The Unregistered Landlord: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Asserting Lessor Status

Date of Judgment: March 19, 1974

Case Name: Claim for Ownership Transfer Registration Procedure, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

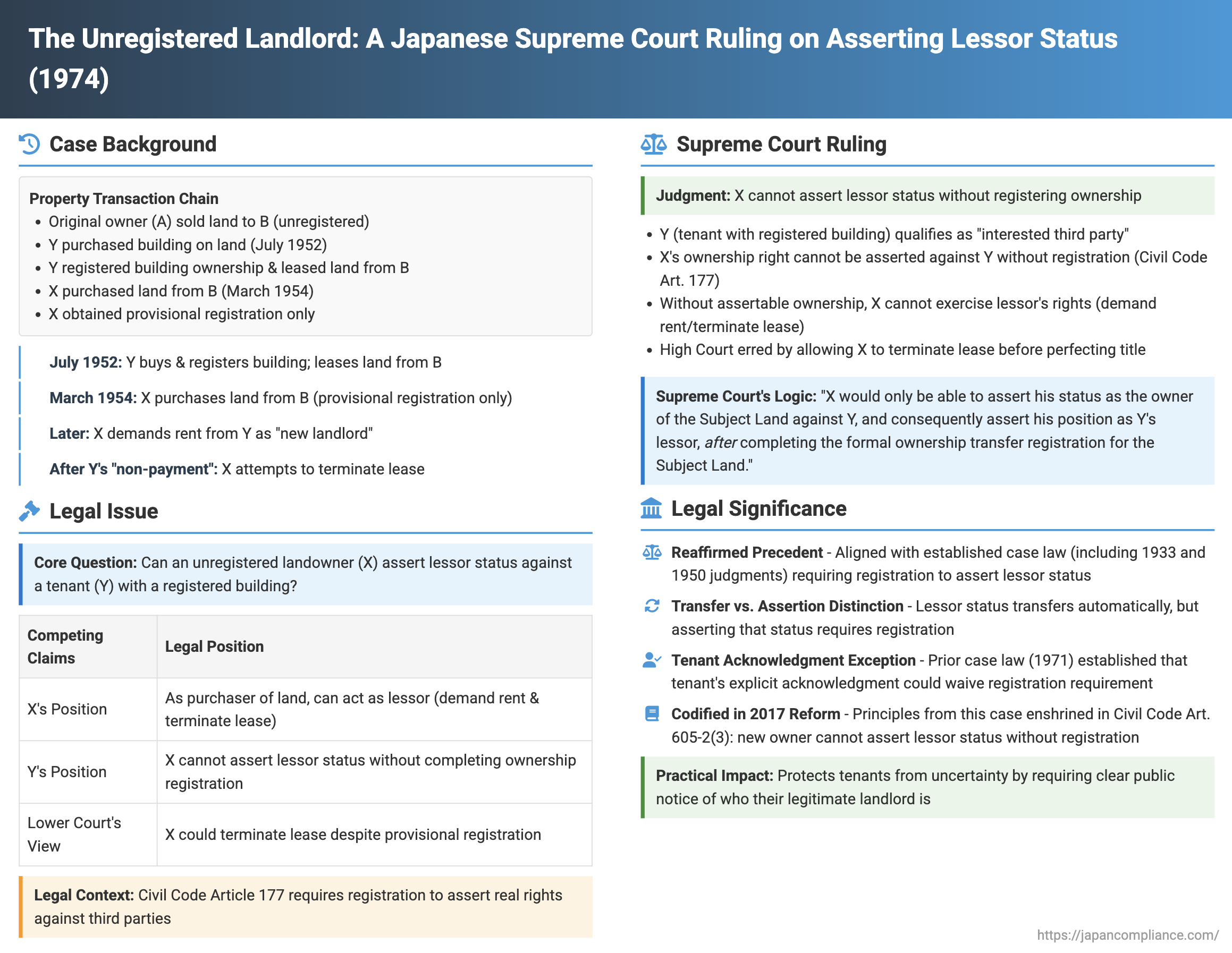

The Japanese legal system places immense importance on property registration as a cornerstone of secure transactions. A pivotal Supreme Court decision on March 19, 1974, shed light on a critical aspect of this system: the ability of a new property owner, who has not yet registered their ownership, to exercise the rights of a lessor against an existing tenant on that property. This case untangles the complexities that arise when the chain of title registration is incomplete, particularly when the tenant has established rights.

The Complex Web of Transactions: A Multi-Layered Dispute

The factual background of this case involves a series of intertwined property dealings and legal claims:

- Initial Land Transaction (Unregistered): The story begins with an individual, A, who was the original owner of a parcel of land (referred to as the "Subject Land"). A sold this land to B, but B never completed the ownership transfer registration, leaving A as the registered owner.

