The State's Duty to Protect: Japan's Landmark 1975 "Safety Obligation" Ruling

When individuals serve the public, does the state, as their employer, bear a fundamental responsibility to ensure their safety beyond statutory compensation schemes? A pivotal decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 25, 1975, answered this question affirmatively, establishing the principle of the state's "duty of care" (安全配慮義務 - anzen hairyo gimu) towards its public servants. This ruling marked a significant evolution in Japanese administrative and civil law, enhancing legal protections for those working in public service.

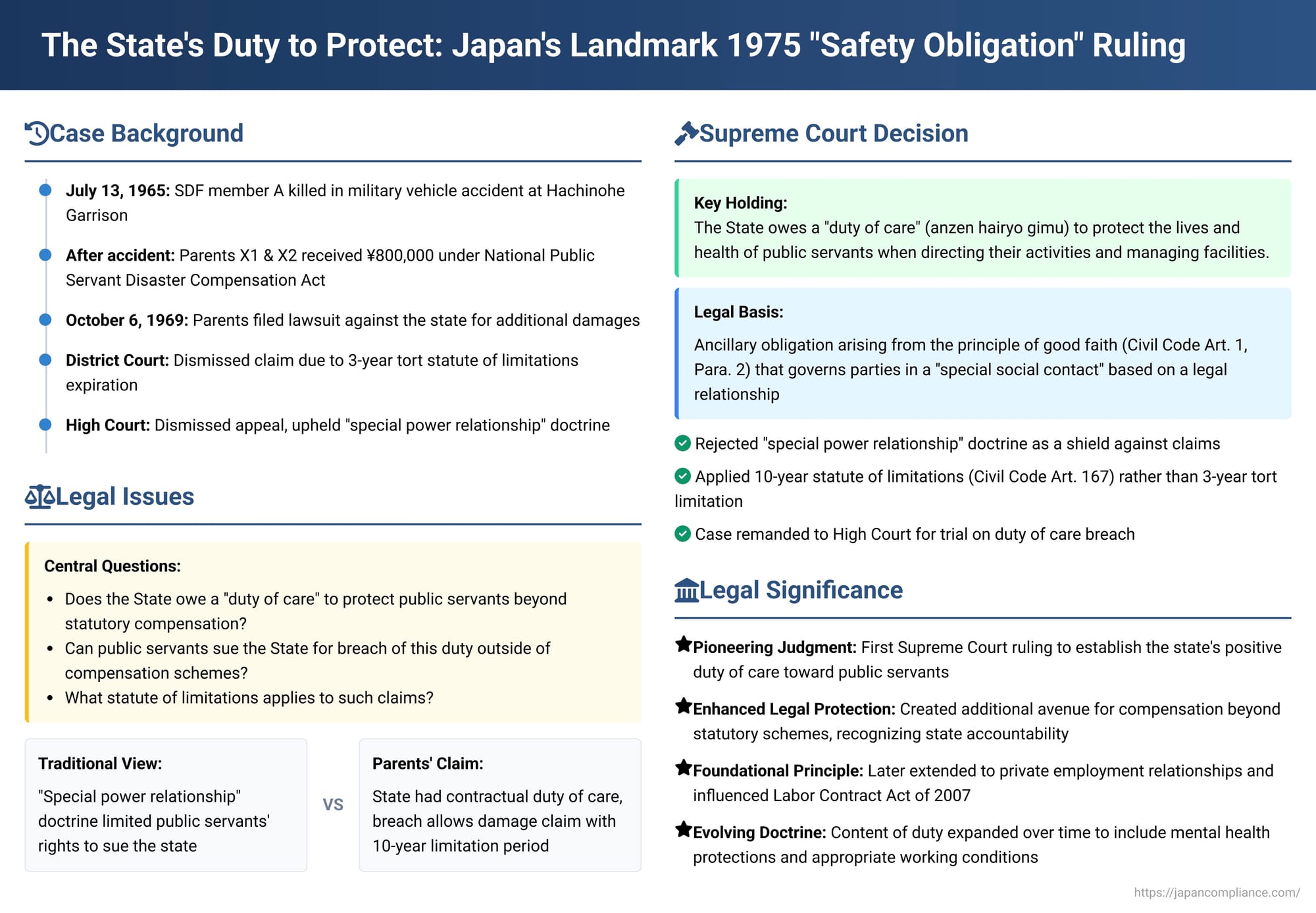

The Tragic Incident and the Legal Journey

The case arose from a fatal accident involving a member of Japan's Self-Defense Forces (SDF).

- The Accident: On July 13, 1965, Mr. A, an SDF member, was performing vehicle maintenance at the SDF Hachinohe Garrison. He was tragically struck and killed instantly by a large military vehicle being operated by another SDF member, Mr. B.

