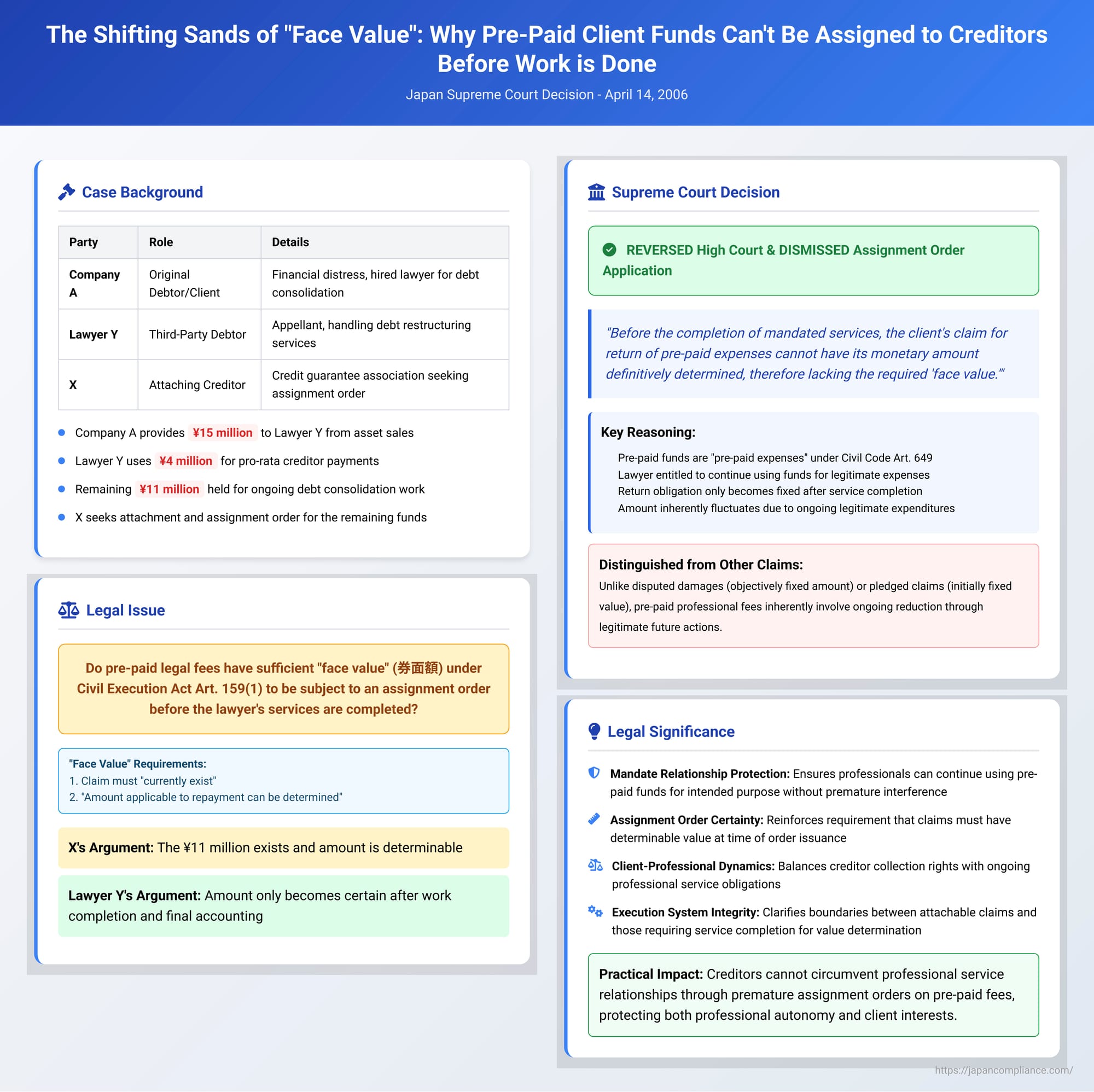

The Shifting Sands of "Face Value": Why Pre-Paid Client Funds Can't Be Assigned to Creditors Before a Lawyer's Work is Done – A 2006 Japanese Supreme Court Case

