The Sealed Envelope: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Holographic Will Formalities

Date of Judgment: June 24, 1994 (Heisei 6)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Heisei 6 (o) No. 83 (Appeal Against Judgment Concerning Claim for Confirmation of Will Invalidity)

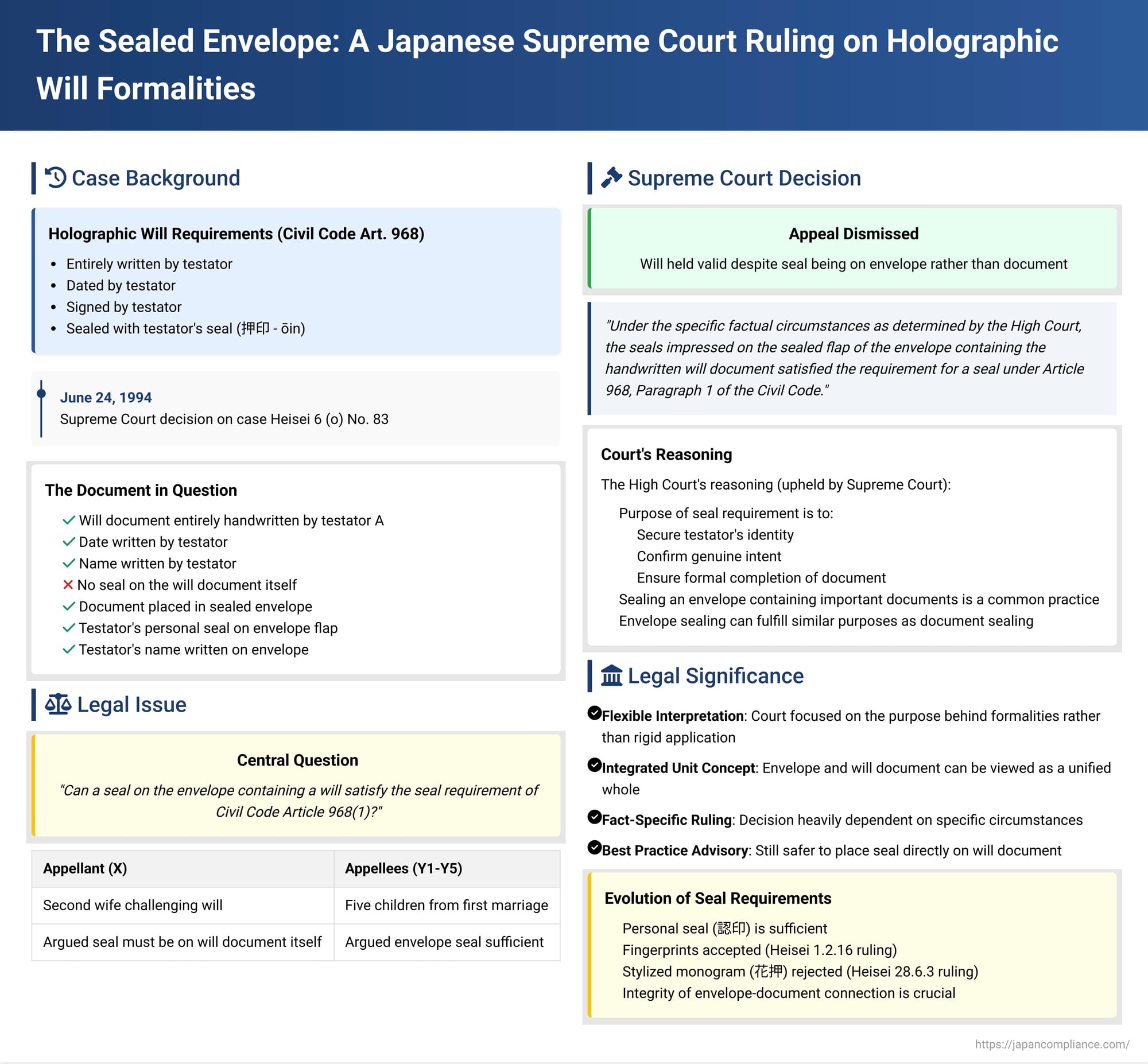

Holographic wills (自筆証書遺言 - jihitsu shōsho igon), entirely handwritten by the testator, are a common method of estate planning in Japan. However, they are subject to strict formal requirements under Article 968, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code to ensure their authenticity and the testator's true intent. These requirements include that the will be entirely written, dated, and signed by the testator, and that it bear the testator's seal (押印 - ōin). A crucial question arose in a 1994 Supreme Court case: what if the testator's seal is not on the will document itself, but rather on the sealed flap of the envelope containing the will? Does this satisfy the statutory requirement?

