The Unforeseen Consequence: A Deep Dive into a Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Case on Bodily Injury Resulting in Death

Decision Date: February 26, 1957

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

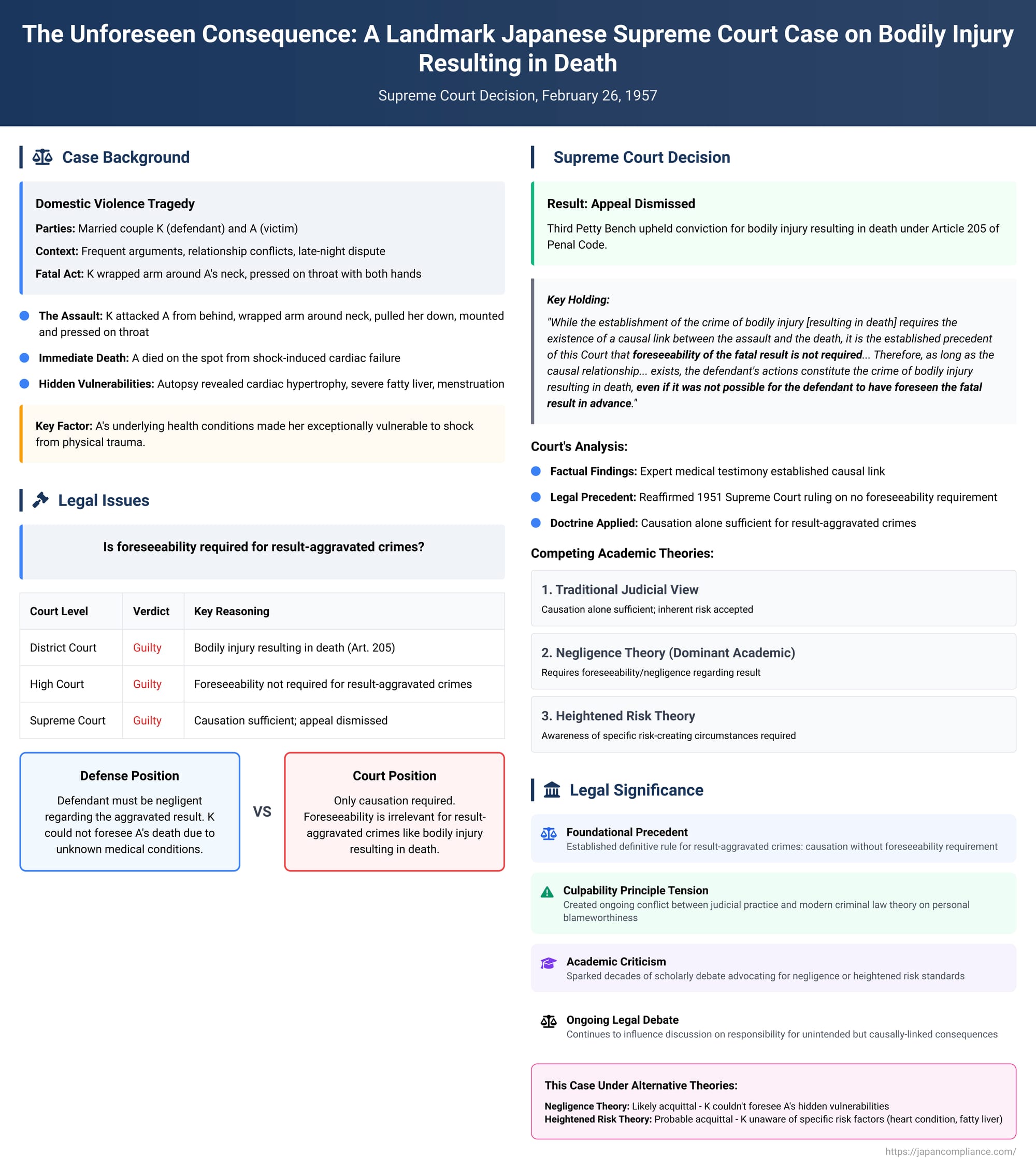

In the annals of Japanese criminal law, certain cases stand out not merely for their factual circumstances, but for the profound legal questions they force to the forefront. The Supreme Court decision of February 26, 1957, is one such case. It revolves around a domestic dispute that ended in a tragic and unintended death, thereby compelling the Japanese judiciary to confront a foundational principle of criminal liability: to what extent should an individual be held responsible for a severe consequence they did not foresee?

The case provides a critical lens through which to examine the Japanese legal doctrine of "result-aggravated crimes" (kekkateki-kajuhan), a category of offenses where a basic criminal act leads to a more serious, unintended outcome, resulting in a significantly heavier penalty. This ruling solidified a judicial stance that has been the subject of intense academic debate for decades, pitting the practical need for accountability against the modern criminal law principle that one should only be punished for what one is truly culpable.