Date of Decision: April 14, 2006

Case Name: Appeal Against Dismissal of Execution Appeal Against Assignment Order (Permitted Appeal)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: 2005 (Kyo) No. 33

Introduction

In the world of debt collection in Japan, an "assignment order" (転付命令, tenpu meirei) is a powerful tool. It allows a creditor who has attached a monetary claim owed by a third party to their debtor to have that claim transferred directly to themselves, effectively in lieu of payment. This means the creditor steps into their debtor's shoes and can collect from the third party. However, for an assignment order to be valid, the attached monetary claim must possess what is known as a "face value" (券面額, kenmengaku) at the time the order is issued. This "face value" isn't necessarily its actual market worth, but rather a determinable nominal monetary amount.

But what happens when the attached claim is for funds held by a professional, like a lawyer, as a pre-payment for ongoing services? Is the client's right to the return of any unused portion of these funds considered to have a sufficiently certain "face value" to be subject to an assignment order before the professional's work is complete? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this nuanced question in a decision on April 14, 2006.

The Case of the Unsettled Retainer: A Lawyer, a Client, and a Creditor

The facts of the case were as follows:

- Company A (Original Debtor): Facing financial distress after its parent company became insolvent, Company A engaged Lawyer Y to handle its debt consolidation and restructuring affairs.

- Lawyer Y (Third-Party Debtor/Appellant): The lawyer retained by Company A.

- X (Attaching Creditor/Respondent): A credit guarantee association that held a monetary claim against Company A, confirmed by a final judgment.

To facilitate the debt consolidation process, Company A provided Lawyer Y with approximately JPY 15 million. These funds were sourced from the sale of Company A's assets, such as a factory. Lawyer Y used about JPY 4 million of this sum to make pro-rata payments to some of Company A's creditors (not including X and one other). The remaining balance of approximately JPY 11 million was managed by Lawyer Y to cover further expenses related to the ongoing debt consolidation work.

X, seeking to recover its claim against Company A, applied to the court for an attachment order and an assignment order targeting Company A's right to the return of this remaining JPY 11 million from Lawyer Y (referred to as "the Claim").

The Lower Courts' Decisions:

- The court of first instance (the execution court) issued both the attachment order and the assignment order as requested by X.

- Lawyer Y, as the third-party debtor, appealed against the assignment order portion, arguing that the Claim was not suitable for such an order.

- The High Court, however, dismissed Y's appeal. It reasoned that the Claim (A's right to the return of unused pre-paid fees from Y) did exist at that moment, and the amount that would eventually be applied to repayment could, in its view, be determined. Therefore, the High Court concluded that the Claim possessed the requisite "face value" under Article 159(1) of the Civil Execution Act.

Lawyer Y, disagreeing with the High Court, sought and obtained permission to appeal to the Supreme Court. Y’s central argument was that the final amount to be returned by Y to Company A would only become certain after all debt consolidation negotiations and related tasks were completed. Thus, the value of the Claim at the time the assignment order was issued could not be definitively determined, making the High Court's finding of a "face value" an error in interpreting the Civil Execution Act.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No "Face Value" Before Services Are Complete

The Supreme Court, in its decision on April 14, 2006, reversed the High Court's decision and the original court's assignment order. It ultimately dismissed X's application for the assignment order concerning the Claim.

The Court's reasoning was grounded in the nature of pre-paid expenses in a mandate relationship (like that between a client and a lawyer):

- Nature of the Funds Held by Lawyer Y: The approximately JPY 11 million being managed by Lawyer Y constituted "pre-paid expenses" (前払費用, maebarai hiyō) as understood under Article 649 of the Japanese Civil Code. This article stipulates that if expenses are required to manage affairs entrusted under a mandate, the mandator (client) must, upon the mandatary's (lawyer's) request, make an advance payment for those expenses.

- Functioning of Pre-paid Expenses: Such pre-paid funds are specifically provided to cover the costs associated with the mandated task (in this case, Company A's debt consolidation). The understanding is that as the mandatary (Lawyer Y) incurs legitimate expenses while performing these services, those expenses are to be drawn from these pre-paid funds.