- Initial Compensation: Mr. A's parents, X1 and X2, received a sum of approximately 800,000 yen under the National Public Servant Disaster Compensation Act. This Act provides a no-fault compensation system for work-related injuries, illnesses, or death of public servants.

- The Lawsuit: Several years later, in July 1969, the parents learned that they might have grounds to seek further damages from the state (Y). Consequently, on October 6, 1969, they filed a lawsuit against the state, initially basing their claim on the Auto Liability Security Act (which governs compensation for traffic accidents).

- Lower Court Dismissals:

- The Tokyo District Court (first instance) dismissed the parents' claim. It determined that the parents became aware of the damage and the identity of the party at fault (for tort purposes) on July 14, 1965. Therefore, by the time the lawsuit was filed in October 1969, the three-year statute of limitations for tort claims had expired.

- The parents appealed to the Tokyo High Court, adding a crucial new argument: they claimed damages based on a breach of contract, specifically alleging that the state, as Mr. A's employer, had failed in its "duty of care" to ensure his safety.

- The High Court also dismissed their claim. It upheld the District Court's ruling on the expiration of the tort claim's statute of limitations. More significantly, regarding the newly added claim based on a breach of duty of care, the High Court invoked the concept of a "special power relationship" (tokubetsu kenryoku kankei). This traditional, and by then increasingly criticized, legal doctrine characterized the relationship between the state and its public servants as one where the state held extraordinary authority, and public servants had limited rights to sue the state for work-related harm outside the specific statutory compensation frameworks. Based on this doctrine, the High Court concluded that the state did not owe a contractual duty of care that could give rise to a claim for damages.

Mr. A's parents then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Affirming the State's Duty of Care

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of February 25, 1975, overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for reconsideration, laying down foundational principles regarding the state's obligations to its employees.

Establishment of the "Duty of Care" (Anzen Hairyo Gimu)

- The Court unequivocally recognized that the state owes a "duty of care" to its public servants.

- This duty entails an obligation for the state, when establishing and managing places, facilities, or equipment for the performance of public duties, or when managing the public duties performed by public servants under the direction of the state or their superiors, to take due care to protect the lives and health of those public servants from danger.

- The Court noted that the specific content of this duty of care would naturally vary depending on factors such as the type of public service, the rank and position of the public servant, and the particular circumstances in which the duty arises (e.g., routine work, training, or emergency deployments for SDF members).

Basis in the Principle of Good Faith (Shingisoku)

Critically, the Supreme Court grounded this duty of care not in any single explicit statutory provision but in a broader, fundamental legal principle:

- The duty of care, the Court stated, should be generally recognized as an ancillary obligation arising from the principle of good faith (shingisoku, Civil Code Article 1, Paragraph 2) that governs the relationship between parties who have entered into a "special social contact" (tokubetsu na shakaiteki sesshoku no kankei) based on a legal relationship.

- The Court found no logical basis to interpret this principle differently or to exclude its application in the context of the relationship between the state and its public servants. This was a significant departure from views that might have seen the public employment relationship as exempt from such general private law principles.

Rationale for Imposing the Duty on the State

The Court provided compelling reasons for affirming this duty:

- Enabling Diligent Public Service: Public servants are bound by primary duties, such as the duty to devote themselves to their work and to obey laws and the lawful orders of their superiors. For public servants to fulfill these obligations with peace of mind and in good faith, it is essential and indispensable that the state, as their employer, bears a corresponding duty to care for their safety.

- Presupposition for Disaster Compensation Systems: The Court also reasoned that existing statutory schemes for public servant disaster compensation (like the National Public Servant Disaster Compensation Act) operate on the implicit premise that the state already has this underlying duty of care. These compensation systems are designed to address work-related injuries or fatalities that might occur even if the state has fulfilled its duty to take preventative safety measures.

Rejection of the "Special Power Relationship" as a Bar to Claims

By establishing the duty of care based on general principles of good faith applicable to legal relationships involving "special social contact," the Supreme Court effectively dismantled the High Court's reliance on the "special power relationship" doctrine as a shield against such claims. The ruling signaled a move towards recognizing that public servants, despite their unique role, are entitled to fundamental protections common to other employment relationships.

Statute of Limitations for Breach of Duty of Care Claims

A crucial aspect of the ruling for the plaintiffs was the Court's determination on the applicable statute of limitations for claims arising from a breach of this duty of care by the state:

- The Court held that the five-year statute of limitations stipulated in Article 30 of the Public Accounting Act (which generally governs monetary claims by or against the state) does not apply to claims for damages resulting from the state's failure to fulfill its duty of care towards public servants.

