The "Shellfish Gathering" Case: Calculating Lost Future Earnings When a Victim Dies from an Unrelated Cause

Date of Judgment: April 25, 1996

Case Name: Claim for Damages

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

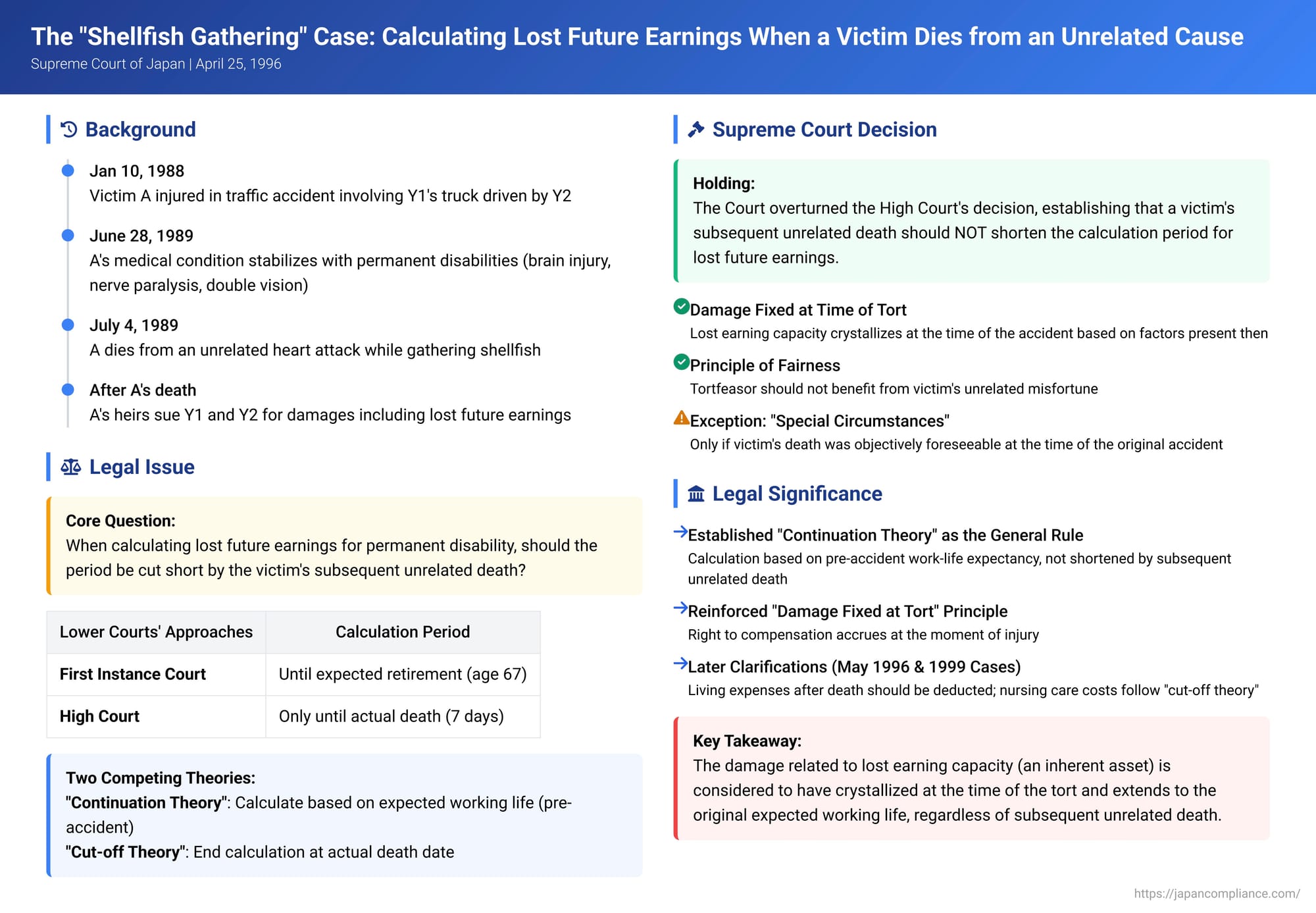

In personal injury law, one of the most significant components of a damages award is often "lost future earnings" (逸失利益 - isshitsu rieki) resulting from permanent disabilities that impair a victim's ability to work. Courts typically calculate this by estimating the victim's probable working lifespan and the extent of their diminished earning capacity. But what happens if the victim, after suffering a permanent disability from an accident, dies prematurely from a completely unrelated cause before the end of their initially projected working life? Should the calculation of their lost future earnings be cut short at the actual date of death, or should it still be based on their pre-accident life/work expectancy? This complex and poignant question was addressed by the Japanese Supreme Court in a notable 1996 decision, often referred to as the "Shellfish Gathering Case."

