The Thin Line Between Work Order and Punishment: Japan's JNR Kagoshima Case Revisited

In any employment relationship, employers retain the authority to direct their employees' work through what are known in Japan as "business/work orders" (業務命令 - gyōmu meirei). This authority is essential for operational efficiency and achieving business objectives. However, this power is not absolute and is subject to legal limitations, particularly when an order appears to deviate from an employee's normal duties or seems intended as a punitive measure rather than a legitimate operational requirement. The Supreme Court of Japan's decision in the JNR Kagoshima Motor Vehicle Operations Office case, delivered on June 11, 1993, is a significant, albeit highly debated, ruling that explored these boundaries in a context of intense labor-management conflict.

The JNR Kagoshima Dispute: Badge of Defiance, Ashes of Contention

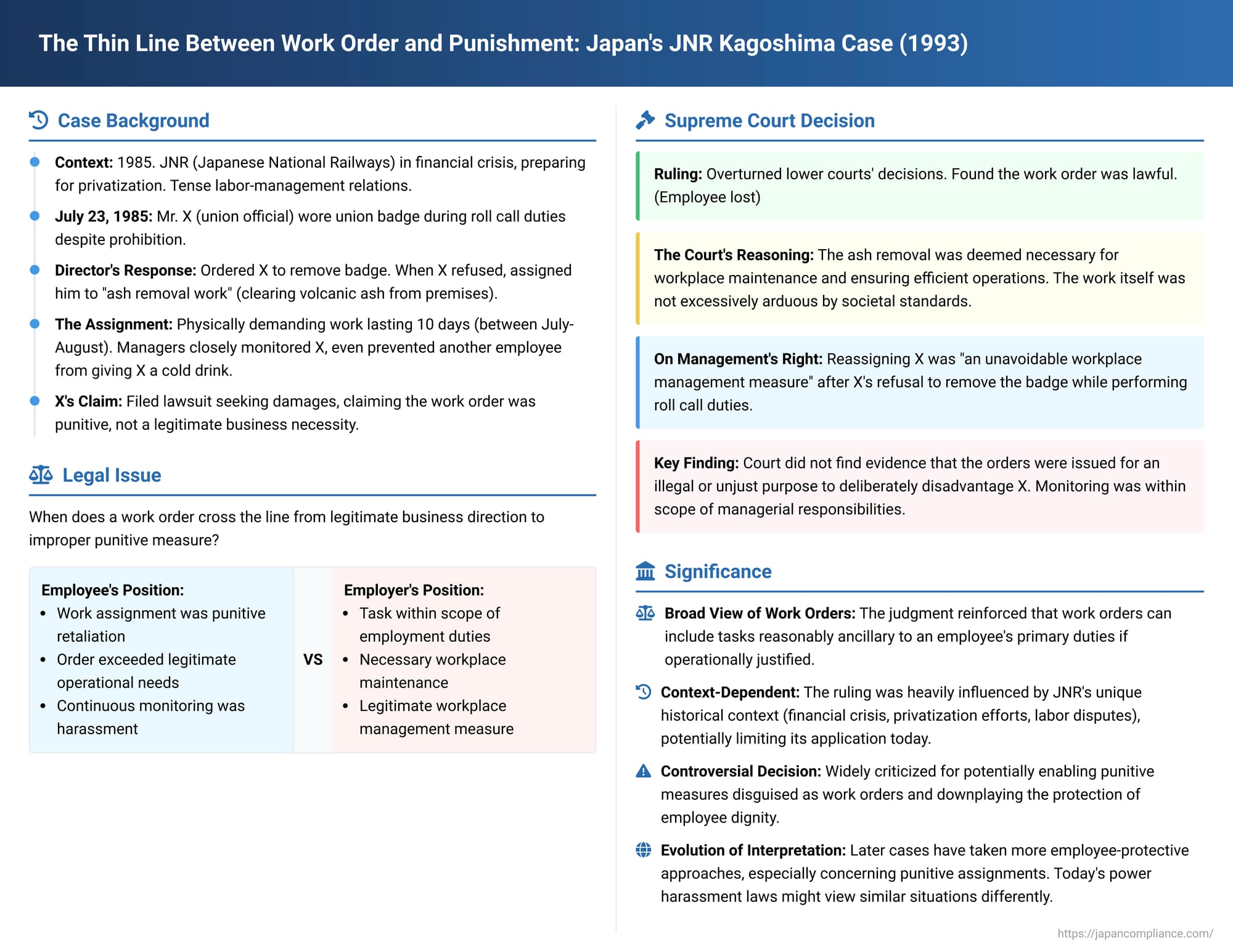

The case arose in 1985, a period when Japanese National Railways (JNR) was facing a severe financial crisis and was in the throes of a contentious reconstruction effort. Management was focused on improving operational efficiency and establishing stricter workplace discipline, an area where JNR had faced public criticism. The plaintiff, Mr. X, was a transport management clerk at JNR's Kagoshima Motor Vehicle Operations Office ("the K office") and also a senior official in the National Railway Workers' Union (Kokuro or "the K Union"). The K Union was strongly opposed to JNR's rationalization policies, leading to a state of constant confrontation between labor and management. In this tense atmosphere, the K office management had implemented a policy prohibiting employees from wearing items like union badges during working hours, aiming to address what it considered disorderly attire and maintain discipline.

On July 23, 1985, Mr. X attempted to conduct his roll call duties while wearing his K Union membership badge. The office director, Y1, instructed X to remove the badge. X refused to comply. In response, Y1 removed X from his standard duties and issued a work order for him to engage in "ash removal work" (降灰除去作業 - kōhai jogyo sagyō). This task involved clearing volcanic ash from the nearby Sakurajima volcano that had accumulated on the extensive K office premises, an area exceeding 1200 square meters.

The ash removal work was described as physically demanding and unpleasant. It required sweeping the ash and then using shovels to put it into vinyl bags, with a risk of inhaling ash and suffering inflammation. Prior to this incident, such work had either been outsourced to external contractors or occasionally performed by groups of employees voluntarily at suitable times. During X's assignment to this task, Y1 and another manager, Y2 (an assistant stationmaster/deputy director), continuously monitored his work. In one instance, Y1 stopped another employee from giving X a cold drink while he was working. X was ordered to perform this ash removal work, from approximately 8:30 AM to 5:00 PM with a one-hour break, for a total of 10 days between July 23 and August 30, 1985.

Mr. X sued Y1 and Y2, seeking 500,000 yen in damages for mental distress. He argued that the work order was unjust, went beyond legitimate operational requirements, and constituted a punitive retaliatory measure for his refusal to remove the union badge.

