The Uphill Battle: Consumer Damages and Price Cartels in Japan – Insights from the Oil Cartel Supreme Court Rulings

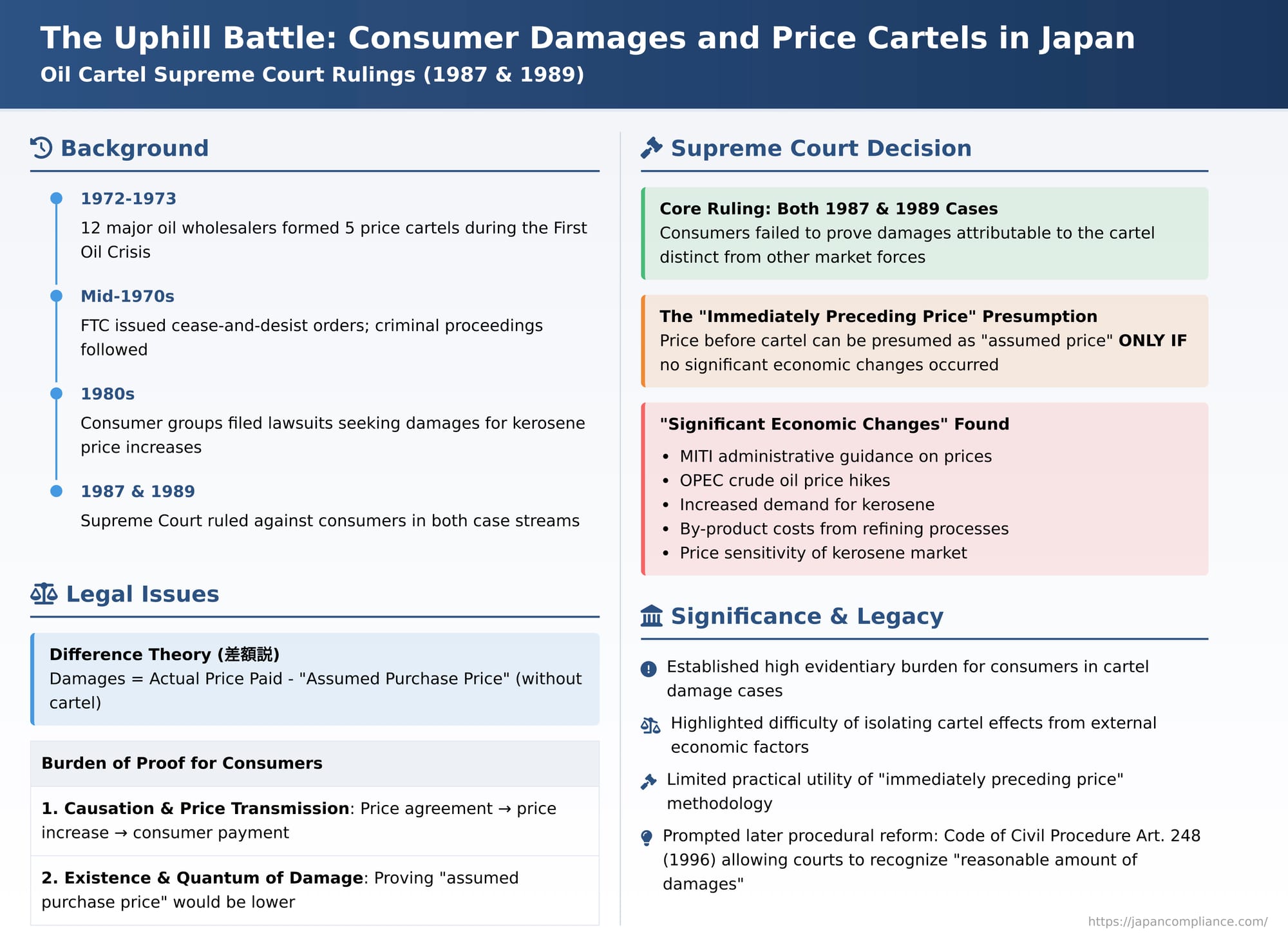

In the annals of Japanese antitrust law, a pair of Supreme Court decisions, one from July 2, 1987, and another from December 8, 1989, stand as landmark rulings concerning consumers' ability to claim damages resulting from illegal price cartels. These cases, arising from price-fixing agreements by twelve major Japanese oil wholesalers during the tumultuous "First Oil Crisis" of the early 1970s, highlight the significant hurdles consumers face in proving harm and quantifying damages, even when an unlawful cartel seems apparent.

The Backdrop: Crisis and Collusion

Between approximately November 1972 and November 1973, a group of twelve oil wholesalers in Japan engaged in five coordinated price agreements (cartels) for petroleum products, including gasoline, heavy oil, kerosene, and jet fuel. This period coincided with the First Oil Crisis, triggered by sharp increases in crude oil prices by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), leading to widespread economic disruption and social confusion in Japan. The price cartels, seen as exacerbating an already dire situation, had a profound societal impact. They resulted not only in administrative actions by Japan's Fair Trade Commission (FTC), including cease-and-desist orders, but also escalated to criminal proceedings.

