The Usurped Wasteland: A Japanese Ruling on Stealing Land You Already Occupy

How do you "steal" something that cannot be moved, like a parcel of land? While the common law tradition often handles such matters through civil torts like trespass, Japanese criminal law contains a specific felony: "usurpation of real property" (fudōsan shindatsu-zai). This crime, analogous to theft, raises fascinating legal questions about the nature of possession over immovable property. Can an owner who has fled and abandoned a property still be said to possess it? And can a person who has a legal right to be on a property be guilty of "stealing" it from the owner?

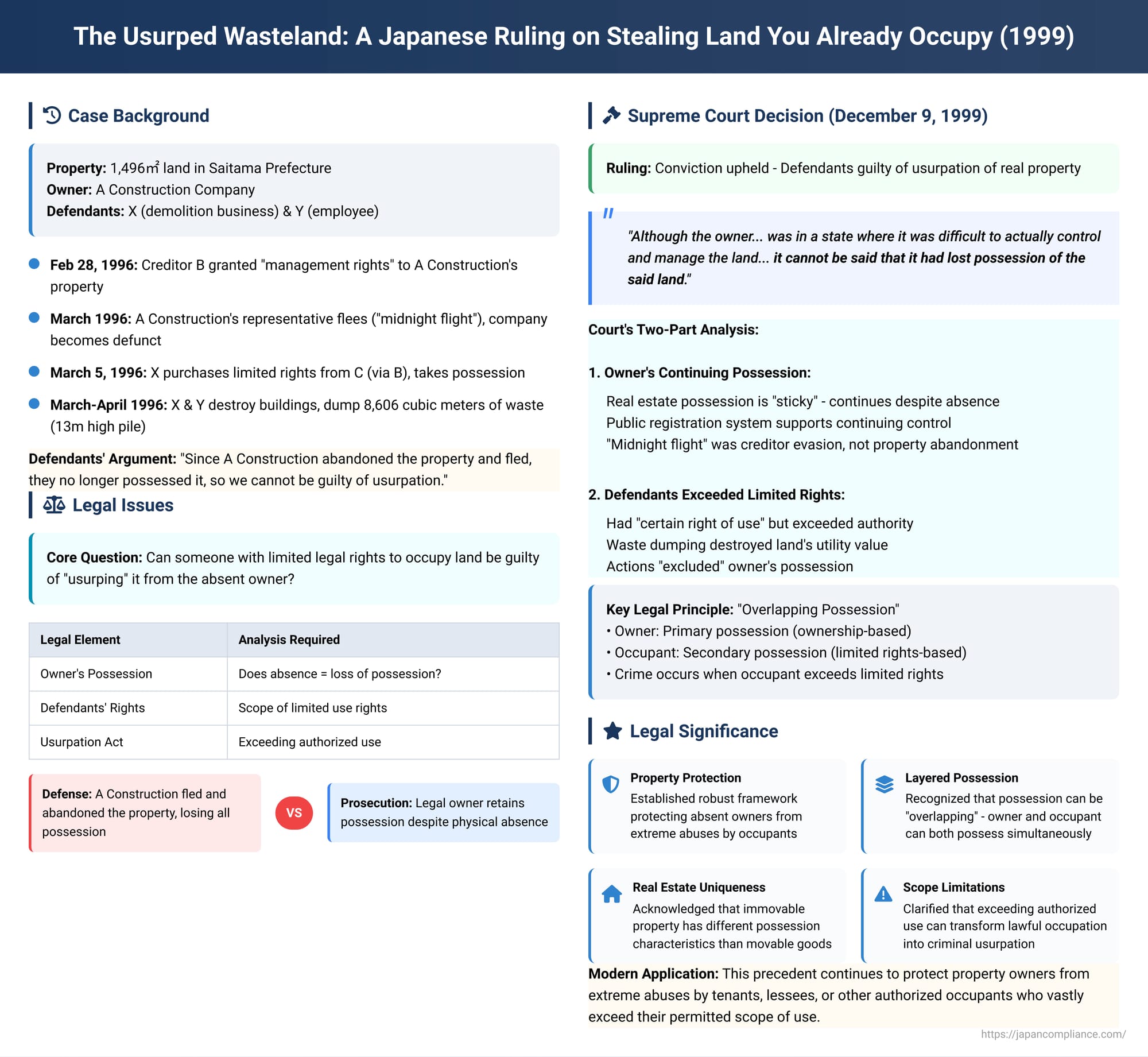

These complex questions were at the center of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on December 9, 1999. The case, involving a defunct construction company, a series of questionable property right transfers, and the transformation of a commercial lot into a massive industrial waste dump, provided crucial clarity on how the law protects possession of real estate.

The Facts: From Construction Yard to Industrial Wasteland

The property at the heart of the case was a 1,496-square-meter parcel of land in Saitama Prefecture, owned by a company called A Construction. The company, which had several workshops and warehouses on the site, fell into financial distress after bouncing a check. On February 28, 1996, one of its creditors, a company named B, demanded and was granted the right to "manage" the property. However, the right B acquired was very limited, amounting to no more than a leasehold on the existing buildings and the associated right to use the land.