- Timing of the Return Obligation: Critically, the mandatary (Lawyer Y) becomes obligated to return any remaining balance of these pre-paid expenses to the mandator (Company A) only after the mandated services have been fully completed and a final accounting is made.

- Claim Amount Becomes Fixed Only at Completion: Consequently, the Supreme Court reasoned that Company A's claim for the return of any unused portion of these pre-paid expenses only becomes fixed and certain in its amount when Lawyer Y's debt consolidation work is finished.

- Effect of Attachment on Ongoing Services: The Court further clarified that even if a creditor of the client (like X) attaches the client's potential claim for the return of these pre-paid expenses, this attachment does not prevent the mandatary (Lawyer Y) from continuing to perform the mandated services. Lawyer Y remains entitled, and indeed obligated, to use the pre-paid funds to cover necessary expenses incurred in carrying out the debt consolidation for Company A.

- Conclusion on "Face Value": Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded that before the completion of the mandated debt consolidation services, Company A's claim against Lawyer Y for the return of pre-paid expenses cannot have its monetary amount definitively determined. Therefore, it does not possess the "face value" required by Article 159(1) of the Civil Execution Act and is not eligible to be the subject of an assignment order.

Since the debt consolidation work undertaken by Lawyer Y for Company A was still ongoing at the time the assignment order was issued, the Claim was deemed unsuitable for such an order.

Deep Dive into "Face Value" and Its Implications

The concept of "face value" (券面額) is central to the Japanese assignment order system.

- Purpose of an Assignment Order: An assignment order serves as a mechanism for an attaching creditor to receive direct satisfaction. The attached monetary claim is transferred to the creditor at its "face value," and to that extent, the creditor's original claim against their debtor (the execution claim) and any associated execution costs are deemed to have been paid (Civil Execution Act Arts. 159, 160). This offers the creditor a chance for exclusive satisfaction, bypassing potential competition from other creditors, but it comes with the risk that if the third-party debtor is insolvent or the assigned claim proves uncollectible, the creditor bears that loss.

- Requirement for "Face Value": Because an assignment order aims for a clear and immediate transfer and satisfaction, the law requires that the targeted claim has a "face value." This means the claim must be for a monetary amount that can be expressed as a definite sum at the time the assignment order is issued. This is about the nominal value, not necessarily its actual market or recovery value.

- Supreme Court Definition of "Face Value": A prior Supreme Court decision (April 7, 2000, referenced in the commentary as "e61") established two key conditions for a claim to have "face value":

- It must "currently exist as a claim."

- Its "amount applicable to repayment can be determined."

When Does "Face Value" Become Contentious?

The requirement of a determinable amount poses challenges for certain types of claims:

- Continuous Future Claims / Claims with Conditions Precedent: Claims for future rent, future salary installments, or retirement benefits (payable only upon retirement) are generally attachable. However, they are typically considered to lack "face value" for assignment order purposes because their actual accrual or precise amount at a future date is uncertain. Similarly, a claim for the return of a security deposit before the lease has ended and damages (if any) have been assessed is problematic.

- Claims Subject to Counter-Performance: For example, a seller's claim for the purchase price, where payment is conditional upon the simultaneous delivery of goods. While academically debated, Japanese court practice has often held such claims to possess "face value" and thus be eligible for assignment orders. However, execution courts are often unaware of such counter-performance obligations unless the attaching creditor declares them.

- Claims with Factually Undetermined Amounts: Consider a tort claim for damages where liability is established but the quantum of damages is still disputed, or a claim for auto liability insurance proceeds after an accident but before the insurer has agreed on the payout amount. Recent court practice tends to affirm that such claims do have "face value." The reasoning is that the claim (and its underlying value) exists objectively from the moment the tort or insured event occurred; the amount is merely subject to factual dispute or assessment, not inherently indeterminate.