Against this backdrop, groups of consumers from various regions who had purchased kerosene during this period filed lawsuits seeking compensation for the damages they claimed to have suffered due to these price cartels. The legal journey was complex, with differing outcomes in the lower courts. In one stream of cases (referred to as Case ① in some analyses, culminating in the December 1989 Supreme Court judgment), consumers had initially won at the High Court level. In another stream (Case ②, leading to the July 1987 Supreme Court judgment), consumers had lost at the High Court. Ultimately, the Supreme Court overturned the consumer victory in Case ① and dismissed the consumers' appeal in Case ②, effectively ruling against the consumers in both instances at the highest judicial level.

Proving Harm: The "Difference Theory" and Burden of Proof

The central legal question revolved around how to calculate the damages, if any, incurred by consumers. Both the lower courts and the Supreme Court adopted the "difference theory" (差額説 - sagaku-setsu) to define damages in price cartel cases. This theory posits that the damage is the extra expenditure a purchaser was forced to make due to the illegal price agreement. Essentially, it's the difference between the price actually paid by the consumer and the hypothetical price that would have been formed in the market had the cartel not existed (the "assumed purchase price" or 想定購入価格 - sōtei kōnyū kakaku).

The Supreme Court delineated a stringent two-part requirement for what consumers, as plaintiffs, must assert and prove to claim damages from the oil wholesalers:

- (a) Causation and Price Transmission: Consumers must demonstrate a causal link showing that the wholesalers' price agreement led to an increase in their selling prices (refinery gate prices), which was then passed on through the distribution chain (wholesale prices), ultimately resulting in a tangible increase in the retail prices actually paid by the final consumers.

- (b) Existence and Quantum of Damage: Consumers must prove that, had the price cartel not been implemented, a retail price lower than the one they actually paid would have been established in the market. This involves demonstrating not only that they suffered a loss but also quantifying that loss.

The more contentious aspect of this burden of proof lay in establishing the "assumed purchase price"—a price that, by its very nature, never actually existed in the marketplace.

The Elusive "Assumed Purchase Price"

Recognizing the inherent difficulty in proving a hypothetical price, the courts considered how this "assumed purchase price" might be inferred.

The "Immediately Preceding Price" Presumption:

Generally, the retail price of the product immediately before the implementation of the price cartel (the "immediately preceding price" or 直前価格 - chokuzen kakaku) could be presumed to represent the "assumed purchase price". This presumption, however, came with a significant caveat.

The Caveat: "Significant Economic Changes":

This presumption would only hold if there were no significant changes in economic conditions, market structure, or other economic factors that would affect the formation of retail prices during the period from the cartel's implementation to the time the consumers purchased the product.

If such significant economic changes did occur, the "immediately preceding price" alone could not be used to infer the "assumed purchase price". Instead, a more comprehensive analysis would be required, taking into account the specific price formation characteristics of the product, the nature and extent of the economic changes, and other relevant price-forming factors to estimate the hypothetical price.

Shifting the Burden, Then Reaffirming It:

Crucially, the Supreme Court placed the responsibility of proving the absence of such significant economic changes squarely on the plaintiff consumers if they wished to rely on the "immediately preceding price" presumption. If consumers could not prove this negative (i.e., that no significant economic changes took place), the presumption would not apply.

This was a key point of divergence from one of the High Court rulings (in Case ①), which had initially found for the consumers. That High Court had suggested that, out of fairness, unless the defendant oil companies could prove "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō)—such as specific, predictable price increases that would have occurred even without the cartel—the "immediately preceding price" should be deemed the "assumed purchase price". This approach had effectively shifted the evidentiary burden on this point to the defendants. The Supreme Court rejected this burden-shifting, reiterating that the onus remained on the consumers.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Overwhelmed by Economic Factors

In applying these principles to the oil cartel cases, the Supreme Court found that the period in question was indeed marked by "significant economic changes". The Court acknowledged several critical factors that had influenced the petroleum market, many of which were identified by the lower courts as well:

- Administrative Guidance by MITI: The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI, now METI) was implementing administrative guidance aimed at suppressing the rapid rise in petroleum product prices.

- OPEC Price Hikes: The global price of crude oil was increasing dramatically due to the actions of OPEC.

- Increased Demand for Kerosene and By-Product Costs: There was a surge in demand for kerosene. Efforts to increase kerosene production consequently led to the overproduction of other less-in-demand petroleum products (by-products of the refining process). Managing the inventory of these surplus by-products incurred additional costs for the wholesalers.