Factual Background

The case involved a married couple, K (the defendant) and A (the victim). Their relationship was fraught with conflict, marked by frequent arguments stemming from personality clashes, to the point where divorce had become a topic of discussion.

On the day of the incident, A returned home late at night, sparking another heated argument with K. Enraged by A's demeanor, K approached her from behind, wrapped his left arm around her neck, and attempted to pull her down. A resisted, trying to break free and stand up. In response, K escalated his assault. He forcefully wrapped his arm around her neck again, pulled her to the floor in a supine position, mounted her, and pressed on her neck with both hands.

Tragically, A died on the spot. An autopsy later revealed that A had several underlying health conditions that made her exceptionally vulnerable. She suffered from cardiac hypertrophy (an enlarged heart) and severe fatty liver disease. Furthermore, she was menstruating at the time of the assault, a factor which can, in some physiological contexts, heighten susceptibility to shock. The cause of death was determined to be shock, directly induced by the physical trauma of K's assault acting upon her uniquely vulnerable physical state.

Lower Court Proceedings

The case first went to the Hachioji Branch of the Tokyo District Court. The court found K guilty of "bodily injury resulting in death" under Article 205 of the Japanese Penal Code. It determined that K's violent act was the direct cause of A's death and sentenced him to two years of imprisonment, suspended for three years.

K appealed this decision to the Tokyo High Court. The High Court upheld the lower court's ruling, dismissing the appeal. It affirmed the causal link between K's assault and A's death. Crucially, the High Court articulated a key legal position: for a conviction of a result-aggravated crime like bodily injury resulting in death, the foreseeability of the aggravated result (i.e., death) is not a required element. As long as the basic act of assault was intentional and it caused the death, the defendant was liable for the graver offense.

Dissatisfied, K's defense counsel appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan, arguing that for a result-aggravated crime to be established, the defendant must have been at least negligent with respect to the occurrence of the severe result. They contended that K could not have predicted that his actions would lead to A's death, especially given her unknown, peculiar physical conditions.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, delivered its judgment on February 26, 1957, dismissing the final appeal and cementing the lower courts' rulings.

The Court's reasoning methodically dismantled the defense's arguments. It first confirmed that the finding of facts by the lower courts was based on sufficient evidence, including expert medical testimony, and not solely on the defendant's confession.

The core of the judgment, however, addressed the central legal question: the role of foreseeability in result-aggravated crimes. The Court unequivocally stated:

"The original judgment, based on the expert opinion... found that the defendant's act of violence, the compression of A's neck, was an indirect trigger that induced her death by shock, and it is clear from the record that a causal relationship, albeit indirect, was recognized... And, while the establishment of the crime of bodily injury [resulting in death] requires the existence of a causal link between the assault and the death, it is the established precedent of this Court that foreseeability of the fatal result is not required (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, Judgment of September 20, 1951...). Therefore, as long as the causal relationship as found in the original judgment exists, it goes without saying that the defendant's adjudicated actions constitute the crime of bodily injury resulting in death, even if it was not possible for the defendant to have foreseen the fatal result in advance."

With this statement, the Supreme Court reaffirmed a long-standing and unbroken line of precedent stretching back to the pre-war Supreme Court (the Dai-shin'in). The rule was simple and stark: causation is sufficient. If an intentional basic crime (like assault) leads to a graver result (like death), the perpetrator is liable for that graver result, regardless of whether they foresaw or could have foreseen it.

Analysis: The Doctrine of Result-Aggravated Crimes and the Culpability Debate

The 1957 Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone for understanding the Japanese legal system's approach to unintended consequences. It highlights a significant tension between judicial tradition and the core tenets of modern criminal law theory.

Defining Result-Aggravated Crimes (Kekkateki-Kajuhan)

Result-aggravated crimes are a specific category in the Japanese Penal Code. They are structured as follows:

- A "basic offense" is committed intentionally (e.g., assault, unlawful confinement, rape).

- This intentional act causes an unintended, more severe "aggravated result" (e.g., injury or death).

- The law prescribes a significantly heavier punishment for this combined event than for the basic offense alone.

The crime of bodily injury resulting in death (Article 205) is a classic example. The basic offense is bodily injury (Article 204). If that injury leads to the victim's death, the penalty is elevated from "imprisonment with work for not more than 15 years or a fine of not more than 500,000 yen" to "imprisonment with work for a definite term of not less than 3 years," a penalty range comparable to that for homicide. The question is, what justifies this substantial increase in punishment?