- Claims Subject to Prior Encumbrances: If a monetary claim is already subject to a pledge (a form of security interest), can it still have a "face value" for an assignment order by another creditor? The Supreme Court decision of April 7, 2000, affirmed that such claims do possess "face value" and are eligible for assignment (though the assignee takes the claim subject to the pledge).

Why Pre-Paid Expenses for Ongoing Services Are Different

The Supreme Court's 2006 decision regarding pre-paid lawyer's fees carves out a distinct category.

- The Nature of Pre-Paid Expenses for Mandated Services (Civil Code Art. 649): The Court relied on its earlier interpretation (a Supreme Court decision from June 12, 2003) of funds pre-paid to a lawyer for debt consolidation. That 2003 decision clarified that:

- Upon payment, such funds leave the client's direct control and come under the lawyer's control and responsibility, to be used according to the terms of the mandate.

- Concurrently, the lawyer incurs an obligation to the client for the eventual return of any unused portion of these funds.

- This return obligation is progressively reduced as the lawyer incurs and debits legitimate expenses. The final amount to be returned is only settled upon the completion of all mandated tasks and a final accounting.

- The 2006 Decision's Core Finding: The April 2006 decision built directly on this understanding. The crucial point is that the lawyer (Y) not only can but must continue to use the pre-paid funds (the JPY 11 million) to cover necessary expenses for Company A's debt consolidation, even after X attached A's claim for the return of these funds. This right and duty to expend the funds for A's benefit persists.

- Indeterminable Amount at Time of Assignment Order: Because these legitimate expenditures by the lawyer will continue after an assignment order might be issued (if it were deemed valid), the final sum that will remain to be returned to Company A (and thus to X via the assignment) is inherently unknowable and not fixed at the moment the assignment order is issued. It fails the second prong of the "face value" test: its "amount applicable to repayment can not be determined" until the lawyer's work is concluded.

Distinguishing from Other Claims with Post-Assignment Uncertainties:

- Simple Monetary Claims or Disputed Damages: Even a straightforward debt might be disputed after an assignment order. However, in such cases, the claim's amount is considered objectively fixed as of a certain point in time (e.g., the date the loan was due, the date the tort occurred). Later disputes don't change this initial objective fixedness. This is why disputed tort claims can still have "face value."

- Pledged Claims: If a claim subject to a pledge is assigned, the pledgee might later enforce their pledge, reducing or extinguishing the value of the claim for the assignee. However, the assignment order initially transfers the claim at its existing nominal value. The subsequent reduction due to the pledge's enforcement is a separate event affecting an already transferred asset. This doesn't negate the initial "face value."

- The Present Case (Pre-Paid Expenses): The claim for the return of pre-paid professional fees is unique because its very nature involves the amount fluctuating downwards due to legitimate, ongoing actions (the lawyer's work) that occur after the potential issuance of an assignment order. The amount is not objectively fixed at the time of the order; it is inherently contingent on future events integral to the mandate.

The PDF commentary also briefly touches upon whether such a claim might fail the first prong of the "face value" test – "currently existing as a claim." While the 2003 Supreme Court decision suggested the lawyer incurs a return obligation from the moment the pre-payment is received, an alternative interpretation could be that a concrete claim for a specific monetary sum only crystallizes upon the completion of the mandate and final accounting. If so, at the time of an assignment order issued mid-mandate, one could argue the claim for a determinable sum doesn't yet "currently exist." However, the 2006 decision focused primarily on the indeterminacy of the amount.

Conclusion: Certainty is Key for Assignment Orders

The Supreme Court's April 14, 2006, decision underscores the importance of certainty and determinability in the context of assignment orders. By holding that a client's claim for the return of pre-paid expenses from a lawyer engaged in ongoing services lacks the requisite "face value" until those services are completed, the Court protected the integrity of the mandate relationship. It ensures that professionals can continue to utilize pre-paid funds for their intended purpose without the interference that a premature assignment order would cause, while also upholding the principle that an assignment order should only apply to claims whose value is sufficiently fixed at the time of issuance. This ruling provides important clarity for creditors, debtors, and professionals handling client funds for ongoing mandates.