The Spoken Word as a Public Act: How Japan's "Theory of Propagation" Defines Defamation

In the law of defamation, the element of "publicity" is paramount. A defamatory statement must be made "publicly" to be a crime. But what does "publicly" mean? Does it require a large crowd, a broadcast, or a published article? What if a damaging statement is made to only one or two people in the privacy of a home? Can such an intimate communication be considered a "public" act?

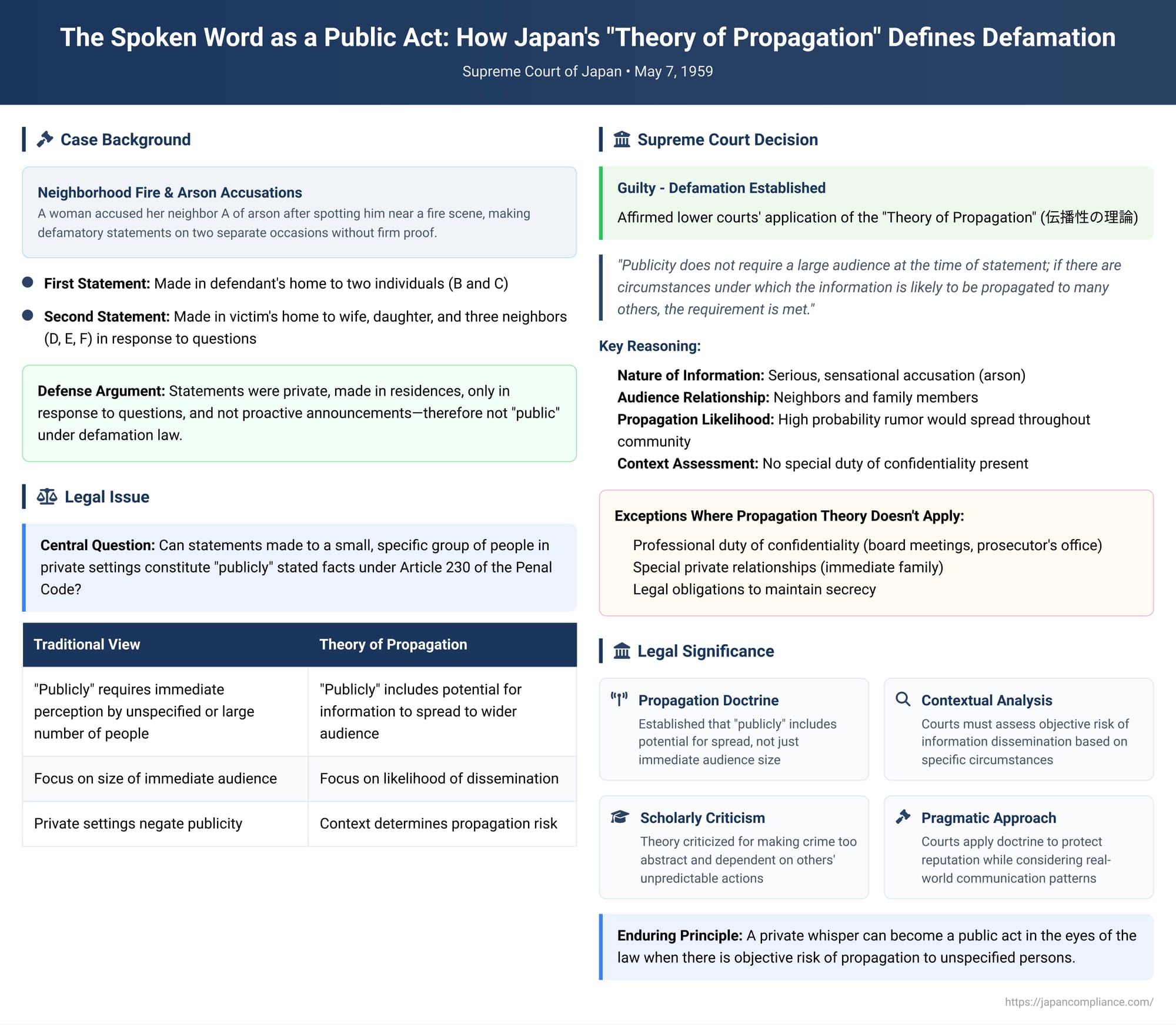

A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on May 7, 1959, addressed this very question, solidifying a uniquely Japanese legal doctrine known as the "theory of propagation" (denpansei no riron). This theory holds that a statement made to even a small, select group can be deemed "public" if there is a reasonable likelihood that it will spread, or propagate, to a wider, unspecified audience. This ruling and the doctrine it affirmed remain central to understanding the scope of defamation law in Japan today.

The Facts: A Neighborhood Accusation

The case arose from a small fire in a neighborhood. The defendant, after seeing a fire near her home, spotted a man nearby whom she believed to be her neighbor, A. Subsequently, she made statements on two separate occasions accusing A of arson, despite having no firm proof.

