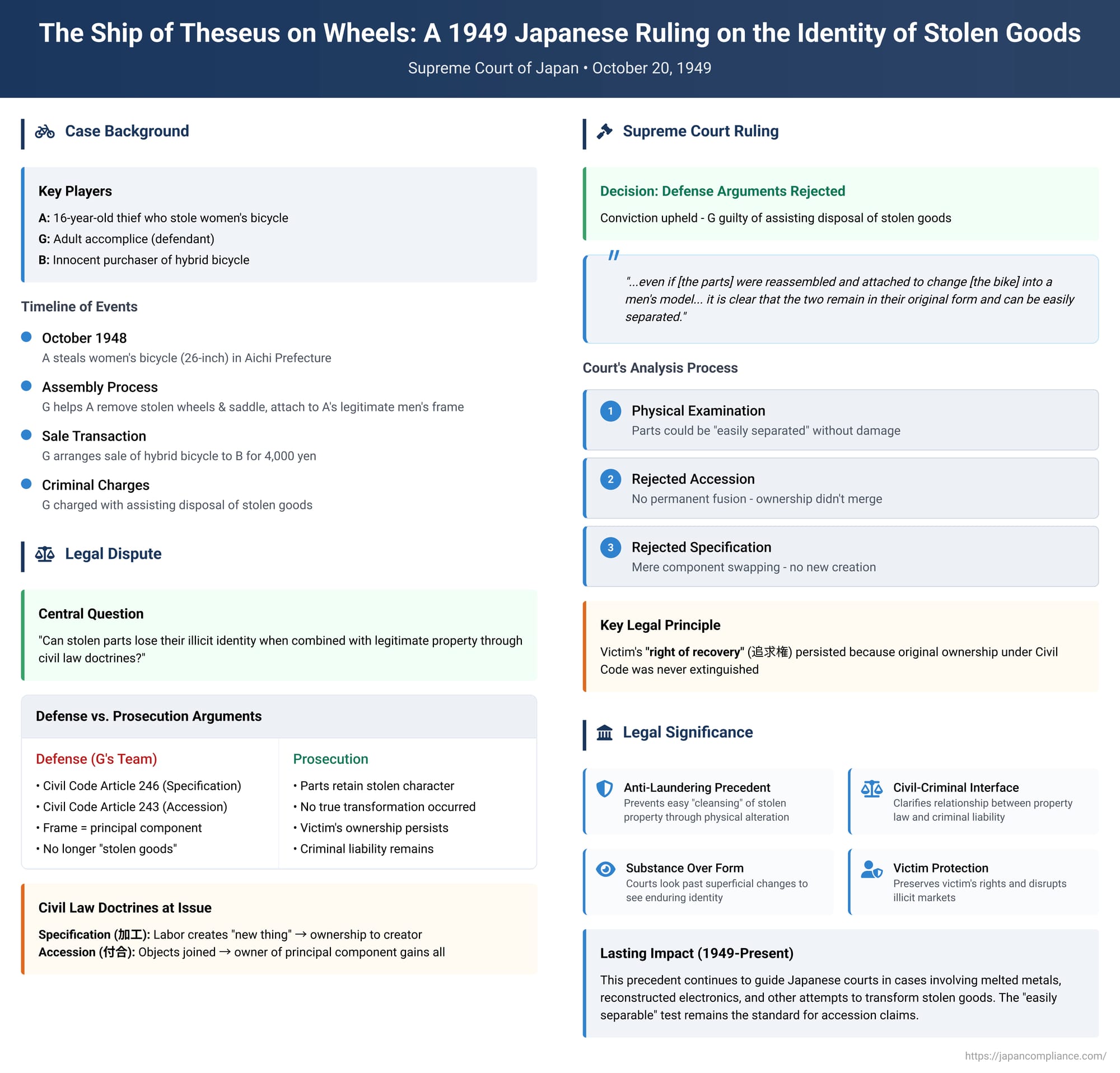

The Ship of Theseus on Wheels: A 1949 Japanese Ruling on the Identity of Stolen Goods

Imagine a skilled mechanic takes a powerful, stolen engine and expertly installs it into the chassis of a legally owned, but otherwise unremarkable, car. They then offer to sell you the resulting vehicle. Are you buying a legitimate car with a questionable part, or are you buying stolen property? At what point does a stolen object, when combined with legitimate property, lose its illicit identity? This is not merely a philosophical puzzle like the Ship of Theseus; it is a critical legal question that challenges the very definition of property and crime.

