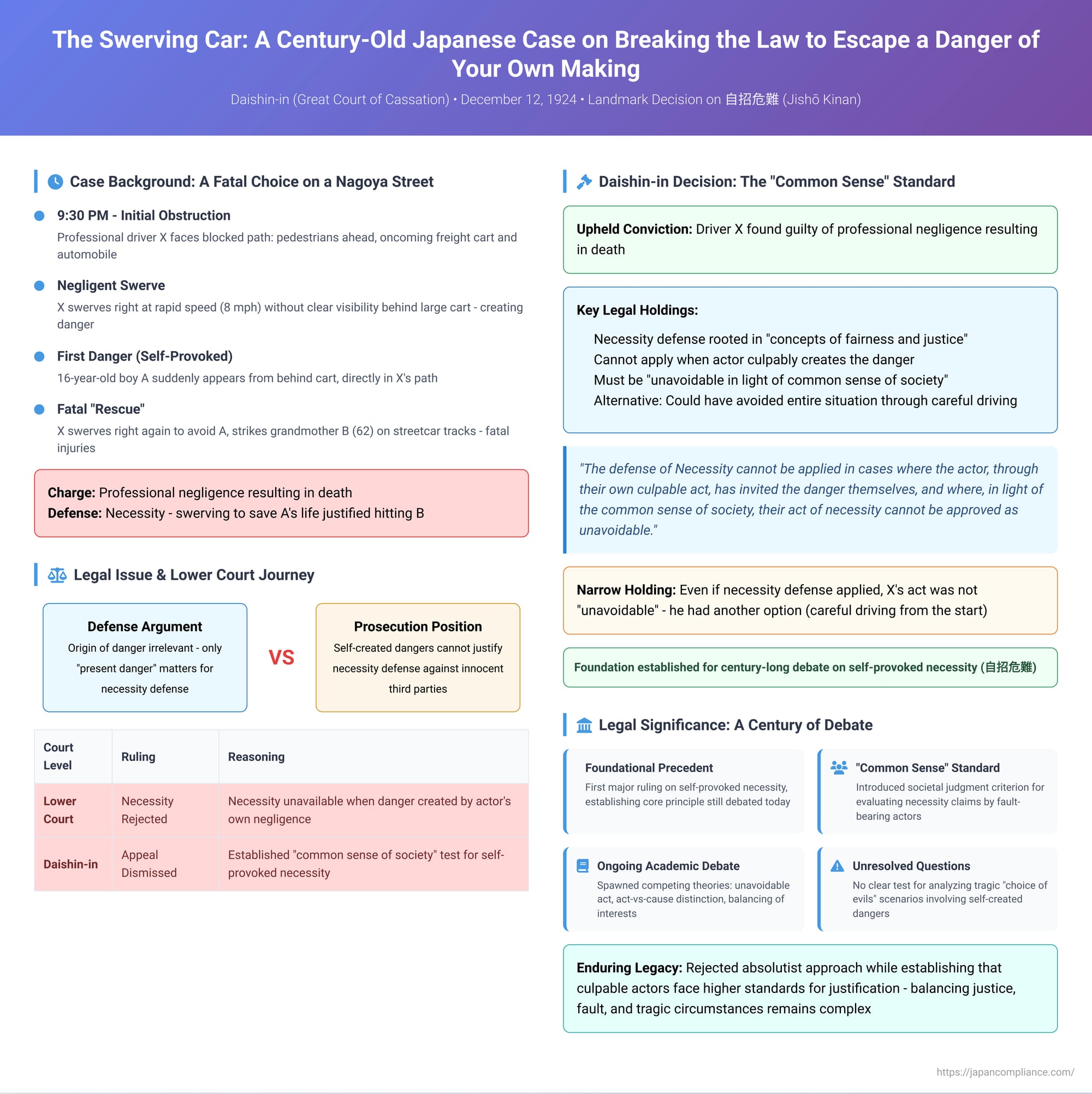

The Swerving Car: A Century-Old Japanese Case on Breaking the Law to Escape a Danger of Your Own Making

Decision Date: December 12, 1924

The doctrine of "Necessity" is one of the most compelling and ethically fraught areas of criminal law. It posits that an act that would normally be criminal can be justified if it is done to avert a present and greater danger. But this justification rests on a foundation of innocence. What happens when the person claiming the defense of Necessity is the very one who created the danger in the first place? Can a person negligently set a crisis in motion and then legally harm an innocent bystander to escape the consequences?

This profound question was at the heart of a foundational decision issued on December 12, 1924, by Japan's highest pre-war court, the Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation). The case, involving a professional driver whose negligence on a dark street led to a fatal choice, established the legal principle of "self-provoked necessity" (jishō kinan) and has served for a century as the starting point for a complex and still-unresolved debate on the limits of justification for dangers of one's own making.

The Factual Background: A Cascade of Dangers on a Nagoya Street

The incident occurred around 9:30 PM on a wide street in Nagoya. The defendant, X, was a professional automobile driver. The sequence of events unfolded rapidly:

- The Obstruction: Driving south on the left side of the road, X found his path blocked. Several pedestrians walking in the same direction refused to yield despite his horn. Further ahead, a large freight cart laden with cargo was approaching him, traveling north on the same side of the street. To compound matters, another automobile was also approaching from the front, making it impossible for X to proceed straight ahead.