The Kagoshima District Court and the Fukuoka High Court (Miyazaki Branch) both ruled in favor of X. They found that while ash removal might be considered an ancillary duty, ordering X to perform it under these circumstances lacked genuine necessity and was clearly punitive. The courts acknowledged that X's refusal to remove the badge was a minor breach of his duty of devotion to work (職務専念義務 - shokumu sennen gimu), but held that disciplinary matters should be addressed through formal channels, not by assigning arduous and distressing tasks. They concluded that the work order constituted an abuse of the employer's right to issue such orders and was therefore illegal. Y1 and Y2 appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 1993 Reversal

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the lower courts' decisions and dismissed X's claim, finding the work orders lawful.

The Court reasoned as follows:

- Nature and Necessity of the Ash Removal Work: The task was deemed necessary for maintaining the workplace environment at the K office and for ensuring the smooth and efficient conduct of operations. The Court also found that the work content and method were not, by societal standards, excessively arduous or beyond what could be reasonably expected. It noted that even the lower courts acknowledged the work fell within the scope of X's contractual employment duties.

- Justification for the Order to X: The Supreme Court emphasized that the orders were issued because X attempted to perform his regular duties (roll call) while actively violating a valid instruction from his superior (Y1's order to remove the union badge). The decision to remove X from his standard duties and reassign him was based on instructions Y1 had received from a higher JNR authority, the Regional Department. Assigning X to outdoor ash removal work was characterized by the Court as a "workplace management measure that was unavoidable" (職場管理上やむを得ない措置) and considered less disruptive to overall workplace discipline under the circumstances.

- Absence of Improper Motive: The Court stated that it did not find the orders to have been issued for an illegal or unjust purpose of deliberately or unnecessarily disadvantaging X.

- Supervision Methods: The actions of Y1 and Y2 in monitoring X's work and preventing another on-duty employee from giving X a beverage were also considered within the scope of their managerial responsibilities and not specifically illegal or improper.

Based on this assessment, the Supreme Court concluded that it was "extremely difficult" to deem the work orders illegal.

Analyzing the Scope and Limits of Work Orders

This case touches upon fundamental aspects of Japanese employment law concerning an employer's authority to direct work.

Contractual Basis of Work Orders:

It is a settled principle that an employer's authority to issue work orders stems from the labor contract, wherein the employee agrees to provide labor under the employer's direction. Consequently, any work order must generally fall within the scope of duties defined or implied by that contract. This includes not only the employee's primary tasks but also reasonably ancillary or incidental duties necessary for the smooth functioning of the business.