- Tenant's Entry and Building Registration: In July 1952, Y (the defendant in the Supreme Court case) purchased a commercial building situated on the Subject Land. Y duly registered his ownership of this building. Simultaneously, Y entered into a lease agreement with B for the Subject Land beneath the building, recognizing B as the landlord and paying rent to B.

- Sub-Lease and Corporate Connections: Y, the owner of the Subject Building, then leased this building to Company C. Notably, Y served as the managing director of Company C, while X (the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case) was its president.

- Second Land Transaction (Provisionally Registered): In March 1954, X purchased the Subject Land from B. An agreement was made among X, A (the original, still-registered owner), and B (the unregistered owner and Y’s lessor) that the ownership registration would be transferred directly from A to X. This type of direct registration, skipping an intermediate party, is known as an "intermediate omission registration" (chūkan shōryaku tōki). Following the payment in September 1954, only a provisional registration (kari tōki) was made in X's name, securing X's claim for ownership transfer based on a purchase reservation, due to various prevailing circumstances.

- Tenant's Protective Measures: In the interim, Y, the tenant of the Subject Land and owner of the Subject Building, obtained a provisional disposition order from the court against A, prohibiting A from disposing of the Subject Land. This order was also registered.

- Litigation Commences: When X later sought to complete the main registration (hon tōki) of his ownership of the Subject Land, A refused to cooperate. This prompted X to file lawsuits: one against A to compel the main registration, and another against Y seeking Y's consent to X's ownership transfer registration and, critically, the removal of Y's Subject Building from the Subject Land.

- Y's Defenses and X's Counter-Move: X was successful in the initial court proceedings. In the ensuing appeal (which joined the cases against A and Y), Y raised several defenses. Y primarily claimed that he, not X, was the true purchaser of the Subject Land from B in 1954, and that X's provisional registration was a collusive fabrication designed to shield the land from Y's creditors. Alternatively, and crucially for this Supreme Court case, Y argued that even if X were the owner of the Subject Land, Y's lease agreement with B (the previous owner) was valid and could be asserted against X.

In response to Y's alternative defense asserting tenancy, X took action as a purported new lessor: X issued a formal demand to Y for payment of overdue rent within a specified period. When Y allegedly failed to pay within this period, X notified Y that the lease agreement for the Subject Land was terminated. - The High Court's Ruling: The Osaka High Court found that X was indeed the legitimate purchaser of the Subject Land. It also held that Y could assert his leasehold rights against X. However, the High Court concluded that X had validly terminated this lease agreement due to Y's non-payment of rent. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Dilemma

The central question before the Supreme Court was:

Could X, the new owner of the Subject Land who had only a provisional registration and had not yet completed the main ownership transfer registration, legally assert the status and rights of a lessor against Y (the tenant)? Specifically, could X demand rent from Y and terminate Y's lease for non-payment, given that Y had a registered building on the land, thereby perfecting his leasehold rights against third parties?

The Supreme Court's Decision

On March 19, 1974, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered its judgment. It partially quashed the High Court's decision (specifically the part ordering building removal based on lease termination) and remanded that portion back to the Osaka High Court for further proceedings. The remainder of Y's appeal was dismissed.

The Supreme Court's core reasoning was as follows:

- Tenant as an Interested Third Party: The Court recognized Y, who was a lessee of the Subject Land and the owner of a registered building upon it, as a third party having a legitimate interest in any transfer of ownership of the Subject Land.

- Necessity of Ownership Registration (Civil Code Article 177): Under Article 177 of the Japanese Civil Code, which governs the perfection of real rights in immovable property, X could not assert his acquired ownership of the Subject Land against a third party like Y without first completing the registration of this ownership transfer.

- Inability to Assert Lessor's Status Pre-Registration: As a direct consequence of not being able to assert ownership against Y, the Supreme Court concluded that X also could not assert the status of lessor against Y. This meant X could not legitimately exercise lessor's rights, such as demanding rent directly in his capacity as the new owner or terminating the lease agreement for non-payment.

- Acknowledgment of Factual Circumstances: The Court noted Y's explicit challenge to X's ownership claim and X's own admission that the ownership transfer registration for the Subject Land had not yet been completed.

- The Correct Sequence: Registration First: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that X would only be able to assert his status as the owner of the Subject Land against Y, and consequently assert his position as Y's lessor, after completing the formal ownership transfer registration for the Subject Land.

- Error in the Lower Court's Judgment: The High Court had erred in its interpretation of the law by affirming X's right to terminate the lease agreement (based on Y's alleged non-payment of rent to X) before X had perfected his ownership of the Subject Land through registration. X's attempt to terminate was premature.