- The Negligent Act: To navigate the obstruction, X swerved his car to the right, crossing toward the center of the road to pass the oncoming freight cart. He did so at what the court described as a "rapid" speed of about 8 miles per hour (approx. 13 km/h), which was considered fast for the conditions of the time. This act was negligent because it was nighttime and the large cart completely obscured his view of anything or anyone who might be behind it. A prudent driver would have slowed or stopped to ensure the way was clear.

- The First Danger (Self-Provoked): As X was speeding past the cart, a 16-year-old boy, A, suddenly appeared from behind it, attempting to cross the street directly in the car's path. X was now faced with the immediate danger of hitting and likely killing A—a danger created entirely by his own negligent driving.

- The "Rescue" and Final Result: To avoid hitting A, X reacted by swerving sharply to the right once more. This evasive maneuver caused his vehicle to strike B, A's 62-year-old grandmother, who was walking on the streetcar tracks in the center of the road. B suffered fatal injuries, including broken ribs and a ruptured liver.

X was charged with professional negligence resulting in death. His defense was that his final act of swerving and hitting B was a justified act of Necessity, undertaken to save the life of A.

The Legal Journey: Can a Negligent Driver Claim Necessity?

The case presented the courts with a novel legal problem. The defendant's argument was that the "present danger" to A's life justified his act of swerving, even if that act foreseeably resulted in harm to B.

- The Lower Court's Ruling: The lower court rejected this defense. It ruled that the doctrine of Necessity, as a matter of fairness, requires that the danger "was not brought about by the intent or negligence of the person performing the act of necessity." Because X had created the peril to A through his own negligence, he was barred from claiming the defense.

- The Appeal to the Daishin-in: The defense appealed this ruling. The core of the appeal was the argument that the origin of the danger is irrelevant to the Necessity defense. All that matters, the defense argued, is that a "present danger" existed that needed to be averted.

The Daishin-in's Foundational Ruling

The Daishin-in dismissed the appeal and upheld the conviction. In its reasoning, it articulated a principle that would define the law on self-provoked necessity for the next century.

The Core Principle on Self-Provoked Necessity:

The Court began by explaining the philosophical basis of the Necessity defense, stating that it is rooted in "concepts of fairness and justice." It then laid down its key principle:

The defense of Necessity "cannot be applied in cases where the actor, through their own culpable act, has invited the danger themselves, and where, in light of the common sense of society, their act of necessity cannot be approved as unavoidable."

This statement established that a person who culpably creates a crisis cannot automatically claim the protection of the Necessity defense. The justifiability of their actions must be judged by a higher standard, filtered through the "common sense of society."

The Court's Holding on the Facts:

Interestingly, while the Court established this powerful new principle, its ultimate reason for convicting the defendant in this specific case was more straightforward. The commentary points out that the statement on self-provoked necessity was technically obiter dictum (a judicial comment made in passing). The Court's formal holding was that the defendant's claim failed on a different element of Necessity: supplementarity, or the requirement that the act be truly unavoidable.

The Court found that X had another option: he could have avoided hitting B simply by not driving so negligently in the first place. Since he had "another method to avoid [the collision]," his act of striking the grandmother was not truly an "unavoidable" act. Despite this narrow holding, it was the Court's broader statement on self-provoked danger that would become the ruling's enduring legacy.

A Deeper Dive: The Unsettled Legal Theory of Jishō Kinan

The Daishin-in's 1924 decision opened a new field of legal debate in Japan that remains unsettled to this day. While it rejected an all-or-nothing approach, it did not provide a clear, step-by-step test for analyzing these cases. Subsequent legal scholarship has proposed several competing theories to fill the gap.

- The "Unavoidable Act" Approach: This theory, which follows the Daishin-in's narrow holding, focuses on whether the defendant's final act was truly a last resort. The defendant's prior fault in creating the situation is used as context to determine if other, better choices were available.

- The "Act-in-Itself" vs. "Cause" Distinction: A more recent theory attempts to separate the final act from its cause. It might argue that the act of swerving to save A was, in isolation, a justified act of Necessity. However, the initial act of negligent driving remains a crime, and the defendant can be punished for that. Critics argue this theory is too narrow and cannot resolve all scenarios.

- The "Balancing of Interests" Theory: This influential view argues that a person's fault in creating a danger diminishes the legal value of the interest they seek to protect. For example, if a driver negligently creates a situation where they must choose between their own life and that of an innocent pedestrian, the law should value the pedestrian's life more highly. This case is more complex, as the defendant X was trying to save a third party, A. This theory would argue that since A was not at fault, the value of his life is not diminished, and X's act to save him could be justified—but only if it met the other strict requirements of Necessity.

These competing theories show that while the 1924 ruling established the problem of self-provoked necessity, it did not provide a final answer. The question of how to balance the competing interests and assess culpability in these tragic "choice of evils" scenarios remains a subject of intense academic debate.

Conclusion: A Century-Old Question with No Easy Answer

The 1924 Daishin-in decision in the case of the swerving car is a foundational moment in Japanese criminal law. It rejected an absolutist approach to the doctrine of Necessity and firmly established the principle that a person who culpably creates a crisis cannot automatically justify harming an innocent person to escape it. The Court's declaration that such an act must be "unavoidable in light of the common sense of society" introduced a crucial element of culpability and fairness into the analysis.

While the Court's final decision rested on the narrower ground that the driver had other options, its broader statement on self-provoked danger has resonated for a century. It leaves behind a complex legacy, forcing the legal system to continually weigh the principles of justice and fault when one person's negligence creates a tragic choice between two innocent lives.