The Uncalled Capital: When Does a Limited Partner's Unpaid Contribution Extinguish Their Right to a Refund Upon Withdrawal? A Japanese Supreme Court Case

Judgment Date: January 22, 1987

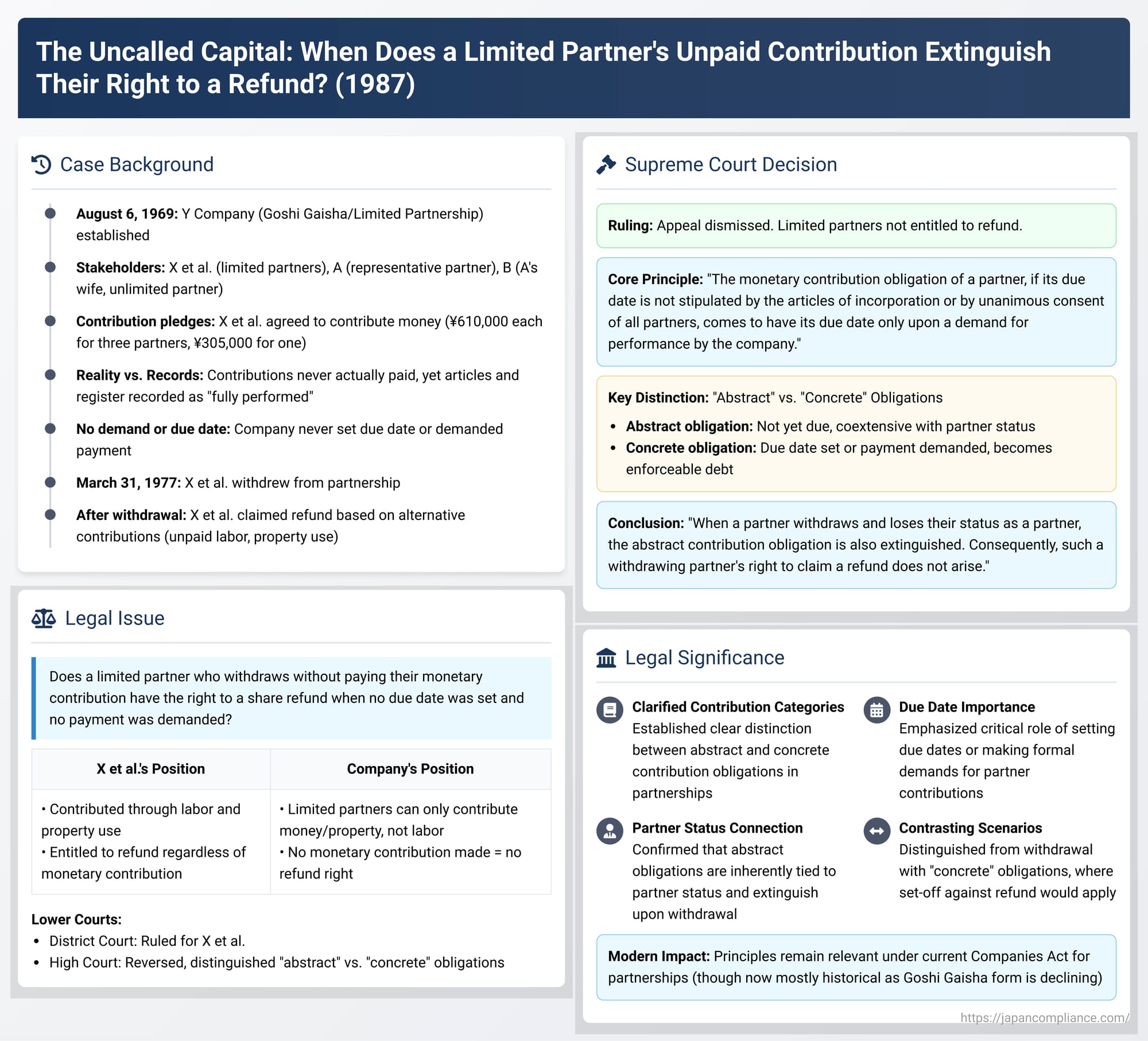

In Japanese company law, particularly concerning traditional partnerships like the Goshi Gaisha (limited partnership), the obligations and rights of partners regarding their capital contributions are fundamental. A critical question arises when a partner, especially a limited partner, withdraws from the partnership: what happens if their agreed-upon monetary contribution was never actually paid, and more importantly, if the company never formally set a due date or demanded its payment? A Supreme Court of Japan decision from January 22, 1987, provides a definitive answer to this scenario, clarifying the relationship between an uncalled capital contribution obligation and a withdrawing partner's right to a refund of their partnership share.

The Factual Matrix: An Unpaid Pledge in a Family Partnership

The case involved Y Company, a Goshi Gaisha established on August 6, 1969. The plaintiffs, X and three others (referred to collectively as X et al.), were limited partners. The unlimited partners were A, who was also Y Company's representative, and A's wife, B.

