The Unpaid Installment: A 1997 Japanese Supreme Court Case on Burden of Proof and Reinstated Insurance Cover

Judgment Date: October 17, 1997

Court: Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench

Case Name: Insurance Claim Case

Case Number: Heisei 8 (O) No. 2064 of 1996

Introduction: The Perils of Missed Premiums and Uncertain Timings

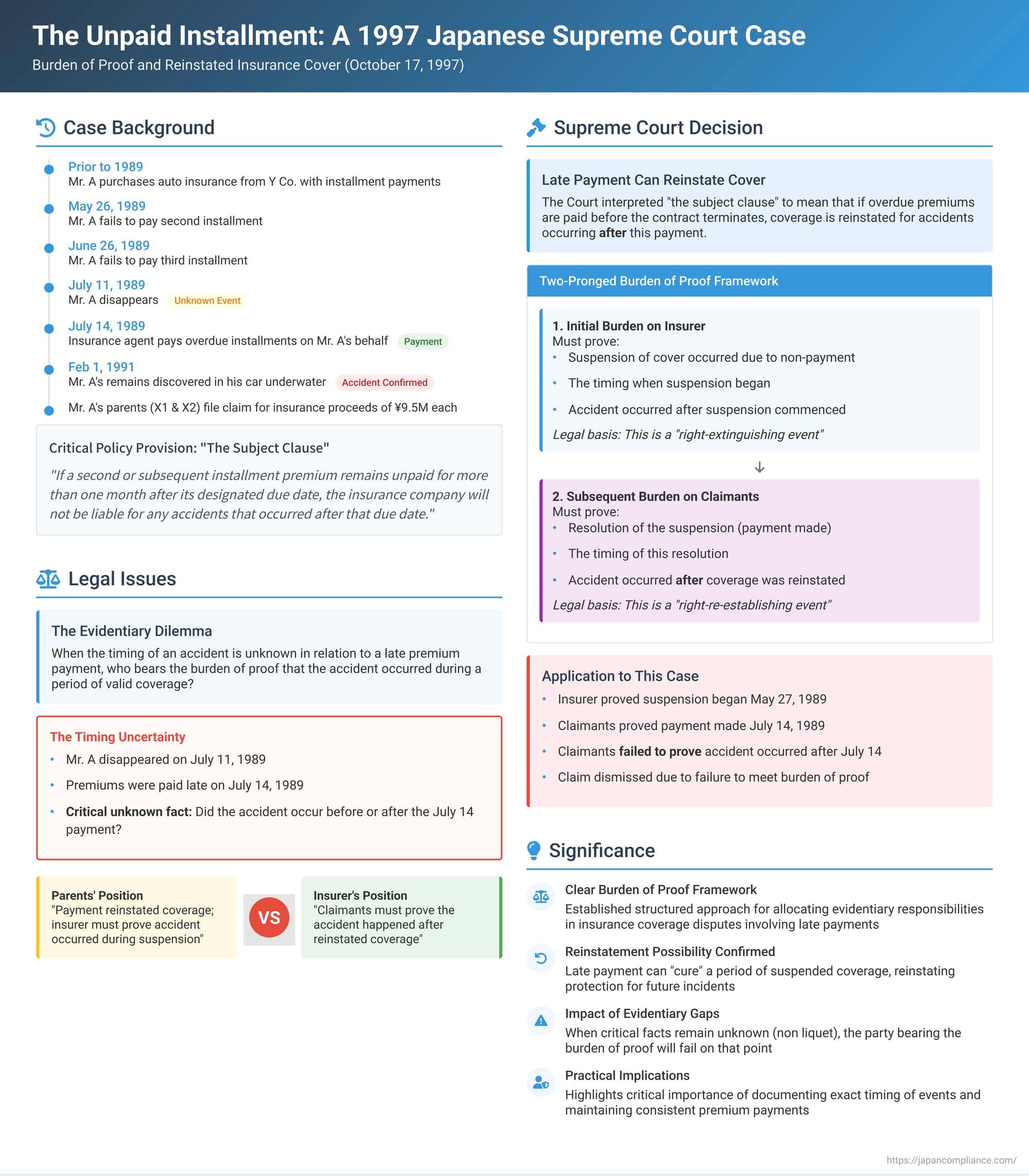

Paying insurance premiums in installments can make coverage more financially accessible for policyholders. However, this mode of payment introduces complexities, particularly if an installment is missed. Typically, insurance policies stipulate that coverage may be suspended or "lapse" if premiums are not paid by their due date or within a specified grace period. A critical question then arises: what happens if the overdue premium is subsequently paid, potentially reinstating the coverage, but an accident occurs around the same time, and its precise timing relative to the payment and reinstatement is unknown?

This intricate issue of who bears the legal responsibility – the burden of proof – to demonstrate that the accident occurred during a period of valid, reinstated coverage was at the heart of a pivotal 1997 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan. The case involved a fatal car accident where the timing of the incident in relation to a late premium payment was shrouded in uncertainty, forcing the Court to delineate clear rules on which party must prove the crucial sequence of events.

The Factual Predicament: A Disappearance, An Unpaid Premium, and an Untimed Accident

The case centered on Mr. A, who had taken out an automobile insurance policy with Y Company. The policy premiums were structured with an initial down payment, followed by monthly installments. Mr. A duly paid the down payment at the time the contract was concluded. However, he failed to pay the second installment, due on May 26, 1989, and the third installment, due on June 26, 1989.

The automobile insurance policy contained a crucial clause (referred to as "the subject clause"). This clause specified that if a second or subsequent installment premium remained unpaid for more than one month after its designated due date, the insurance company (Y Company) would not be liable for any accidents that occurred after that due date. This effectively created a period during which insurance coverage would be suspended due to non-payment.

Tragically, Mr. A disappeared on the evening of July 11, 1989. Shortly thereafter, on July 14, 1989, Mr. B, who was Y Company's insurance agent and had handled the original policy for Mr. A, paid the principal amount of Mr. A's overdue installments (for May, June, and July) to Y Company on Mr. A's behalf.

