The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

It's a classic trope of crime fiction: to save the boss, a loyal underling agrees to "take the fall." This "scapegoat" (migawari) walks into a police station and confesses to a crime they did not commit, hoping to exonerate the real perpetrator who is already in jail. But is this dramatic act of loyalty a crime in itself? Can you legally "aid the escape" of a criminal who is already securely behind bars? And if the police see through the ruse and the plan fails, has any crime actually been completed?

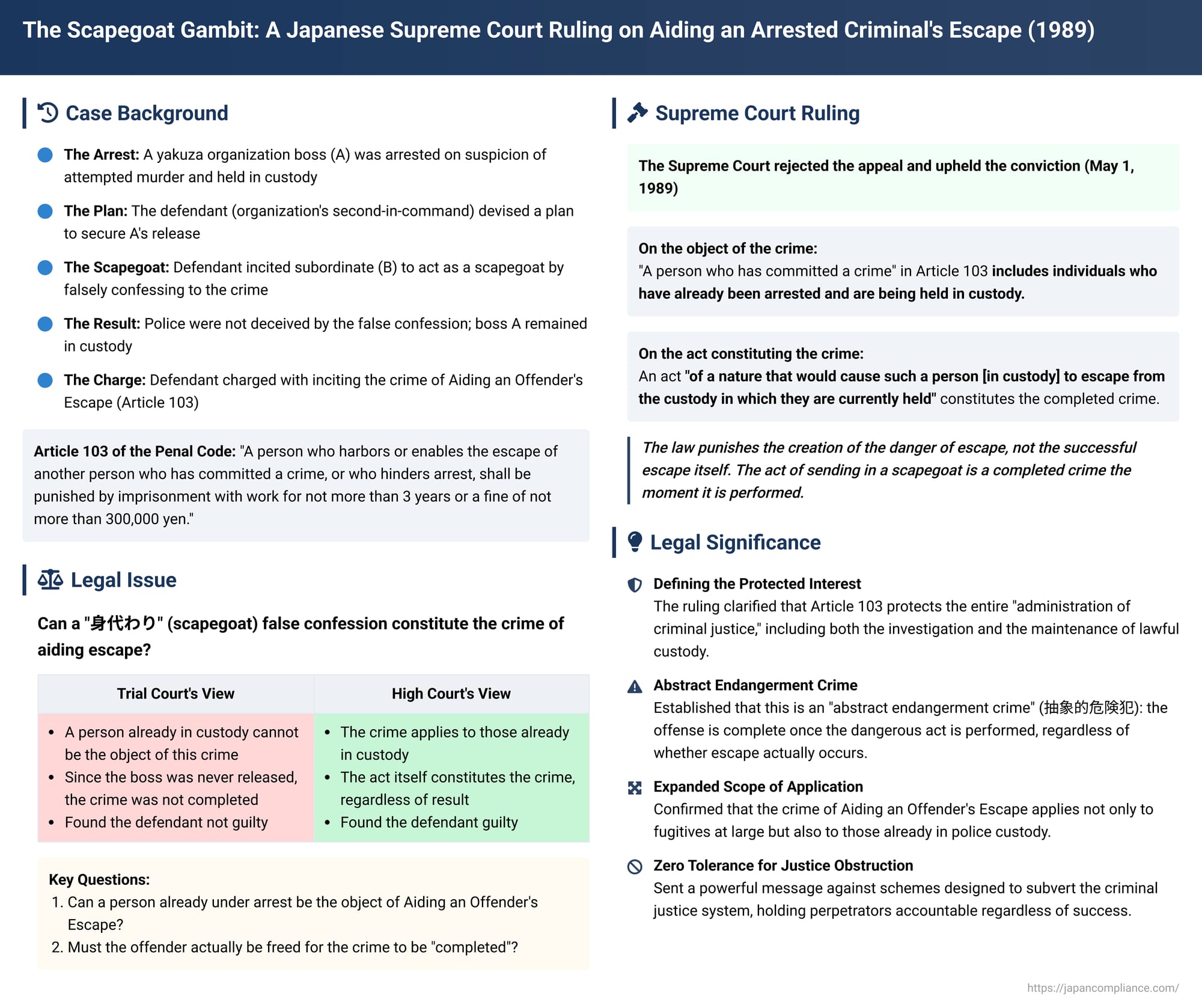

These critical questions were the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on May 1, 1989. The ruling, in a case involving a yakuza organization's attempt to free its arrested leader, clarified the scope of the crime of Aiding an Offender's Escape and established that the act of sending in a scapegoat is a completed crime, regardless of its success.

