The Use of Force by Railway Security Officers: A 1973 Japanese Supreme Court Landmark

Case Title: Trespass, Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Judgment Date: April 25, 1973

Case Number: 1968 (A) No. 837

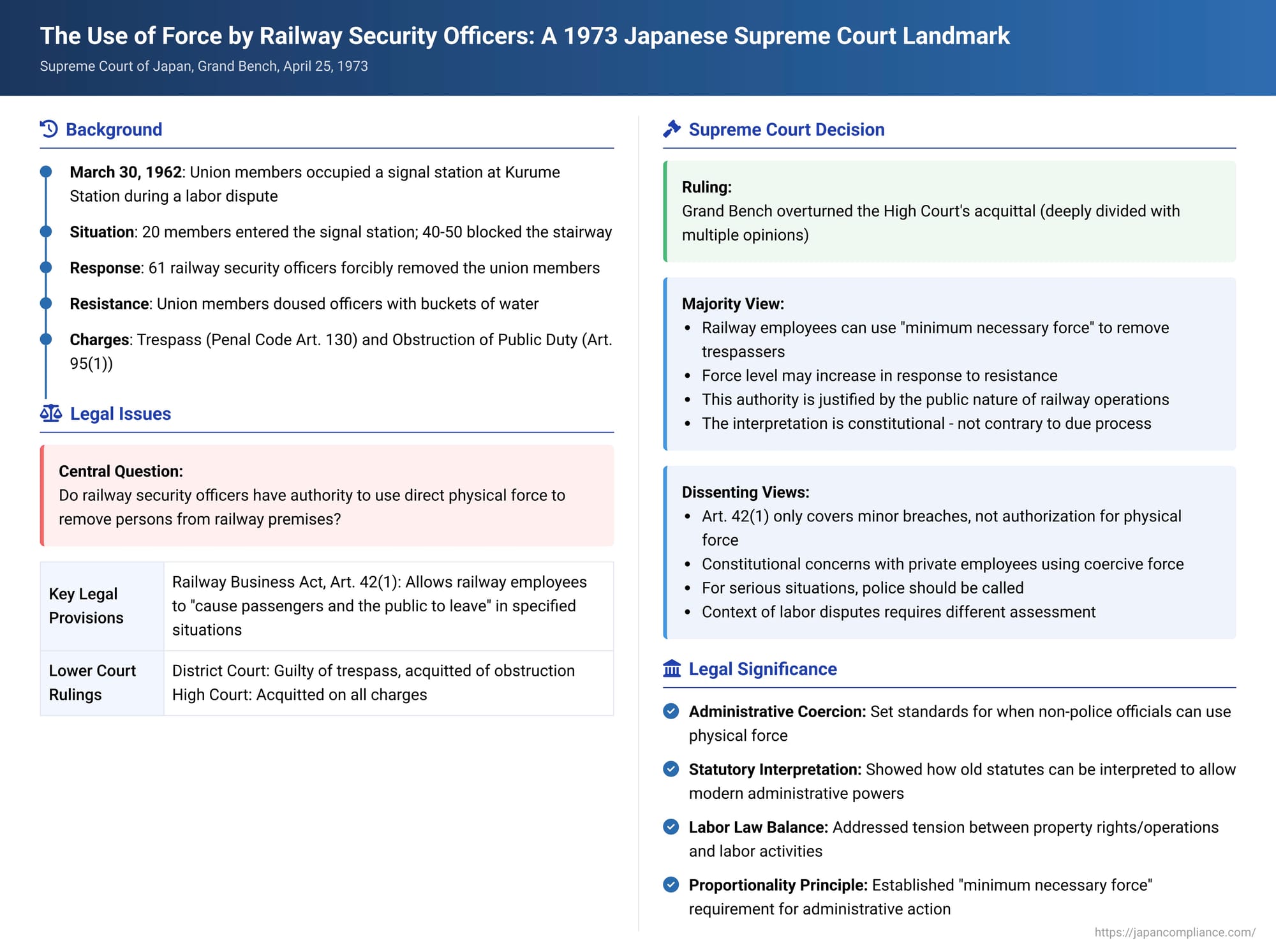

This pivotal 1973 Grand Bench judgment of the Supreme Court of Japan delves into the legality of physical force used by railway security personnel during a labor dispute, and the subsequent criminal charges against union members who resisted. The case, involving defendants S. Y. and others, who were members of the Japanese National Railways (JNR) labor union, raised fundamental questions about the scope of authority granted by the Railway Business Act and the limits of permissible action during industrial action.

