The Thin Line Between Private and Common: A Deep Dive into a Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Condominium Spaces

Date of Judgment: February 12, 1993

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, 1990 (O) No. 1369 – Claim for Cancellation of Ownership Preservation Registration, etc.

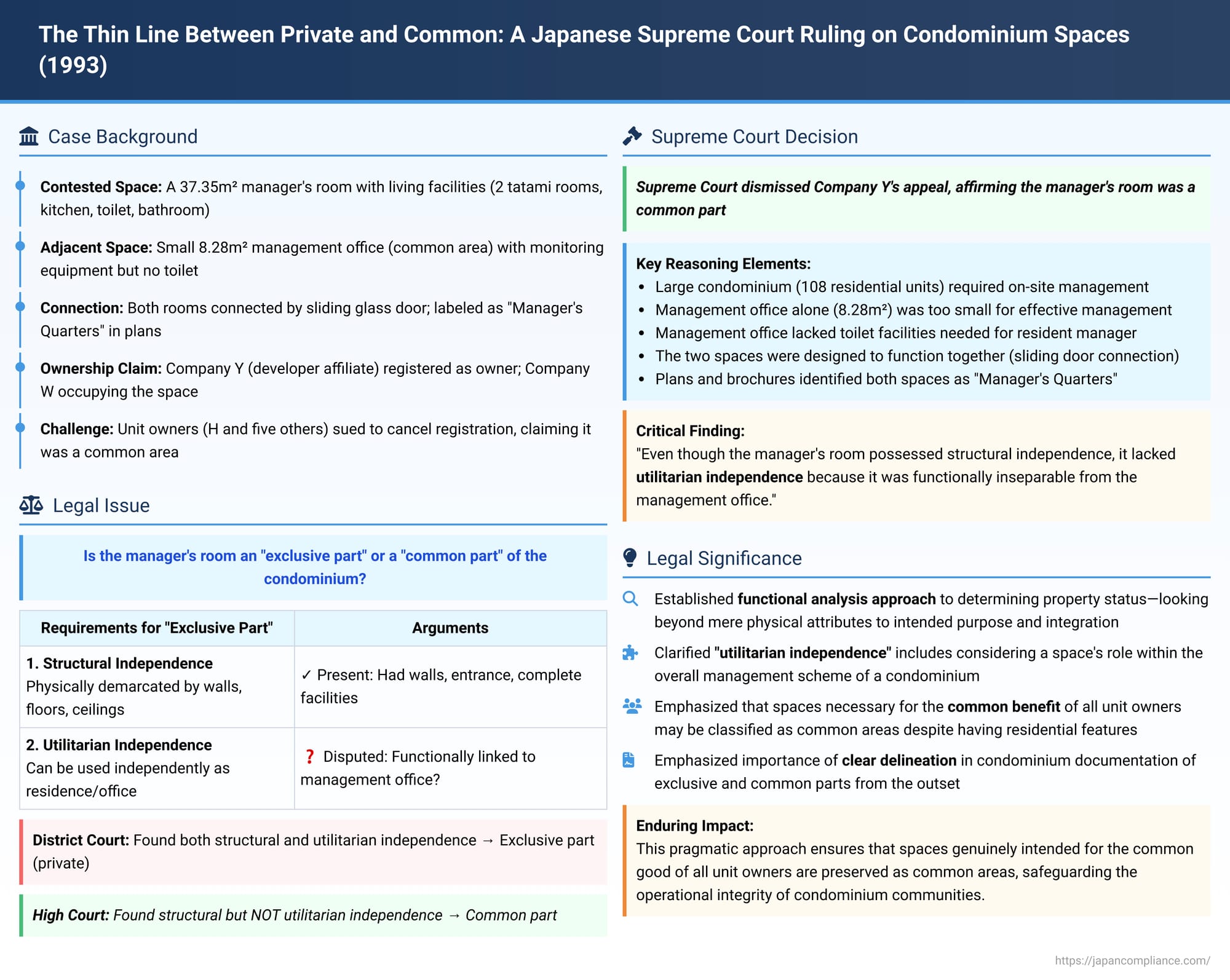

In the realm of co-owned properties like condominiums, the distinction between what constitutes an individual owner’s private space and what is designated as a common area for all residents is of paramount importance. This delineation affects ownership rights, responsibilities for maintenance, and the overall governance of the shared living environment. A pivotal 1993 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan delved deep into this issue, particularly concerning a manager's room within a condominium complex. The case offers valuable insights into the legal criteria used to classify parts of a building, emphasizing not just physical structure but also functional purpose and intended use.

