The Server is Overseas, But the Crime is in Japan: A Landmark Ruling on Cyber-Pornography

The borderless nature of the internet poses a profound challenge to legal systems built on territorial jurisdiction. If a website hosted on a server in the United States provides illegal content to a user in Japan, where does the crime occur? Who is the responsible party—the operator who set up the site, or the end-user who clicks the "download" button? And which country has the right to prosecute?

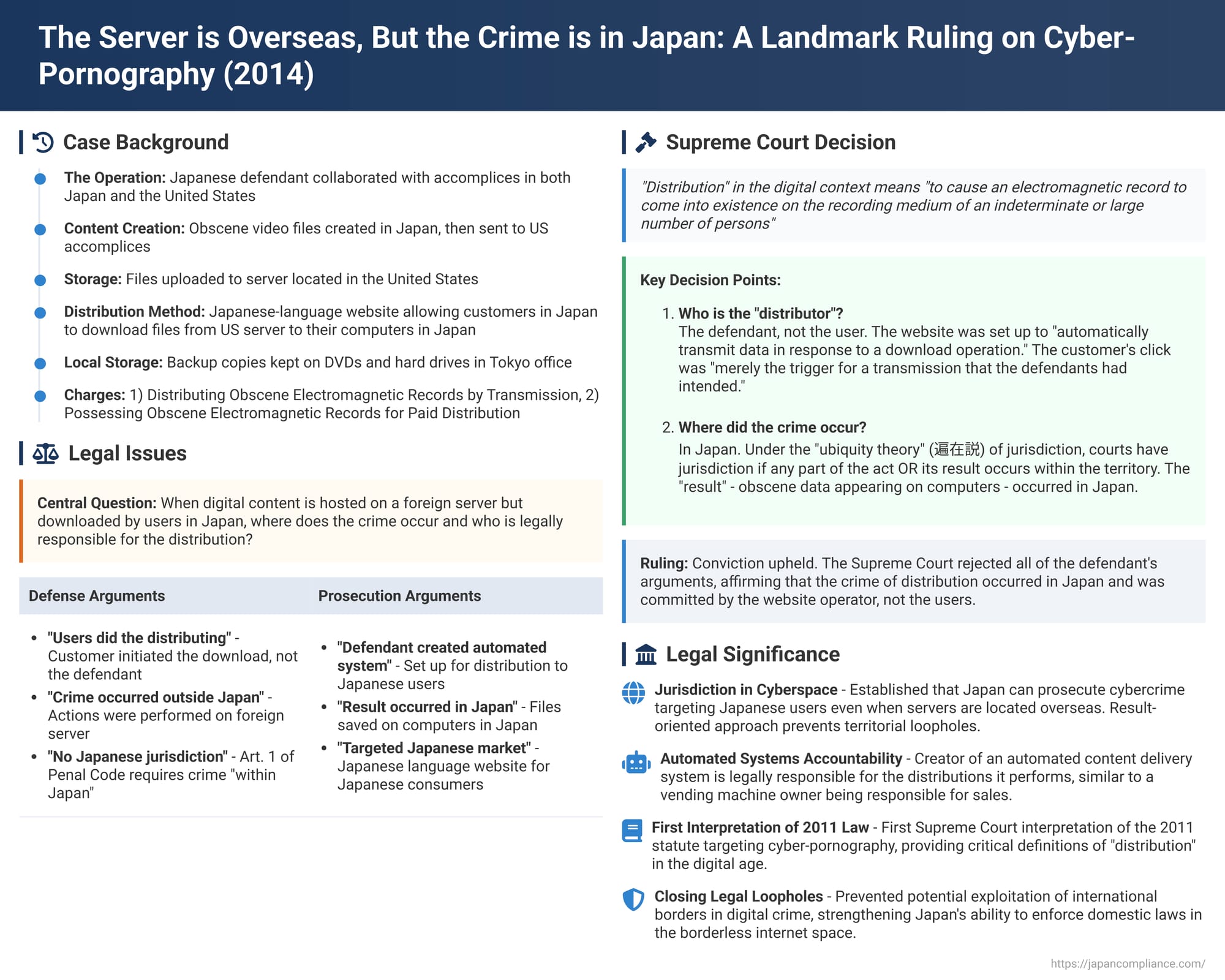

These critical questions of the digital age were at the center of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 25, 2014. The case was the Court's first opportunity to interpret a then-new statute designed to combat the online distribution of obscene material. The ruling provided crucial answers, establishing how Japanese law applies to cross-border cybercrime and defining who is legally responsible for automated online content delivery.

The Facts: A Cross-Pacific Obscenity Business

The case involved an international conspiracy to sell obscene videos to a Japanese clientele.

- The Operation: The defendant, residing in Japan, worked with accomplices in both Japan and the United States.

- The Workflow: The group would create obscene video data files within Japan. These files were then sent to the accomplices in the U.S., who uploaded and stored them on a server computer located within the United States.

- The Website: They operated a Japanese-language website designed to sell these videos to an indeterminate and large number of customers, who were primarily Japanese.

