The "Waikiki" Trademark Case: A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Geographical Indications

Judgment Date: April 10, 1979

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 53 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 129 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

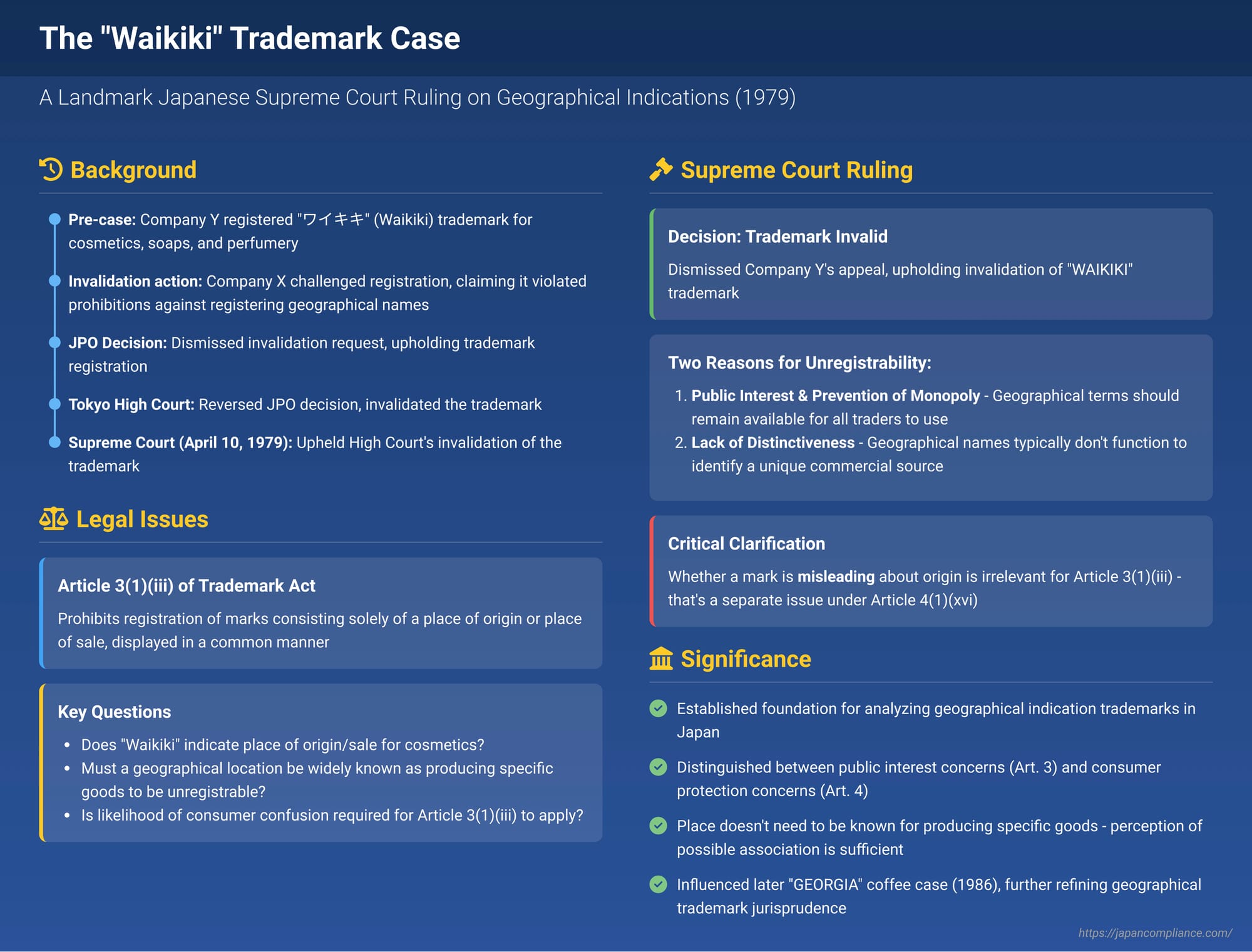

This case, often referred to as the "Waikiki Case," is a seminal decision in Japanese trademark law. It provides crucial clarification on the unregistrability of trademarks that consist solely of geographical indications. The Supreme Court's reasoning has had a lasting impact on how Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Japanese Trademark Law is interpreted and applied.

Background of the Dispute

The appellant, Company Y, was the owner of a registered trademark consisting of the Katakana characters for "ワイキキ" (Waikiki), written horizontally. The designated goods for this trademark fell under the former Class 4, specifically: "soaps (excluding those belonging to medicines), dentifrices, cosmetics (excluding those belonging to medicines), and perfumery."