The Setting: A Condominium and Its Manager's Quarters

The dispute centered around a substantial condominium building, a seven-story structure with a total floor area of 9,167.15 square meters. This building comprised various exclusive (privately owned) units: retail stores, parking spaces, and warehouses on the first and second floors, and 108 residential units located from the second floor upwards.

The focal point of the legal battle was the "manager's room" (kanrininshitsu). This space, measuring 37.35 square meters, was situated on the first floor. It was configured like a small apartment, featuring two Japanese-style tatami rooms, a kitchen, a toilet, a bathroom, a hallway, and its own entrance/exit door. Notably, this manager's room did not house any shared equipment for the condominium, such as alarm systems, central electrical panels, or master lighting controls. It had no telephone line directly linked to building management functions. The entrance was a steel door, lockable, allowing access to and from the outside without needing to pass through the adjacent management office.

Immediately next to this manager's room was the "management office" (kanri jimusho). This was a smaller area of 8.28 square meters, recognized as a common part of the condominium. It was strategically located, facing the main entrance hall and lobby, and featured a glass window and counter suitable for interacting with people entering or leaving the building and for monitoring such movements. Unlike the manager's room, the management office was equipped with essential common facilities: alarm systems for fire and water leaks, electrical distribution panels, and controls for the common area lighting. However, the management office lacked a toilet and was described as being too small to comfortably accommodate a resident manager or to adequately store management-related documents.

Crucially, the manager's room and the management office were physically connected. There was no difference in floor level between them, and a sliding glass door provided free passage from one to the other. This interconnectedness was not accidental. The original sales brochures distributed when the condominium units were first sold, as well as the schedule of management fees attached to the management consignment agreement, explicitly mentioned both a "management office" and a "manager's room." Furthermore, the condominium's architectural design plans (specifically, the finishing schedule) depicted the manager's room and the management office as a single, integrated unit labeled "Manager's Quarters."

The Seeds of Dispute: Ownership and Intended Use

The manager's room had its ownership preservation registration (a form of initial title registration) recorded in the name of Company Y, an entity affiliated with the original developer of the condominium. Another company, Company W, also an appellant in the Supreme Court case and part of the developer's group, was occupying the manager's room. Company W was also the entity with which the unit owners had their management consignment agreement.

A group of unit owners, H and five others (the plaintiffs/respondents), challenged this arrangement. They contended that the manager's room, by its nature and purpose, was a "part of the building that should be available for common use by all or some of the unit owners by reason of its structure" – in other words, a common area (or "common part," kyōyō bubun) as defined under Article 4, Paragraph 1 of Japan's Act on Unit Ownership of Buildings. Based on their shared co-ownership rights in what they claimed was a common area, they initiated legal action. Their demands were twofold: against Company Y, they sought the cancellation of the ownership preservation registration; and against Company W, they sought the surrender (eviction from) of the manager's room.

The Legal Journey: Differing Interpretations

The District Court's View: A Focus on Physical Independence

The initial trial at the District Court found in favor of the defendant companies. The court determined that the manager's room qualified as an "exclusive part" (sen'yū bubun) of the condominium, meaning it could be the subject of separate ownership. The reasoning was that the manager's room was sufficiently demarcated from other parts of the building by walls, floors, and ceilings to be suitable for independent physical control. Its layout (with living facilities and its own entrance) meant it had the external characteristics to be used independently as a residence or an office. Thus, the District Court concluded that the manager's room possessed both structural and utilitarian independence, making it ineligible as a common part and validating the claims of Company Y and Company W. H and the other unit owners' claims were dismissed.

The High Court's Reversal: Prioritizing Functional Integration

Dissatisfied, H and the other unit owners appealed to the High Court. The High Court overturned the District Court's decision. While acknowledging the manager's room did possess "structural independence" (i.e., it was physically a distinct unit), the High Court reached a different conclusion regarding its "utilitarian independence."

The High Court reasoned that the manager's room was a necessary component for the benefit of all unit owners in the condominium. It was not, in itself, well-suited for standalone use as a general residence or office unrelated to the building's management. Instead, its most natural and intended purpose was to be used integrally with the adjacent management office for the overall administration and upkeep of the entire condominium. This functional interdependence with the management office, which was undeniably a common area, led the High Court to conclude that the manager's room lacked utilitarian independence. Consequently, it should be classified as a common part under Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Act on Unit Ownership of Buildings. As such, it could not be the object of separate ownership. The High Court deemed Company Y's ownership registration invalid and Company W's occupation to be without legal basis, thereby granting the unit owners' demands.

