The Thief Who Came Back: A Japanese Ruling on the Time Limit for Robbery

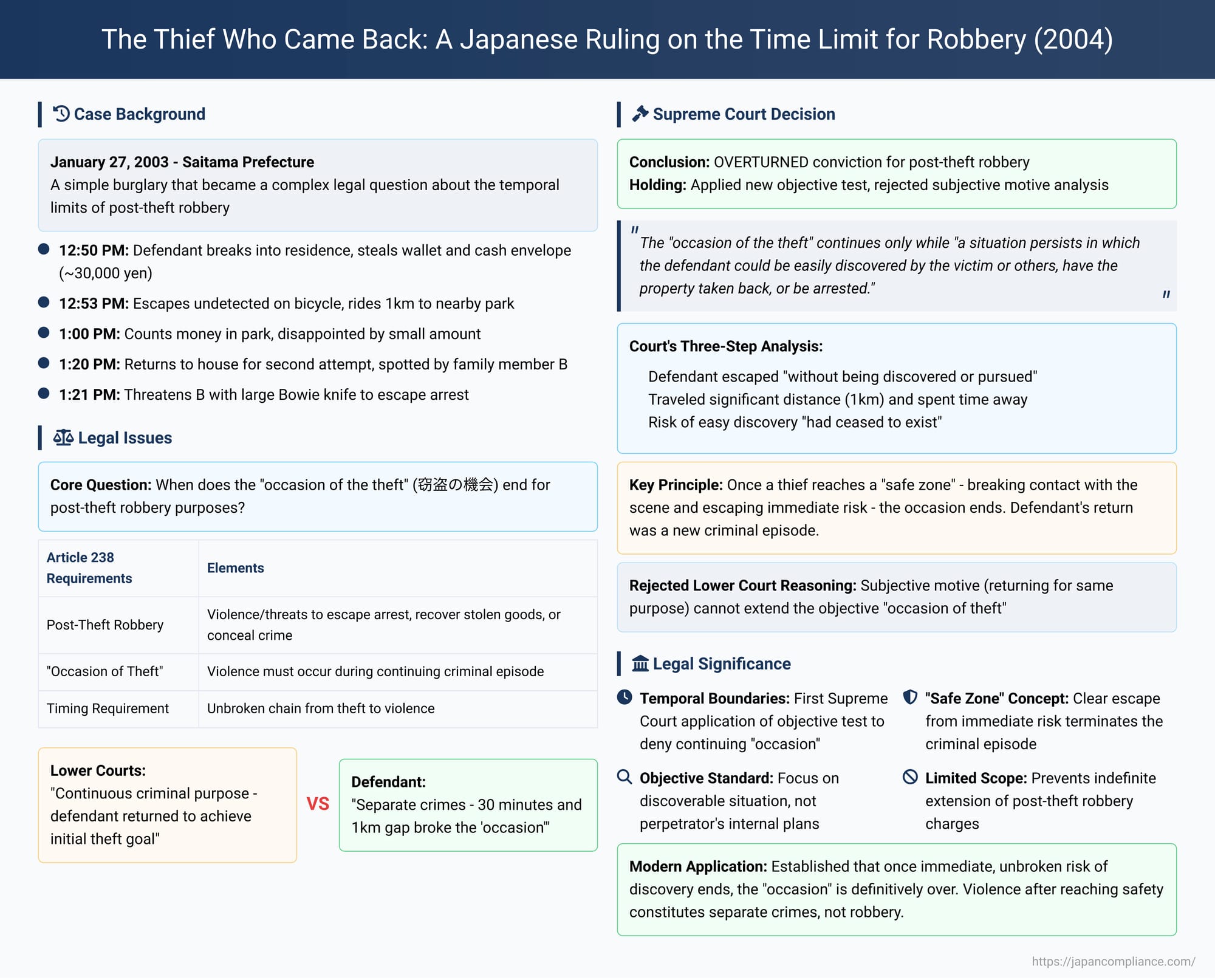

In the eyes of the law, when does a theft end? The question may seem simple, but its answer is critical for a unique Japanese crime known as "post-theft robbery" (jigo gōtō). This provision treats a thief who uses violence or threats to escape arrest, recover stolen goods, or conceal their crime as a full-fledged robber, subject to much harsher penalties. However, a crucial, unwritten requirement is that the violence must occur "on the occasion of the theft" (settō no kikai).

But how long does this "occasion" last? What if a thief gets away clean, leaves the area, and then decides to return, only to be caught and resort to violence? Does the "occasion of the theft" restart? This very question was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on December 10, 2004. The ruling established a clear, objective test for when the "occasion of the theft" is definitively over, providing a vital limit on the scope of this serious crime.

The Facts: The Dissatisfied Thief's Return Trip

The case began with a simple burglary. At around 12:50 PM on January 27, 2003, the defendant broke into a residence to steal valuables. He took a wallet and an envelope containing cash from the living room. Just a few minutes after entering, he left through the front door and fled the scene on a bicycle. Critically, he got away "without being discovered or pursued by anyone."