Almost two years later, on February 1, 1991, Mr. A's skeletal remains were discovered inside his insured vehicle at the bottom of the sea. It was determined that he had died as a result of an accident involving the operation of the insured vehicle. While it was certain that this fatal accident had occurred on or after his disappearance on July 11, 1989, the exact date and time of the accident after that point could not be established.

Mr. A's parents, X1 and X2, as his legal heirs, subsequently filed a claim with Y Company for the insurance proceeds under his policy, seeking 9.5 million yen each. Y Company presumably denied the claim based on the uncertainty surrounding the timing of the accident relative to the premium payment and the period of suspended cover.

The Core Legal Issue: The Burden of Proof in an Evidentiary Void

The central legal battle revolved around a critical question of evidence and procedural law: when the precise timing of an insured event (the accident) is unknown, but it is known to have occurred around a period of premium default and subsequent late payment, who bears the legal burden of proving that the accident fell within a period when the insurance coverage was actually in force?

Would the insurer, Y Company, have to prove that the accident occurred during the "suspension of cover" period (i.e., before the late premium payment on July 14, 1989, but after the grace period for the May installment had expired)? Or would the claimants, X1 and X2, have to prove that the accident occurred after the late premium payment had been made and coverage potentially reinstated? The answer to this question of allocating the burden of proof would be determinative of the case's outcome, given the evidentiary void regarding the accident's exact timing.

Lower Court Decisions

Both the court of first instance and the subsequent appellate court dismissed the claims brought by X1 and X2. These decisions implicitly or explicitly placed the crucial burden of proving that the accident occurred during a period of effective coverage onto the claimants.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (October 17, 1997): Allocating the Burden

The Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, ultimately upheld the lower courts' dismissal of the claim but provided a detailed and structured reasoning for allocating the burden of proof.

Effect of Late Payment (Reinstatement of Cover)

Before addressing the burden of proof, the Court first interpreted the meaning and effect of "the subject clause" concerning non-payment and subsequent late payment of installment premiums.

