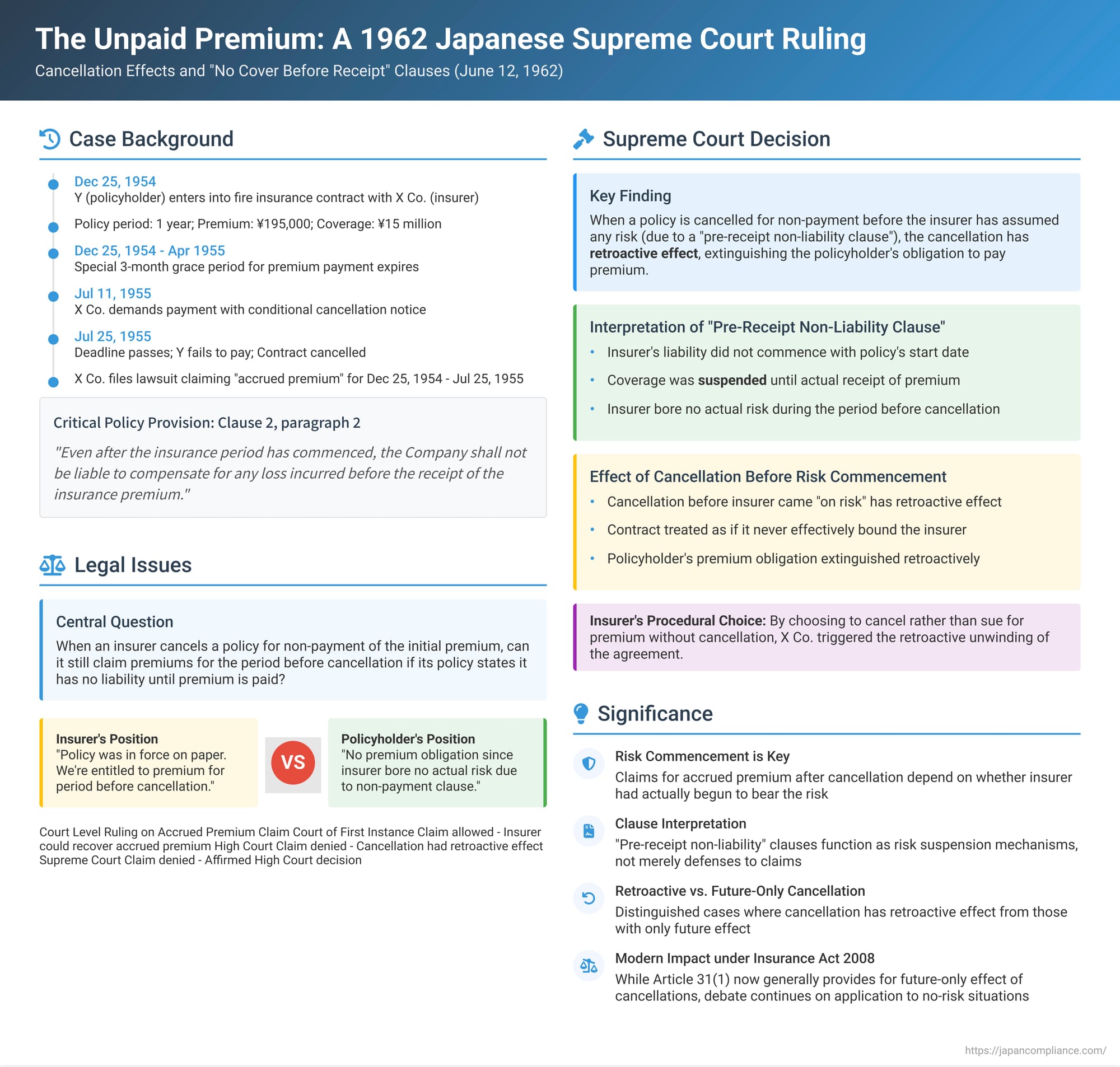

The Unpaid Premium: A 1962 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Cancellation Effects and "No Cover Before Receipt" Clauses

