The Unraveling of a Legal Presumption: A 2014 Japanese Supreme Court Case on Paternity, DNA, and the Child's Stability

Date of Judgment: July 17, 2014

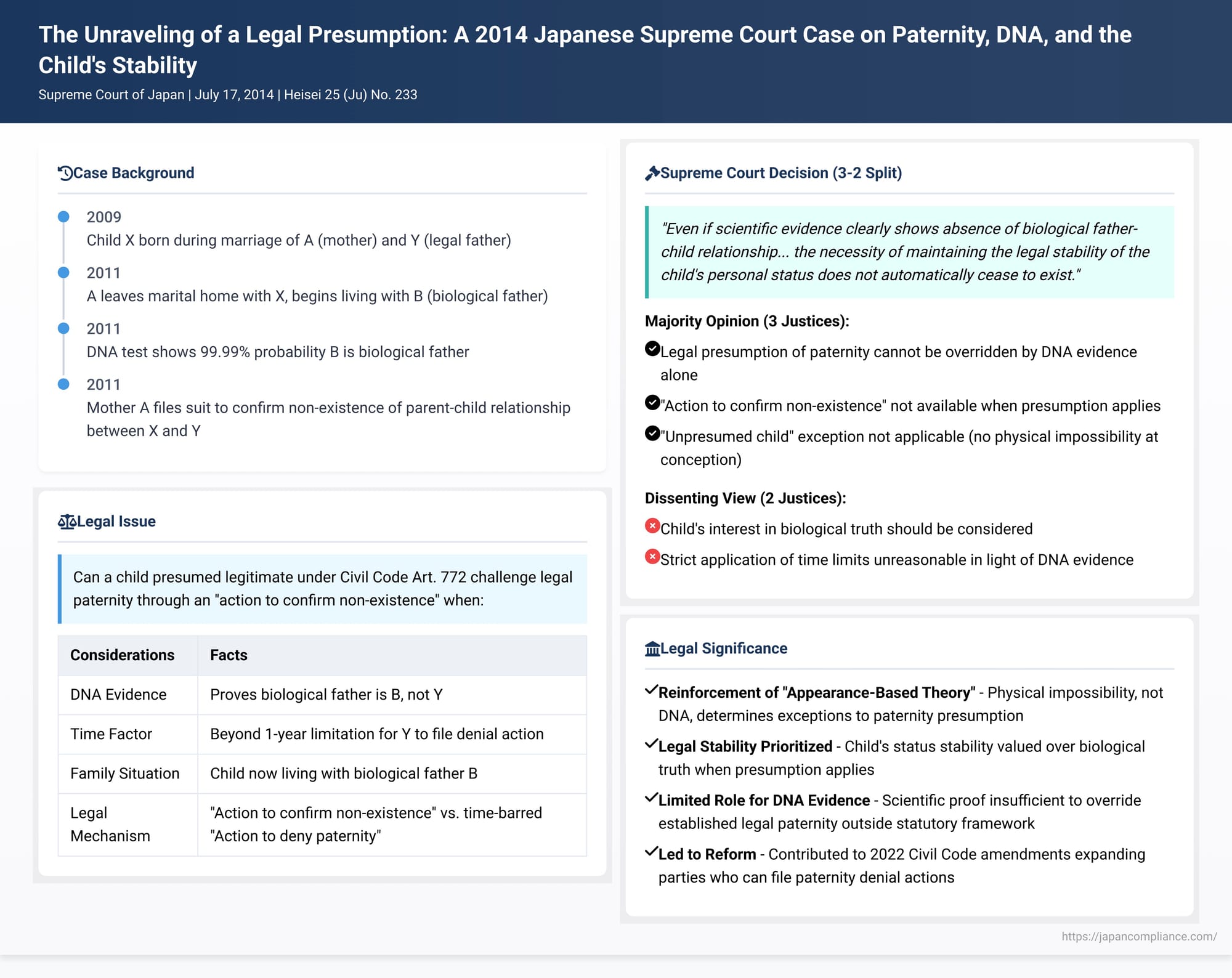

Japanese Civil Code Article 772 establishes a strong presumption of legitimacy: a child conceived by a wife during marriage is presumed to be the child of her husband. This presumption aims to provide legal stability to a child's status from birth. While the law allows a husband to challenge this presumption through an "action to deny paternity of a legitimate child" (嫡出否認の訴え - chakushutsu hinin no uttae), this action is strictly time-limited—it must be filed within one year of the husband learning of the child's birth (Article 777). But what happens when scientific evidence, such as DNA testing, definitively proves a lack of biological connection years later, and the family unit has already fractured? Can the legal parent-child relationship, founded on this now-disproven presumption, still be severed through other legal means, such as an "action to confirm the non-existence of a parent-child relationship" (親子関係不存在確認の訴え - oyako kankei fusonzai kakunin no uttae)? The Supreme Court of Japan grappled with this highly sensitive issue in a decision on July 17, 2014 (Heisei 25 (Ju) No. 233).

