The Timing of "Just Compensation": A 1949 Japanese Supreme Court Decision on Wartime Requisitions

Date of Judgment: July 13, 1949

Case: Food Management Act Violation Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Introduction: Scarcity, Control, and Constitutional Rights in Post-War Japan

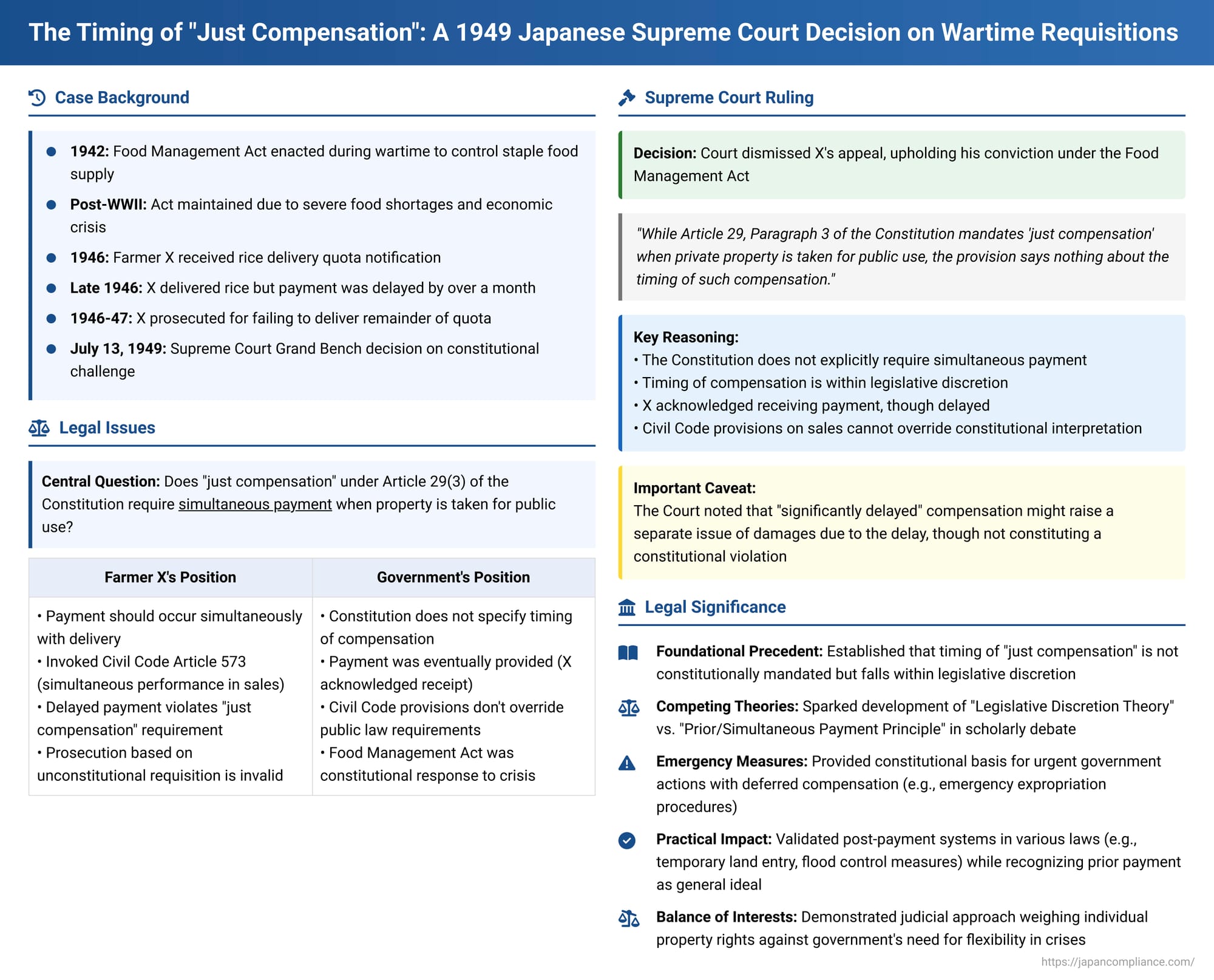

The immediate post-World War II period in Japan was marked by severe food shortages and a crippled economy. To manage the crisis and ensure a stable food supply, the government maintained and enforced stringent controls, many of which originated during the wartime era. One of the most critical pieces of legislation in this regard was the Food Management Act, which mandated that agricultural producers, particularly rice farmers, sell specified quotas of their produce to the government at official prices. This system of compulsory delivery, while deemed necessary for national survival, inevitably led to friction and legal challenges, particularly when measured against the newly enacted Constitution of Japan with its guarantees of property rights and "just compensation."

A foundational case exploring the contours of these rights, specifically the timing of compensation, reached the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on July 13, 1949. This case, arising from a criminal prosecution under the Food Management Act, forced the Court to interpret what "just compensation" under Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution means in terms of when payment must be made for property taken for public use.