Judgment Date: June 12, 1962

Court: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench

Case Name: Fire Insurance Premium Claim Case

Case Number: Showa 34 (O) No. 355 of 1959

Introduction: The Premium-Protection Nexus in Insurance

The core of an insurance contract is a reciprocal agreement: the policyholder pays a premium, and the insurer provides protection against specified risks. But what unfolds if this fundamental exchange breaks down, specifically, if the policyholder fails to pay the agreed-upon premium? While insurers generally have the right to cancel a policy for non-payment, a crucial question arises regarding the policyholder's obligation for premiums that may have technically "accrued" during the period the policy was nominally in force but before the insurer had actually assumed any risk, particularly when the policy contains clauses limiting liability prior to premium receipt.

This complex interplay of contractual obligations, risk assumption, and the effects of cancellation was at the heart of a significant 1962 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan. The case explored whether an insurer, after cancelling a fire insurance policy due to non-payment of the initial premium, could still demand payment for the portion of the policy period that had elapsed before cancellation, especially when the policy stipulated no liability before the premium was received.

The Factual Scenario: A Policy Formed, A Premium Unpaid

The dispute involved Mr. Y, a policyholder, and X Co., an insurance company. On December 25, 1954, Y entered into a fire insurance contract with X Co. to insure his residential and commercial building for a sum of 15 million yen. The policy period was set for one year from that date, with a total premium of 195,000 yen.

The contract was based on X Co.'s standard fire insurance policy terms and conditions. A critical provision, Clause 2, paragraph 2, stated: "Even after the insurance period has commenced, the Company shall not be liable to compensate for any loss incurred before the receipt of the insurance premium". This is commonly referred to as a "pre-receipt non-liability clause" or "領収前免責条項" (ryōshūzen menseki jōkō).

Despite the policy's commencement, Y failed to pay the insurance premium. This non-payment persisted even after a three-month grace period, which had been specially agreed upon, had expired. Consequently, on July 11, 1955, X Co. formally demanded that Y pay the outstanding premium. This demand was coupled with a conditional notice of cancellation: if Y did not remit the premium by July 25, 1955, X Co. would cancel the insurance contract. Y still did not pay the premium, and the cancellation thus took effect.

Following the cancellation, X Co. initiated a lawsuit against Y. The insurer sought to recover the portion of the premium that corresponded to the period from the inception of the policy (December 25, 1954) up to the date of its cancellation (July 25, 1955) – often termed the "accrued premium" or "既経過保険料" (kikeika hokenryō).

The Legal Journey: From Trial Court to Supreme Court

The case navigated through the Japanese court system with differing outcomes:

- Court of First Instance: The initial trial court found in favor of the insurer, X Co. It ordered Y to pay the accrued premium for the period the policy was deemed to have been in effect before cancellation.

- Appellate Court (Fukuoka High Court): Y appealed this decision. The High Court reversed the trial court's ruling, finding in favor of the policyholder, Y. The appellate court's reasoning was that Clause 2, paragraph 2 (the pre-receipt non-liability clause) meant that X Co. had not actually borne any insurance responsibility from the policy's start, as the premium had never been paid. Therefore, when X Co. cancelled the contract for non-payment, the cancellation was deemed to have retroactive effect, effectively nullifying any obligation on Y's part to pay the premium for that period.

X Co., the insurer, then appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (June 12, 1962): Upholding No Claim for Accrued Premium

The Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, dismissed X Co.'s appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's judgment that the insurer could not claim the accrued premium from Y under these specific circumstances. The Court's reasoning was multifaceted:

Insurer's Right to Cancel for Non-Payment

The Court first acknowledged the insurer's general right to cancel an insurance contract due to the policyholder's failure to pay premiums. It clarified that this right stemmed from general principles of contract law (specifically, Article 541 of the Civil Code, which permits a party to cancel a contract upon the other party's breach of obligation), and was distinct from other specific grounds for cancellation provided in the Commercial Code at the time (such as for misrepresentation by the insured, insurer's bankruptcy, or certain increases in risk).