Facts of the Case: A Will Sealed, But Not Directly on the Document

The case involved the holographic will of the deceased, A.

- The Testator and the Will Document: A had prepared a holographic will (the "Will Document"). It was undisputed that the entire text of the will, the date, and A's name written on the Will Document were all in A's own handwriting.

- The Missing Seal on the Document: However, A's personal seal was not impressed directly on the Will Document itself, for example, under or next to his handwritten name as is customary.

- The Sealed Envelope: The Will Document had been placed inside an envelope (the "Will Envelope"). This envelope was sealed. A's personal seal, bearing his surname, was found impressed in two places on the sealed flap of this Will Envelope. Additionally, A's full name was handwritten on the back of the Will Envelope.

- The Parties to the Dispute:

- X (Haruko K. in the judgment, the plaintiff/appellant) was A's second wife. She challenged the validity of the will.

- Y1 through Y5 (Natsuko O. et al. in the judgment, the defendants/appellees) were A's five children from his first marriage. They sought to have the will upheld as valid.

- The Legal Challenge: X filed a lawsuit against Y1-Y5, seeking a court declaration that A's will was invalid. The primary basis for this claim was that the Will Document itself lacked A's seal, which X argued was a fatal defect under the formal requirements of Article 968, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code.

- Lower Court Rulings Upholding the Will:

- First Instance Court: This court dismissed X's claim and found the will to be valid. It reasoned that while the manner of sealing was somewhat different from the typical practice of sealing directly under the signature on the document, the method used in this case did not fall short in ensuring the testator's identity, their genuine intent, and the sense of completeness and finality of the will.

- High Court (Original Appeal): The High Court also dismissed X's appeal, affirming the will's validity. The High Court elaborated on the purpose of the seal requirement under Article 968(1): it is intended, in conjunction with the handwritten text, date, and signature, to (a) secure the testator's identity and confirm their genuine intent, and (b) ensure the formal completion of the document, reflecting a long-standing Japanese legal custom and consciousness for important documents to be finalized with a seal after signing. The High Court found that impressing a seal on the flap of a sealed envelope containing an important document, such as a will, is not an uncommon practice and serves similar purposes: it helps identify the sender/originator, confirms their intent regarding the contents, and marks the enclosed document as finalized and complete. Given that A's will was in a letter-like format, the court likely considered the act of placing it in a sealed and stamped envelope as an integral part of the testamentary act. Therefore, the High Court concluded that the seals on the Will Envelope, under these circumstances, did not undermine the legislative intent behind the seal requirement in Article 968(1).

- X's Appeal to the Supreme Court: X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court. She argued that the High Court's interpretation undervalued the significance of the testator's conscious and deliberate act of creating a legally effective document by both signing and sealing the will document itself. X also contended that a seal on an envelope flap typically serves merely to indicate a desire to prevent unauthorized opening, rather than to formally validate the contents as a will.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Seal on Envelope Can Suffice

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal.

The Court, affirming the High Court's judgment, held that:

Under the specific factual circumstances as determined by the High Court, the seals impressed on the sealed flap of the envelope containing the handwritten will document satisfied the requirement for a seal under Article 968, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code. There was no deficiency in meeting this "seal" requirement.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1994 Supreme Court decision is an important clarification regarding the formal requirements for holographic wills, particularly the seal requirement.

- Purpose of the Seal Requirement: The PDF commentary accompanying this case references an earlier Supreme Court decision (Heisei 1.2.16 - February 16, 1989) which articulated the dual purpose of the seal requirement in Article 968(1):

- To work in conjunction with the handwritten text, date, and signature to help secure the testator's identity and confirm their genuine intent regarding the disposition of their property.