- The rationale for the five-year limit in the Public Accounting Act is primarily administrative convenience – the need to settle the state's financial rights and obligations promptly. This, the Court found, is relevant for routine monetary claims but not necessarily for damage claims arising from breaches of the duty of care, as such incidents are typically sporadic and not so frequent as to overwhelm administrative processes if a longer period applies.

- Moreover, the state's obligation to compensate for damages caused by a breach of its duty of care is, in its purpose and nature (i.e., aimed at fair reparation for harm based on principles of equity), no different from damage compensation obligations between private individuals.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the statute of limitations for such claims against the state is the ten-year period provided by Article 167, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code (as it existed at that time for general obligations/contractual claims).

Outcome and Remand

Given these findings, the Supreme Court ruled that the High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of the law by dismissing the plaintiffs' claim based solely on the "special power relationship" doctrine. The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further examination and trial based on the principles articulated, particularly concerning the potential breach of the state's duty of care. This meant that the plaintiffs' claim, now framed under the duty of care with a 10-year statute of limitations, was not time-barred and could proceed on its merits.

Significance and Broader Implications of the Ruling

The 1975 Supreme Court decision was a landmark with far-reaching implications:

- Pioneering Judgment on State Liability: It was the first Supreme Court ruling to explicitly establish the state's positive duty of care towards its public servants, deriving this duty from the general principle of good faith. This was a significant jurisprudential development, moving beyond relying solely on tort law principles for state liability in such contexts.

- Enhanced Rights for Public Servants: The decision substantially bolstered the legal avenues for public servants (or their families) to seek redress for work-related injuries or fatalities. It clarified that statutory no-fault compensation did not preclude claims for full damages if a breach of the state's duty of care could be proven.

- Extension of Developing Private Sector Principles: Interestingly, the concept of an employer's duty of care to employees was already emerging in lower court rulings concerning private sector employment relationships. The Supreme Court's 1975 decision was notable because it robustly applied this principle to the public sector before the Court had issued a definitive ruling affirming it for private employment (which it did in a subsequent case in 1984). This underscores the fundamental nature of the duty. (The duty of care for private employers was later explicitly included in Japan's Labor Contract Act of 2007, though this Act itself does not apply to most public servants who are covered by separate legal frameworks.)

- Foundation for a General Principle of Duty of Care: The Supreme Court's reasoning was framed broadly, anchoring the duty of care in the "principle of good faith" applicable to parties in a "special social contact based on a legal relationship". This broad formulation suggested that the duty's relevance could extend beyond the direct state-public servant employment context. Indeed, subsequent Supreme Court rulings recognized a similar duty of care owed by principal contractors to the employees of their subcontractors in certain situations. The principle has also been discussed in relation to other relationships, such as between schools and students, although its application in every context is not automatic and has been subject to further judicial refinement. For instance, a later Supreme Court case in 2016 clarified that the state does not owe this specific type of good-faith-based duty of care to pre-trial detainees, highlighting that the nature of the relationship and the absence of a voluntary undertaking of obligations (as in employment) are critical factors.

- Evolution of the Content of the Duty: While the 1975 judgment established the existence of the duty, its specific content is inherently context-dependent and has evolved through subsequent case law. Later Supreme Court decisions involving SDF personnel clarified that this duty is not an absolute guarantee against all harm (a "result obligation") but rather an obligation to take all reasonably possible measures to create a safe working environment (a "means obligation"). In more recent years, particularly with rising concerns about overwork and mental health, the duty of care has been interpreted by courts to include ensuring appropriate working conditions and taking steps to mitigate health risks, including those related to mental health, sometimes even requiring employers to be proactive if signs of distress are apparent.

- Historical Advantage of the Statute of Limitations: For many years, a significant practical advantage of basing a claim on a breach of the duty of care (as a contractual or quasi-contractual obligation) rather than on tort was the longer statute of limitations – ten years under the old Civil Code, compared to three years from the time of knowledge for torts. This was clearly a critical factor in the 1975 case. It is important to note that amendments to the Japanese Civil Code (which came into effect in April 2020) have largely unified the statute of limitations periods for claims related to personal injury or death, whether arising from tort or breach of contract/obligation. This has somewhat diminished the historical procedural advantage of the duty of care claim in this specific regard, leading to renewed academic discussion about its distinct substantive role compared to tort law.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1975 judgment in the case of the deceased SDF member was a watershed moment in Japanese law. It firmly established that the state, like any employer, has a fundamental duty to care for the safety and health of its public servants, a duty grounded in the overarching principle of good faith. This decision provided an important legal avenue for public servants and their families to seek proper redress when this duty is breached, supplementing the existing statutory compensation systems. By moving away from outdated doctrines like the "special power relationship" that had previously limited state accountability, the ruling not only enhanced the rights of public servants but also paved the way for a broader understanding and application of the duty of care principle across various legal relationships in Japan.