On October 20, 1949, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a foundational judgment that tackled this precise issue. The case, arising from the chaos of the post-war era, involved not a car, but a bicycle. Yet, its legal reasoning established a durable principle about the nature of stolen goods (zōbutsu) that remains a cornerstone of Japanese criminal law. It explores the fascinating intersection of civil property law and criminal liability, asking a simple but profound question: can a thief or their accomplice "launder" a stolen item by physically transforming it?

The Facts: A Hybrid Bicycle

The case originated in Aichi Prefecture in October 1948. The facts presented to the court were straightforward. A 16-year-old boy, whom we will call A, had stolen a used 26-inch women's bicycle. He then sought the help of an adult, G.

Together, G and A dismantled the stolen bicycle. They took its most valuable components: the two wheels (complete with tires and tubes) and the saddle. A, the young thief, was in possession of another bicycle frame—this one a men's style—which he owned legally. With G's assistance, the stolen wheels and saddle were affixed to A's legitimate men's bicycle frame. This process created a new, hybrid bicycle.

G's involvement did not stop at assembly. He then acted as a broker, arranging the sale of this newly created men's bicycle to a third party, B, for a price of 4,000 yen. G was fully aware that the key components of the bicycle he was helping to sell were stolen. When the authorities intervened, G was charged with the crime of assisting in the disposal of stolen goods (zōbutsu gasen), a precursor to the modern offense of accessory to the disposal of stolen property.

The Defense's Ingenious Argument: A Civil Law Shield

At trial, G's defense team did not contest the basic facts. They didn't deny that the wheels and saddle were stolen or that G had helped sell the resulting bicycle. Instead, they mounted a sophisticated legal argument grounded not in criminal law, but in Japan's Civil Code. Their strategy was to argue that the bicycle, at the moment of its sale, was no longer "stolen property" in the eyes of the law.

The defense's argument hinged on two related principles of property law: "specification" (kakō) and "accession" (fugō).

- The Argument from Specification (Kakō): This principle, found in Article 246 of the Civil Code, deals with situations where a person applies labor to an object belonging to another. If the labor creates a "new thing" whose value is substantially greater than the original material, ownership of the new object may pass to the creator. The defense argued that by combining the stolen parts with the frame and creating a functional men's bicycle, A had engaged in an act of specification.

- The Argument from Accession (Fugō): This principle, under Article 243, applies when objects belonging to different owners are joined together. In the case of movable property, the owner of the "principal component" acquires ownership of the entire composite object. The defense asserted that the bicycle frame was the principal component. By attaching the stolen wheels and saddle (the accessory components) to his own frame, A, the owner of the principal component, became the legal owner of the entire hybrid bicycle.

The conclusion of this logic was powerful: If, through the rules of the Civil Code, ownership of the wheels and saddle had legally transferred from the original victim to A, then they ceased to be stolen property. And if the bicycle G helped sell was legally A's property, G could not be guilty of trafficking in stolen goods. He was merely helping a young man sell his own possession. The lower courts rejected this defense, and G appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Pragmatic Rejection

The Supreme Court decisively rejected the defense's argument. The Court's reasoning was clear, direct, and focused on the physical reality of the objects in question.

The justices noted that the lower court had found that G helped A take the wheels and saddle from the stolen women's bicycle and attach them to the men's frame. The key passage of the judgment reads:

"...even if [the parts] were reassembled and attached to change [the bike] into a men's model as stated in the judgment, it is clear that the two [the frame and the parts] remain in their original form and can be easily separated. Therefore, one cannot say they were attached in a state where they could not be separated, nor can one say, as the argument claims, that work was performed on A's men's bicycle frame using the women's bicycle's wheels and saddle."

In this short paragraph, the Court dismantled the entire civil law defense.

