The Unfettered Right to Leave: Supreme Court Upholds Union Resignation Freedom Despite Restrictive Agreement

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of February 2, 2007 (Case No. 2004 (Ju) No. 1787: Claim for Confirmation of Non-Existence of Union Membership Status, etc.)

Appellant (Employee): X

Appellees (Union and Company): Y1 Union and Y2 Company

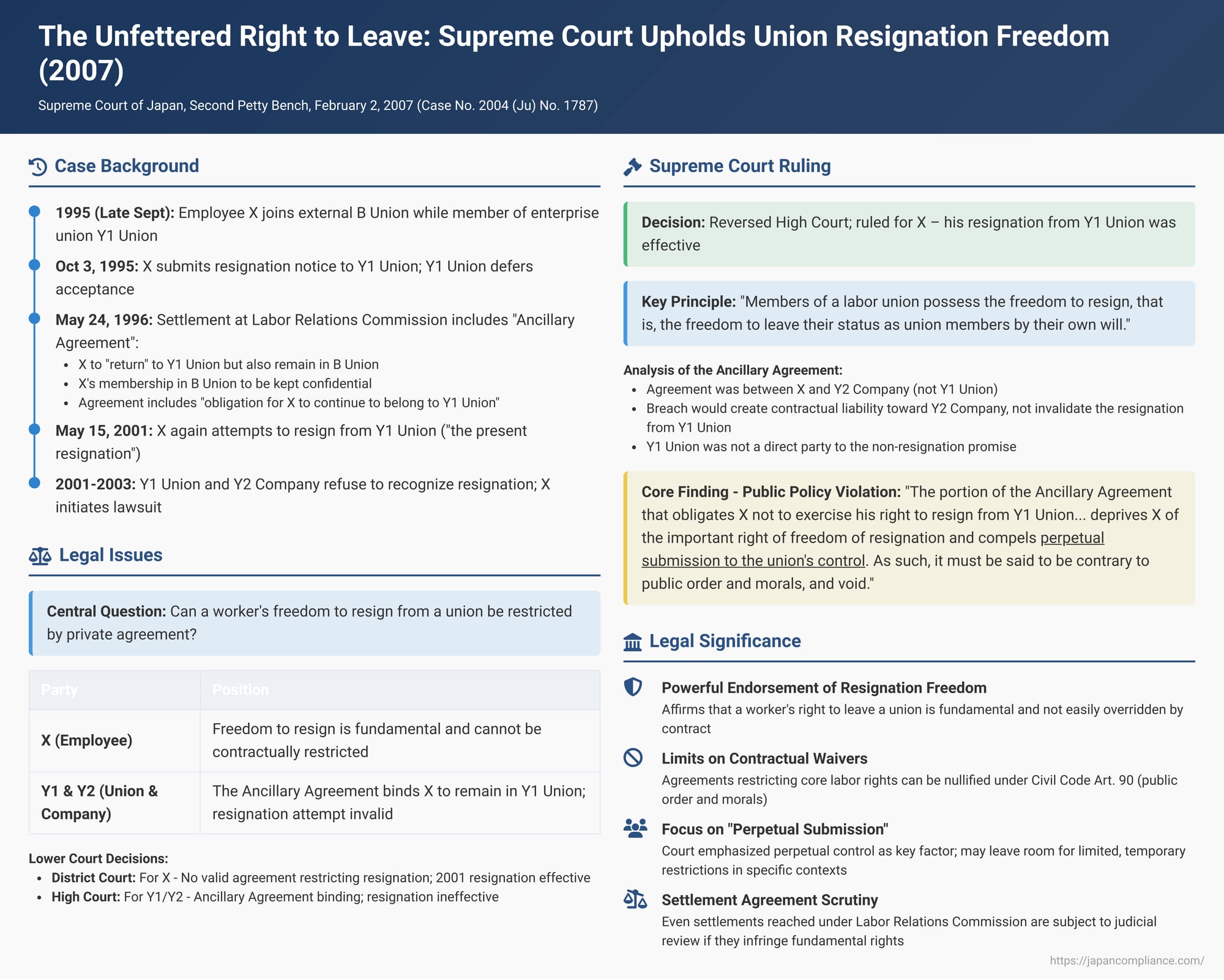

The freedom of an individual worker to join or leave a labor union is a cornerstone of industrial relations. In a significant ruling on February 2, 2007, the Supreme Court of Japan reaffirmed this principle, holding that an employee's freedom to resign from a union cannot be nullified by a private agreement, especially one that compels "perpetual submission" to union control. This case, often referred to as the Toshiba Labor Union Komukai Branch / Toshiba case, delves into the complexities of multi-union membership, settlement agreements brokered by labor relations commissions, and the fundamental nature of the freedom of association.