It held that the clause should be understood to mean that even if a "suspension of cover state" (hoken kyūshi jōtai) arose due to the policyholder's failure to pay an installment premium for more than one month, if the full principal amount of all overdue installments was subsequently paid to the insurance company before the insurance contract itself terminated, this payment would resolve the suspension. Consequently, the insurance company would then be liable for insurance accidents that occurred after this resolving payment was made.

The rationale provided by the Court for this interpretation was that the primary purpose of such a non-liability clause is to impose a sanction for late payment, thereby securing the insurer's premium income and avoiding the unfair situation where an insurer might have to pay a claim despite not having received the corresponding premium. However, once the overdue premium is indeed paid, the justification for this sanction disappears. In such circumstances, recognizing the re-emergence of the insurer's payment obligation for future events is consistent with principles of fairness and aligns with the presumed ordinary intentions of the contracting parties.

The Two-Pronged Burden of Proof

Having established that late payment could reinstate cover for future incidents, the Supreme Court then laid out a clear, sequential allocation of the burden of proof:

- Burden on the Insurer (Y Company):

To establish its initial defense (i.e., that coverage was suspended and therefore it was not liable), the insurer must assert and prove the following:- The occurrence of the "suspension of cover state" due to the policyholder's failure to pay the installment premium beyond the one-month grace period.

- The specific timing when this suspension of cover began.

- That the insured accident occurred after this suspension of cover had commenced.

The Court reasoned that the insurer bears this burden because the commencement of a "suspension of cover state" is legally characterized as a "right-extinguishing event" concerning the insured's potential claim for insurance benefits. Established principles of procedural law place the burden of proving such a right-extinguishing event on the party who asserts it (in this case, the insurer).

- Burden on the Claimants (X1 and X2):

If the insurer successfully meets its initial burden, then, to overcome this and establish that coverage was in fact reinstated and applicable to their loss, the claimants must assert and prove the following:- The resolution of the "suspension of cover state," typically by demonstrating that the overdue premiums were paid.

- The specific timing of this resolution (i.e., the date of payment).

- Crucially, that the insured accident occurred after the cover was reinstated by this payment.

The Court justified this by characterizing the resolution of the suspension state and the subsequent re-emergence of the insurer's liability as a "right-re-establishing event" for a right that had previously been extinguished or suspended. The burden of proving such a right-re-establishing event falls upon the party who stands to benefit from it (in this case, the claimants).

Application to the Facts and Outcome

Applying this framework to the specific facts of Mr. A's case:

- Y Company (the insurer) successfully met its initial burden. It demonstrated that Mr. A had failed to pay the May 1989 installment, and thus a "suspension of cover state" had commenced on May 27, 1989 (one month after the May 26 due date, as per common interpretation of such clauses, although the judgment text uses this date as the start of the suspension period directly). It was also proven that Mr. A's fatal accident occurred sometime on or after July 11, 1989, which was clearly after the suspension of cover had begun on May 27, 1989.

- The overdue premiums were indeed paid by Mr. B on July 14, 1989. This payment resolved the "suspension of cover state" from that point forward, meaning coverage was potentially reinstated for accidents occurring thereafter.

- However, X1 and X2 (the claimants) were unable to prove that Mr. A's fatal accident occurred after this crucial payment on July 14, 1989. The evidence only established that the accident happened sometime on or after July 11, 1989. It could have occurred on July 11, 12, or 13 (during the suspension period, before the payment), or it could have occurred on or after July 14 (during a period of potentially reinstated cover). This critical timing remained unknown.

- Since the exact timing of the accident relative to the July 14 payment could not be proven by the claimants, they failed to meet their allocated burden of proof.

Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that the lower courts' decisions to dismiss X1 and X2's claim were correct, and it dismissed their appeal.

Analysis and Implications of the Ruling

The 1997 Supreme Court decision offers significant guidance on handling insurance claims complicated by late installment payments and uncertain accident timings.