The first statement occurred in the defendant's own home, where she spoke to two individuals, B and C. The second took place in the victim's own home, where, in response to questions, she repeated the accusation to A's wife and eldest daughter, as well as to three other neighbors, D, E, and F.

The defendant's lawyer argued that these were not public statements. They were made in private residences, only in response to questions, and were not a proactive announcement of fact. Therefore, they could not be considered a "public" statement of fact as required by the crime of defamation.

The Legal Concept of "Publicly" in Defamation

The crime of defamation in Japan, outlined in Article 230 of the Penal Code, is designed to protect a person's social standing or external reputation. A key element of the crime is that a fact that could lower this reputation must be stated "publicly" (kōzen). The established definition of "publicly" is a state in which an unspecified or large number of people can perceive the information.

The central issue in this case was whether statements made to a small, specific group of people could ever meet this standard. The lower courts thought so. The court of first instance found the defendant guilty, reasoning that "publicity" does not require a large audience at the time of the statement; if there are circumstances under which the information is likely to be propagated to many others, the requirement is met. The High Court agreed, stating that the defendant made her statement in a condition where it could reach the perception of an unspecified or large number of people, making the question of whether she was asked first irrelevant to the establishment of the crime.

The Supreme Court ultimately affirmed this view, holding that under these facts, the defendant had indeed stated a fact "publicly".

The "Theory of Propagation": Expanding the Definition of "Publicly"

The court's decision is a clear application of the "theory of propagation." This doctrine holds that the test for publicity is not the size of the immediate audience, but the potential for the information to disseminate. A statement made to just a few people can satisfy the "publicly" requirement if the context makes it likely to spread.

In this case, the defendant was speaking to neighbors and family members about a serious and sensational accusation—arson. The courts determined that the nature of the information and the relationships of the listeners made it highly probable that the rumor would not remain contained within that small group but would inevitably spread throughout the local community. The potential for propagation was inherent in the situation.

Drawing the Line: When is a Private Statement Not "Public"?

The theory of propagation does not mean, however, that every private conversation is at risk of being deemed "public." Japanese courts have carefully limited the doctrine's application, primarily in situations where there is an objective reason to believe the information will not spread. Case law provides clear examples of where the line is drawn:

- Duty of Confidentiality: In a 1937 case, defamatory statements made during a corporate board of directors meeting were found not to be public because the attendees had a duty to maintain confidentiality, eliminating the risk of propagation. Similarly, a 1959 decision found that insulting remarks made in a prosecutor's office, heard only by the prosecutor and a clerk, were not public due to their professional duty of secrecy. In a 1983 High Court case, a letter containing allegations against a teacher sent only to the school principal, the head of the education board, and the PTA president was also deemed not public for the same reason.

- Special Private Relationships: In another 1959 case, a statement made at home, heard only by the defendant's wife, mother, and housekeeper, was found to lack publicity, presumably because the tight, familial relationship created a barrier to wider dissemination.

These cases demonstrate that the courts apply the theory by making a concrete, case-by-case assessment of the objective risk of propagation. The theory is negated when a clear, objective factor—like a legal or professional duty of confidentiality—is present.

A Contentious Doctrine: Scholarly Critiques of the Theory

Despite its consistent use by the courts, the theory of propagation is highly controversial among legal scholars in Japan, with many criticizing it on several grounds:

- Conflating Act and Result: Critics argue that "publicly" is a required element of the act of defamation, not a potential result of that act. The theory improperly shifts focus from the perpetrator's action to its possible consequences.

- Over-Abstraction: Defamation is already an "abstract endangerment" crime, meaning it punishes the creation of a risk of harm, not actual harm. The theory of propagation, by punishing the risk of a risk (the possibility that a statement might become public), makes the crime even more abstract.

- Dependency on Others: The theory makes the establishment of a crime dependent on the unpredictable will of the listener. Whether the listener chooses to spread the rumor—an act outside the original speaker's control—can determine the speaker's criminal liability, which many find irrational.

- Blurring Perpetration and Complicity: A person who tells a defamatory fact to a single newspaper reporter, who then publishes it, is arguably an instigator or accomplice to the reporter's public act of defamation. The theory of propagation, however, risks treating the initial speaker as the principal offender, "upgrading" their criminal liability. Indeed, a 1931 case treated such an act as instigation of defamation, not perpetration.

Conclusion: A Pragmatic Judicial Approach

While the scholarly critiques are powerful, the Japanese judiciary has consistently maintained its stance. The 1959 Supreme Court decision cemented the "theory of propagation" as a key, pragmatic tool for assessing defamation. The courts do not apply it blindly; rather, they use it to make a concrete judgment about the objective danger a statement poses to a person's reputation.

The ruling's legacy is that the "publicity" of a statement is not a simple headcount of listeners. It is a qualitative assessment of the situation. When a person makes a defamatory statement of a sensational nature to individuals who have no special duty or relationship that would ensure their silence—such as neighbors in a close-knit community—the law presumes that the statement has been released into the wild, with a high objective risk that it will propagate. In such cases, the private whisper becomes, in the eyes of the law, a public act.