The Food Management Act and Farmer X's Constitutional Challenge

The old Food Management Act (旧食糧管理法, Act No. 40 of 1942) was a wartime measure designed to control the supply, distribution, and price of staple foods, most notably rice. It remained a cornerstone of Japan's food policy well into the post-war era, only being abolished in 1995. Under this Act, rice producers were subject to a "delivery obligation" (供出義務), requiring them to sell a government-allocated quantity of their rice to the State. Failure to meet this quota was a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment.

The appellant in the 1949 Supreme Court case, a farmer whom we will refer to as X, was notified of his rice quota for the 1946 harvest year. He subsequently failed to deliver a portion of this allocated amount by the specified deadline. Consequently, X was prosecuted and received a sentence of eight months' imprisonment for violating the Food Management Act.

After his conviction was upheld by the Nagoya High Court, X filed a "re-appeal" (再上告) to the Supreme Court. This special avenue of appeal was available under transitional legislation that allowed for direct appeals to the highest court on grounds of alleged constitutional violations. X's central constitutional claim revolved around the timing of the payment he received for the rice he did deliver. He argued that the payment from the government was delayed by more than a month after the delivery. Invoking principles from the Civil Code—specifically Article 573 (which implies simultaneous performance of delivery and payment in a sale) and Article 533 (which grants the right to demand simultaneous performance)—X contended that payment for the requisitioned rice should have been made at the same time as its surrender. The delay, he argued, meant that his property was effectively expropriated without the "just compensation" guaranteed by Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution, rendering the government's demand for delivery under such conditions unconstitutional and his prosecution unjust.

The Supreme Court's Stance: Timing Not Explicitly Guaranteed by the Constitution

The Supreme Court, in a Grand Bench decision, dismissed X's re-appeal, thereby upholding his conviction. The Court's reasoning meticulously addressed the constitutional question of compensation timing.

1. Constitutional Silence on Timing:

The core of the Court's judgment was that while Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution unequivocally mandates "just compensation" when private property is taken for public use, the provision itself "says nothing about the timing of such compensation". Therefore, the Court concluded, the Constitution does not guarantee that compensation must be paid simultaneously with the surrender of the property. The right to an exchange-like, concurrent performance was not considered a constitutionally protected element of "just compensation".

2. Acknowledgment of Potential Issues with Significant Delays:

However, the Court did not give the government carte blanche regarding payment delays. It acknowledged that if compensation were "significantly delayed" after the property was taken, this "might raise an issue of compensating for damages due to the delay". This important caveat suggested that while simultaneous payment wasn't a strict constitutional requirement, unreasonable or prejudicial delays could potentially lead to a separate claim for losses incurred due to that tardiness. Nevertheless, this did not elevate simultaneous performance to a constitutional right.

3. Application to Farmer X's Case:

Applying these principles, the Court found X's constitutional argument unpersuasive. It noted that it was a "publicly known fact" that the government provided just compensation for rice delivered under the Food Management Act, and significantly, X himself acknowledged having received such payment. The issue was simply that the payment occurred after the delivery of the rice. Given the Court's interpretation that the Constitution does not mandate simultaneous payment, this post-delivery payment was not deemed unconstitutional. Thus, X's assertion that the government's failure to pay simultaneously violated Article 29(3) was found to be without merit.

The Court also stated that there was no necessity for the lower court's judgment to specifically detail the facts of compensation when adjudicating a violation of the Food Management Act itself. Furthermore, X's arguments concerning violations of Civil Code provisions were dismissed as not constituting a constitutional issue, and therefore, not forming a proper basis for the re-appeal. (A minority of justices dissented, but on the procedural ground that the constitutional argument had not been properly raised in the lower appeal court, rather than on the substantive interpretation of compensation timing).

Unpacking "Just Compensation": The Principle of Prior/Simultaneous Payment in Theory and Practice

The 1949 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling precisely because it directly addressed the temporal aspect of "just compensation". While the outcome was unfavorable to X, the case spurred considerable legal discussion on the ideal versus the constitutionally mandated timing of such payments.

The Ideal: Prior or Simultaneous Compensation

In many legal systems and in standard practice, particularly concerning land expropriation (a classic example of Art. 29(3) in action), there is a strong principle favoring prior or simultaneous compensation. In Japan, the Land Expropriation Act, for instance, explicitly requires that compensation be paid before or at the time of the government's acquisition of rights to the land; failure to do so can render the expropriation ineffective. This principle is partly practical, ensuring the property owner has funds before dispossession and allowing time for administrative processes like payment into a public depository if the owner refuses to accept the sum offered. Even general governmental accounting laws in Japan, which typically favor post-payment for services, make exceptions for advance payments where necessary, with land compensation being a recognized instance. These provisions suggest an underlying acceptance of the prior/simultaneous payment ideal in the context of loss compensation.

