The Trial of 'Yojōhan': Japan's Landmark Case on Literature and Obscenity Law

The line between protected artistic expression and illegal obscenity has long been one of the most contentious areas of law in free societies. Where does a community draw the boundary between literature that explores human sexuality and pornography that merely appeals to prurient interest? This question was put directly to the test in Japan in a famous and highly controversial case involving the prosecution of a magazine for publishing a classic, but sexually explicit, work of literature.

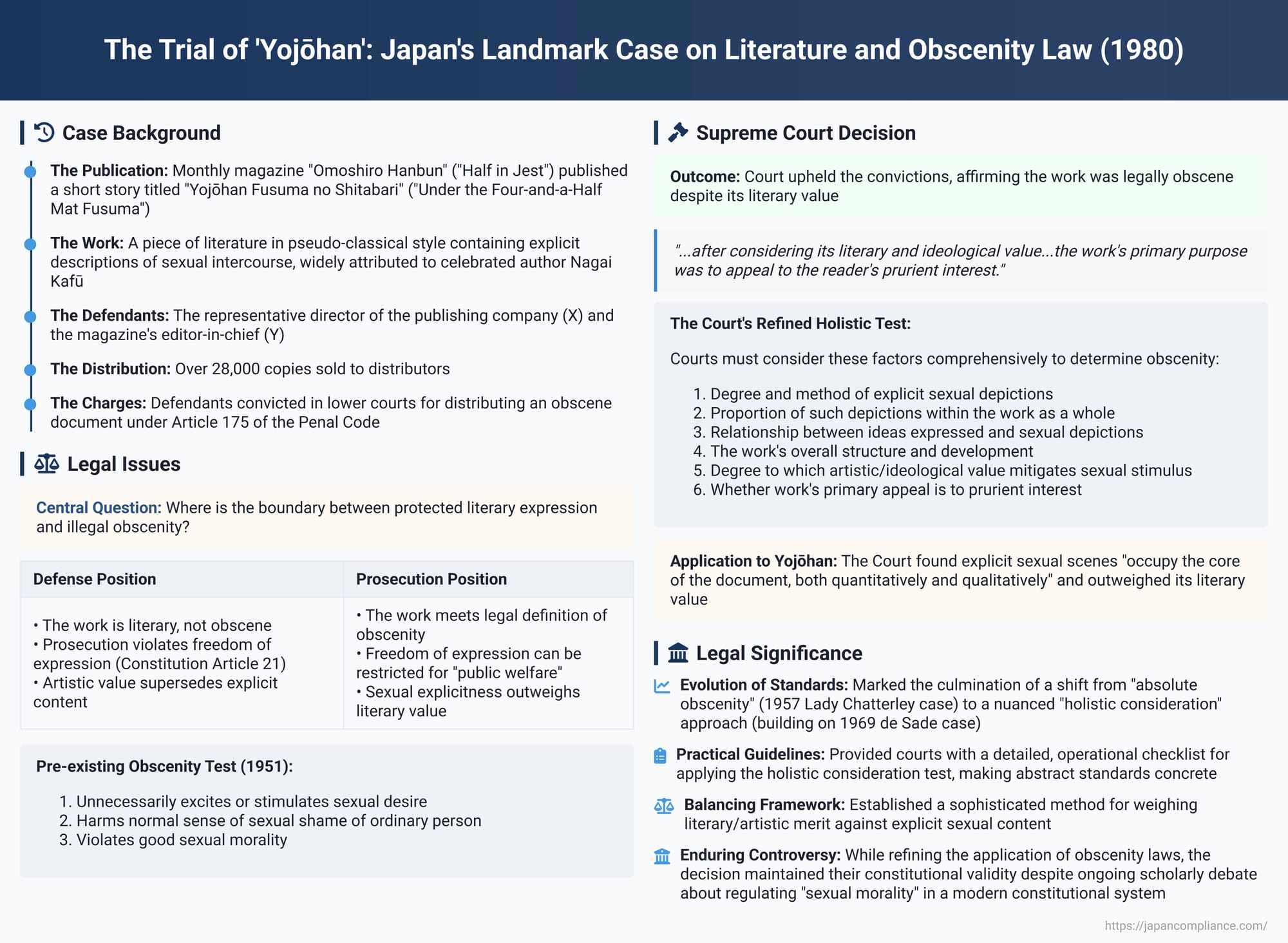

The case, which culminated in a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 28, 1980, forced the judiciary to refine its definition of "obscenity" and articulate its most detailed framework for balancing the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression against the state's interest in maintaining public morals.

The Facts: Publishing a Controversial Classic

The case revolved around a monthly magazine, Omoshiro Hanbun ("Half in Jest"), and its decision to publish a short story titled Yojōhan Fusuma no Shitabari ("Under the Four-and-a-Half Mat Fusuma").

