The Spark and the Flame: A 1950 Japanese Ruling on When Arson Becomes a Completed Crime

The crime of arson is one of the most serious offenses against public safety, threatening not only property but also human life and community stability. But in the eyes of the law, at what precise moment does the act of setting a fire cross the critical threshold from a criminal "attempt" to a "completed" felony? Is it when the match is first struck? When the flame touches its intended target? Or is it only when the fire grows into an uncontrollable conflagration? The answer to this question determines not only the severity of the charge but also the point at which an offender can no longer abandon their course of action and avoid the most serious consequences.

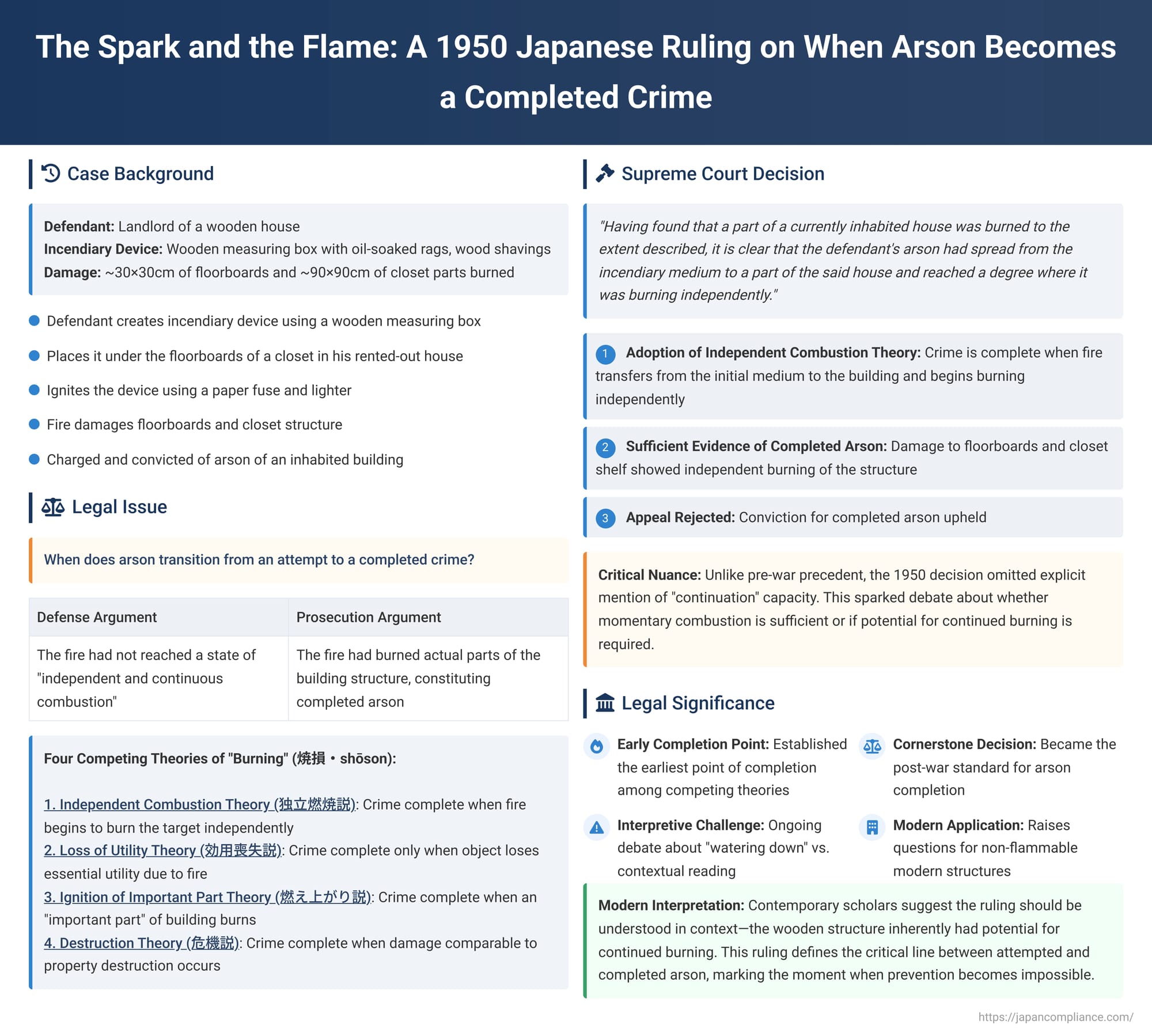

A pivotal May 25, 1950, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan addressed this fundamental issue. In a case involving a landlord who set fire to his own rented-out wooden house, the Court established the post-war standard for the consummation of arson, a principle that continues to be a cornerstone of Japanese criminal law today.

The Facts: The Fire in the Closet

The case involved a defendant who had rented out his wooden, single-story house to a family. While the family was living there, he secretly entered and set a fire. His method was deliberate:

- He fashioned an incendiary device from a wooden measuring box (gogōmasu).

- Inside, he placed rags soaked in machine oil and packed it with wood shavings.