The appellee, Company X, initiated proceedings by filing a request with the Japan Patent Office (JPO) for an invalidation trial against Company Y's "WAIKIKI" trademark. Company X argued for invalidation on two main grounds:

- Violation of Trademark Law Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 (pre-1991 amendment): Company X contended that the "WAIKIKI" trademark consisted solely of a mark indicating the origin or place of sale of the goods, displayed in a common way. This provision generally prevents the registration of such descriptive marks.

- Violation of Trademark Law Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 16: Company X also argued that the trademark was likely to cause misidentification regarding the quality of the goods. The underlying concern was that consumers would mistakenly believe the products originated from Waikiki, associating them with the perceived qualities of products from that well-known tourist destination.

The JPO, in its initial trial decision, sided with Company Y. It found that the "WAIKIKI" trademark did not fall under either of the cited provisions and dismissed Company X's request for invalidation.

Dissatisfied with the JPO's decision, Company X appealed to the Tokyo High Court, seeking the rescission of the JPO's trial decision.

The Tokyo High Court's Ruling

The Tokyo High Court overturned the JPO's decision, finding in favor of Company X. The High Court concluded that the "WAIKIKI" trademark was indeed invalid under both Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 and Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 16 of the Trademark Law.

The High Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Fame of "Waikiki": At the time of the trademark's registration (April 1970), "Waikiki" was already widely recognized in Japan as a prominent tourist destination, encompassing Waikiki Beach and its adjacent bustling commercial areas.

- Association with Souvenirs: The court noted that floral perfume was a representative souvenir product from Waikiki.

- Likelihood of Misleading Consumers (Origin): Consequently, the High Court determined that if the "WAIKIKI" trademark were used on its designated goods, particularly items like perfumes and other cosmetics, it would likely lead ordinary consumers to mistakenly believe that these products were souvenirs produced or sold in Waikiki. This misapprehension would extend to other designated goods as well; consumers would likely assume these items were also produced or sold in the tourist locale of Waikiki.

- Application of Article 3(1)(iii): Based on this likelihood of misidentification regarding origin and place of sale, the High Court found that the trademark consisted solely of a mark indicating the "place of origin, place of sale...of the goods, displayed in a common manner."

- Application of Article 4(1)(xvi): The court also found that the trademark was "likely to cause misidentification of the quality of the goods," tying this back to the misleading impression about the product's origin.

- Rejection of Counterarguments: Company Y had argued that Waikiki was not specifically recognized in Japan as a place of origin or sale for perfumes, and that floral perfumes were sold in various other locations in Hawaii, not just Waikiki. The High Court dismissed these arguments. It clarified that for a geographical term to fall under Article 3(1)(iii), it is not necessary for the location to be widely known as the definitive or sole place of origin or sale for the specific goods. The court emphasized that allowing a single entity to monopolize a term like "Waikiki" for such goods would be inappropriate. The purpose of Article 3(1)(iii), the court suggested, is to prevent such monopolization of terms that others in the trade might need to use descriptively.

Following this defeat at the Tokyo High Court, Company Y, the trademark holder, appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the Tokyo High Court's decision to invalidate the "WAIKIKI" trademark. While the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's findings on both Article 3(1)(iii) and Article 4(1)(xvi), its judgment provided a particularly significant and detailed explanation of the rationale behind Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3.

The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning regarding Article 3(1)(iii) can be summarized as follows:

Why Marks Indicating Origin/Place of Sale are Unregistrable:

The Supreme Court elucidated that trademarks listed under Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 (i.e., those consisting solely of marks indicating the place of origin, place of sale, etc., of goods, displayed in a common manner) are deemed to lack the requirements for trademark registration for two primary reasons:

- Public Interest and Prevention of Monopoly: These types of marks are essentially descriptive indicators of a product's geographical origin, place of sale, or other characteristics. As such, they are considered necessary and appropriate indications for anyone involved in trade to use. Granting an exclusive right (a monopoly) to a single specific person or entity to use such a mark would be contrary to the public interest. The marketplace benefits when all traders can freely use descriptive geographical terms.

- Lack of Distinctiveness (Trademark Function): Marks that merely describe geographical attributes are generally considered to be commonly used. Consequently, in most cases, they lack the inherent capacity to distinguish the goods of one business from those of another. This inherent "distinctiveness" or "source-identifying function" is the very essence of what a trademark is supposed to do. If a mark cannot perform this function, it cannot serve as a trademark.

