The "Saiyo Naitei" (Informal Job Offer) in Japan: The Landmark Dainippon Printing Supreme Court Judgment

Judgment Date: July 20, 1979

Case Name: Claim for Confirmation of Employment Relationship and Payment of Wages (Known as the Dainippon Printing Case)

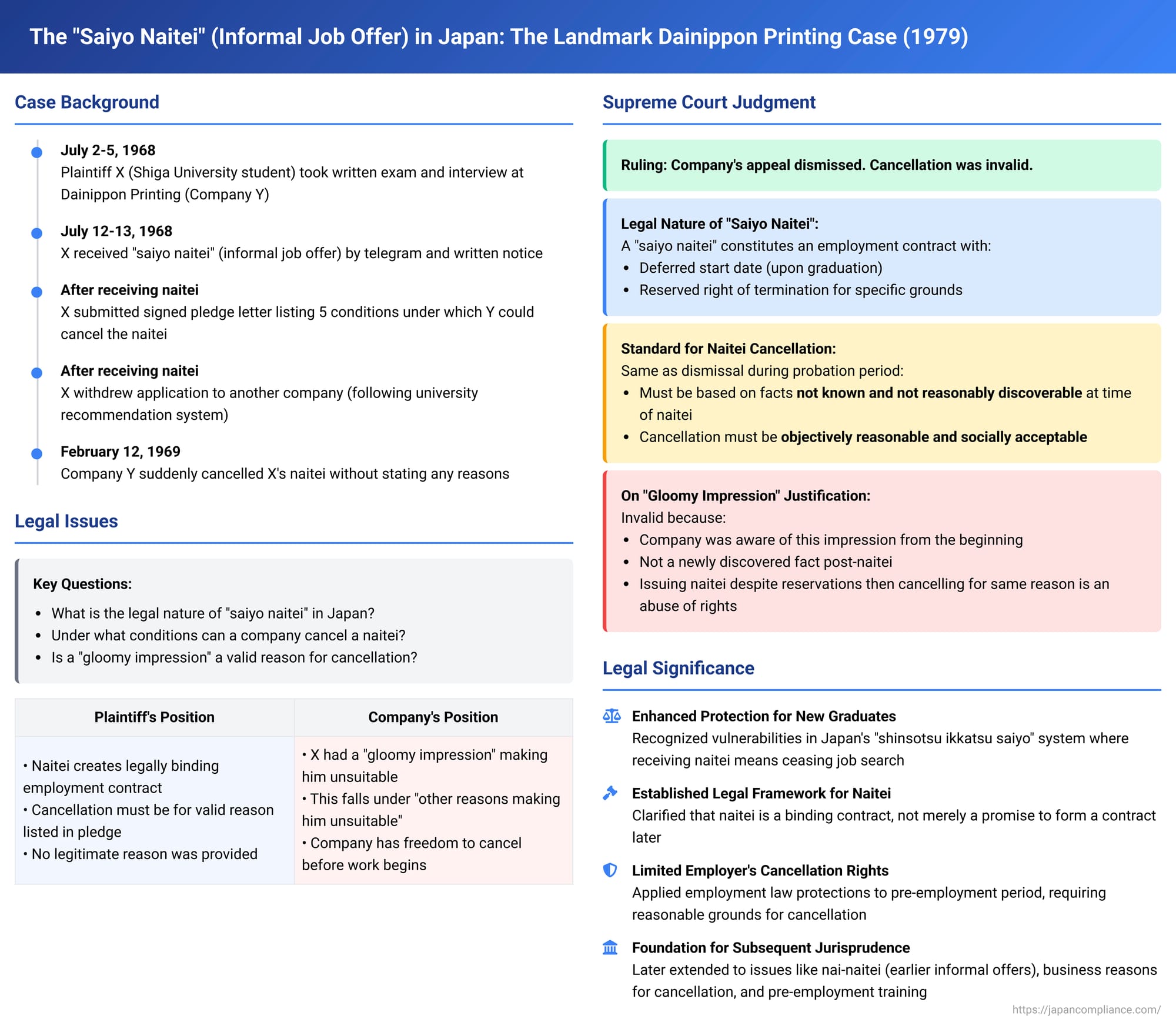

In Japan's unique employment landscape, particularly characterized by the "shinsotsu ikkatsu saiyo" (simultaneous recruitment of new graduates) system, the concept of "saiyo naitei" (an informal promise or offer of employment, typically given to students well before graduation) holds significant legal and practical importance. The Supreme Court of Japan's Second Petty Bench judgment in the Dainippon Printing Co. case, delivered on July 20, 1979, was a watershed moment, providing crucial clarification on the legal nature of these offers and the protections afforded to individuals who receive them.

Factual Background of the Dainippon Printing Case

The plaintiff, X, was a student at Shiga University. Following a recommendation from his university, he applied for a position at Company Y, a major printing company. He underwent a written examination and aptitude test on July 2, 1968, submitted a personal history form, and subsequently attended an interview and a medical examination on July 5.

Shiga University, like many Japanese universities at the time, had a practice of recommending students to a limited number of companies (typically no more than two). If a student received a "naitei" from one company, the university would withdraw its recommendation to the other company, and the student would be expected to accept the offer. Company Y was aware of this prevailing system.