- Price Sensitivity of Kerosene: Kerosene was relatively inexpensive compared to other petroleum products. This characteristic made it more susceptible to price increases when underlying cost factors rose, as wholesalers might find it easier to pass on costs in this segment.

- Higher Specific Costs for Kerosene: Compared to other petroleum products, kerosene required additional costs related to its refining and storage.

Given these substantial and "remarkable" economic fluctuations, the Supreme Court concluded that the necessary precondition for relying on the "immediately preceding price" as the "assumed purchase price" was absent. The economic landscape had shifted too dramatically.

Furthermore, the Court considered the impact of MITI's price-control measures. It inferred that even if the oil wholesalers had not engaged in their price-fixing agreements, the wholesale price of kerosene would likely have risen to a level comparable to the price effectively frozen or capped by MITI's guidance, due to the other prevailing upward cost pressures. Consequently, the Court determined that it could not definitively conclude that the "assumed purchase price" at the retail level would have been lower than the prices consumers actually paid. The consumers had failed to establish that they had suffered quantifiable damage attributable to the cartel, separate from these other powerful market forces.

The judgment in Case ② explicitly noted that the High Court's finding—that it was unclear whether the assumed purchase price would have been below the actual retail price—could not be deemed erroneous under the circumstances. Case ① echoed this conclusion regarding the impact of economic changes.

The Antimonopoly Act Article 25 and Evidentiary Challenges

It's relevant to note that Case ② was filed under Article 25 of Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA). This article establishes a form of no-fault liability for damages caused by acts violating the AMA (such as unreasonable restraints of trade, which cartels are), provided that an FTC decision ordering exclusionary measures against the violation has become final and unappealable.

Even under this special provision, the fundamental challenge of proving the quantum of damages (i.e., the "assumed purchase price") remained. The Supreme Court, in its reasoning, confirmed that the principles for calculating damages and the burden of proof concerning the "assumed purchase price" were similar whether the claim was based on general tort law (Civil Code Article 709) or AMA Article 25.

The commentary on these cases highlights the immense practical difficulty for consumers to successfully litigate such claims. Establishing a counterfactual market price in a complex, dynamic economic environment like the oil market during a global crisis is an extraordinarily demanding evidentiary task. The courts acknowledged that determining such a price with theoretical precision is "factually almost impossible".

Judicial Reflections and Subsequent Developments

The difficulty faced by consumers in these cases did not go unnoticed. A supplementary opinion by one of the Supreme Court justices in Case ① acknowledged the extreme difficulty for consumers to meet the burden of proof regarding the "assumed purchase price" and causation under the existing tort law framework. This opinion suggested that one way to make consumer redress more effective would be to amend AMA Article 25 to include a provision for estimating the amount of damages in cartel cases. This could, for example, allow damages to be presumed based on the agreed-upon price increase in the cartel agreement, thereby facilitating easier litigation for consumers under that specific statutory provision.

While AMA Article 25 itself was not amended in this specific way for some time, a later development in Japanese civil procedure is worth noting. An amendment to the Code of Civil Procedure in 1996 introduced Article 248. This provision allows a court to recognize a "reasonable amount of damages" if it is established that damage has occurred, but the nature of the damage makes it extremely difficult to prove the precise amount. This article has since been utilized in other types of antitrust cases, such as those involving bid-rigging. This indicates a broader recognition within the legal system of the challenges in quantifying damages in certain complex scenarios, though it was not the legal basis for the oil cartel decisions of 1987 and 1989.

Key Takeaways

The Supreme Court's decisions in the oil cartel cases underscore several critical points for understanding private enforcement of antitrust law in Japan, particularly from a consumer perspective:

- High Evidentiary Bar for Damages: Consumers face a substantial burden in proving not only the existence of a cartel and its effect on general price levels but also the specific quantum of damages they personally suffered. This involves constructing a reliable model of a hypothetical market free of the cartel's influence.

- Impact of External Economic Factors: In markets subject to significant external shocks or regulatory interventions (like the oil market during the 1970s crisis with OPEC actions and MITI guidance), isolating the precise impact of a cartel on prices becomes exceptionally challenging. Courts will meticulously examine these factors.

- "Immediately Preceding Price" is Not a Panacea: While the price before a cartel's implementation can be a starting point for damage calculation, its utility is limited. Plaintiffs must affirmatively demonstrate that no other significant economic changes occurred that would have independently affected prices.

- Limited Procedural Shortcuts: Even statutory provisions designed to aid plaintiffs, like AMA Article 25's no-fault liability, did not, at the time of these rulings, alleviate the core difficulty of proving the actual amount of loss.

These rulings illustrate a cautious judicial approach, emphasizing rigorous proof of loss and causation before awarding damages. While the legal landscape continues to evolve, the oil cartel cases remain a salient reminder of the complexities inherent in seeking compensation for harm caused by anticompetitive practices in dynamic market conditions.