This set the stage for Company Y and Company W to appeal to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling: Upholding Functional Necessity

On February 12, 1993, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered its judgment, dismissing the appeal from Company Y and Company W and upholding the High Court's decision.

The Supreme Court began by meticulously reiterating the facts as lawfully established by the High Court:

- The manager's room, with its 37.35 square meters, included two Japanese-style rooms, a kitchen, toilet, bathroom, hallway, and its own external entrance. It contained no common building equipment (alarms, panels, etc.) and had no dedicated telephone line for management. Its lockable steel door allowed direct external access without passing through the management office.

- The condominium was a large, seven-story building with 108 residential units forming the majority of the exclusive parts. No residential units were on the first floor where the manager's room was located.

- The manager's room was adjacent to common areas like the entrance hall, lobby, elevator, and stairs. The neighboring 8.28 square meter management office, a common part, had a counter facing the lobby, monitoring capabilities, and housed common equipment like alarm systems and electrical panels.

- Crucially, there was no step between the manager's room and the management office; a sliding glass door allowed free movement between them. The management office lacked a toilet – an essential facility if a manager were to be stationed there permanently – and was too small for practical storage of management documents.

- Promotional brochures for the condominium units and the schedule of management fees (part of the agreement between unit owners and Company W) explicitly listed both a "management office" and a "manager's room." The building’s design plans showed both spaces combined and labeled as "Manager's Quarters."

Synthesizing these facts, the Supreme Court reasoned as follows: The condominium was relatively large, with residential use predominating. Therefore, to ensure the smooth daily life of the unit owners and to maintain and preserve their living environment, it was necessary to have a manager stationed on-site to perform a wide range of management duties. The facts clearly indicated that the management office alone, given its small size and lack of essential amenities like a toilet, was insufficient for a manager to be permanently stationed there and to carry out their duties appropriately and smoothly.

From this, the Court concluded that the manager's room was intended to be used together and integrally with the management office. The two rooms were "functionally inseparable."

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that even if the manager's room possessed structural independence (which it did, due to its physical construction), it lacked "utilitarian independence" (riyōjō no dokuritsusei). Because it lacked this crucial utilitarian independence, the manager's room could not be the object of separate ownership. The High Court's judgment, which had reached the same conclusion, was affirmed as correct, and the appellants' arguments were found to be without merit. The precedents cited by the appellants were deemed distinguishable on their facts and not applicable to the present case.

Unpacking Japanese Condominium Law: The Concepts of "Exclusive Part" and "Common Part"

To fully appreciate the Supreme Court's reasoning, it's essential to understand the foundational concepts of Japanese condominium law, primarily derived from the Act on Unit Ownership of Buildings (Kubun Shoyū Hō).

Exclusive Part (Sen'yū Bubun)

The Act defines an "exclusive part" as "a part of a building that is the object of unit ownership" (Article 2, Paragraph 3). Unit ownership itself is defined as "ownership of a part of a building...which consists of structurally demarcated sections in a single building that can be independently used as residences, stores, offices, or warehouses..." (Article 1 and Article 2, Paragraph 1).

From these provisions, legal interpretation and scholarly commentary have established two key requirements for a portion of a building to qualify as an exclusive part:

- Structural Independence (Kōzōjō no Dokuritsusei): This refers to the physical demarcation of the space. The part must be separated from other parts of the building by elements like walls, floors, and ceilings, making it distinct and identifiable. The boundaries must be relatively permanent structural features, not temporary partitions like paper screens (fusuma or shōji). However, complete hermetic sealing is not required; for example, a first-floor parking garage with openings was recognized as structurally independent in a previous Supreme Court case.

- Utilitarian Independence (Riyōjō no Dokuritsusei): This means the demarcated part must be capable of being used independently for one of the purposes specified in the Act—residence, shop, office, warehouse, or other similar building uses. If a part cannot be independently used as a building in this sense, there is little practical value in recognizing separate ownership over it. This criterion often involves assessing:

- Whether the part has its own access from the outside or from a common hallway, without necessarily passing through another exclusive part.

- Whether the part possesses the necessary facilities for its intended use (e.g., a residence typically needs a kitchen and bathroom, though this isn't an absolute rule for all types of exclusive parts).

- The absence of common-use equipment within the part that is essential for other units or the building as a whole. However, the presence of some minor common equipment (like a shared drainage pipe, as seen in the aforementioned parking garage case) does not automatically negate utilitarian independence; it's a matter of degree.

