The Scope of Wage Cuts During Strikes: A Deep Dive into Japan's Supreme Court Stance on Family Allowance (September 18, 1981)

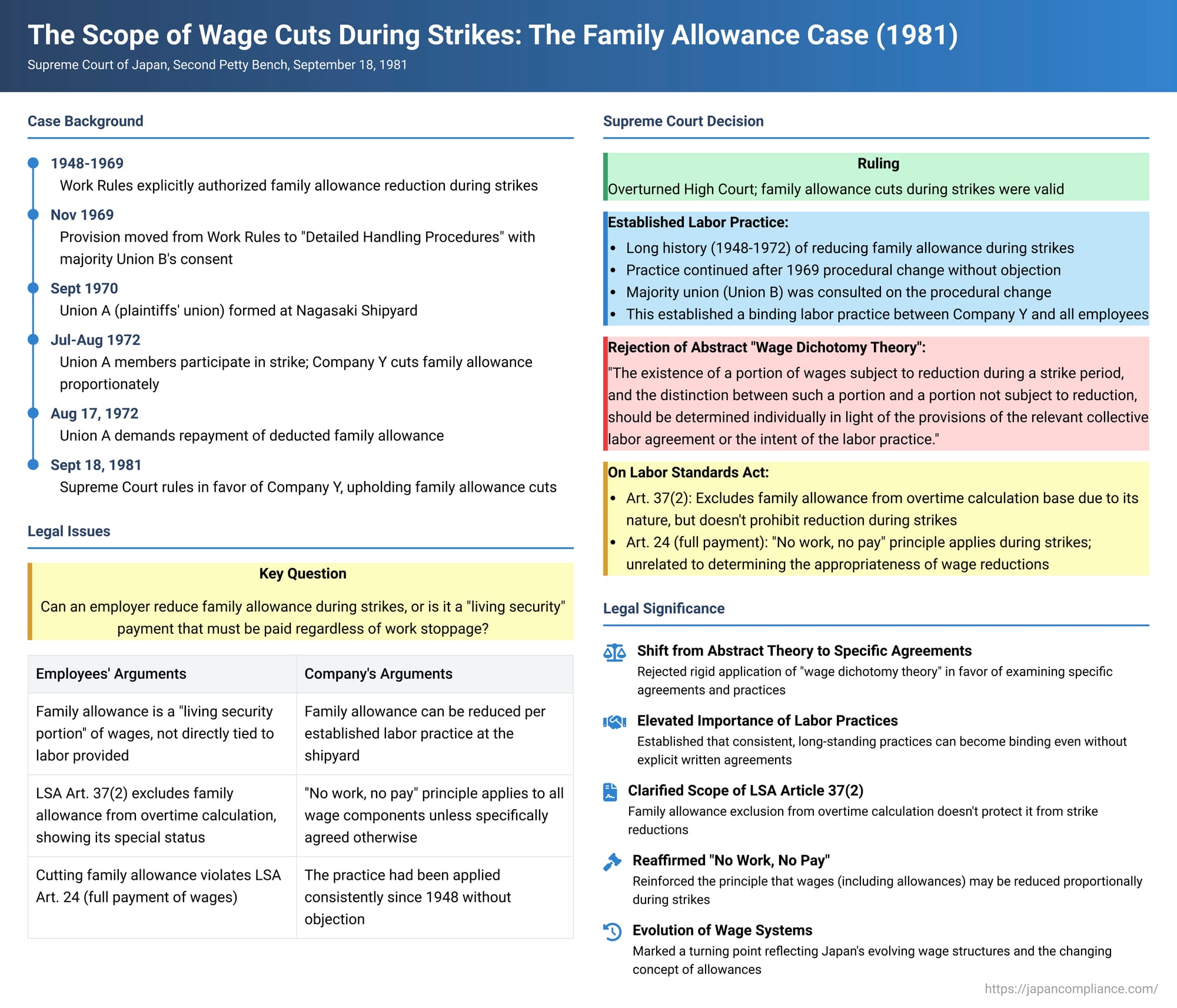

On September 18, 1981, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a pivotal judgment in a wage claim case that significantly shaped the understanding of how wages, particularly allowances like family allowance, can be treated during employee strikes. This case, involving Company Y and its employees, members of Union A, delves into the intricacies of labor practices, the interpretation of the Labor Standards Act (LSA), and the then-prevalent "wage dichotomy theory."