The Facts: The Yakuza Boss and the Loyal Subordinate

The case arose from within a violent criminal organization.

- The Arrest: The boss of the organization, A, was arrested on suspicion of attempted murder and was being held in custody.

- The Scapegoat Plan: The defendant, who was the organization's second-in-command (wakagashira), devised a plan to secure A's release. He incited a subordinate member of the group, B, to act as a scapegoat.

- The False Confession: Following the defendant's instructions, B went to the police station and falsely confessed to being the person who committed the attempted murder for which his boss, A, had been arrested.

- The Failed Result: The police, however, were not deceived by B's confession. They did not believe his story and, consequently, they did not release the boss, A.

The defendant was charged with inciting the crime of Aiding an Offender's Escape (a violation of Article 103 of the Penal Code). The trial court acquitted him, reasoning that (1) a person already in custody cannot be the object of this crime, and (2) since the boss was never released, the crime was not completed. The High Court reversed this, and the defendant appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: Aiding an Escape from Jail?

The case presented two fundamental legal questions:

- Can a person who is already under arrest be the object of the crime of Aiding an Offender's Escape, or does the crime only apply to harboring fugitives who are still at large?

- For the crime to be "completed," must the offender actually be freed, or is the act of trying to free them sufficient, even if it fails?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Creating the Danger is the Crime

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's appeal and upheld the conviction. The Court's decision clarified both key issues.

- An Arrested Person Can Be the Target: The Court first affirmed that the object of the crime, "a person who has committed a crime," includes individuals who have already been arrested and are being held in custody. It reasoned that the purpose of the law is to punish those who obstruct the broad administration of criminal justice, which includes not only investigation but also the proper maintenance of custody and the execution of sentences.

- The Act Itself is the Crime: The Court then addressed the meaning of "to conceal or aid the escape of" (inpi saseta). It ruled that an act "of a nature that would cause such a person [in custody] to escape from the custody in which they are currently held" constitutes the completed crime.

In essence, the law punishes the creation of the danger of escape, not the successful escape itself. The act of sending in a scapegoat to falsely confess is, by its very nature, an act designed to cause the release of the true offender and is therefore a completed crime the moment it is performed, regardless of its outcome.

Analysis: What Does This Crime Actually Protect?

The Supreme Court's decision is significant because it navigates a complex theoretical debate about the precise "protected interest" of this crime.

- The Limited View (Protecting Custody): This view, adopted by the trial court, argues that the law only protects the state's interest in securing and maintaining physical custody of an offender. From this perspective, if custody is never actually broken, no crime is completed.

- The Broad View (Protecting the Whole Judicial Process): This view, adopted by the High Court, argues that the law protects the entire administration of justice, including the correct identification of the offender. From this perspective, sending in a scapegoat harms the judicial process by obstructing the investigation, and this harm is sufficient to complete the crime.

- The Supreme Court's Subtle Path: The Supreme Court's reasoning is nuanced. While it defines the protected interest very broadly as the entire "administration of criminal justice," it decided this specific case on the narrower and more concrete ground of endangering custody. The Court found that the act of sending in a scapegoat is inherently an attack on the state's lawful custody of the real offender because its purpose is to secure their release.

- An "Abstract Endangerment" Crime: This approach effectively treats the crime as an "abstract endangerment crime." This means the offense is complete once the dangerous act itself is performed, regardless of whether the ultimate harmful result (the escape) materializes. The act of sending a false confessor to the police is deemed dangerous enough to the justice system to be punished as a completed crime. This is similar to the crime of defamation, where the crime is complete upon the defamatory act, without requiring proof that the victim's reputation was actually lowered.

Conclusion

The 1989 "scapegoat" decision is a crucial ruling that clarifies the scope of the crime of Aiding an Offender's Escape in Japan. It authoritatively established two key principles: first, the law protects against attempts to free criminals who are already in police custody, not just those who are at large. Second, the crime is complete when the dangerous act of obstruction is performed, regardless of whether the plan succeeds. The ruling sends a powerful message that the law will not tolerate schemes designed to subvert the criminal justice system, and that those who attempt to obstruct justice by creating a scapegoat will be held fully accountable for their actions, whether their ploy works or not.