An Accident, a Disability, and an Unrelated Death: The Facts

The case involved a sequence of tragic events:

- The Traffic Accident and Injuries: On January 10, 1988, A was a passenger in a cargo vehicle driven by B. This vehicle collided with a large truck owned by Y1 and driven by Y2. A suffered severe injuries, including a brain contusion and skull fractures.

- Permanent Disability: After extensive medical treatment, A's condition stabilized on June 28, 1989, but he was left with permanent after-effects (後遺症 - kōishō). These included diminished intelligence, left peroneal nerve paralysis (affecting his lower leg and foot), and diplopia (double vision). At the time of the accident, A had been employed as a carpenter. Due to his disabilities, he was unable to return to work.

- The Subsequent, Unrelated Death: Unable to resume his carpentry work, A, as part of his rehabilitation and daily routine, would often go to the nearby sea to gather shellfish. Tragically, on July 4, 1989 (just a few days after his medical condition from the traffic accident had stabilized), while gathering shellfish in the sea, A suffered a heart attack and died.

- The Lawsuit and Claims: A's heirs (X et al.) sued Y1 (the truck owner) and Y2 (the truck driver) for damages resulting from the traffic accident. Their claims included:

- Medical expenses, lost wages during A's treatment, and solatium (慰謝料 - isharyō, for pain and suffering related to the injuries and hospitalization).

- Primary Claim: Lost future earnings and solatium based on A's death, arguing there was an adequate causal link between the traffic accident and his eventual death (this was denied by the lower courts and was not the main focus of the Supreme Court appeal).

- Alternative Claim (Central to the Appeal): Lost future earnings due to A's permanent disabilities (後遺障害逸失利益 - kōishō isshitsu rieki) from the date his condition stabilized (June 28, 1989) until his presumed retirement age of 67, as well as solatium for these permanent disabilities.

- Lower Court Rulings on Lost Future Earnings Due to Disability:

- The first instance court found no adequate causal link between the traffic accident and A's death from the heart attack. However, it did recognize A's claim for lost future earnings due to the permanent disabilities caused by the traffic accident. It calculated these lost earnings based on A's projected working lifespan up to age 67, making a 30% deduction for living expenses (a standard deduction if the claim was for death-related lost earnings, though arguably misapplied here for disability-related lost earnings where the victim is still alive and incurring those expenses). This resulted in an award of over ¥9.43 million for lost future earnings.

- The High Court also denied a causal link between the accident and the death. Crucially, regarding the lost future earnings due to disability, it took a different stance. It reasoned that because A had died from an unrelated cause before the conclusion of the trial's oral arguments, his actual period of lost earnings due to the disability was fixed and known. The High Court held that in such a situation, where the victim's actual lifespan post-stabilization is determined by an unrelated death before judgment, this fact must be taken into account. Therefore, it only awarded lost future earnings for the very short period between A's medical stabilization (June 28) and his death while gathering shellfish (July 4) – a mere seven days, amounting to only ¥26,800. It denied any claim for lost earnings for the period after A's actual death.

X et al. (A's heirs) appealed this drastically reduced award for lost future earnings to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Focusing on the Time of the Tort

The Supreme Court, on April 25, 1996, overturned the High Court's decision regarding the calculation of lost future earnings due to disability. It held that A's subsequent death from an unrelated cause should not be used to shorten the period for which lost future earnings (due to the permanent disabilities from the traffic accident) are calculated.

The Core Principle:

The Court articulated the following key principle:

- "When a victim of a traffic accident loses a part of their physical functionality and, as a result, suffers a partial loss of earning capacity due to injuries caused by that accident, in calculating the so-called lost future earnings, even if the victim subsequently dies, the fact of that death should not be considered in determining the potential working period, unless special circumstances exist."

- Such "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) would only apply if, at the time of the original traffic accident, there was a concrete, existing cause for the victim's death (other than the accident injuries themselves), and their death in the near future was objectively foreseeable at that point.

Rationale for the Rule:

The Supreme Court provided two main reasons for this "continuation theory" (as opposed to the High Court's "cut-off theory"):

- Damage Crystallizes at the Time of the Tort: The damage resulting from the loss of earning capacity due to the accident-induced permanent disability occurs and is fixed in its nature and extent at the time of the traffic accident itself. Subsequent events (like an unrelated death) do not alter the nature or extent of that specific damage which had already vested. The amount of lost future earnings should be calculated based on factors present at the time of the accident: the victim's age, occupation, health status (pre-accident), and statistical data on average working lifespans and life expectancy. The victim's later death from an unrelated cause is not a factor to be considered in assessing the duration of the earning capacity lost due to the accident, unless that death was already an objectively predictable event at the time of the accident.