The "Ancillary Duties" Debate:

The JNR Kagoshima Supreme Court decision, while acknowledging the contractual basis, appeared to take a broad view of what might constitute ancillary duties. It justified the ash removal order by its necessity for workplace maintenance and operational efficiency, and for upholding discipline, rather than by a detailed analysis of X's specific contractual job description. This approach has drawn criticism from some legal commentators who argue that it could potentially allow employers to assign almost any task to an employee under the guise of operational necessity or maintaining discipline, thereby excessively expanding employer power. The dominant academic view tends to favor a more restrictive interpretation, suggesting that legitimately assignable ancillary duties should be those closely related to the employee's primary job function.

Abuse of Rights Doctrine:

Even if a work order is technically within the scope of an employee's contractual obligations, it can still be deemed illegal if it constitutes an abuse of the employer's rights. This is a general principle in Japanese law, now explicitly stated for labor contracts in Article 3, Paragraph 5 of the Labor Contract Act. An abuse of rights can occur if an order is issued for an improper purpose (e.g., harassment or retaliation), is excessively harsh or disproportionate to any legitimate aim, or otherwise violates principles of good faith and fair dealing.

The JNR Kagoshima "Abuse" Finding (or lack thereof):

The lower courts had found the ash removal order to be an abuse of Y1's authority, emphasizing its punitive nature and the physical and mental distress caused to X. The Supreme Court's reversal of this finding has been a focal point of criticism. Commentators have argued that the Supreme Court's decision downplayed the clearly punitive aspects of the assignment, the demeaning nature of the continuous surveillance, and the overall impact on X's dignity and personality rights. The argument is that using an otherwise legitimate task as a means of punishment, especially without recourse to formal disciplinary procedures, can itself render a work order abusive.

Context and Subsequent Developments

It is widely acknowledged that the JNR Kagoshima decision was heavily influenced by its unique historical context. The period was marked by:

- JNR's Crisis and Privatization Efforts: JNR was on the brink of privatization, facing immense financial pressure and a political mandate to reform, which included cracking down on perceived indiscipline and challenging union practices.

- Intense Labor-Management Conflict: The relationship between JNR management and powerful unions like Kokuro was exceptionally adversarial.

- Status of JNR Employees: As employees of a public corporation, JNR staff were subject to a heightened duty of devotion to their work, akin to civil servants, which might have led courts to grant management wider latitude in enforcing discipline.

Given these factors, legal commentators suggest that if a similar situation arose in a typical private sector company today, without the backdrop of JNR's specific circumstances, there would be a greater likelihood of such a work order being deemed an abuse of rights.

Subsequent case law seems to support a more nuanced and employee-protective approach in certain situations:

- In the JR West Suita Plant case (Osaka High Court, 2003), an order for an employee to perform a monotonous railway crossing monitoring task in harsh summer conditions was found to be an illegal abuse of rights, with the court distinguishing it from the JNR Kagoshima facts.

- In the JR East Honjo Maintenance Depot case (Supreme Court, 1996), an order for an employee who committed a minor infraction to repeatedly copy the work rules, ostensibly as "education and training," was deemed punitive, an abuse of discretion, and an infringement of personality rights because its true purpose was to make an example of the employee and inflict mental distress. This case suggests that the proportionality of the "task" to the alleged misconduct and the genuineness of its operational purpose are critical considerations.

Relevance to Modern Power Harassment Laws:

It's also important to note that workplace conduct like that described in the JNR Kagoshima case could today be scrutinized under contemporary frameworks for preventing power harassment. If a superior's actions are found to take advantage of their dominant position, to go beyond the necessary and reasonable scope of business, and to harm the employee's working environment, they could constitute illegal power harassment. The assignment of demeaning or punitive tasks unrelated to an employee's core responsibilities fits this pattern.

Conclusion

The JNR Kagoshima Motor Vehicle Operations Office case remains a significant, if controversial, decision in Japanese labor law. The Supreme Court found the specific work order—assigning an employee to arduous ash removal duties following an act of defiance—to be a permissible, albeit "unavoidable," workplace management measure under the extreme and highly confrontational circumstances prevailing at JNR at the time.

However, the case also serves as a crucial touchstone for discussing the general principles that work orders must be contractually grounded and must not constitute an abuse of an employer's rights. While the Supreme Court in this instance gave considerable leeway to managerial discretion in a volatile public sector context, the extensive criticism and the trajectory of subsequent case law, particularly concerning punitive assignments and the protection of employee dignity, suggest that the legal landscape continues to evolve. In contemporary private-sector employment, the imposition of tasks primarily for punitive or harassing purposes, rather than genuine operational need, would likely face much stricter judicial scrutiny, including under the lens of power harassment regulations.