While the original articles of incorporation outlined certain terms, a subsequent agreement among the partners set the specific contribution amounts and share ratios for each partner. For X et al., the limited partners, the agreed object of their contribution was money. The individual amounts were ¥610,000 each for three of the limited partners and ¥305,000 for the fourth.

Crucially, several facts surrounding these contributions became central to the dispute:

- Non-Payment: X et al. never actually paid these agreed-upon cash amounts to Y Company before their withdrawal.

- Incorrect Records: Despite the non-payment, both Y Company's articles of incorporation and its commercial register were amended or created to state that these monetary contributions by X et al. had been fully performed.

- No Due Date or Demand: At no point before X et al.'s withdrawal on March 31, 1977, was a specific due date for the fulfillment of their monetary contribution obligations set, either in the articles of incorporation or by the unanimous consent of all partners. Furthermore, Y Company never formally demanded that X et al. pay their contributions.

Upon their withdrawal, X et al. initiated a lawsuit against Y Company, claiming a refund of their partnership share. Their primary argument to substantiate their claim to a share value was that they had effectively made contributions through other means – specifically, by performing labor without remuneration for a period after Y Company's store opened, by contributing 20% of their salaries to an alleged slush fund for Y Company, by providing a portion of their leased land free of charge for the construction of Y Company's store, and by offering part of their own building as an employee dormitory.

The Legal Journey: From District Court to the Supreme Court

The Court of First Instance (Naha District Court, Okinawa Branch) initially found in favor of X et al., accepting their claim for a share refund.

However, the Appellate Court (Fukuoka High Court, Naha Branch) reversed this decision, ruling against X et al. The High Court's reasoning was pivotal and laid the groundwork for the Supreme Court's final judgment:

- It first addressed X et al.'s claim of having made labor or property contributions. Under the then-Commercial Code (Article 150), limited partners in a Goshi Gaisha were restricted to contributing only money or other property; labor or credit contributions were not permissible for them (this principle is reflected in the current Companies Act, e.g., Article 576, Paragraph 1, Item 6). Since Y Company's articles specified that X et al.'s contributions were to be in money, their arguments about alternative forms of contribution (labor, use of property not formally valued and contributed as such) were dismissed as a basis for a fulfilled capital contribution.

- The core of the High Court's decision rested on the nature of X et al.'s unfulfilled monetary contribution obligation. It distinguished between an "abstract" contribution obligation and a "concrete" one.

- An obligation is "abstract" when the due date for its performance has not yet been determined by the articles of incorporation, by the unanimous consent of the partners, or by a formal demand from the company. Such an obligation is intrinsically linked to the status of being a partner.

- An obligation becomes "concrete" when its due date has arrived or been set, transforming it into a specific, enforceable monetary debt owed to the company.

- The High Court, citing a 1941 Daishin-in (pre-war Supreme Court) precedent (Daishin-in, May 21, 1941, Minshu Vol. 20, p. 693), concluded that because Y Company had never set a due date for X et al.'s monetary contributions nor demanded their payment, the obligation remained "abstract." When X et al. withdrew from the partnership, this abstract obligation, being inseparable from their status as partners, was extinguished along with that status.

- Consequently, as their monetary contributions were never made (and the obligation to do so was extinguished before becoming a concrete debt), there was no fulfilled contribution value upon which to base a claim for a share refund.

- The High Court contrasted this with a situation where a partner withdraws after the due date for their contribution has passed (i.e., the obligation has become "concrete"). In such a case, the unpaid contribution is treated as an asset of the company, and the withdrawing partner would generally still have a right to a share refund, although the company could set off the unpaid contribution amount against the refund (citing Daishin-in, October 30, 1940, Minshu Vol. 19, p. 2142).

X et al. appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, reiterating their arguments regarding the fulfillment of their contribution obligations (via labor/property) and challenging the High Court's interpretation of their right to a share refund and the status of their contribution obligation.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated January 22, 1987, dismissed the appeal by X et al., thereby upholding the High Court's decision and reasoning.

The Supreme Court's core holding was:

"The monetary contribution obligation of a partner in a limited partnership (Goshi Gaisha), if its due date is not stipulated by the articles of incorporation or by the unanimous consent of all partners, comes to have its due date only upon a demand for performance by the company. Before becoming such a monetary debt (i.e., a concrete obligation), the contribution obligation is to be considered as coextensive with the status of being a partner. Therefore, when a partner withdraws and loses their status as a partner, the contribution obligation is also extinguished. Consequently, such a withdrawing partner's right to claim a refund of their partnership share from the limited partnership does not arise."

The Court explicitly referenced and followed the Daishin-in judgment of May 21, 1941. It confirmed the High Court's findings of fact:

- X et al. were indeed limited partners of Y Company.

- Their object of contribution was, according to Y Company's articles of incorporation, money, with specified amounts.

- Although the articles and the commercial register indicated that these contributions were fully performed, X et al. had not, in reality, paid the corresponding cash amounts before their withdrawal.

- No due date for these monetary contributions had been set by the articles or by unanimous partner consent, and Y Company had not demanded performance of these obligations from X et al. before their withdrawal.

- X et al. withdrew from Y Company on March 31, 1977.