1. Confirmation of Reinstatement Possibility:

The judgment positively affirms that, under typical installment premium policy terms, the payment of overdue premiums can indeed "cure" a period of lapsed or suspended coverage, thereby reinstating the policy for accidents that occur subsequent to such payment. This provides a path for policyholders to restore their protection after a default.

2. The "Split" Burden of Proof Framework:

The decision's most notable contribution is its clear and sequential allocation of the burden of proof. This "split" burden – where the insurer must first prove the suspension and that the accident fell generally within that suspended timeframe, and then the claimant must prove resolution and that the accident occurred specifically after reinstatement – provides a structured approach for courts to follow. This framework is rooted in established legal theories classifying different types of legal facts and their corresponding evidentiary responsibilities.

3. The Impact of Evidentiary Gaps ("Non Liquet"):

This case starkly illustrates how critical evidentiary gaps can be. When a crucial fact, such as the precise timing of an accident relative to a premium payment that reinstates cover, remains unknown or unproven (non liquet), the party who bears the burden of proving that fact will ultimately fail on that point, often leading to the failure of their claim or defense.

4. Underlying Rationales for Burden Allocation:

While the Court's primary justification was based on the legal characterization of "right-extinguishing" and "right-re-establishing" events, the PDF commentary associated with this case suggests other potential underlying considerations for placing the final burden on the claimant in these installment scenarios. These include the idea that reinstatement is an exception to the general rule of non-coverage during default, and that information regarding premium payments and accident occurrences might often be considered more within the policyholder's sphere of knowledge or access (though this was complicated in the instant case by Mr. A's death).

5. Potential Tension with Lump-Sum/First Installment Non-Payment Scenarios:

The commentary also highlights an interesting point of comparison with cases involving non-payment of a lump-sum premium or the very first installment of a policy. In such cases, a 1962 Supreme Court decision (the subject of a previous discussion, see Chiyoda Fire & Marine Insurance Co., Ltd. v. Miki, Showa 34 (O) No. 355) suggested that non-payment prevents the insurer's liability from commencing at all. Despite this, some lower court decisions and academic theories have argued that even in those "no commencement of cover" scenarios, the insurer should bear the burden of proving that an accident happened during the period of delinquency.

This raises a potential inconsistency: if a fundamental failure to pay (no first premium) might see the insurer bearing a key burden, why does a failure to pay a subsequent installment (as in this 1997 case, arguably a less absolute default once a contractual relationship has been established and initial payments made) lead to the crucial burden of proving post-reinstatement timing falling on the claimant? The commentary speculates that the clear stance in the 1997 ruling might eventually lead the Supreme Court to create more consistent burden of proof rules across different non-payment scenarios, possibly by placing the burden more uniformly on claimants to prove that an accident occurred during a period of effective coverage once any premium delinquency has been rectified, though this remains an area of ongoing legal discussion.

6. Practical Considerations for Policyholders and Insurers:

This Supreme Court decision underscores the paramount importance for policyholders of ensuring timely and consistent payment of all insurance premium installments to avoid any ambiguity or suspension of their coverage. For insurers and their agents, the case emphasizes the need for clear policy language regarding the consequences of missed payments, the conditions for reinstatement, and robust record-keeping of payment dates. In the unfortunate event of an accident occurring near a period of policy lapse and subsequent reinstatement, meticulous documentation of the exact time of all relevant events (premium payment, accident occurrence) becomes absolutely critical for all parties involved.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1997 judgment provides a definitive framework for allocating the burden of proof when the timing of an insured event is uncertain relative to the payment of overdue installment premiums and the potential reinstatement of coverage. By ruling that after the insurer establishes an initial period of suspended cover due to non-payment, the claimant then bears the responsibility of proving that the overdue premiums were paid and that the accident occurred after this reinstatement, the Court placed a significant evidentiary onus on those seeking to benefit from the revived policy.

This decision brings a measure of clarity to a complex area of insurance law, aiming to balance the insurer's right to receive timely premiums against the policyholder's ability to rectify a payment default. However, it also serves as a stark reminder that in situations where crucial facts cannot be definitively proven, the legal allocation of the burden of proof can be the decisive factor in the outcome of an insurance claim.