principle that a human witness, as a unique source of information, is a form of "evidence" that the law will protect from concealment. By looking past a narrow, physical definition of the word and focusing on the substantive purpose of the statute—the protection of the state's ability to administer justice—the Court ensured that those who attempt to silence testimony by hiding the testifier are held criminally accountable. The ruling serves as a powerful affirmation that any act designed to make a key source of information unavailable to investigators is a direct attack on the integrity of the justice system itself.