Clarification on the "Misleading" Aspect:

A crucial part of the Supreme Court's decision was its explicit separation of the criteria for Article 3(1)(iii) from the issue of whether a mark is "misleading."

The Court acknowledged that when such geographically descriptive marks are used on products, they may often lead to misapprehensions about the product's origin, place of sale, or other characteristics. However, the Court stated emphatically that this issue of potential misidentification is a matter to be considered under Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 16 of the Trademark Law (which deals with marks likely to cause misidentification of the quality of goods, often linked to origin).

Critically, the Supreme Court ruled that the likelihood of causing such misidentification is not a prerequisite for a mark to be deemed unregistrable under Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3.

The appellant, Company Y, had argued for a narrower interpretation of Article 3(1)(iii). They contended that the provision should only apply to marks that:

a) Indicate a place widely known as the origin or place of sale for the goods in question, AND

b) Are likely to cause misidentification as to the origin or place of sale if used on those goods.

The Supreme Court unequivocally rejected this interpretation. It found no basis for restricting the scope of Article 3(1)(iii) in such a manner. The provision's primary concerns, as outlined by the Court, are the public interest in keeping descriptive terms available for all and the inherent lack of distinctiveness of such terms, irrespective of whether they are also misleading in a particular context.

Affirmation of the High Court's Factual Findings:

The Supreme Court found that the Tokyo High Court's determination was correct. The High Court had concluded that the "WAIKIKI" trademark, in relation to its designated goods (soaps, cosmetics, perfumes, etc.), did indeed consist solely of a mark indicating the place of origin or sale of the goods, displayed in a common manner (thus violating Article 3(1)(iii)). Furthermore, the High Court correctly found that using this trademark on the designated goods was likely to cause consumers to misidentify the origin or place of sale of those goods (thus also violating Article 4(1)(xvi)). The Supreme Court stated that these findings by the High Court were justifiable based on the evidence and reasoning presented in the High Court's judgment, and there were no legal errors in the process.

The Supreme Court also dismissed Company Y's specific argument that using the "WAIKIKI" trademark on designated goods other than perfume would not cause misidentification. The Court pointed out that the High Court had already legitimately determined that misidentification was likely even for those other goods.

Therefore, the Supreme Court, with a unanimous opinion from the presiding justices, dismissed the appeal, and Company Y was ordered to bear the costs of the appeal.

Significance and Broader Interpretation of Article 3(1)(iii)

The Waikiki case is a cornerstone in understanding Article 3(1)(iii) of the Japanese Trademark Law. Its principles continue to guide the JPO and the courts.

Core Tenets of Article 3(1)(iii):

As clarified by the Supreme Court in this case, the refusal to register trademarks consisting solely of geographical indications (used in a common way) rests on two main pillars:

- Inappropriateness for Monopolization (Public Interest): Geographical names are considered essential descriptive tools that should be available for all businesses to use truthfully. Allowing one entity to monopolize such a term would unfairly restrict competition and access to necessary descriptive language.

- Lack of Distinctiveness: Generally, a geographical name by itself does not function to identify a unique commercial source of goods or services. Consumers are likely to see it as an indication of origin or location, not as a brand name.

The "GEORGIA" Coffee Case - Reinforcement and Elaboration:

Several years after the Waikiki decision, the Supreme Court issued another important ruling concerning geographical trademarks in the "GEORGIA" case (January 23, 1986). This case involved the trademark "GEORGIA" for coffee. The "GEORGIA" case further refined the interpretation of Article 3(1)(iii), stating that for the provision to apply, it is not necessary for the designated goods to actually be produced or sold in the geographical location indicated by the trademark.

Instead, it is sufficient if consumers or traders would generally perceive that the designated goods are likely to be produced or sold in that location. This means that if the public associates a place with certain types of goods, even if that association isn't based on actual, widespread production there, the geographical name used for those goods can fall foul of Article 3(1)(iii). This aligns with the Waikiki ruling’s stance that the place doesn't need to be widely known as the actual production site. The perception or association is key.

Combined Impact of Waikiki and Georgia:

Taken together, the Waikiki and Georgia Supreme Court decisions establish a clear framework:

- The primary reasons for not registering purely geographical marks are the public interest in free use of descriptive terms and the inherent lack of distinctiveness.

- Whether the mark is misleading as to origin is a separate question for Article 4(1)(xvi), not a requirement for Article 3(1)(iii).