- To ensure the formal completion and finality of the will document, reflecting a deep-rooted Japanese legal custom and consciousness where important documents are signed and then a seal is impressed, often beneath or near the signature, to signify finalization.

- Flexibility in Seal Placement – Context is Key: The 1994 judgment demonstrates that the courts may allow a degree of flexibility regarding the precise location of the seal, provided the fundamental purposes of the seal requirement (identity, intent, and completion) are deemed satisfied within the overall context of the will's creation and preservation. The High Court, whose reasoning was effectively endorsed by the Supreme Court, had emphasized that as long as the legislative intent behind requiring a seal is not undermined, the seal does not absolutely and in all circumstances have to be placed directly under the signature on the will document itself.

- The "Envelope and Will as an Integrated Unit" Concept (Implied): While the Supreme Court's judgment was concise and directly affirmed the High Court's conclusion based on the established facts, the overall acceptance of the High Court's reasoning implies a recognition that, in certain situations, the envelope and the act of sealing it can be viewed as an integral part of the execution of the holographic will. This is particularly plausible when the will is in a letter format, and the sealing of the envelope serves to finalize and secure the testamentary document within. The PDF commentary suggests that the Supreme Court likely proceeded on the premise that the Will Envelope, in this instance, formed part of the overall testamentary act.

- Distinctions from Other Seal-Related Cases:

- Exceptional Circumstances for No Seal: The PDF commentary references a Supreme Court case from Showa 49 (1974) where a holographic will written in English by a naturalized Russian émigré, which had a signature but no seal, was upheld. However, this was deemed a highly exceptional case based on the testator's specific background, lifestyle, language use, and lack of customary use of seals in their personal and business dealings. It did not establish a general waiver of the seal requirement for most testators in Japan.

- Types of Seals: It is generally accepted that an ordinary personal seal (認印 - mitomein) is sufficient for a holographic will; a formally registered seal (実印 - jitsuin) is not mandatory. The Supreme Court has also accepted fingerprints (拇印 - boin, specifically a thumbprint) as satisfying the seal requirement (Heisei 1.2.16). However, it has ruled that a kaō (a stylized, handwritten monogram or mark used historically in place of a signature or seal) does not meet the modern requirement for a "seal" under Article 968(1) (Heisei 28.6.3 - June 3, 2016). The present 1994 case involved a standard personal seal, but its placement was the issue.

- Cautionary Note – Risks of Fraud and the Importance of Integrity: The PDF commentary acknowledges that legal scholars have raised valid concerns regarding the potential for fraud, substitution, or alteration if essential elements of a will, such as the date or the seal, are found only on an envelope rather than on the will document itself. The integrity of the sealed envelope—for instance, whether it was found intact and properly sealed at the time of probate (the court process for validating a will)—is likely a crucial factual element in such cases. The commentary points to a later Tokyo High Court decision (Heisei 18.10.25 - October 25, 2006) which invalidated a purported will where the document inside an envelope lacked the testator's signature and seal, and the envelope (which did bear a signature and seal) was found to have already been opened at the time of probate. In that instance, the court could not find that the document and the envelope had been created and maintained as an integrated and secure testamentary unit.

- Fact-Specific Nature of the Ruling: It is important to view the 1994 Supreme Court decision as heavily dependent on its specific facts. The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's judgment "under the factual circumstances as determined by the High Court." This suggests that the ruling does not create a blanket approval for any seal found on an envelope to automatically validate a will. Rather, it indicates that such a placement can be deemed sufficient if the overall context robustly supports the conclusion that the testator's identity is clear, their intent is genuine, and the act of sealing the envelope was intended to finalize the will document contained within.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1994 decision in this case offers an important illustration of how Japanese courts may interpret the strict formal requirements for holographic wills. While the general rule and safest practice remain for the testator to sign and affix their seal directly onto the will document itself, this judgment shows that a seal placed on the sealed envelope containing the will may satisfy the statutory requirements, provided that doing so, in the specific circumstances of the case, still fulfills the underlying legislative purposes of ensuring the testator's identity, their genuine intent, and the formal completion of the testamentary act. This ruling underscores a judicial willingness to uphold a testator's clear intent when formal requirements are met in substance, even if in a slightly unconventional manner, but it also implicitly highlights the importance of careful will execution and preservation to avoid such disputes.