- The Work: The story is a piece of literature written in a pseudo-classical style that contains explicit and detailed descriptions of sexual intercourse, including the participants' physical actions, dialogue, sounds, and sensations. It is widely considered by literary scholars to have been written by Nagai Kafū, one of modern Japan's most celebrated authors.

- The Defendants: The defendants were X, the representative director of the company that published the magazine, and Y, the magazine's editor-in-chief at the time.

- The Publication: After deciding to include the story in their July issue, they published it and sold over 28,000 copies to distributors.

The defendants were subsequently charged and convicted in the lower courts for distributing an obscene document in violation of Article 175 of the Penal Code. They appealed, arguing that the work was a piece of literature, not obscenity, and that the prosecution infringed upon their freedom of expression, guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Legal Battle: Freedom of Expression vs. Public Morality

The case brought into sharp focus the long-standing legal battle over Japan's obscenity laws.

- The Protected Interest: Precedent from Japan's Supreme Court has established that the purpose of obscenity laws is to protect a minimum level of public sexual morality and order. This has been described as safeguarding the "non-public nature of sexual acts" or maintaining "order concerning sexual life and sound customs."

- Constitutionality: The Supreme Court has consistently held that Article 175 is constitutional. It reasons that freedom of expression is not absolute and can be restricted for the "public welfare," a concept that includes the protection of sexual morality.

- The Classic Definition of Obscenity: A 1951 Supreme Court decision established a foundational three-prong test for obscenity. A work is obscene if it:

- Unnecessarily excites or stimulates sexual desire.

- Harms the normal sense of sexual shame of an ordinary person.

- Violates good sexual morality.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Test for Obscenity

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, but in doing so, it synthesized and refined decades of case law into its most comprehensive test for determining obscenity in a written work. The Court affirmed that the ultimate question is whether a work meets the classic three-prong definition, judged according to the "sound social common sense of the era." To reach this conclusion, however, it laid out a multi-factor "holistic consideration" that courts must undertake.

The factors to be "comprehensively considered" are:

- The degree and method of the document's explicit and detailed sexual depictions.

- The proportion of such depictions within the work as a whole.

- The relationship between the ideas expressed in the work and the sexual depictions.

- The work's overall structure and development.

- The degree to which any artistic or ideological value mitigates or "sublimates" the sexual stimulus.

- Whether, after considering all of the above, the work's primary appeal is to the reader's prurient interest.

Applying this detailed test to Yojōhan Fusuma no Shitabari, the Supreme Court concluded that it was, in fact, legally obscene. It found that the "parts depicting scenes of sexual intercourse between a man and a woman with sensational brushwork in an explicit, detailed, and concrete manner occupy the core of the document, both quantitatively and qualitatively." Even after taking into account its "literary and ideological value," the Court determined that the work's primary purpose was to "appeal to the reader's prurient interest."

Analysis: The Evolution of Japan's Obscenity Standard

This 1980 decision represents the culmination of a long evolution in Japanese judicial thinking on obscenity.

- From "Absolute Obscenity" to "Holistic Consideration": A famous 1957 case concerning the translation of Lady Chatterley's Lover had established a theory of "absolute obscenity," which held that artistic value and obscenity were separate concepts; a work could be both artistic and obscene. This approach also allowed for a part of a work to render the entire piece obscene. However, a major 1969 case involving the works of the Marquis de Sade shifted this standard. That ruling introduced the concept of "holistic consideration," acknowledging that a work's artistic or ideological merit could diminish or mitigate the sexual stimulus of explicit passages.

- The Yojōhan Refinement: The 1980 Yojōhan decision is best understood as providing a detailed, practical checklist for how to conduct the "holistic consideration" mandated by the de Sade ruling. It operationalized the standard, giving lower courts a clear set of factors to weigh. The High Court's attempt to create a two-part test (requiring both explicit depiction and a sensual method) was also noted by legal commentators as a valuable step toward clarifying and objectifying the standard.

Despite this judicial refinement, the very foundation of obscenity law remains a subject of intense critique among scholars. Many question whether the criminal enforcement of a particular "sexual morality" is compatible with modern constitutional values of individual autonomy and pluralism. Alternative justifications for regulation—such as preventing sex crimes, protecting minors, or safeguarding the "right not to see"—would likely lead to different regulatory schemes, such as time, place, and manner restrictions, rather than the broad, content-based ban found in Article 175.

Conclusion

The 1980 Supreme Court decision in the Yojōhan case did not fundamentally alter the constitutionality of Japan's obscenity law. Instead, it provided the most sophisticated and detailed judicial framework to date for applying that law to complex works that blend high artistic value with explicit sexual content. By mandating a multi-factor, holistic analysis, the Court attempted to create a principled way to distinguish between protected art and illegal obscenity. The decision stands as a testament to the enduring legal challenge of balancing freedom of expression with the protection of public morals, a balance that must, in the Court's own words, ultimately be judged against the evolving "sound social common sense of the era."