He rode approximately 1 kilometer to a nearby park. There, he stopped to count his loot and was disappointed to find it was only about 30,000 yen. Believing there must be more valuables in the house, he made a fateful decision: he would go back for a second try.

He rode his bicycle back to the residence. At around 1:20 PM, roughly 30 minutes after his initial entry, he opened the front door again. This time, however, he realized someone was inside. He immediately closed the door and retreated to the parking area outside the gate. Just then, a family member, B, who had returned home, spotted him and realized he was the intruder. As B moved to apprehend him, the defendant, in order to escape arrest, pulled a large Bowie knife from his pocket, displayed the blade, and waved it at B. As B flinched and backed away, the defendant made his escape.

The Legal Framework: "Post-Theft Robbery" and the "Occasion of the Theft"

The defendant was charged with post-theft robbery under Article 238 of the Penal Code. This statute was created based on the criminological reality that a cornered thief will often resort to violence, and that this situation is just as dangerous as a conventional robbery. Therefore, the law "promotes" the crime from theft to robbery.

However, case law and legal theory have long held that this promotion only applies if the subsequent violence is intrinsically linked to the initial theft. This link is conceptualized as the "occasion of the theft." If the violence occurs outside this "occasion," it is treated as a separate crime (e.g., assault or threats), and the perpetrator is not a robber. Courts have historically analyzed this "occasion" by looking at various factual patterns, such as a thief being actively pursued from the scene, or a thief lingering at the scene and being discovered. The most complex scenario, and the one relevant here, is when a thief leaves and then returns.

The Lower Courts' Ruling: A Continuous Criminal Purpose

The lower courts, including the Tokyo High Court, found the defendant guilty of post-theft robbery. Their reasoning focused on the defendant's subjective motive. The High Court held that the defendant returned to the house "to achieve his initial goal of theft." Because his intent was continuous, they reasoned, his return was part of the same criminal episode, and therefore the threat with the knife occurred "on the occasion of the theft."

The Supreme Court's Reversal: A New, Objective Standard

The Supreme Court overturned the conviction for post-theft robbery and remanded the case. The Court rejected the lower court's focus on the defendant's motive and instead applied a new, objective test that it had recently established in a 2002 decision.

The test for whether the "occasion of the theft" is ongoing is whether:

"a situation persists in which the defendant could be easily discovered by the victim or others, have the property taken back, or be arrested."

Applying this objective standard to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court found that the "occasion" of the first theft was clearly over. Its reasoning was methodical:

- After the initial theft, the defendant "left the scene of the crime... without being discovered or pursued by anyone."

- He traveled a significant distance (1 km) and spent "a certain amount of time" away from the scene.

- Therefore, "it must be said that the situation in which the defendant could be easily discovered... had ceased to exist."

Because the direct, continuous risk of discovery and apprehension related to the initial theft had ended, the "occasion" was severed. The Court concluded:

"Thus, even if the defendant later returned to the scene of the crime for the purpose of committing theft again, it cannot be said that the said threat made at that time was made on the occasion of the [initial] theft."

The defendant's threat with the knife was a new criminal act, but it could not be used to retroactively transform the completed, and now concluded, first theft into a robbery.

Analysis: The "Safe Zone" and the Irrelevance of Motive

The Supreme Court's 2004 decision is highly significant because it was the first time the Court used its new, objective test to deny the continuation of the "occasion of the theft." It established a clear and logical limit on the crime's scope.

The ruling effectively introduces the concept of a "safe zone." Once a thief has successfully broken contact with the scene, escaped any pursuit, and reached a point of temporary safety where the immediate, unbroken risk of discovery has passed, the "occasion" of the original crime is over. The defendant's trip to a park 1 kilometer away, where he had the time and peace of mind to stop and count the stolen money, was a clear entry into such a safe zone.

This objective standard is far more predictable and legally sound than the lower court's reliance on the defendant's subjective motive. As legal commentary on the case points out, a thief's internal plans should not determine the objective legal status of their situation. Whether the defendant always planned to return, or decided to do so on a whim, is irrelevant. The objective fact is that the immediate, confrontational situation connected to the first crime had ended.

Conclusion: Drawing a Clear Line in the Sand

The 2004 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling that provides a clear and principled limit on the powerful charge of post-theft robbery. It establishes that the "occasion of the theft" is not an indefinite period defined by a perpetrator's lingering criminal ambitions. Instead, it is an objective situation of immediate and continuous risk.

The core principle is now clear: once a thief has successfully gotten away, breaking the chain of events that could lead to easy discovery and apprehension for the original crime, the "occasion" is over. Any violence used after that point is a new crime, distinct from the first. This ruling provides crucial clarity in the law, ensuring that the severe penalties for robbery are reserved for situations where theft and violence are truly and inextricably linked in a single, unbroken chain of events.