Unpacking the Decision: Significance and Commentary

This 1974 Supreme Court judgment is significant for reaffirming and clarifying key principles regarding the interplay between property transfer, registration, and leasehold rights.

Reaffirmation of Existing Case Law

The decision aligned with established precedents (such as a Daishin'in judgment from May 9, 1933, and a Supreme Court judgment from November 30, 1950, cited in the 1974 judgment's reasoning). These prior cases had already established that where a tenant has a perfected leasehold right (e.g., through possession of a registered building on leased land, as per the Building Protection Act, or by registration of the lease itself), a new acquirer of the land must register their own ownership to assert their position as the new lessor against that tenant.

Transfer of Lessor's Status vs. Assertion of that Status

The legal commentary surrounding this case often distinguishes between two aspects:

- The Effectuation of Transfer of Lessor's Status: When property subject to a perfected lease is transferred, Japanese case law and legal theory have generally held that the lessor's contractual position (rights and obligations) automatically transfers from the seller to the buyer. This transfer occurs by operation of law, simply due to the property conveyance, without needing a separate agreement with the tenant or even the tenant's consent or notification (as supported by cases like Daishin'in, May 30, 1921, and Supreme Court, August 28, 1964). This was often explained through the concept of a "status-bound obligation relationship" (jōtai saimu kankei), implying the lease obligations are intrinsically tied to land ownership, though this specific concept has faced academic criticism, with alternative theories proposed (e.g., based on the implied will of the parties or as a direct legal consequence of leasehold perfection).

- The Requirement to Assert the Transferred Status: The 1974 Supreme Court judgment directly addresses this second aspect. While the lessor's status might automatically transfer to the new owner (X), for X to assert that status and exercise the associated rights (like collecting rent or terminating the lease) against a tenant (Y) whose leasehold is already perfected against third parties, X must first register his own ownership of the land. This registration requirement isn't strictly about X "perfecting" his ownership against Y's lease in the confrontational sense of Civil Code Article 177 (as Y's lease is already perfected). Instead, legal scholars have described it as a "requirement for the protection of legal standing/qualification" (kenri shikaku hogo yōken) for X to act as lessor, or an interpretation of what constitutes "delivery" of the property in the context of an ongoing lease.

Tenant's Acknowledgment as a Potential Exception

An important nuance in this area of law is the effect of a tenant's acknowledgment. Prior case law (e.g., Supreme Court, December 3, 1971) had indicated that if the tenant explicitly acknowledges or consents to the new owner's status as lessor, the new owner might be able to exercise lessor's rights even without having completed their own title registration. The tenant, by acknowledging the new landlord, essentially waives the right to demand that the new landlord first show a perfected title.

A point of discussion regarding the 1974 judgment was whether Y's "alternative defense" (claiming his lease with B was assertable against X) constituted such an acknowledgment of X's lessor status. If it did, X might have been able to terminate the lease despite his own lack of full registration. However, legal commentary generally refutes this interpretation. An admission or statement made within the context of a hypothetical proposition in an alternative defense (e.g., "Even if X is the owner, my lease is valid...") is not usually treated as a binding, unconditional acknowledgment of X's legal status before that status (X's ownership) is definitively established. Therefore, Y was not deemed to have validly acknowledged X as the lessor at the time X attempted to terminate the lease. This interpretation keeps the 1974 judgment consistent with the 1971 precedent concerning tenant acknowledgment.

Codification in the 2017 Civil Code Revision

The principles reinforced by this 1974 judgment and related case law have been largely incorporated into the Japanese Civil Code through amendments effective in 2017:

- Article 605-2, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code now explicitly states that if real property subject to a lease that has been perfected against third parties is transferred, the lessor's contractual status transfers to the new owner.

- Article 605-2, Paragraph 3 codifies the rule from the 1974 judgment: the new owner cannot assert this transferred lessor status against the tenant unless the new owner has registered their ownership of the property.

The 2017 revisions did not explicitly detail the effect of a tenant's acknowledgment of an unregistered new lessor. However, the prevailing understanding is that the prior case law allowing a tenant to effectively waive the new lessor's lack of registration (by acknowledging them as the landlord) likely continues to apply.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 19, 1974, decision serves as a crucial reminder of the paramount importance of registration in Japanese property law. For a new owner of a leased property to confidently exercise their rights as a lessor against an existing tenant (especially one with perfected leasehold rights), the new owner must, as a general rule, first perfect their own title by completing the ownership registration. Failing to do so can prevent the new owner from taking actions such as collecting rent in their own name or terminating the lease, even if the underlying grounds for such actions otherwise exist. This principle protects tenants from uncertainty regarding the identity of their legitimate landlord and upholds the integrity of the public registration system.