- The geographical location does not need to be famous as an actual production/sales area for the specific goods; a general perception or association by consumers or traders is enough.

"Ordinary Manner of Use":

Article 3(1)(iii) specifies that the geographical indication must be "displayed in a common manner" (or "ordinarily used manner"). This implies that if a geographical name is presented in a highly stylized, unique, or fanciful way, or if it is combined with other distinctive elements (such as a unique logo, a coined word, or arbitrary graphics), the trademark as a whole might escape the prohibition of Article 3(1)(iii). The focus of this provision is on marks that consist solely of the geographical term presented plainly.

Acquired Distinctiveness (Secondary Meaning) - Article 3(2):

Japanese Trademark Law, under Article 3, Paragraph 2, provides an exception for marks that initially fall under provisions like Article 3(1)(iii). If, through extensive use, a trademark that was originally non-distinctive (e.g., a geographical name) has become recognized by consumers as indicating the goods or services of a particular business source, it is said to have acquired "distinctiveness" or "secondary meaning." In such cases, the trademark can be registered despite its descriptive nature.

However, demonstrating acquired distinctiveness for a purely geographical name can be challenging, especially in light of the public interest considerations. There's a general reluctance to grant monopolies on geographical terms even if some level of consumer recognition as a brand is shown, because these terms may become relevant for others to use descriptively in the future (e.g., if a region not previously known for a product begins producing it).

Invalidation of Improperly Registered Marks:

If a trademark is registered in contravention of Article 3(1)(iii) (e.g., a purely geographical name that has not acquired distinctiveness), it is vulnerable to an invalidation action under Article 46, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Trademark Law.

An important practical consideration is the statute of limitations. Under Article 47, Paragraph 1, an invalidation trial based on a violation of Article 3 (including Article 3(1)(iii)) cannot be requested after five years have passed from the date of trademark registration. This five-year "period of repose" means that even if a mark was arguably registered improperly under Article 3(1)(iii), it becomes immune to this specific ground of invalidation after five years. (This limitation does not apply to all grounds for invalidation; for example, marks registered in bad faith or those conflicting with prior well-known marks may have different rules).

Scope of "Geographical Name" in Practice:

The Japan Patent Office's Trademark Examination Guidelines provide insight into what constitutes a "geographical name" for the purposes of Article 3(1)(iii). The term is interpreted broadly and includes:

- Domestic and foreign geographical names: This covers countries (current and former), capitals, regions, administrative divisions (like prefectures, cities, towns, villages, special wards in Japan), states, state capitals, counties, provinces, provincial capitals, old provincial names, old regional names, well-known commercial streets, tourist destinations (including their immediate vicinity), lakes, mountains, rivers, parks, and even maps depicting such geographical features.

- Consumer/Trader Perception: If traders or consumers would generally recognize that the designated goods are produced or sold, or designated services are provided, in the territory indicated by the geographical name, then that name is considered to refer to a "place of origin," "place of sale," or "place of provision of services."

- Country Names and Famous Locations: Names of countries (including common abbreviations and historical names of currently existing countries) and other famous domestic or international geographical names are generally presumed to fall under Article 3(1)(iii) as indicators of origin, sales location, or service provision location.

Geographical Names and Future Developments:

The rationale for restricting the monopolization of geographical names also considers potential future developments. A place not currently associated with a particular product might become so in the future due to various factors, such as climate change impacting agricultural production (e.g., new wine-growing regions emerging). If a geographical name were already monopolized as a trademark, it could hinder the ability of new producers in that region to describe their products accurately. This prospective consideration reinforces the cautious approach to allowing registration of geographical names, even under the acquired distinctiveness provisions.

Conclusion

The Waikiki Supreme Court decision is a foundational ruling in Japanese trademark law that clearly defines the reasons for the unregistrability of trademarks consisting solely of geographical indications used in a common way. By emphasizing the dual rationales of public interest (preventing monopolies on descriptive terms essential for trade) and lack of inherent distinctiveness, and by separating these from the issue of whether a mark is misleading (which falls under a different statutory provision), the Court provided much-needed clarity.

This judgment, especially when read alongside the subsequent "GEORGIA" case, underscores a protective stance towards keeping geographical terms open for common use, reflecting a balance between protecting trademark holders' rights and ensuring a fair and competitive marketplace where descriptive terms remain accessible to all. The principles from the Waikiki case continue to be a critical reference for businesses and legal practitioners navigating the complexities of trademarking geographical names in Japan.