Case Reference: 1976 (O) No. 1273 (Wage Claim Case)

Appellant (Original Defendant): Company Y (represented by K. Kimura and eight others)

Appellees (Original Plaintiffs): Selected parties T. Kubota and two others (representing members of Union A) (represented by H. Yamamoto and one other)

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The original judgment (High Court) is overturned, and the judgment of the first instance (District Court) is reversed. The claims of the appellees are all dismissed. All court costs shall be borne by the appellees.

Factual Background: The Dispute Over Family Allowance

The core of the dispute lay in Company Y's decision to withhold family allowance payments to its employees, members of Union A at the Nagasaki Shipyard, for the periods they participated in strikes during July and August 1972.

The facts, as lawfully established by the High Court and reviewed by the Supreme Court, were as follows:

- The appellees (hereinafter "Mr. X et al.") were employees of Company Y working at its Nagasaki Shipyard and were members of Union A (the Nagasaki Shipyard Labor Union, formed on September 13, 1970).

- Following strikes conducted by Union A in July and August 1972, Company Y did not pay Mr. X et al. the family allowance corresponding to the strike periods on the scheduled paydays (the 20th of each month) and instead reduced their wages by these amounts.

- This family allowance was paid monthly based on the number of dependents, as stipulated by Article 18 of Company Y's Employee Wage Regulations (revised June 1972), which formed part of the company's Work Rules.

- At the Nagasaki Shipyard, from around 1948 until November 1969, a provision existed within the Employee Wage Regulations (part of the Work Rules) stipulating that hourly wages, including family allowance, would be reduced corresponding to the duration of any strike. Reductions in family allowance during strikes were made based on this provision.

- On November 1, 1969, Company Y removed the specific provision regarding family allowance reduction from the main Wage Regulations. Around the same time, it established similar provisions within new "Detailed Handling Procedures" for the Employee Wage Regulations. In creating these Detailed Handling Procedures, Company Y apparently obtained the consent of Union B (the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Labor Union), which was organized by a majority of Company Y's employees. (Union A, to which Mr. X et al. belonged, was formed later in September 1970 and did not exist at the time these Detailed Handling Procedures were created).

- Even after this revision, Company Y continued to reduce family allowance during strikes as before, until the family allowance system was abolished and a dependent allowance was newly established in 1974.

- On August 17, 1972, Union A requested Company Y to repay the deducted family allowance amounts.

The Journey Through the Lower Courts

The District Court found in favor of the employees (Mr. X et al.). It distinguished wages into an "exchange part," considered direct compensation for labor provided, and a "living supplementary/security part," such as family allowance. The District Court reasoned that the Labor Standards Act, particularly Article 37 (which excludes family allowance from the calculation base for overtime pay), suggests that family allowance should not be subject to wage cuts during strikes unless there's a specific collective agreement or a consensus based on labor-management practices. The court found no such agreement or effective established practice in this case, deeming the cuts invalid.

The High Court also ruled in favor of Mr. X et al., upholding the District Court's decision but with slightly different reasoning. It determined that the "Detailed Handling Procedures," where the family allowance cut provision was moved, could not be recognized as part of the official Work Rules. Furthermore, there was no agreement with Union A (the plaintiffs' union) regarding these cuts. The High Court also found the practice of cutting family allowance to be "markedly unreasonable" and thus could not be recognized as a de facto custom. Consequently, it held that the cuts violated Article 24 of the Labor Standards Act, which mandates the full payment of wages.

The High Court specifically stated that it could not recognize the reduction of family allowance as an established labor practice that had become part of the employment contracts with Mr. X et al. It viewed cutting family allowance in this instance as "markedly unreasonable" in light of the purpose of Article 37, Paragraph 2 of the LSA and Article 25 of the company's own wage regulations. Such an unreasonable working condition, even if unilaterally continued by the company, could not be affirmed as a lawful and valid de facto practice.