The Facts: A Marriage, a Child, and a Later Revelation

The case involved A (the mother) and Y (the husband), who were legally married. During their marriage, A became involved with another man, B. A subsequently gave birth to a child, X, in Heisei 21 (2009). Under Japanese law, X was presumed to be the legitimate child of A and her husband, Y. Y initially raised X as his child.

However, the marital relationship between A and Y deteriorated. In Heisei 23 (2011), A left the marital home with X and began living with B and B's two children from a previous relationship. X reportedly called B "father" and was developing well in this new family environment. A DNA test conducted privately by X's side indicated a 99.99% probability that B, not Y, was X's biological father.

In the same year (2011), A, acting as X's legal representative (as X was a minor), filed a lawsuit against Y (X's legal father) seeking a judicial confirmation of the non-existence of a legal parent-child relationship between X and Y. Subsequently, in Heisei 24 (2012), A also initiated divorce proceedings against Y.

The appellate court (Osaka High Court, November 2, 2012) had ruled in favor of X (represented by A). It found that the DNA evidence clearly showed X was not Y's biological child, Y himself was not actively disputing B's biological paternity, and X was thriving in the care of A and B. Based on these factors, the High Court concluded that "special circumstances" existed under which the presumption of legitimacy afforded by Article 772 should not apply to X, and therefore, the claim for non-existence of a parent-child relationship with Y should be granted. Y then filed a petition for acceptance of appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Prioritizing Legal Stability of Status

The Supreme Court, in a divided 3-2 decision, overturned the High Court's ruling and dismissed X's lawsuit. The majority opinion emphasized the importance of the legal stability of a child's status and upheld the strictness of the statutory system for challenging paternity.

The Court's Core Reasoning:

- Rationale for the System of Presumed Legitimacy and Limited Denial: The Court began by reaffirming the established understanding of Japan's paternity laws: "The Civil Code, by providing that a child presumed legitimate under Article 772 can only have their legitimacy denied through an action to deny paternity filed by the husband, and by stipulating a one-year period for filing such an action, can be said to possess rationality from the viewpoint of maintaining the legal stability of personal status relationships."

- Scientific Evidence and Changed Circumstances Do Not Automatically Oust the Presumption: The crux of the decision lay in addressing whether modern scientific proof of non-paternity, coupled with changed family circumstances, could override the statutory framework. The Court stated: "Even if scientific evidence clearly shows the absence of a biological father-child relationship between the husband and child, and even if the child is not currently being cared for by the husband but is growing up smoothly under the care of the wife and the biological father, the necessity of maintaining the legal stability of the child's personal status does not automatically cease to exist. Therefore, the existence of the aforementioned circumstances does not mean that the presumption of legitimacy under said article ceases to apply, and it is appropriate to construe that the existence or non-existence of the said father-child relationship cannot be contested by means of an action to confirm the non-existence of a parent-child relationship." (Underlining added by the judgment itself for emphasis).

- Reconciling with the "Child Beyond the Reach of Presumption" Doctrine (推定の及ばない子 - suitei no oyobanai ko):

The Court acknowledged a line of precedents where it had allowed the legal father-child relationship to be challenged via an action for non-existence of paternity, even outside the strictures of the action to deny paternity. This is known as the "child beyond the reach of presumption" or "unpresumed child" doctrine. This doctrine applies in cases where "regarding a child born to a wife within the period prescribed by Article 772, paragraph 2, circumstances exist such that, at the time the wife should have conceived the child, the husband and wife had already de facto divorced and the reality of their marital life was lost, or they were living far apart, and it was clear that there was no opportunity for sexual relations between them." In such situations, the child is "substantively a legitimate child to whom the presumption under said article does not apply," and thus the parent-child relationship with the husband can be contested via an action for non-existence of paternity.

However, the Supreme Court found that in the present case, there was no evidence that such circumstances (e.g., complete separation and lack of sexual opportunity at the time of X's conception) existed between A and Y. Therefore, this exception did not apply.

As a result, X's lawsuit to confirm the non-existence of a parent-child relationship with Y was deemed impermissible, as X was a child subject to the presumption of legitimacy under Article 772, and the time for Y (the husband) to file an action to deny paternity had passed.

The judgment included supplemental opinions from two justices in the majority and strong dissenting opinions from two other justices, highlighting the deep divisions within the Court on this sensitive issue.

The Significance of the Ruling: Upholding Formal Stability Over Biological Truth in Specific Contexts

This 2014 Supreme Court decision carries significant weight:

- Reinforcement of the "Appearance-Based Theory" (Gaikan-setsu): By rejecting the claim despite clear DNA evidence of non-paternity and the child living with the biological father, the Supreme Court strongly reaffirmed its traditional "appearance-based theory" for determining when a child falls outside the strict paternity presumption. This theory primarily focuses on whether it was physically impossible for the husband to be the father at the time of conception due to, for example, long-term separation or imprisonment. The mere scientific proof of non-paternity after the fact, or the current living arrangements of the child, are not sufficient to displace the legal presumption if the "appearance" of a normal marital relationship existed at the time of conception.