Factual Background: A Labor Dispute Escalates

The events unfolded on March 30, 1962, at Kurume Station, amidst a labor dispute where JNR union members were pressing demands related to year-end allowances. The union's actions took the form of picketing, aiming to ensure the effectiveness of a planned strike.

Specifically:

- Approximately 20 union members entered the second-floor signal station of the east lever frame at Kurume Station. This entry was in defiance of a prohibition issued by the station master, M. K.

- Another 40 to 50 union members occupied the staircase leading to the signal station, sitting so densely that passage was blocked.

- The objective of this picketing was to persuade the three employees working in the signal station to participate in a two-hour workplace rally scheduled during work hours on the following day, March 31.

The JNR authorities repeatedly demanded that the union members vacate the premises. When these demands were ignored, 61 railway security officers (tetsudō kōan shokuin) were mobilized to forcibly remove the union members.

In response to this forcible removal, the defendants, who were among the union members, doused the railway security officers with dozens of buckets of water thrown from the signal station. This act of resistance was repeated in the early hours of March 31, when the removal efforts by the security officers resumed after an interruption.

As a result of these actions, the defendants were prosecuted for trespass under Article 130 of the Penal Code and for obstruction of the performance of public duty under Article 95, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code.

The lower court proceedings yielded differing outcomes:

- First Instance (Kurume Branch, Fukuoka District Court, December 14, 1966): The court found the defendants guilty of trespass but acquitted them of the charge of obstruction of performance of public duty. Both the defendants and the public prosecutor appealed this decision.

- Appeal Court (Fukuoka High Court, March 26, 1968): The High Court acquitted the defendants on all charges. The public prosecutor then appealed this acquittal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Decision

The Supreme Court, sitting as a Grand Bench, overturned the Fukuoka High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings. The justices were significantly divided, leading to a majority opinion, a substantial supplementary opinion supporting the majority, and three separate dissenting opinions.

The Majority Opinion

On Trespass:

The majority found that the union members, including the defendants, had disregarded the station master's explicit prohibition when they entered and occupied the signal station. The signal station was identified as a facility of extreme importance for the normal and safe operation of trains. By entering and occupying it, the union members effectively excluded the station master's control over this critical area.

The Court stated that when assessing the illegality of acts that constitute criminal offenses but are performed during a labor dispute, all circumstances, including the fact that the act was part of a dispute, must be considered. The central question is whether the act is permissible from the perspective of the entire legal order. In this instance, the defendants' actions—entering such a vital facility with the intent to persuade essential personnel to abandon their duties, despite warnings and prohibitions—were deemed not to lack illegality under the Penal Code. The Court also held that finding them criminally responsible for this trespass did not violate Article 28 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right of workers to organize and to act collectively.

On Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty:

The core of the majority's reasoning on this charge rested on its interpretation of Article 42, Paragraph 1 of the Railway Business Act. This provision allows railway employees (tetsudō kakariin) to remove passengers or members of the public from trains or railway premises in certain specified situations, such as unauthorized entry.

The majority opined that:

- Use of Force Authorized: While railway employees should first urge voluntary departure, if individuals do not comply, or in unavoidable circumstances such as imminent danger, the employees are empowered to use the minimum necessary force appropriate to the specific situation. This can be done without necessarily waiting for police intervention.

- Constitutionality: This interpretation of Article 42(1), grounded in the public nature and importance of railway operations, constitutes a reasonable regulation and does not contravene Article 31 of the Constitution (due process). Railway security officers, as JNR employees, were tasked with maintaining safety and order under internal JNR regulations, and their actions in this capacity could be considered official duties.

- Application to the Case: The JNR union members' occupation of the signal station, a critical operational facility, constituted an unauthorized intrusion under Articles 37 and 42(1)(iii) of the Railway Business Act. The JNR authorities, responsible for safe train operations, were justified in seeking to regain control of the facility by removing the union members.

The railway security officers, acting as railway employees, could lawfully remove the occupying union members and, in doing so, could use the minimum necessary force. The determination of what constitutes "minimum necessary force" depends on the specific circumstances, including the level of resistance from the union members.

The Court found that, based on the facts (repeated requests to leave ignored, the nature of the defendants' resistance including dousing with numerous buckets of water on a cold night, some of which allegedly contained coal cinders and urine, and injuries sustained by both sides), there was scope to conclude that the force used by the railway security officers was within the bounds of what was minimally necessary.