Company Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and dismissed the employees' claims. Its reasoning was multifaceted:

1. Establishment of a Labor Practice (労働慣行 - Rōdō Kankō)

Contrary to the High Court, the Supreme Court inferred the existence of an established labor practice regarding the reduction of family allowance during strikes between Company Y and Union A. The Court based this inference on several factors:

- The practice of reducing family allowance during strikes had been implemented based on the Work Rules (Wage Regulations) from approximately 1948 until October 1969.

- Even after the provision was removed from the main Wage Regulations in November 1969 and incorporated into the "Detailed Handling Procedures," the company had sought the opinion of Union B, the majority union representing Company Y's employees.

- This same practice of reduction continued thereafter without objection until 1974 (when the allowance system changed).

The Supreme Court concluded that given this history, it was reasonable to infer that the reduction of family allowance during strikes had become an established labor practice binding on both Company Y and the members of Union A.

2. Reasonableness of the Labor Practice

The Supreme Court then addressed the High Court's finding that such a practice was "markedly unreasonable." The Supreme Court disagreed. It stated that this labor practice could not be deemed grossly unreasonable, particularly when considered in light of:

- Article 37, Paragraph 2 of the Labor Standards Act, which stipulates that family allowance is not included in the base wage for calculating overtime pay.

- Article 25 of Company Y's own Wage Regulations, which mirrored this statutory exclusion.

The Court found that the High Court's decision to deem the family allowance reduction illegal, based on a differing view of reasonableness, was an error in the interpretation and application of laws and regulations, and this error clearly affected the outcome of the judgment.

3. Rejection of the Abstract "Wage Dichotomy Theory" (賃金二分論 - Chingin Nibunron)

Mr. X et al. argued that the family allowance constituted a "living security portion" of wages, distinct from the "exchange portion" (direct payment for labor), and therefore should not be subject to reduction even during a strike. This argument is based on the "wage dichotomy theory."

The Supreme Court rejected this line of argument as it was applied by the employees. It stated:

"The existence of a portion of wages subject to reduction during a strike period, and the distinction between such a portion and a portion not subject to reduction, should be determined individually in light of the provisions of the relevant collective labor agreement or the intent of the labor practice."

Since the Court had already found that a labor practice of reducing family allowance existed at Company Y's Nagasaki Shipyard even after November 1969, the employees' argument, premised on an abstract, general wage dichotomy theory, lacked its foundational premise and was therefore untenable. The Supreme Court also distinguished a precedent case cited by the employees (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench judgment, February 5, 1965, often known as the Meiji Life Insurance case) as being different in its factual circumstances and thus not applicable to the present case.

4. Interpretation of Labor Standards Act Articles 37(2) and 24

Mr. X et al. further contended that the reduction of family allowance violated:

(1) The legislative intent of Article 37, Paragraph 2 of the LSA (which excludes family allowance from the overtime pay calculation base).

(2) The provisions of Article 24 of the LSA (the principle of full payment of wages).

The Supreme Court dismissed these arguments as well:

- Regarding LSA Article 37, Paragraph 2: The Court explained that the reason this article excludes family allowance from the overtime pay calculation base is because family allowance is a wage component paid based on the worker's personal circumstances. Including it as a general rule in the overtime calculation base could lead to inappropriate outcomes. The Court clarified that just because family allowance has a weaker direct link to work performed, this does not inherently mean that reducing it during a strike is immediately illegal. The provision is about overtime calculation, not about the permissibility of wage cuts during strikes per se.

- Regarding LSA Article 24: The Court stated that the principle of full payment of wages prescribed in Article 24 is unrelated to determining the appropriateness of wage reductions accompanying a strike. This aligns with the widely accepted "no work, no pay" principle, which holds that if no work is performed (as during a strike), the corresponding wages are not due.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Company Y's reduction of the family allowance was not illegal or invalid. The claims of Mr. X et al. were unfounded and dismissed.