Shortly thereafter, B transferred its limited rights to another company, C. At the same time, the representative of the owner, A Construction, absconded with his family in a so-called "midnight flight" (yonige) to evade creditors, and the company became effectively defunct.

Enter the defendants. Defendant X, who ran a demolition business, purchased the limited rights from C on March 5, 1996, and took possession of the property. His plan was to use the conveniently located land as a dumping ground for industrial waste. Over the next few weeks, X and his employee, defendant Y, proceeded to destroy the existing buildings on the property. They then dumped an enormous volume of waste—approximately 8,606 cubic meters of mixed construction debris and waste plastics—onto the land, creating a pile over 13 meters high. This act rendered the land unusable and made it incredibly difficult and expensive to restore to its original state.

The defendants were charged with and convicted of usurpation of real property. They appealed, arguing that since the original owner had fled and abandoned the property, they no longer possessed it, and therefore it could not be "usurped."

The Legal Framework: "Usurpation" as the Theft of Real Estate

The crime of usurpation of real property (Article 235-2 of the Penal Code) was established in a 1960 revision to the code. The legislative intent was to create a crime for real estate that was analogous to the crime of theft for movable property. As such, it requires the infringement of another person's "possession" (sen'yū) of the property. "Possession," in this criminal law context, means "factual control." However, the nature of factual control over immovable land is inherently different from the control one has over a wallet or a car. This case forced the Supreme Court to clarify what "possession" means in the context of real estate.

First Legal Issue: Possession by an Absent Owner

The first question for the Court was whether A Construction, the original owner, still possessed the land after its representative had disappeared and the company was no longer operating. Could an absent, non-managing owner still have "possession" in the eyes of the law?

The Supreme Court's answer was a clear and resounding yes. The Court stated:

"Although the owner of the land in question, A Construction, was in a state where it was difficult to actually control and manage the land in question because its representative had disappeared and the company was effectively defunct, it cannot be said that it had lost possession of the said land."

This finding is based on the unique characteristics of real estate. Unlike movable property, land cannot be hidden or physically carried away. Its ownership is a matter of public record through a registration system. Therefore, as long as the legal owner has not formally abandoned the property or had their rights legally extinguished, their possession is deemed to continue, even without active, on-site management. The owner's "midnight flight" was interpreted as an act to evade creditors, not an intent to abandon the property itself.

Second Legal Issue: Usurpation by a Lawful Occupant

The second, more complex issue was how the defendants could be guilty of usurping land that they had a limited legal right to occupy. The Supreme Court resolved this by carefully examining the scope of their rights versus the nature of their actions.

The Court acknowledged that the defendants "had a certain right of use concerning the land in question." However, it found that they "exceeded the authority of that right of use, piling a massive amount of waste on the land and causing the loss of the land's utility value by making it difficult to restore it to its original state."

By acting so radically beyond the scope of their limited rights, the defendants were found to have "excluded the possession of A Construction and transferred it to their own control." This, the Court concluded, constituted the crime of usurpation.

Analysis: The Concept of "Overlapping Possession"

The Supreme Court's decision strongly supports a legal concept that can be described as "overlapping" or "layered" possession. This view holds that in situations involving leases or limited use rights, possession is not an all-or-nothing concept.

- The owner (A Construction) retained a primary, overarching possession of the property, rooted in its ownership.

- The occupant (the defendants) held a secondary, limited possession, defined by the scope of their legitimate right of use.

Under this framework, the defendants' actions were legally justified only as long as they remained within the bounds of their limited right. When they radically exceeded that right by destroying the property's value and treating it as their personal waste dump, their actions became an illegal infringement on the owner's primary and co-existing possession. This infringement is what constitutes the criminal act of usurpation.

This can be contrasted with a more typical landlord-tenant relationship. A tenant with a long-term lease has very broad rights of use. Minor violations of the lease agreement would almost certainly be treated as a civil matter, not a criminal usurpation, because they do not fundamentally exclude the owner's ultimate rights in the same way that turning a property into a toxic wasteland does.

Conclusion: A Framework for Protecting Real Property

The 1999 Supreme Court ruling provides crucial clarity on the crime of usurpation of real property, a concept with few direct parallels in common law systems. It establishes two vital principles for understanding possession in the context of real estate:

- Possession of real estate is "sticky." An owner's possession is presumed to continue even in their physical absence, as long as they have not legally abandoned the property. The public registration of land ownership provides a powerful basis for this continuing state of control.

- Possession can be layered. A person with a limited right to use a property can still be found guilty of usurping it from the owner if their actions so radically exceed the scope of their granted rights that they effectively extinguish the owner's co-existing possession and the property's value.

The ruling establishes a robust framework that protects property owners from extreme abuses, even from individuals who may have some legitimate, but limited, reason to be on their land. It confirms that in Japanese criminal law, "possession" is a nuanced concept that adapts to the unique nature of the property it protects.