The Winny Decision: Japan's Supreme Court on Aiding and Abetting in the Digital Age

Case: The Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. 2009 (A) 1900

Decision Date: December 19, 2011

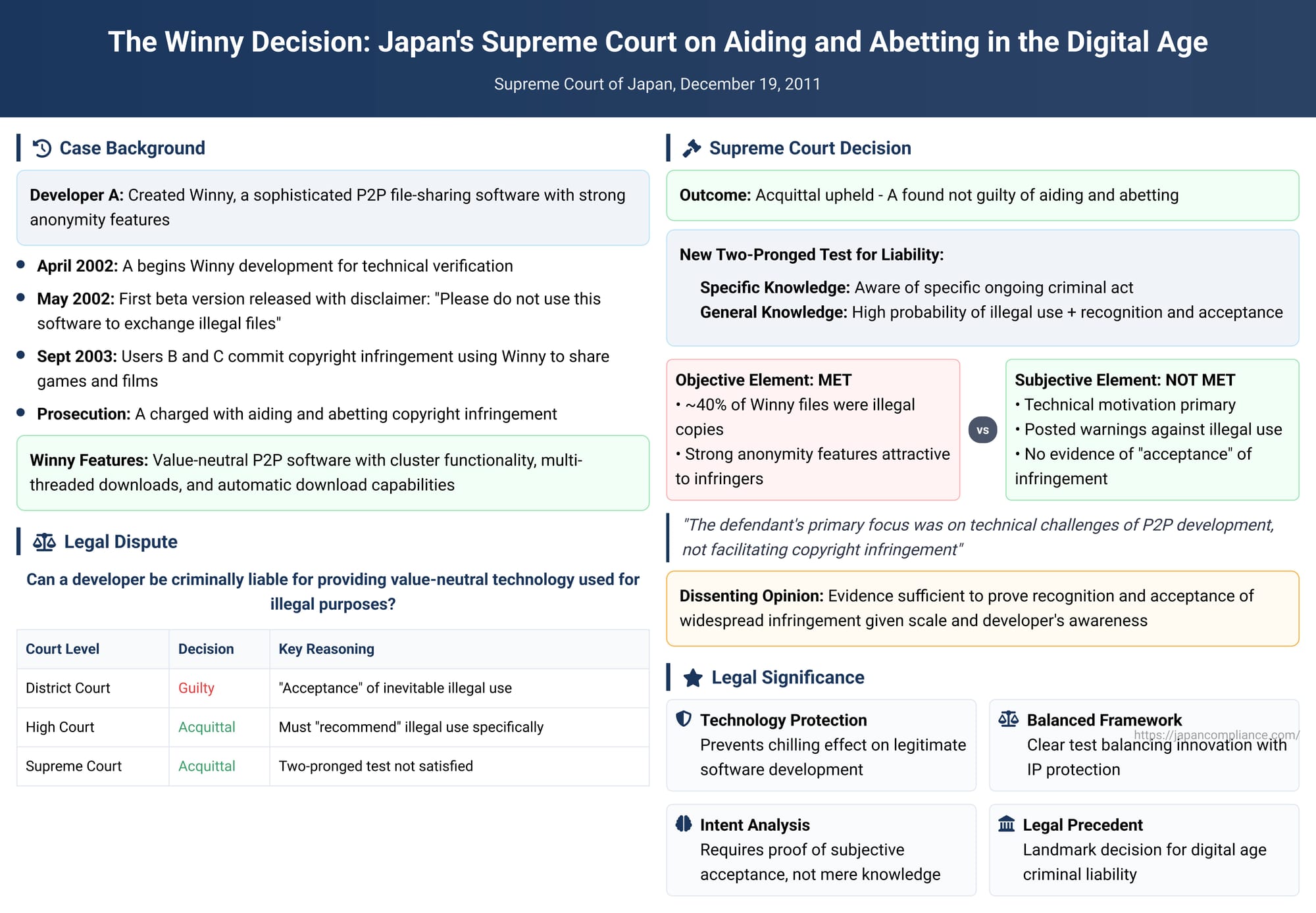

In a landmark decision that has had profound implications for technology development and intellectual property law in Japan, the nation's Supreme Court acquitted the developer of a peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing application, establishing a critical legal standard for what constitutes criminal aiding and abetting through the provision of "value-neutral" technology. The case, involving the software known as "Winny," navigated the complex intersection of technological innovation, copyright protection, and the limits of criminal liability.