- The Distribution Method: Customers in Japan would access the website, pay a fee, and then, through their own online operations, download the data files. The files would be sent from the U.S. server and saved onto the customers' personal computers located within Japan.

- The Backup Copies: In addition to the online operation, the defendant also kept backup copies of the obscene video data on DVDs and hard drives in an office in Tokyo for the purpose of this paid distribution scheme.

The defendant was charged with two crimes: (1) Distributing Obscene Electromagnetic Records by Transmission for the customer downloads, and (2) Possessing Obscene Electromagnetic Records for the Purpose of Paid Distribution for the backups in Tokyo.

The Defense's Digital-Age Argument

The defendant's defense was built on the complexities of internet architecture and international law.

- "I Didn't Distribute, the User Did": He argued that he was not the one who performed the act of "distribution" (hanpu). The data transfer from the U.S. server to the Japanese computer only occurred because of the customer's own action of initiating the download.

- "The Crime Happened Outside Japan": He claimed his only actions—setting up and operating the website—were conducted on a foreign server. Therefore, he argued, he had not "committed a crime within Japan" as required by Article 1 of the Penal Code for Japanese jurisdiction to apply.

- The Knock-on Effect: If the distribution charge failed due to a lack of jurisdiction, he argued the possession charge must also fail. The possession of backups in Tokyo would lack the required criminal purpose, as the purpose was for an overseas distribution that was not a crime in Japan.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Defining Crime in Cyberspace

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's arguments on all points and upheld the convictions. In doing so, it provided the first authoritative interpretation of the 2011 law targeting "cyber-pornography."

Part 1: Who is the "Distributor"?

The Court first had to define "distribution" (hanpu) in the digital context and determine who was the actor.

- Definition of Digital "Distribution": The Court defined the term as "to cause an electromagnetic record... to come into existence on the recording medium of an indeterminate or large number of persons." This definition, consistent with the legislative intent behind the 2011 law, focuses on the end result: the recipient obtaining a saved copy of the data.

- The Actor in an Automated System: The Court decisively rejected the argument that the customer was the one performing the act. It reasoned that the website was set up with a function to "automatically transmit data in response to a download operation." The customer's click was "merely the trigger for a transmission that the defendants had intended." Therefore, the Court concluded, it was the defendants who "transmitted the data from the server computer to the customer's personal computer." This act of causing the data to be saved on the customer's device is "distribution."

Part 2: Where did the Crime Occur?

Having established that the defendant's conduct was "distribution," the Court then turned to the question of jurisdiction.

- A Domestic Crime: The Court stated briefly but definitively that under the facts of the case, it was "clear" that the defendants had committed the crime "within Japan."

- The "Ubiquity Theory" of Jurisdiction: While the Court did not elaborate, its conclusion is based on a long-standing principle of Japanese criminal law known as the "ubiquity theory" (henzai-setsu). Under this theory, a court has jurisdiction if any part of the criminal act or its result occurs within its territory.

- The Result in Japan: In this case, the criminal "result"—as defined by the Court, the obscene data coming into existence on a recording medium—occurred on the customers' personal computers. Since these computers were located in Japan, the result of the crime took place in Japan, firmly establishing the jurisdiction of Japanese courts.

Analysis: Closing the Loopholes of the Internet Age

This 2014 decision was a crucial step in adapting Japanese criminal law to the challenges of the internet.

- The Vending Machine Analogy: The Court's logic on who the "distributor" is can be easily understood through an analogy to a vending machine. The person who stocks and maintains an automated vending machine is the one engaged in the act of selling, even though the final transaction is triggered by a customer inserting money and pressing a button. Similarly, the defendant, by creating and operating an automated website designed for distribution, was legally responsible for the distributions that system carried out.

- Jurisdiction in a Borderless World: The jurisdictional finding is equally significant. By focusing on the location of the result of the crime, the Court affirmed Japan's sovereign power to prosecute cross-border digital offenses that harm or target its society. This prevents a scenario where an operator could deliberately target a country's population from an overseas server and claim immunity from that country's laws. The fact that the website was in Japanese and marketed to Japanese customers further strengthened the connection to Japan, a factor that could be important in future, more complex cross-border cases.

- Relationship to "Public Display": It is worth noting that the defendant's actions could also have been prosecuted under a different legal theory: "Publicly Displaying an Obscene Electromagnetic Recording Medium." A 2001 Supreme Court decision had already established that making obscene data available for download on a server constitutes a "public display" of the server's hard disk. However, in a cross-border case like this one, prosecuting the "display" that occurs on a foreign server raises more complex jurisdictional questions. The new "transmission distribution" charge, which focuses on the result occurring in Japan, offered a more straightforward path to establishing jurisdiction.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2014 ruling provided robust and essential interpretations of Japan's new cyber-obscenity laws, closing potential loopholes that could be exploited by cross-border criminal enterprises. The decision established two clear principles for the digital age: first, an operator who creates an automated system for content delivery is the legal "distributor" of that content, and second, a digital crime whose illegal result materializes within Japan is a "domestic crime" subject to Japanese law, regardless of where the server is located. The case stands as a powerful example of how legal systems can adapt to technological change, ensuring that territorial borders do not become shields for illegal online activities that target a country's population.