The concepts of structural and utilitarian independence are often interrelated and assessed in conjunction.

Common Part (Kyōyō Bubun)

Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the Act defines "common parts" as:

- Parts of the building other than exclusive parts.

- Fixtures of the building that do not belong to an exclusive part.

- Attached buildings that are made common parts by the management agreement (as per Article 4, Paragraph 2).

Article 4 further elaborates:

- Paragraph 1 (Statutory Common Parts): "Hallways or staircases leading to several exclusive parts, and other parts of the building that should be available for common use by all or some of the unit owners by reason of its structure" are legally deemed common parts. These parts cannot be objects of separate ownership because they inherently lack either structural or utilitarian independence, or both. Examples include elevator shafts, main pipes and wiring, and foundations.

- Paragraph 2 (Contractual Common Parts - Kiyaku Kyōyō Bubun): Parts of a building that could qualify as exclusive parts (i.e., they meet the criteria for both structural and utilitarian independence) can still be designated as common parts by the condominium's management agreement or bylaws (kiyaku). An example might be a meeting room or a janitor's apartment that is structurally independent but dedicated to common use by agreement.

The manager's room in this case was argued by the plaintiffs to fall under Article 4, Paragraph 1 – a part that, by its nature and intended use, should be for common benefit, implying it lacked the requisite independence to be an exclusive part.

The Crux of the Matter: "Utilitarian Independence" Beyond Physical Form

The Supreme Court's decision in this case is particularly significant for its interpretation and application of "utilitarian independence." While the manager's room clearly had its own walls, door, kitchen, and bathroom (suggesting structural independence and a semblance of self-contained utility), the Court looked deeper.

The judgment pivoted on the functional necessity and intended operational integration of the manager's room with the management office. The Court considered:

- The Needs of the Condominium Community: A large residential complex requires effective management, often necessitating an on-site manager.

- The Inadequacy of Designated Common Facilities: The official "management office" was too small and ill-equipped to support a resident manager.

- The Designed Interconnectivity: The physical link (door, no step) and the labeling in plans and brochures as a unified "Manager's Quarters" clearly signaled an intention for joint use.

- Functional Inseparability: The manager's room, with its living facilities, was deemed essential to make the management function (centered in the management office) viable for a resident manager. One could not effectively function without the other in the context of this specific condominium's needs and design.

This approach signifies that "utilitarian independence" is not merely an abstract assessment of whether a space could be hypothetically used for a private purpose. Instead, it's a contextual evaluation that considers the space's role and function within the entire building, especially in relation to other common elements and the overall management scheme designed for the collective benefit of all unit owners.

The first instance court (District Court) had adopted a more atomistic view, focusing primarily on the physical attributes of the manager's room in isolation. It asked: "Can this room, by itself, be a dwelling or an office?" The Supreme Court, aligning with the High Court, took a more holistic and purposive approach: "Given the structure, design, and operational needs of this specific condominium, is this manager's room functionally independent, or is it an indispensable component of a larger common management facility?"

The decision highlights that even a space equipped with residential amenities may be classified as a common part if its primary, intended, and functionally necessary role is inextricably tied to the management and communal use of the property. The Court effectively stated that the "utility" in "utilitarian independence" must be assessed in light of the overarching purpose for which such spaces are created in a condominium setting. If that purpose is fundamentally communal and integrated with other common service areas, then true independence is lacking.

This ruling underscores the importance for developers and condominium associations to clearly define and demarcate exclusive and common parts from the outset, not just in terms of physical boundaries but also in terms of intended use and functional integration. When a space, despite having features of a private unit, is designed and essential for the common administration and welfare of the building, it is likely to be viewed as a common part, irrespective of attempts to register it as separate property.

Concluding Thoughts: A Functional Approach to Property Rights

The 1993 Supreme Court decision concerning the manager's room provides a crucial clarification in Japanese condominium law. It reinforces that the determination of whether a building part is exclusive or common hinges on a dual test: structural independence and utilitarian independence. More importantly, it establishes that utilitarian independence must be assessed not just by looking at the intrinsic capabilities of the space itself, but by considering its intended function, its relationship with other parts of the building, and its role in the overall management and use of the condominium as a collective entity.

This pragmatic and functional approach ensures that spaces genuinely intended and necessary for the common good of all unit owners are preserved as common areas, safeguarding the operational integrity and habitability of condominium communities. It serves as a reminder that in shared living environments, the lines of ownership are drawn not only by physical walls but also by the purpose and function those spaces serve for the community as a whole.