- Primacy of Legal Stability for Child's Status: The majority opinion repeatedly emphasized the "legal stability of the child's personal status" as the primary rationale for the restrictive nature of the paternity denial system. The idea is that once a child's legal parentage is established (even by presumption), it should not be easily overturned, as this could create uncertainty and insecurity for the child.

- Limited Role for DNA Evidence in Overturning Established Legal Paternity (Outside Denial Action): While DNA evidence is crucial in paternity disputes within the proper legal framework (e.g., in an action to deny paternity if timely filed, or in a suit to establish paternity of a non-marital child), this decision indicates that it cannot, on its own, serve as a backdoor to negate a legally presumed father-child relationship once the statutory window for denial has closed and the "appearance-based" exceptions do not apply.

Academic Perspectives and the Evolving Debate on Paternity Law

The Supreme Court's decision sparked considerable academic debate, as reflected in the dissenting opinions and subsequent legal commentary.

- The "Blood-Tie Principle" vs. Legal Stability: A central tension in paternity law is the conflict between the desire to align legal parentage with biological reality (the "blood-tie principle") and the need for legal certainty and stability in family relationships, especially for the child's welfare. The majority opinion in this case clearly prioritized legal stability achieved through the existing statutory framework over a strict adherence to biological truth in situations where the legal presumption had taken firm root.

- The Child's Right to Know Their Origins vs. Stability of Status: Dissenting opinions often emphasize the child's right to know their biological origins and to have their legal status reflect that reality, particularly when the biological father is known and willing to assume parental responsibilities and a new family unit has formed. They argue that forcing a child to remain legally tied to a non-biological father with whom they no longer live can be detrimental to their identity and well-being.

- Arguments for Expanding Exceptions: Some scholars, influenced by the increasing availability and accuracy of DNA testing, have argued for a broader interpretation of when the presumption of legitimacy can be challenged, or for legislative reform to allow for greater consideration of biological truth, especially when all parties (mother, legal father, biological father, and eventually the child) might agree or when it is clearly in the child's best interests. The argument is that the strictness of the old rules, designed in an era without reliable paternity testing, may no longer be fully appropriate.

- The Role of the Family Court: The commentary on this case and related decisions suggests that even if a formal action to confirm non-existence of paternity is dismissed, family courts in Japan sometimes use other procedural avenues or encourage settlements that pragmatically address the realities of such situations, although this is not a formal legal remedy.

The Impact of Subsequent Civil Code Reforms (Reiwa 4/2022)

It is crucial to note that Japanese parentage law underwent significant reforms enacted in Reiwa 4 (2022), which came into effect subsequently. These reforms aimed to address some of the long-standing issues related to paternity, including those highlighted by cases like this one.

- The reforms, among other things, expanded the parties who can file an action to deny paternity, now including the child and the mother, not just the husband.

- The time limit for filing such an action was also extended from one year to three years (from knowledge of birth for the father, or from birth for the child and mother, with special provisions for adult children).

These legislative changes directly address some of the procedural barriers that were central to the outcome in the 2014 Supreme Court case. While this 2014 judgment was based on the law as it stood then, the subsequent reforms indicate a legislative effort to provide more avenues for aligning legal parentage with biological reality, particularly by giving the child and mother their own standing to challenge the presumption, albeit still within a defined timeframe.

The commentary also notes that even with these reforms, the theoretical basis of the "unpresumed child" doctrine (the gaikan-setsu or appearance-based theory) related to the impossibility of conception by the husband might still hold relevance, particularly concerning the establishment of paternity without resorting to the formal denial process. The precise interplay between the reformed denial system and the existing case law on "unpresumed children" continues to be a subject of legal analysis.

Conclusion: A Balancing Act Between Legal Certainty and Biological Truth

The Supreme Court's 2014 decision underscored the high value placed on the legal stability of a child's status under the then-existing Japanese Civil Code. It affirmed that even clear scientific evidence of non-paternity and the formation of a new family unit with the biological father were not, by themselves, sufficient grounds to allow a presumed legitimate child to challenge their legal relationship with their legal father outside the strict statutory framework for denying paternity, unless specific "appearance-based" circumstances (like impossibility of conception by the husband) were present at the time of conception.

While this ruling prioritized legal certainty, it also highlighted the emotional and practical complexities that arise when legal presumptions diverge from biological and social realities. The strong dissenting opinions and subsequent legislative reforms demonstrate an ongoing societal and legal effort to find a more nuanced balance between the need for stable family statuses and the importance of biological truth and individual well-being in matters of parentage.