If the officers' actions were indeed within this limit, they were performing their duties lawfully. Consequently, the defendants' acts of throwing water to impede these actions would constitute the crime of obstruction of performance of public duty.

The High Court's acquittal was based on the view that the union members' actions were part of a legitimate labor dispute and that the force used by the railway security officers exceeded permissible limits. The Supreme Court found this interpretation of Article 42(1) and its application of constitutional principles to be erroneous.

Dissenting and Supplementary Opinions

The deep divisions within the Grand Bench were evident in the multiple opinions issued:

1. Supplementary Opinion of Six Justices (Supporting the Majority):

These justices aimed to reinforce the majority view, particularly in light of one of the dissenting opinions. They argued that:

- The authority of railway employees under Railway Business Act Article 42(1) is analogous in purpose to powers granted to aircraft captains (Aviation Act Art. 73-3(1)) or air carriers (Aviation Act Art. 86-2(1)) to maintain safety and order within their respective transport environments. All these powers stem from the public nature of the transport services and the need to ensure their safe and reliable operation.

- The dissenting view that Article 42(1) only covers minor infractions misunderstands the scope of the article, which can include acts posing direct danger to passengers or railway safety, such as trespassing in critical areas like the signal station in this case.

- The argument that Article 42(1), being a Meiji-era law, is incompatible with the current Constitution's emphasis on personal liberty fails to recognize that the provision has been retained through numerous revisions and addresses a timeless need for railway operational safety. The act of removing someone from railway property to maintain order is a limited measure and not an absolute prohibition on personal freedom that the Constitution would forbid, especially when balancing against public safety and the interests of other passengers.

- The dissenting view, by strictly limiting the use of force by railway personnel and requiring police intervention for most physical removals, sets an overly stringent and impractical standard for railway operations. It would also mean that for minor violations, the only recourse might be arrest for a criminal offense, which could be a disproportionately severe response.

- Attempting to legislatively define every specific instance where railway personnel might need to use force is likely impossible or would result in overly generalized and thus unhelpful provisions.

- The dissent, by heavily emphasizing the "personal liberty" of those violating railway rules, neglects the broader public interest, railway safety, and the essential task of constitutional interpretation which involves balancing conflicting interests.

2. Dissenting Opinion of Four Justices:

This group fundamentally disagreed with the majority's interpretation of Railway Business Act Article 42(1):

- Limited Scope of Article 42(1): The acts targeted by Article 42(1) are generally minor breaches of order or infringements of a similar, relatively trivial nature. Even when these acts are punishable under the Railway Business Act, they only attract minor fines or non-penal fines. To authorize powerful measures like direct physical force against individuals for such minor offenses is difficult to justify rationally.

- Constitutional Concerns: Granting coercive powers involving direct physical force against persons, even to state officials, raises serious constitutional questions under the current Constitution, which highly values personal dignity and freedom. To grant such powers to private individuals (which would include employees of private railway companies, as the Act applies to them too) is exceptionally problematic from a constitutional standpoint. The majority's interpretation allowing railway personnel to use such strong force to suppress union activities was something the original drafters of Article 42 likely never envisioned.

- Need for Specific Legislation: If there are situations in railway transport where the use of force by railway personnel is deemed necessary, it should be authorized through specific and narrowly defined legislative measures that detail the permissible scope of such actions. Relying on an expansive interpretation of the existing, general terms of Article 42 is inappropriate.

- Permissible Actions under Article 42(1): The power to remove under Article 42(1), while potentially including the use of minimal tangible force in truly unavoidable circumstances, does not extend to direct physical coercion against a person's body. In cases requiring such force, police assistance should be sought. If there is no time to call the police, and there is urgent danger to life or limb, or a grave and immediate threat to railway transport safety or facilities, then physical force might be justified only to the extent legally permissible under principles of self-defense or emergency necessity.

- Critique of Aviation Act Analogy: The situation on a railway is different from that on an aircraft in flight, which is an isolated environment where immediate external help is unavailable. Railways operate on land with easier access to police.

3. Dissenting Opinion of Justice I. M.:

This justice argued that while railway security officers have investigative powers for crimes on railway premises, their actions in this case were based on their capacity as JNR employees under the Railway Business Act, not their criminal investigation authority. Article 42(1) should be interpreted to allow physical force only as an exceptional measure, in the most minimal degree, in unavoidable circumstances, and must not amount to coercion. The force used by the officers in this case, described as dragging resisting union members down stairs, exceeded this limit and was therefore not a lawful performance of duty.