- He positioned the device under the floorboards of a closet (oshiire).

- He then used a piece of twisted paper as a fuse, which he lit with a lighter.

The fire took hold, and the lower court found that it had burned and destroyed specific parts of the house itself: "approximately a one-shaku square (about 30x30 cm) of the floorboards in the three-tatami-mat room, and approximately a three-shaku square (about 90x90 cm) each of the closet's floorboards and its upper shelf." Based on this, the defendant was convicted of arson of a currently inhabited building.

On appeal to the Supreme Court, the defense argued that this damage was minor and, crucially, that the lower court had failed to prove the fire had reached a state of "independent and continuous combustion." They contended that without such a finding, the crime was not legally complete.

The Legal Landscape: Four Theories of "Burning"

The defendant's argument tapped into a long-standing and complex debate in Japanese legal theory over the definition of "burned" (shōson), the term used in the Penal Code to signify the completion of arson. Traditionally, four main theories have competed for acceptance:

- The Independent Combustion Theory (dokuritsu nenshō setsu): This is now the prevailing view. It holds that the crime is complete at the moment the fire transfers from the initial fuel source or incendiary device (the "medium") and begins to burn the target object (the building) on its own. This theory marks the earliest point of completion among the four.

- The Loss of Utility Theory (kōyō sōshitsu setsu): This was once the prevailing view. It argues that the crime is not complete until the object has lost a significant part due to the fire and, as a result, has lost its essential utility or function. This marks the latest point of completion.

- The Ignition of Important Part Theory (moeagari setsu): An intermediate theory suggesting the crime is complete when an "important part" of the building begins to burn. It has been criticized for the ambiguity of what constitutes an "important part."

- The Destruction Theory (kiki setsu): Another intermediate theory, this one posits that the crime is complete when the object is damaged to a degree comparable to that required for the separate crime of property destruction.

The debate revolves around several axes: the proper interpretation of the word "burn" in the statute, the appropriate moment to recognize the public danger inherent in arson, and the need for a clear and predictable legal standard.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Adopting the "Independent Combustion" Standard

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's appeal. It found the lower court's detailed description of the damage to the floorboards and closet shelf to be sufficient. The Court declared:

"Having found that a part of a currently inhabited house was burned to the extent described, it is clear that the defendant's arson had spread from the incendiary medium to a part of the said house and reached a degree where it was burning independently."

With this statement, the Court affirmed the conviction and, in doing so, gave its clear endorsement to the Independent Combustion Theory. This decision established that the critical moment is not when the building has lost its function or is substantially destroyed, but when the fire has "taken hold" on the structure itself, independent of the initial fuel source.

Analysis: The Subtle but Crucial Nuance of "Independent Combustion"

While the 1950 decision is widely seen as adopting the Independent Combustion Theory, a closer look at legal history reveals a subtle but important nuance.

- The Missing Word: "Continuation": Before this ruling, the pre-war Supreme Court (the Great Court of Cassation) had also followed an independent combustion standard. However, its definition explicitly required that the fire must have the capacity to continue its combustion independently. The rationale was that only at this point does the fire pose an inevitable threat of total destruction and thus a true public danger. The 1950 Supreme Court decision, however, notably omitted the word "continuation."

- The "Watering Down" Problem: This omission led some in legal practice to interpret the standard as having been "watered down." A simplified understanding emerged: any momentary, independent combustion on the building itself, even if it quickly self-extinguished, was enough to complete the crime.

- Modern Challenges and Evolving Theories: This simplified view creates significant problems when applied to modern, non-flammable structures like concrete buildings.

- It could mean that a fire from an incendiary device that creates immense heat and toxic gas, rendering a building uninhabitable without the structure itself burning, would not constitute a completed crime. This concern has led to the proposal of a "New Loss of Utility Theory."

- Conversely, it could mean that the momentary, independent burning of a small patch of flammable paint or wallpaper would constitute the completed, serious felony of arson, a seemingly disproportionate result.

- Re-interpreting the 1950 Case in Context: Modern legal scholarship suggests that the 1950 decision should not be read in a vacuum. The case involved a wooden house. A fire ignited under the floor of a wooden closet that spreads to the floorboards inherently possesses the potential to continue burning and spread throughout the structure. Therefore, the Supreme Court likely omitted an explicit mention of "continuation" because it was self-evident from the facts of the case. The fire had not just sparked; it had taken root in the building's flammable structure.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1950 ruling in the case of the closet fire remains a foundational decision in Japanese arson law. It cemented the "independent combustion" of the building itself as the legal moment of completion for this grave offense. While the text of the ruling is concise, its interpretation is rich with complexity. The consensus of modern legal thought is that it should not be seen as a simple "any spark will do" rule. Instead, it is understood to require a fire that has truly transferred to the building's structure and possesses the inherent potential to continue and spread, thereby realizing the profound public danger that the law of arson is designed to prevent. The decision thus stands as a crucial landmark, defining the fine line between a criminal attempt and an irreversible catastrophe.