Factual Background

The defendant, A, was a developer who created a sophisticated P2P file-sharing software named Winny. The software was designed to operate without a central server, allowing users to connect directly with each other to exchange files. Winny incorporated several advanced features that distinguished it from other contemporary P2P clients. These included functions designed to ensure a high degree of user anonymity and to facilitate the efficient search and transfer of large files, such as cluster functionality, multi-threaded downloads, and automatic download capabilities.

From a technical standpoint, Winny was a "value-neutral" tool. It could be used to share any type of digital file, for purposes both legal (e.g., distributing open-source software, academic research, or personal files) and illegal. The choice of how to use the software was left entirely to the end-user. A developed Winny with the stated technical objective of verifying the performance of a new P2P system that combined anonymity and efficiency. He began development in April 2002 and released the first beta version on his website the following month. The development process was iterative; A would release updated versions and solicit feedback from users. This method of public, iterative development is a common and rational practice in software engineering. On his website, A included a disclaimer, stating, "Please do not use this software to exchange illegal files."

The case arose when two individuals, B and C (the principal offenders), used Winny to commit copyright infringement. Between September 11 and 12, 2003, B used a version of Winny downloaded from A's website to make 25 copyrighted video games available for download to the public. Shortly thereafter, between September 24 and 25, 2003, C used a different version of Winny, also obtained from A's site, to illegally share two copyrighted films.

Prosecutors did not charge A as a principal offender. Instead, they indicted him for aiding and abetting the copyright infringements committed by B and C, arguing that by developing and distributing Winny, he knowingly facilitated their crimes.

The District Court: A Focus on Real-World Usage

The Kyoto District Court, in its ruling, found A guilty. The court acknowledged that the Winny software itself was technologically neutral. However, it argued that determining the illegality of providing such a tool required looking beyond its technical nature to its actual use in society.

The court found that at the time, file-sharing software, including Winny, was widely used for copyright infringement. Winny, in particular, had gained a reputation as a "safe" tool for illegal sharing due to its strong anonymity features and efficiency. The District Court concluded that A was aware of this reality. It reasoned that A, recognizing and "accepting" that Winny would be used for widespread copyright infringement, continued to develop and distribute it. This "acceptance" of the inevitable illegal use was deemed sufficient to establish the requisite criminal intent for aiding and abetting. A was sentenced to a fine of 1.5 million yen.

The High Court: A Stricter Test for Liability

A appealed the decision to the Osaka High Court, which overturned the conviction and acquitted him. The High Court took a much more cautious approach, emphasizing the need to avoid chilling legitimate software development. It established a significantly stricter test for finding a developer liable for aiding and abetting.

The High Court ruled that for the provider of a value-neutral tool to be held criminally liable, it was not enough that the provider merely recognized the possibility or even the likelihood of illegal use. Instead, the prosecution had to prove that the provider distributed the software with the specific intention of having it used for illegal acts as its sole or primary purpose. This would typically involve actively "recommending" the software for such illicit uses.

Applying this test, the High Court found that while A may have recognized the possibility of copyright infringement by some users, there was no evidence that he promoted or intended Winny to be used primarily for illegal purposes. His disclaimers, technical focus, and lack of active encouragement for infringement led the court to conclude that he did not meet this high bar for liability. The acquittal by the High Court was then appealed by the public prosecutor to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Final Word: A New, Nuanced Standard

The Supreme Court of Japan upheld the High Court's acquittal of A, but it did so on different legal grounds. The Court rejected the High Court's narrow test, while simultaneously crafting a more nuanced and comprehensive framework for analyzing liability in such cases.

Rejection of the High Court's "Recommendation" Test

First, the Supreme Court found that the High Court’s requirement that the provider must have "recommended" the software for illegal use was an erroneous interpretation of Japan's Penal Code. Article 62, which defines complicity, contains no such requirement. The Court stated that this test was an unwarranted restriction on the established principles of aiding and abetting and lacked a sufficient legal basis.

The Supreme Court's Two-Pronged Test for Liability

In place of the High Court's standard, the Supreme Court articulated a new test for determining when the provision of a value-neutral tool can constitute criminal aiding and abetting. This test is designed to prevent an over-chilling effect on technological development while still holding providers accountable under specific circumstances. The Court outlined two distinct scenarios where liability could arise:

- Specific Knowledge: The provider is aware of a specific, ongoing criminal act by another person and, recognizing this, provides the tool to facilitate that specific crime. This prong was not applicable to A's case, as he had no knowledge of the specific infringements planned by B and C.