Interpretation of the "Pre-Receipt Non-Liability Clause" (Clause 2, para 2)

The interpretation of this clause was pivotal to the Supreme Court's decision. The Court construed Clause 2, paragraph 2 to mean that the insurer's legal responsibility to provide coverage and pay for losses did not actually commence with the start date of the insurance period if the premium had not been paid. Instead, the insurer's liability was effectively suspended and would only begin upon the actual receipt of the premium. Even though the policy term might have started on paper, the substantive obligation of the insurer to cover risks had not yet been triggered due to Y's non-payment.

Effect of Cancellation in This Context

Given this interpretation, the Supreme Court reasoned as follows regarding the effect of X Co.'s cancellation:

- Cancellation Before Risk Commencement: Because X Co.'s liability under the policy had not yet begun (due to the non-receipt of the premium, as dictated by Clause 2, paragraph 2), the cancellation for non-payment was, in essence, a cancellation that occurred before the insurer had effectively come on risk.

- Retroactive Effect of Cancellation: In such a scenario—where the insurer cancels the contract before its own risk-bearing obligations have commenced—the cancellation has retroactive effect. This means the contract is treated, for the purposes of the insurer's liability and the policyholder's corresponding premium obligation, as if it never effectively bound the insurer to cover any risk during that period.

- Extinguishment of Premium Obligation: Consequently, if the contract is unwound retroactively with respect to the insurer's assumption of risk, the policyholder's obligation to pay the premium for this "uncovered" period is also extinguished retroactively. X Co. could not claim payment for a period during which it was not, in substance, providing any insurance protection.

X Co.'s Choice to Cancel

The Supreme Court also highlighted the procedural choice made by X Co.. It pointed out that X Co. arguably had the option to sue Y for the outstanding premium without cancelling the contract (though the practical value of this, given Clause 2, paragraph 2, remained complex). By instead choosing to demand payment, issue a conditional cancellation notice, and then treat the contract as lapsed due to that cancellation, X Co. itself initiated the termination of the agreement under which it had, per its own clause, borne no actual risk. In these specific circumstances, the Court concluded that the cancellation could not be construed as a mere "解約告知" (kaiyaku kōkoku)—a termination notice having only future effect—which might have preserved a claim for premiums accrued for past coverage.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court found no error in the High Court's reasoning that supported dismissing X Co.'s claim for the accrued premium and thus dismissed the insurer's appeal.

Analysis and Implications of the 1962 Ruling

This 1962 Supreme Court judgment remains a significant case in Japanese insurance law, particularly for its exploration of the consequences of non-payment of premiums when specific policy clauses limit pre-receipt liability.

1. The Crucial Role of "Risk Commencement":

The decision underscores that the question of whether an insurer can claim accrued premiums after cancellation for non-payment heavily depends on whether the insurer had actually begun to bear the insured risk. If risk has not substantively commenced from the insurer's perspective, the Court found that retroactive cancellation (and thus no entitlement to "earned" premium for that period) is a logical and fair outcome. Conversely, had the insurer been on risk, the argument for cancellation having only future effect (allowing the insurer to claim premiums for the period coverage was provided) would have been much stronger.

2. The "Pre-Receipt Non-Liability Clause" as a Risk Suspension Mechanism:

The Court's interpretation of the common "pre-receipt non-liability clause" as one that effectively suspends the commencement of the insurer's actual liability until the premium is paid was a key determinant. This view, treating the clause not just as a defense to a claim but as a condition precedent to the insurer's assumption of risk, was shared by many legal scholars at the time.

3. Retroactive vs. Future-Only Cancellation in Insurance Contracts:

The case touches upon a broader legal debate regarding the effects of contract cancellation. While the general principle for cancellation due to breach under the Japanese Civil Code (Art. 545(1)) is retroactive effect, "continuous contracts" (like leases or employment agreements, and arguably insurance) often see cancellations with only future effect to avoid the impracticality of unwinding past performance. The old Commercial Code did specify future-only effects for certain types of insurance cancellations (e.g., due to policyholder misrepresentation or insurer bankruptcy). However, the Supreme Court in this 1962 ruling did not extend a blanket future-only principle to all insurance cancellations. Specifically, for non-payment of premiums where the insurer, due to a clause like Clause 2, para 2, had not assumed any risk, the Court found retroactivity to be appropriate.