4. Dissenting Opinion of Justice I. K.:

This justice focused on the trespass charge against one defendant (Y) and the obstruction charge.

- On Trespass (Defendant Y): Defendant Y entered the signal station peacefully to persuade employees to join a union rally. This was an organizing activity. Given the nature of company-based unions in Japan, using company facilities for union activities is often unavoidable. Such entry, if not causing substantial disruption, might not even meet the threshold for criminal trespass, or could be considered a legitimate union activity protected under labor law.

- On Obstruction: The occupation of the stairs by picketers was to protect the planned workplace rally from anticipated interference by management or right-wing groups; it was defensive. The railway security officers' forceful removal of these picketers, including dragging them, was excessive for the alleged offense (trespass by "the public," a questionable application to JNR employees engaged in union activity). If any removal was warranted after a request to leave was ignored, the force used should have been akin to everyday, minor physical contact (e.g., taking an arm, pushing a shoulder) that is generally socially tolerated. The majority's approval of a more significant level of force by railway employees, contingent on the degree of "resistance" (which included merely holding on to railings), was an overreach.

Analysis and Lasting Significance

This 1973 Grand Bench decision came at a time of significant ideological tension surrounding the labor rights of public sector employees in Japan. The JNR itself was a massive state-owned enterprise, and its labor relations were often contentious. The railway security officer system, where JNR employees were vested with certain policing powers, was also a unique feature of that era; this system was abolished with the privatization of JNR in 1987, and its functions were absorbed by regular prefectural police forces.

The core legal debate revolved around the interpretation of Article 42(1) of the Railway Business Act, a law dating back to 1900 (Meiji 33). The provision allowed railway staff to "cause passengers and the public to leave the train or railway grounds" under certain conditions, including trespass (defined in Article 37). Critically, the Act did not specify the methods or limits of such removal, particularly regarding the use of physical force. This ambiguity allowed for the starkly contrasting interpretations seen in the majority and dissenting opinions.

The principle against self-help is fundamental in modern legal systems; coercive actions by state or quasi-state actors generally require a clear legal basis. "Immediate coercion" (sokuji kyōsei) – the use of direct force by administrative bodies without prior judicial or administrative orders – is particularly scrutinized because of its invasive nature. Under Japan's Constitution, which prioritizes the respect for fundamental human rights, any infringement on personal liberty requires explicit and clear legal authorization (Article 31, due process). Japan's pre-war Administrative Execution Act had allowed for broad powers of immediate coercion, but its abuses led to its repeal after World War II. The current Police Duties Execution Act permits police officers to use immediate coercion, but only under strict conditions and limitations.

The majority opinion in this case effectively found that Article 42(1) of the Railway Business Act provided a sufficient legal basis for railway employees (including security officers acting in that capacity) to use "minimum necessary force." This was justified by the "public nature" of the railway business and the need to ensure its safe and reliable operation. The proportionality principle – that force must be the minimum necessary – was acknowledged by all sides, but its application differed. The majority felt that the circumstances, including the union members' resistance, could justify the level of force used.

The dissenting opinions, however, raised serious concerns. They argued that Article 42(1) was intended for minor breaches of order and could not be stretched to authorize direct physical coercion against individuals, especially by employees of what could also be private railway companies (as the Act applied to both). They highlighted the constitutional sensitivity of allowing non-police personnel to use physical force, particularly when police assistance could potentially be summoned. Some dissenters felt that if such powers were truly necessary, they should be granted through new, specific legislation with clear safeguards and limitations, rather than by broadly interpreting an old, vaguely worded statute. The comparison with the powers of aircraft captains was also contested, given the different operational environments (an isolated aircraft versus a land-based railway system).

The case also touched upon the delicate balance between property rights/managerial authority and the rights of workers to engage in union activities, including picketing, on company premises. While the majority found the occupation of a critical facility like a signal station to be an illegal trespass even in the context of a labor dispute, some dissenting views suggested that peaceful union activities within company premises might not always constitute trespass if they don't cause undue disruption.

This judgment, decided by a narrow margin in a deeply divided Grand Bench, remains a significant case in Japanese administrative law concerning the use of force by non-police officials and the interpretation of statutory authority for coercive measures. It underscores the ongoing tension between the state's interest in maintaining public order and safety in vital public services, and the protection of individual liberties and collective labor rights. While the specific context of JNR and its railway security officers has passed into history, the underlying legal principles regarding the necessity of clear legal authorization for administrative coercion and the application of the proportionality principle continue to be relevant.