- General Knowledge of High Probability: This second prong applies to cases of mass distribution to the general public. It contains both an objective and a subjective element, both of which must be satisfied:

- Objective Element: The nature of the software, its objective usage patterns, and the method of its provision must be such that there is a high probability that a non-exceptional range of users will use it for illegal acts (in this case, copyright infringement).

- Subjective Element (Mens Rea): The provider must have recognized and accepted this high probability of illegal use by a non-exceptional range of users.

Application of the Test to A's Case

The Supreme Court then meticulously applied this new test to the facts of the Winny case.

Objective Element: Met

The Court concluded that the objective element was satisfied. It considered Winny's powerful anonymity and efficiency features, which made it highly attractive for copyright infringers seeking to avoid detection. Furthermore, it examined evidence of the software's actual use. Citing survey data, including one from an industry association, Company K, the court noted estimates that around 40% of the files circulating on the Winny network were infringing copies of copyrighted works. Based on these factors, the Court held that there was, objectively, a high probability that a non-exceptional portion of Winny's user base would employ it for copyright infringement.

Subjective Element: Not Met

This was the decisive element leading to A's acquittal. The Court found that the prosecution had failed to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that A possessed the requisite subjective intent. Specifically, it was not convinced that A had recognized and accepted the high probability of widespread infringement.

The Court supported this conclusion with several observations:

- A's primary motivation appeared to be technical. His focus was on the technological challenge of creating a next-generation P2P system and, later, a P2P-based bulletin board system (BBS).

- A consistently posted warnings on his website and in development forums, urging users not to engage in illegal activities. While the Court did not see these as a complete defense, they were considered evidence against a subjective acceptance of illegality.

- A's online comments about hoping for "new business models" were interpreted by the Court as being premised on a system where copyright holders' rights would ultimately be protected, not a desire to collapse the existing copyright regime.

- The fact that A himself downloaded some copyrighted files was considered weak evidence that he understood the overall statistical reality of infringement across the entire network.

- The Court found it plausible that A's main interest was in the technical aspects of his creation, and that he may not have fully recognized or accepted the social consequences of its use. His intent was not directed at facilitating infringement, even if that was a foreseeable outcome.

Because the subjective element of the test was not met, the Court concluded that A lacked the criminal intent (specifically, a form of intent known as dolus eventualis, or acceptance of a foreseen consequence) required for an aiding and abetting conviction. The acquittal was therefore upheld.

The Dissenting Opinion

The decision was not unanimous. One justice issued a strong dissent, arguing that A should have been found guilty.

The dissenting justice agreed with the majority's legal framework—the two-pronged test for liability. The point of departure was not the law, but the application of the law to the facts. The dissent argued that the evidence was sufficient to prove that A did, in fact, recognize and accept the high probability of widespread infringement.

The dissent highlighted the following points:

- A was an active participant in online forums where the use of Winny for copyright infringement was openly discussed.

- He was aware of media reports and magazine articles that touted Winny's "safety" for illegal file-sharing.

- The objective scale of infringement—with estimates of 40% to 50% of files being illegal copies—was so massive that it was implausible for the developer not to have recognized this reality.

- The dissent viewed A's warnings as insufficient. Knowing the high probability of harm, A continued to provide and improve the software without implementing any technical measures to inhibit or mitigate the infringement. This continued provision, in the face of such knowledge, was tantamount to "acceptance" of the outcome.

In the dissent's view, A's actions, taken as a whole, satisfied both the objective and subjective prongs of the test, and a conviction for aiding and abetting was warranted.

Conclusion and Significance

The Winny decision is one of the most important legal rulings in Japan concerning technology and criminal law. By acquitting the developer, the Supreme Court sent a clear signal that it wished to avoid creating a legal environment that would unduly stifle technological innovation. The fear of a "chilling effect" on developers was a palpable concern underlying the majority opinion.

However, the Court did not grant a blanket immunity to technology providers. The two-pronged test it established creates a clear, albeit high, bar for criminal liability. It rejects a simplistic approach and instead demands a careful, fact-intensive inquiry into both the objective reality of a tool's use and the provider's subjective state of mind. A provider cannot be held liable simply because their tool can be used for crime. But if a tool becomes overwhelmingly used for illegal purposes, and the provider knows and accepts this reality while continuing to distribute it without mitigation, the door to liability remains open.

The case serves as a crucial legal precedent, balancing the societal interest in protecting intellectual property against the equally important interest in fostering technological progress. It underscores that in the digital age, the line between a neutral tool and a criminal instrument is not always bright, and determining liability requires a nuanced understanding of both technology and intent.