The Constitutional Reality: Legislative Discretion

Despite this ideal, the 1949 Supreme Court found that the Constitution itself does not elevate this principle to an absolute right. The Court's position effectively placed the precise timing of compensation within the realm of legislative discretion, meaning that laws could, without violating the Constitution, allow for payment after the taking of property, provided the compensation itself was "just".

This ruling gave rise to, or at least solidified, a dominant legal theory which posits that since the Constitution is silent on the specific timing, it is a matter for legislative policy to determine whether compensation should be prior, simultaneous, or posterior. This view is based on the Constitution's lack of explicit language on timing and the practical need to consider different scenarios, including those where compensation amounts can only be accurately determined after the fact or where commercial customs might vary.

An alternative perspective argues that the principle of prior or simultaneous compensation is implicitly contained within the concept of "just compensation". Proponents of this view draw on historical legislative examples from other countries and the existence of Japanese laws that do mandate prior/simultaneous payment, suggesting these reflect a deeper constitutional norm. However, even this theory generally concedes that post-payment can be constitutionally permissible if there is a reasonable justification for it.

While these two theories are theoretically distinct, their practical implications often converge. The first, while granting legislative discretion, would likely acknowledge prior/simultaneous payment as an ideal or good legislative policy in many cases. The second, while starting from prior/simultaneous payment as a default, allows for exceptions under reasonable circumstances.

Justified Exceptions to Prior/Simultaneous Payment

Legal scholarship has identified several situations where post-payment of compensation might be reasonably justified:

- When the extent of the loss cannot be clearly determined before the state action, such as in cases of temporary land entry for surveys or preliminary investigations.

- In emergency situations requiring immediate government action, such as flood control measures or responses to disasters affecting roads.

- When the property rights being affected are diverse or complex, making advance calculation of compensation unfeasible, such as certain losses arising from the designation of city planning zones.

The specific context of the Food Management Act during a period of national food crisis could arguably be seen as one such exceptional circumstance where the overriding public need for food supply might justify a payment system that was not strictly simultaneous, provided the compensation was otherwise "just" and eventually paid.

It's also noted in legal analysis that consideration should be given to the behavior of the recipient; the principle of prior payment should not be abused by parties who have no intention of fulfilling their own obligations. The Supreme Court’s denial of the direct applicability of Civil Code sales provisions to the constitutional interpretation of compensation timing has been largely accepted, as constitutional compensation for public taking is considered a different legal dimension from private contractual sales.

The Broader Implications: Emergency Measures and Legislative Flexibility

The 1949 Supreme Court decision has had a lasting impact, particularly in bolstering the constitutionality of legislative schemes that allow for urgent expropriation or use of property with payment mechanisms that are not strictly prior or simultaneous. The ruling's core tenet—that prior or simultaneous payment is not an absolute constitutional command and that post-payment is permissible under legislative policy—has been cited in subsequent jurisprudence.

For example, the Act on Special Measures for Acquisition of Public Lands (enacted in 1961) established procedures for emergency rulings/decisions by expropriation committees. In specific public projects, if delays in the standard expropriation process threaten project implementation, these emergency procedures allow for acquisition and eviction orders even if full deliberations on the final compensation amount have not concluded. Instead, a provisional sum is paid in advance, with the final amount determined later. The 1949 judgment has been used as a basis to affirm the constitutionality of such systems, including in cases related to land for U.S. military bases in Japan.

This demonstrates how the 1949 ruling, born out of the exigencies of post-war food control, provided a constitutional foundation for legislative flexibility in structuring compensation payments, especially in contexts deemed urgent or critical for public purposes. It underscores a judicial approach that balances the protection of individual property rights with the state's need to act effectively for the public good, sometimes under pressing circumstances.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1949 decision in the Food Management Act Violation Case is a seminal judgment in Japanese constitutional law. It clarified that while "just compensation" is a fundamental right guaranteed by Article 29, Paragraph 3, the precise timing of this compensation—specifically, a demand for payment simultaneous with the taking of property—is not explicitly enshrined in the Constitution itself. Instead, the Court determined that this aspect falls within the scope of legislative discretion.

This ruling does not imply that the government can delay payments indefinitely or arbitrarily. The Court's own words hinted at the possibility of claiming damages for unreasonable delays, suggesting that legislative discretion is not entirely unfettered. Nevertheless, the decision provided a degree of latitude to the government, particularly important during a period of national crisis and reconstruction. It reflected a pragmatic balancing act, acknowledging the severe practical challenges of the time while affirming the underlying principle of just compensation. The case continues to be a key reference for understanding the constitutional framework surrounding state compensation in Japan, especially concerning schemes that involve deferred or provisional payment mechanisms in the pursuit of public objectives.