A Complex History: The Facts Leading to the Dispute

The case involved X, an employee of Y2 Company. Initially, X was a member of Y1 Union, an enterprise-based union primarily composed of Y2 Company's employees at its A factory.

Initial Grievances and Dual Unionism (1995):

Dissatisfied with Y1 Union's approach to certain issues, particularly concerning overtime pay, X decided to seek alternative representation. Around late September 1995, X joined B Union (C Local in the judgment text), an external, broader-based labor union. On October 3, 1995, X formally submitted a resignation notice to Y1 Union. However, Y1 Union deferred acceptance of the resignation and attempted to persuade X to remain a member.

On the same day, X and B Union notified Y2 Company of X's membership in B Union and requested collective bargaining. Y2 Company declined, citing the fact that Y1 Union had not yet accepted X's resignation. This led X and B Union to file an unfair labor practice complaint with the Kanagawa Prefectural Labor Relations Commission on November 7, 1995, against Y2 Company for its refusal to bargain.

The Settlement and a Crucial "Ancillary Agreement" (1996):

On May 24, 1996, a settlement was reached at the Labor Relations Commission involving Y2 Company, X, and B Union. As part of this settlement, Y2 Company agreed to pay B Union ¥2.5 million. Simultaneously, and critically for the subsequent dispute, an "Ancillary Agreement" (本件付随合意 - honken fuzui gōi) was concluded. The Supreme Court judgment outlines the key terms of this Ancillary Agreement, which was made between Y2 Company, X, and B Union:

- X would "return" to Y1 Union but would also retain his membership in B Union.

- X's ongoing membership in B Union was to be kept confidential, particularly from Y1 Union. However, B Union reserved the right to disclose X's membership if Y2 Company treated X unfairly or if other "special circumstances" arose.

The judgment explicitly states that this Ancillary Agreement "also included an obligation for X to continue to belong to Y1 Union." Following this agreement, X withdrew his earlier resignation from Y1 Union.

Renewed Dissatisfaction and Second Resignation Attempt (2000-2001):

Some years later, X (who by then had left B Union and joined another external union, D Union, in 1998) again found himself at odds with Y2 Company over a proposed job transfer in March 2001. X consulted Y1 Union, but Y1 considered the transfer to be acceptable. This response further fueled X's dissatisfaction with Y1 Union.

Consequently, on May 15, 2001, X once again declared his intention to resign from Y1 Union (this is termed "the present resignation" - honken dattai). He also formally requested Y2 Company to cease the check-off (automatic deduction) of Y1 Union membership dues from his wages.

When Y1 Union and Y2 Company effectively refused to recognize his resignation and continued the check-off, X initiated legal proceedings. He sought confirmation from the court that he was no longer a member of Y1 Union, a refund of union dues paid since his resignation (and other union-related funds), and confirmation that Y2 Company was obligated to pay him his full wages without deducting Y1 Union dues.

The Lower Courts' Diverging Paths

The First Instance court (Yokohama District Court, Kawasaki Branch, July 8, 2003) largely found in favor of X. It held that there was no valid agreement obligating X not to resign from Y1 Union and therefore recognized the effectiveness of his 2001 resignation.

However, the High Court (Tokyo High Court, July 15, 2004) overturned this decision. The High Court focused on the 1996 Ancillary Agreement, interpreting it as imposing a binding obligation on X to remain a member of Y1 Union. It concluded that X's 2001 resignation attempt violated this Ancillary Agreement and was therefore ineffective. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Clear Stance: Freedom of Resignation Prevails

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of February 2, 2007, reversed the High Court's decision and ruled in favor of X, affirming his right to resign from Y1 Union.

1. Reaffirmation of the General Freedom of Resignation:

The Court began by unequivocally stating the general principle: "It is generally understood that members of a labor union possess the freedom to resign, that is, the freedom to leave their status as union members by their own will." In support, it referenced two of its prior landmark decisions on union affairs (the K H C case, 1975, and the N K T S case, 1989).

2. Interpreting the Ancillary Agreement:

The Supreme Court then analyzed the 1996 Ancillary Agreement. It found that this agreement essentially constituted a promise made by X to Y2 Company (not Y1 Union) that he would not exercise his right to resign from Y1 Union.

3. Limited Direct Effect of the X-Company Agreement on the Union:

The Court emphasized a crucial distinction regarding the parties to the Ancillary Agreement. Since the agreement was between X and Y2 Company (with B Union also involved in its creation), its direct legal effects were, in principle, confined to these parties. The Court reasoned: "Even if X were to exercise his right to resign from Y1 Union in breach of the Ancillary Agreement, this would, at most, give rise to issues such as liability for breach of contract towards Y2 Company." There was no special basis to find that this agreement between X and Y2 Company would also bind X in his relationship with Y1 Union (which was not a direct contracting party to this promise of non-resignation in the Ancillary Agreement) to the extent of rendering his resignation from Y1 Union itself invalid.