Given these established facts, the Supreme Court concluded that X et al. did not acquire a right to a refund of their partnership share from Y Company, affirming the High Court's judgment as correct.

Unpacking the Legal Concepts and Implications

This Supreme Court decision reinforces several key principles in Japanese partnership law:

- Nature of Contributions for Limited Partners: The case implicitly supports the statutory restriction that limited partners in a Goshi Gaisha can only contribute money or other property that has an assessable value; contributions of labor or credit are reserved for unlimited partners. X et al.'s attempts to claim their labor and informal property provisions as fulfilled capital contributions were not recognized.

- The "Abstract" vs. "Concrete" Contribution Obligation: This distinction is crucial.

- An abstract obligation is a potential duty to contribute, inherent in being a partner, but not yet a matured, specifically enforceable debt. It exists as part of the bundle of rights and duties that constitute partnership status.

- A concrete obligation arises when the performance of the contribution becomes due, either through a pre-set date (in the articles or by unanimous agreement) or, as in this case's scenario, upon a formal demand by the company. Once concrete, it becomes a distinct monetary debt owed by the partner to the company, much like any other receivable.

- Timing of Contribution Fulfillment in Partnerships:

- Unlike Godo Gaisha (a type of company similar to an LLC), where partners must generally fulfill their contribution obligations before the company's incorporation, Gomei Gaisha (general partnerships) and Goshi Gaisha (limited partnerships) allow for the possibility of unfulfilled contributions even after incorporation.

- The Supreme Court's decision confirms that for these latter partnership types, if no specific due date is otherwise established, the company's management (through its ordinary business execution procedures) holds the power to determine the timing and extent of contribution fulfillment by making a demand on the partners. This mechanism is analogous to the principle in Japan's Civil Code (Article 412, Paragraph 3) where a debt with an unspecified due date becomes due upon demand by the creditor.

- Consequences of Withdrawal with an Unfulfilled "Abstract" Obligation:

- The core takeaway is that if a partner's monetary contribution obligation remains "abstract" (i.e., uncalled and not yet due) at the time of their withdrawal, this obligation is extinguished along with their partnership status.

- Because the obligation ceases to exist before it ever becomes a concrete debt, and because the actual cash was never paid into the company, there is no corresponding asset or fulfilled contribution value in the company that could be attributed to that partner's specific monetary pledge for the purpose of a refund.

- This stance is the majority view among legal scholars, although a minority ("positive view") has argued that a refund right might still arise even in such cases, perhaps on the basis that even uncalled commitments have some value or that the right to call capital is an asset. The Supreme Court, however, firmly endorsed the majority "negative view."

- Contrast with Withdrawal with an Unfulfilled "Concrete" Obligation:

- It's important to distinguish this from a scenario where a partner withdraws after their contribution obligation has become "concrete" (i.e., the due date has passed or a demand has been made) but remains unpaid.

- In that situation, the unpaid contribution is considered an enforceable debt owed to the company – a company asset. The withdrawing partner would generally still be entitled to a refund of their share (based on their overall equity, which might include other fulfilled contributions or accumulated profits). However, the company would have the right to set off the amount of the unpaid concrete contribution (plus any interest or damages for non-payment) against the refund payable to the partner.

- Broader Implications for Partnership Finance:

- Profit and Loss Allocation: The definition of "contribution" (fulfilled, abstract unfulfilled, or concrete unfulfilled) also has implications for how profits and losses are allocated among partners. The majority scholarly view is that such allocations are typically based on fulfilled contributions. If a partner has an unfulfilled concrete contribution, consistency might suggest that while they could be allocated profits based on their agreed share, the company could set off the unpaid contribution against their profit distribution. This case, by focusing on the non-existence of a refund for an abstract unfulfilled monetary contribution, indirectly highlights the importance of actual capital infusion for creating refundable value.

- Capital Refund (while remaining a partner): When a partnership refunds a portion of a partner's capital while they remain a partner (e.g., because the company has surplus capital, under Companies Act Article 624), this is understood to be a refund of fulfilled contributions.

- Distribution of Residual Assets in Liquidation: In a liquidation scenario, the basis for distributing residual assets is generally also considered to be fulfilled contributions. However, if the company's assets are insufficient to cover its debts, the liquidator can call upon partners to fulfill any outstanding (including previously abstract) contribution obligations to the extent necessary (Companies Act Article 663).

Conclusion

The 1987 Supreme Court decision provides a clear and stark message for partners in Japanese Goshi Gaisha (and by extension, Gomei Gaisha regarding this principle): a monetary contribution that is neither paid nor formally called by the company before a partner's withdrawal essentially vanishes as an obligation and provides no basis for a share refund relating to that specific unfulfilled monetary pledge. The obligation, in its "abstract" state, is intrinsically tied to the partner's status and ceases to exist when that status is lost. This underscores the importance for partnerships to clearly define the due dates for capital contributions or to make formal demands for payment if they intend these obligations to become concrete, enforceable debts that survive a partner's withdrawal and factor into the calculation of any share refund. For partners, it highlights that merely being listed in records as having contributed, without actual payment and a formal call for that payment, does not create a refundable interest for that specific unpaid amount upon exit.