4. The Impact of the Three-Month Grace Period:

An interesting, though undeveloped, aspect of the case was the three-month grace period for premium payment that Y had received. The PDF commentary suggests that if this grace period had been argued and proven in the lower courts to be a "責任持ち特約" (sekinin-mochi tokuyaku)—a special agreement whereby the insurer agreed to be on risk during those three months even without premium payment (effectively waiving or modifying Clause 2, para 2 for that duration)—the entire premise of "no risk had commenced" would have been undermined. This could have potentially led to a different outcome, as the cancellation might then have been viewed as occurring after the insurer's risk had begun. However, this point was not sufficiently litigated for the Supreme Court to base its decision on it.

5. The Legal Landscape Following the Insurance Act of 2008:

It is crucial to view this 1962 judgment in the context of subsequent major reforms to Japanese insurance law, particularly the enactment of the Insurance Act of 2008. Article 31, paragraph 1 of this Act now generally provides that the cancellation of a non-life insurance contract has future effect only. This provision is "unilaterally mandatory," meaning it cannot be varied by contract to the detriment of the policyholder.

On its face, this statutory change appears to directly conflict with the 1962 Supreme Court's finding of retroactive effect for a non-payment cancellation. However, legal scholarship continues to debate the precise scope of Article 31(1) in situations mirroring the 1962 case. Some argue that if, due to a "pre-receipt non-liability clause," the insurer’s protection never actually commenced for the policyholder, there is no "accrued insurance protection" for the policyholder that needs to be shielded from retroactive termination. In such a specific scenario, the policyholder might not be disadvantaged by a retroactive cancellation (which would relieve them of premium obligations for a period they received no actual coverage), and thus the rationale for the mandatory future-only effect might not strictly apply, or the outcome of the 1962 case (no premium due) might still be reached through other reasoning.

6. Modern Insurance Policy Drafting:

Contemporary insurance policies in Japan often address the issue of non-payment more explicitly. It's common for policies to state that if a premium (whether the initial one or subsequent installments) is not paid by the end of a specified grace period, not only is the insurer not liable for any losses occurring after the premium due date, but the cancellation itself can be made retroactive to that premium due date. Such clauses are generally considered valid under the Insurance Act of 2008, as they do not typically disadvantage a policyholder who was, in effect, not receiving insurance coverage for the period in question. This contractual approach often leads to a similar practical outcome as the 1962 Supreme Court decision—the insurer cannot claim premiums for a period where no risk was actually borne due to non-payment and the effect of specific policy terms.

Conclusion

The 1962 Supreme Court decision in Chiyoda Fire & Marine Insurance Co., Ltd. v. Miki provides a foundational understanding of how Japanese law, at that time, treated the cancellation of an insurance policy for non-payment of the initial premium when a "pre-receipt non-liability clause" was in effect. The Court’s core finding was that if such a clause effectively suspends the insurer's assumption of risk until the premium is paid, a cancellation by the insurer for non-payment before any premium is received results in the cancellation having retroactive effect. This, in turn, extinguishes the policyholder's obligation to pay premiums for the period during which the insurer had not actually commenced its risk-bearing duties.

While the subsequent enactment of the Insurance Act of 2008, particularly its provisions on the future-only effect of cancellations, has modified the broader legal landscape, this 1962 ruling remains a significant reference point. It highlights the critical importance of specific policy wording, the concept of when an insurer truly comes "on risk," and the fundamental principle that an insurer is generally not entitled to premiums for periods where it provided no substantive coverage due to the policyholder's non-payment and the operation of clauses like the "pre-receipt non-liability clause." The case continues to inform discussions on the intricate balance of rights and obligations between insurers and policyholders concerning premium payment and contract continuity.