- Considerations of Fairness (衡平の理念 - kōhei no rinen): It would be contrary to the principle of fairness if a tortfeasor who caused a permanent loss of earning capacity could have their liability reduced or extinguished simply because the victim later died from an unrelated, fortuitous event. Conversely, it would be unfair if the victim (or their heirs) were unable to receive full compensation for the earning capacity lost due to the tortfeasor's actions, just because of an intervening, unrelated death.

Application to the Case:

In A's case, the Supreme Court found:

- A suffered a partial loss of earning capacity due to the permanent disabilities caused by the traffic accident.

- There was no evidence that, at the time of the traffic accident, A had any pre-existing condition or other specific circumstance that made his subsequent death from a heart attack while gathering shellfish objectively foreseeable.

- Therefore, A's lost future earnings due to his disability should be calculated based on his full expected working lifespan (up to age 67), without being cut short by his unrelated death.

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's calculation and remanded the case for a recalculation of damages consistent with this principle.

Implications of the "Shellfish Gathering Case"

This 1996 Supreme Court decision, often referred to as the "Shellfish Gathering Case" (貝採り事件 - kai-tori jiken), is a significant ruling in Japanese tort law concerning the assessment of damages for lost future earnings.

- Adoption of the "Continuation Theory": The judgment clearly established the "continuation theory" as the general rule for calculating lost future earnings due to permanent disability: the calculation period is based on the victim's pre-accident work-life expectancy and is not shortened by a subsequent unrelated death, unless that death was objectively foreseeable at the time of the tort.

- Reinforcing the "Damage Fixed at Tort" Principle: It reinforces the legal concept that the compensable damage for lost earning capacity crystallizes at the moment the tort occurs. The full extent of that lost capacity, projected over a normal working life, is the damage, and subsequent unrelated events don't diminish this already-accrued right to compensation.

- Fairness as a Guiding Principle: The Court's reliance on the "principle of fairness" is notable. It prevents a windfall for the tortfeasor and ensures that the victim's estate is compensated for the full economic impact of the disability that the victim would have had to endure for their expected working life had they not died from an unrelated cause.

- Clarification after Subsequent Rulings:

- Almost immediately after this judgment, another Supreme Court decision (May 31, 1996) reaffirmed this "continuation theory" principle broadly, stating it applies regardless of the cause of the subsequent death (illness, accident, suicide, natural disaster) and regardless of whether another party might be liable for that death, or whether there was any causal link (even indirect) between the original tort and the subsequent death.

- However, that same May 1996 decision introduced a crucial caveat regarding deductions for living expenses. It held that if the victim dies and the claim is for damages due to death (which inherently includes future lost earnings), then living expenses that the deceased would have incurred are deducted. The Court clarified that if lost future earnings for disability are claimed, and the victim subsequently dies from an unrelated cause, living expenses for the period after death should also be deducted from the disability-based lost earnings award. This is because the heirs are essentially claiming a stream of income the deceased would have earned and partly used for themselves; if the deceased is no longer alive to incur those expenses, the heirs should not receive that portion.

- Later, in a 1999 Supreme Court case concerning future nursing care costs for a tort victim who subsequently died from an unrelated cause before trial conclusion, the Court adopted a "cut-off theory." It ruled that the need for nursing care ceases upon death, and therefore, compensation for future nursing care costs is limited to the actual period the victim was alive and needed care. This was distinguished from lost earning capacity, with the Court emphasizing that nursing care costs are actual, out-of-pocket expenses whose necessity ends with death.

The "Shellfish Gathering Case" and the subsequent related rulings illustrate the judiciary's efforts to develop coherent and fair principles for calculating damages in complex personal injury scenarios, balancing the need for full compensation with the prevention of unjust enrichment.

Conclusion

The 1996 "Shellfish Gathering Case" is a vital precedent in Japanese personal injury law. It establishes that when calculating lost future earnings due to a permanent disability caused by a tort, the victim's subsequent death from an entirely unrelated and unforeseeable cause does not shorten the period for which those earnings are assessed. The damage related to lost earning capacity is considered to have crystallized at the time of the tortious injury, based on the victim's pre-accident work-life expectancy. This principle, guided by fairness, ensures that tortfeasors do not receive an unmerited reduction in their liability due to a later, unrelated misfortune suffered by the victim, thereby aiming for a more complete compensation for the harm originally inflicted. However, the practical calculation, particularly regarding deductions for living expenses after an unrelated death, has been further refined by subsequent case law.