4. The Core Finding: Restriction on Resignation Freedom is Void as Against Public Policy:

This was the centerpiece of the judgment. The Supreme Court declared that the specific part of the Ancillary Agreement that obligated X not to exercise his right to resign from Y1 Union, thereby intending to render any such resignation ineffective, was void as contrary to public order and morals (Article 90 of the Civil Code).

The Court's reasoning was profound:

"A labor union is legally permitted to maintain control over its members, and members are placed in a position where they must comply with this, participate in activities decided by the union, and cannot evade obligations such as paying union dues. However, this is acceptable only on the premise of the freedom to resign from the union."

Therefore, the Court concluded:

"The portion of the Ancillary Agreement that obligates X not to exercise his right to resign from Y1 Union and purports to prevent the resignation itself from taking effect, deprives X of the important right of freedom of resignation and compels perpetual submission to the union's control. As such, it must be said to be contrary to public order and morals, and void."

5. Consequence: X's Resignation Was Effective:

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court held that X's 2001 resignation from Y1 Union could not be deemed ineffective merely because it might have violated the terms of the Ancillary Agreement he had with Y2 Company. The Court also found no other grounds asserted by Y1 Union or Y2 Company that would invalidate X's resignation or permit the continued check-off of union dues. Thus, X's claims were upheld.

Significance and Implications of the Judgment

This Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in Japanese labor law:

- Powerful Endorsement of Freedom of Resignation: The judgment serves as a strong affirmation of an individual worker's fundamental right to leave a labor union. It underscores that this freedom is not easily overridden.

- Limits on Contractual Waivers of Fundamental Labor Rights: It demonstrates that even specific, individual agreements that purport to restrict core labor rights, such as the freedom to resign from a union, can be nullified if they are found to violate public policy. The "public order and morals" clause of the Civil Code acts as a backstop against contractual terms that unduly infringe upon such essential freedoms.

- Importance of Identifying the Parties to an Agreement: The Court's careful distinction between the parties to the Ancillary Agreement (X and Y2 Company) and the party directly affected by the act of resignation (Y1 Union) is crucial. An agreement between a worker and their employer concerning union membership does not automatically dictate the validity of the worker's resignation from the union itself, especially when the union is not a direct party to that specific restrictive covenant.

- "Perpetual Submission" as a Key Element for Invalidity: The Court's emphasis on the agreement compelling "perpetual submission" to union control was a significant factor in finding it contrary to public policy. This phrasing might suggest that agreements imposing very temporary and clearly justified restrictions on resignation (e.g., during a critical phase of a legitimate strike, a point debated in scholarly circles) might not necessarily face the same fate, though this case dealt with an indefinite restriction tied to a complex settlement. The PDF commentary on this case notes that the logic might not deny all temporary restrictions on resignation under different circumstances.

- Underlying Legal Basis of Resignation Freedom: While the Supreme Court did not explicitly ground the freedom of resignation in a specific constitutional article in this judgment, its reference to established precedents and the inherent nature of voluntary associations strongly implies that it views this freedom as a fundamental right. Scholarly discussions on the legal basis of this freedom vary, with some tracing it to the broader right to organize (Constitution Article 28), others to the nature of voluntary associations, and some to a "negative" right to organize.

- Scrutiny of Settlement Agreements: The case also signals that even settlement agreements reached under the auspices of a Labor Relations Commission are not immune from judicial scrutiny if they contain clauses that unduly infringe upon fundamental worker rights.

The PDF commentary does raise some academic points for discussion, such as whether the Supreme Court's specific interpretation of the Ancillary Agreement's intent (to make resignation itself ineffective rather than just creating a contractual obligation towards the company) was necessary, or if the public policy ruling was the most direct route given the Court’s own finding that the X-Y2 agreement did not directly prevent X from resigning from Y1. However, the ultimate outcome and the principles enunciated are clear.

Conclusion

The Toshiba Labor Union Komukai Branch / Toshiba Supreme Court judgment is a vital reaffirmation of an individual worker's autonomy in matters of union association in Japan. It clearly establishes that the freedom to resign from a labor union is a significant right that cannot be easily signed away, particularly through agreements that would lead to "perpetual submission" to a union's control. This decision limits the ability of employers and even complex, multi-party settlement agreements to curtail this fundamental freedom, reinforcing the voluntary nature of union membership. It serves as an important reminder of the balance the law seeks to strike between collective labor rights and individual freedoms.