Analysis and Significance of the Ruling

This 1981 Supreme Court decision, often referred to as the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagasaki Shipyard case, carries substantial weight in Japanese labor law concerning wage cuts during industrial disputes.

- Shift from Wage Dichotomy Theory:

The most significant impact of this judgment was its clear move away from a rigid application of the "wage dichotomy theory". This theory, previously influential, differentiated wages into two parts:- An "exchange part" (e.g., basic salary), directly given in return for labor, which could be reduced under the "no work, no pay" principle during a strike.

- A "living security/supplementary part" (e.g., family allowance, housing allowance), seen as supporting the employee's livelihood based on their status as an employee rather than direct labor input, which was argued to be less susceptible or not susceptible to cuts.

The Meiji Life Insurance case (1965) was often cited in support of this theory, suggesting that allowances with a clear "living aid" nature couldn't automatically be cut.

This 1981 Supreme Court ruling, however, explicitly stated that the scope of wage cuts should be determined "individually in light of the provisions of the relevant collective labor agreement or the intent of the labor practice," rather than by a blanket application of the wage dichotomy theory. This signaled a preference for a more concrete, case-by-case analysis based on actual agreements and established practices within the specific workplace.

- Emphasis on Labor Practices (Rōdō Kankō):

The judgment underscores the critical role of established labor practices in determining terms and conditions of employment, including the treatment of wages during strikes. The Court's willingness to infer a binding labor practice based on a long history of consistent application, even after a formal rule was moved from the main Work Rules to supplementary regulations, and with the involvement of a majority union (even if not the plaintiff union), is noteworthy.

This highlights for employers and unions the importance of clearly documenting and consistently applying workplace rules and practices. It also raises questions, as noted in some academic commentary, about the conditions under which a practice involving one union (especially a majority union) can be deemed to bind members of another, minority union, particularly if the latter did not exist at the time of the practice's formalization in a new document. The Court seemed to infer the practice was between the company and the employees represented by Union A, likely through the continuation of an undisputed practice at the shipyard. - Interpretation of LSA Article 37, Paragraph 2:

The ruling clarified that Article 37, Paragraph 2 of the LSA, by excluding family allowance from the overtime calculation base, does not inherently shield this allowance from wage cuts during strikes. The Court viewed the purpose of this LSA provision as preventing inappropriate inflation of overtime pay due to factors (like family size) unrelated to the intensity or duration of extra work. It did not interpret this as a broader statement that family allowance is so disconnected from labor that it cannot be part of a wage reduction scheme agreed upon or established by practice. - Affirmation of "No Work, No Pay":

The Court's dismissal of the argument based on LSA Article 24 (full payment of wages) reinforces the "no work, no pay" principle as the general starting point for wage entitlement during strikes. The question then becomes which components of the total wage package are considered "payment for work" that was not performed. This ruling indicates that even allowances not directly tied to hourly performance can be subject to reduction if agreements or practices allow. - Evolution of Wage Systems and Future Relevance:

Commentators have noted that this case might have marked a turning point reflecting evolving wage structures in Japan. As traditional, seniority-based wage systems with numerous allowances give way to more performance-oriented or role-based pay, the conceptual underpinnings of the wage dichotomy theory may become less relevant. However, the principle of looking to specific agreements and established practices to determine the scope of wage cuts remains a crucial takeaway. Even as employment and wage forms continue to change, the case serves as a reminder to analyze the contractual basis for wage components and how they are treated under various circumstances, including industrial action.

Conclusion

The 1981 Supreme Court decision in the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagasaki Shipyard case established that the permissibility of cutting specific wage components like family allowance during a strike hinges not on an abstract classification of the wage type (as under the wage dichotomy theory) but on the concrete terms of collective labor agreements or established, consistently applied labor practices within the enterprise. The Court affirmed that a long-standing, recognized practice of reducing family allowance, supported by its historical inclusion in employment regulations and consultation with a majority union, was not grossly unreasonable and could form a valid basis for such reductions. This ruling emphasizes a pragmatic, individualized approach to resolving disputes over wage cuts during strikes, placing significant weight on the actual, developed norms and agreements within a given workplace.