The Traditional Judicial Approach: Causation is King

As the 1957 ruling makes clear, the consistent position of the Japanese courts has been that the only necessary link between the intentional basic act and the aggravated result is causation. The logic, though not always explicitly stated in judgments, appears to be that certain acts, like assault, are inherently dangerous and carry a general risk of causing severe harm. The law, by creating the category of result-aggravated crimes, is deemed to have already factored in this inherent risk. Therefore, anyone who intentionally commits the basic offense is considered to have accepted the risk of any and all consequences that causally flow from it. In this view, inquiring into the defendant's personal foresight is unnecessary.

This approach has been applied consistently across various result-aggravated crimes, including in cases where, like the present one, the victim's hidden vulnerability was a major contributing factor to the fatal outcome.

The Clash with the Principle of Culpability

This judicial stance faces strong criticism from the majority of Japanese legal scholars. The primary objection is that it violates the principle of culpability (sekinin shugi), a cornerstone of modern criminal law akin to the maxim nulla poena sine culpa ("no punishment without guilt"). This principle holds that a person should only be punished for actions and consequences for which they are mentally blameworthy.

Punishing a defendant for an unforeseen and unforeseeable result is, in essence, an application of "liability for the result" (kekka sekinin), which is a form of strict liability. Critics argue that this is a relic of an older, more primitive conception of justice and is incompatible with a legal system that purports to punish based on the actor's guilty mind, not just the outcome. If K could not have reasonably foreseen that his assault would kill A due to her unknown medical conditions, holding him liable for her death (and punishing him far more severely for it) seems to punish him for bad luck rather than for a higher degree of culpability.

Academic Efforts to Reconcile the Doctrine

The academic world in Japan has largely agreed that the courts' approach is problematic and requires modification to align with the principle of culpability. The debate, however, rages on as to how this reconciliation should be achieved.

1. The Dominant Academic View: Requiring Negligence

The prevailing theory among legal scholars is that, in addition to causation, there must be negligence (kashitsu) on the part of the defendant with respect to the aggravated result. This means the result must have been reasonably foreseeable to the defendant.

Under this model, a result-aggravated crime is seen as a hybrid of an intentional crime and a negligent crime. The defendant is guilty of intentionally committing the basic offense (assault) and negligently causing the aggravated result (death). This approach would bring the doctrine in line with the principle of culpability by ensuring that the defendant is only held responsible for a result they could and should have anticipated.

However, this theory is not without its own difficulties. A key challenge is that it doesn't fully explain the punitive structure of these crimes. If bodily injury resulting in death is merely a combination of intentional injury and negligent homicide, why is its statutory penalty significantly higher than the penalties for those two crimes simply added together? This suggests that the law views the result-aggravated crime as something more than a mere composite, a point the negligence theory struggles to rationalize completely.

2. A More Recent Theory: The "Heightened Risk" Approach

In recent decades, an influential new theory has emerged that seeks to locate the justification for the heavier punishment in the specific nature of the risk created by the defendant's actions.

This view posits that result-aggravated crimes are established when the defendant's intentional basic act creates a "particularly high degree of risk" of the aggravated result occurring. The heightened culpability, and thus the heavier punishment, stems not just from causing the result, but from creating this specific, elevated danger through one's intentional conduct.

Crucially, this theory requires a subjective element: the defendant must have been aware (or at least could have been aware) of the specific circumstances that gave rise to this heightened risk.

Applying this theory to the 1957 case yields a fascinatingly different conclusion. The "particularly high degree of risk" of death from K's assault was predicated on A's hidden vulnerabilities (her heart condition and fatty liver). According to the "heightened risk" theory, for K to be guilty of bodily injury resulting in death, he would have needed to be aware, or at least have been in a position where he should have been aware, of her specific frailties. Since there is no indication that he knew of her unique medical state, this theory would likely lead to his acquittal on the charge of bodily injury resulting in death, holding him liable only for the basic offense of bodily injury or assault.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1957 decision in this case remains a pivotal landmark in Japanese criminal law. It represents the clear and enduring position of the judiciary: for result-aggravated crimes, a causal link between the intentional act and the grave result is sufficient for conviction. The defendant's ability to foresee that result is irrelevant.

Yet, the case's true legacy lies in the enduring and sophisticated debate it continues to fuel. While the courts have maintained a consistent line, legal scholarship has relentlessly challenged this position, seeking to harmonize the law with the fundamental principle of culpability. The competing theories—requiring negligence or focusing on the creation of a "heightened risk"—demonstrate a deep and ongoing intellectual struggle to define the moral and legal boundaries of responsibility for unintended consequences.

This case, born from a moment of domestic violence with an unforeseen tragic end, thus serves as a powerful illustration of one of criminal law's most fundamental questions: are we responsible for the results of our actions, or for the intentions and foresight in our minds? The Japanese legal system's answer, as shown in this 1957 ruling, is complex, contested, and continues to evolve.