- Against Accession: The Court found that the legal test for accession was not met. The wheels and saddle were not permanently fused to the frame. They could be "easily separated" without damaging either the parts or the frame. Because they were not inextricably linked, ownership of the parts did not merge with the ownership of the frame.

- Against Specification: The Court dismissed this argument even more swiftly. This was not a case of creating a new thing from raw materials. It was merely swapping components. The wheels were still wheels; the saddle was still a saddle. No fundamental transformation occurred.

The Court's ultimate conclusion was that the original owner, the victim of the theft, had never lost their property rights to the wheels and saddle. Because the victim's ownership and right to recover the items persisted, the items retained their character as zōbutsu—stolen goods. G's conviction was upheld.

The Deeper Doctrine: The "Right of Recovery"

To fully understand the Court's logic, one must appreciate a core tenet of Japanese law on this subject. For an item to be considered "stolen property" for the purposes of criminal law, the original victim must still possess a legally enforceable "right of recovery" (tsuikyūken). This right is rooted in their continued ownership under the Civil Code.

This creates a direct and crucial link between the two bodies of law. If an event occurs—such as a good-faith purchase by an innocent third party, or a legal transfer of ownership through doctrines like accession or specification—that extinguishes the original owner's property rights under the Civil Code, the item's status as "stolen property" for criminal purposes also vanishes. This is why G's defense was so clever: if they could prove a transfer of ownership under the Civil Code, the criminal charge would necessarily fail.

The 1949 Supreme Court decision is significant because it shows the judiciary's approach to resolving this tension. While acknowledging the link to the Civil Code, the criminal courts have consistently interpreted its provisions in a manner that supports the policy goals of criminal law.

Policy Over Pure Doctrine?

A review of Japanese case law, both before and after this 1949 decision, reveals a distinct pattern. When faced with a thief's attempt to alter stolen goods, the courts are exceedingly reluctant to find that a "new thing" has been created or that a true "accession" has occurred.

- On Specification (Kakō): Courts have held that melting down stolen aluminum lunch boxes into ingots, crushing lead pipes into blocks, or refining gold from stolen amalgam are mere "changes in form," not the creation of a new object that would transfer ownership. These acts do not cleanse the items of their stolen nature. The policy goal is clear: to prevent thieves from easily "laundering" stolen precious metals and other materials.

- On Accession (Fugō): The bicycle case was an easy call because the parts were designed for removal. The legal test is whether separation would cause damage or incur excessive cost. The Court simply applied this test and found it was not met.

This line of jurisprudence has led some legal scholars to suggest that criminal courts are guided by a strong undercurrent of criminal policy. The primary objective is to suppress the market for stolen goods and prevent thieves from profiting from their crimes. To achieve this, courts will narrowly construe any Civil Code provision that might allow a thief or their accomplice to legalize their possession through physical alteration. The fear is that a broad interpretation would effectively provide a "how-to" guide for laundering stolen property, rendering the laws against trafficking in such goods toothless.

However, the scope of this decision has important limits. The Court's reasoning is heavily tied to the facts: G and A both knew the parts were stolen. The outcome might be different in a hypothetical scenario involving an innocent party. For instance, if a high-end custom bicycle builder, acting in good faith, purchased the stolen wheels and saddle and incorporated them into a valuable, unique frame of their own creation, a court might well find that "specification" had occurred. In that case, the builder would likely be granted ownership of the final product under the Civil Code. The parts would lose their illicit character, and anyone who subsequently sold that bike would not be committing a crime.

Conclusion: A Lasting Legacy

The 1949 "Bicycle Case" is more than a historical curiosity. It stands as a vital precedent that clarifies the identity and persistence of stolen property. It affirms that one cannot easily extinguish the "stain" of theft through simple physical combination, especially when the parts are easily separable and the actors are aware of the property's origins.

The decision masterfully navigates the intersection of civil and criminal law. While respecting the structure of the Civil Code, the Supreme Court's interpretation is ultimately pragmatic, ensuring that property law cannot be used as a simple tool to subvert the goals of criminal justice. It sends a clear message that has resonated through Japanese law for decades: the law will look past superficial changes to see the enduring identity of a stolen object, protecting the rights of the victim and disrupting the illicit economy that theft creates.