On July 12, 1968, X received a telegraphic notification from Company Y stating that he had been given a "saiyo naitei." A formal written notice to the same effect, dated July 12, followed on July 13. As per Company Y's instructions, X submitted a signed pledge letter. In this letter, X affirmed that he would not withdraw his acceptance for personal reasons and acknowledged five specific grounds upon which Company Y could cancel the "naitei":

- False statements in his resume or other application documents.

- Discovery of past involvement in communist movements or similar activities.

- Failure to graduate from university in March of the following year.

- Significant deterioration of his health condition before the commencement of employment, rendering him unfit for work in Company Y's judgment.

- Other reasons that would make him unsuitable for employment after joining the company.

X had also applied to another company, Company B (Daikin Industries, Ltd., according to the original judgment text), but upon receiving the "naitei" from Company Y, he immediately informed Company B, through his university, that he was withdrawing his application.

However, on February 12, 1969, shortly before X was due to graduate and commence employment, Company Y sent him a written notice abruptly canceling the "saiyo naitei." This cancellation notice provided no reasons for the decision. Despite X's repeated requests for an explanation, Company Y declined to specify its grounds for withdrawal. Believing he had a firm commitment from Company Y, X had not pursued other employment opportunities and, due to the late timing of the cancellation, found it practically impossible to secure a comparable position elsewhere.

X subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking confirmation of his status as an employee of Company Y, payment of unpaid wages, and monetary damages for emotional distress. The Otsu District Court and the Osaka High Court both ruled in favor of X, with the High Court awarding 1 million yen in damages. Company Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of X. The judgment provided a detailed analysis of the legal nature of "saiyo naitei":

- Varied Nature of "Saiyo Naitei": The Court began by acknowledging that the practice of "saiyo naitei" is widespread in Japan but its specifics can vary significantly between companies and situations. Therefore, its legal character cannot be defined uniformly and must be determined based on the particular facts of each case, considering the company's practices for that recruitment year.

- Formation of an Employment Contract in This Case: The Court found that in X's situation, no further formal expression of intent to conclude an employment contract was anticipated beyond Company Y's "naitei" notification. It reasoned as follows: Company Y's initial recruitment drive was an "invitation to treat" (an invitation for applications). X's application, made through his university, constituted an "offer" to enter into an employment contract. Company Y's "saiyo naitei" notice was an "acceptance" of X's offer. This acceptance, coupled with X's submission of the pledge letter outlining specific conditions, resulted in the formation of a legally binding employment contract between X and Company Y. This contract stipulated that X's employment would commence immediately after his graduation from university in March 1969. Crucially, the contract included a reserved right for Company Y to terminate it if any of the five conditions specified in the pledge letter were met.

- Status of "Naitei" Holders: The Supreme Court drew a significant parallel, stating that, considering the employment practices in Japan, the status of a new university graduate who has entered into a "saiyo naitei" relationship with a company is "fundamentally no different" from the status of an individual who has been hired subject to a probationary period, during that period. Although the "naitei" holder has not yet commenced work, the expectation of future employment and the relinquishing of other opportunities create a comparable situation of reliance.

- Standard for "Naitei" Cancellation (Applying Probationary Dismissal Rules): Building on the analogy with probationary employment, the Court held that its established legal principles regarding the exercise of a reserved right of termination during a probationary period (as articulated in the Mitsubishi Jushi case, a 1973 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision) are equally applicable to the cancellation of a "saiyo naitei."

Therefore, the grounds for canceling a "saiyo naitei" must be:- Facts that were not known and could not reasonably have been expected to be known by the employer at the time the "naitei" was granted.

- Such that canceling the "naitei" based on these newly discovered facts is objectively reasonable and socially acceptable when considered in light of the purpose for which the right to terminate was reserved.

- Invalidity of Company Y's Stated Reason for Cancellation: The Supreme Court then applied this standard to Company Y's primary justification for canceling X's "naitei," which was X's allegedly "gloomy impression." According to the facts established by the High Court, Company Y had been aware of this "gloomy impression" from the outset but had issued the "naitei" hoping that subsequent positive factors might emerge to counteract this initial assessment. When no such countervailing factors appeared, Company Y decided to cancel.

The Supreme Court found this reasoning unacceptable. Since the "gloomy impression" was a characteristic known to Company Y from the beginning, it was not a newly discovered fact. To grant a "naitei" despite having reservations about an applicant's suitability based on an initial impression, and then to cancel it later because no new information emerged to dispel those reservations, was deemed an abuse of the reserved right of termination. Such an action was not objectively reasonable or socially acceptable in light of the intended purpose of reserving cancellation rights (which is typically to assess suitability based on later-discovered information or performance during a trial period). The "gloomy impression" could not, therefore, be considered a valid reason under the pledge letter's fifth, catch-all category of "other reasons making him unsuitable for work."

Analysis and Significance of the Dainippon Printing Judgment

The Dainippon Printing case is a landmark in Japanese labor law, establishing crucial protections for individuals who receive "saiyo naitei."

- "Saiyo Naitei" as an Employment Contract:

The most significant aspect of the ruling was its clear articulation that a "saiyo naitei," at least in circumstances like those present in the case, constitutes the formation of an employment contract with a deferred start date for work and a reserved right of termination for the employer. This was a groundbreaking step because it brought the cancellation of these informal offers under the purview of employment law, allowing for the application of principles analogous to those governing dismissals. Prior to this, the legal status of "naitei" was ambiguous, with some earlier theories viewing it merely as a "promise to form a contract" or as part of an ongoing contract formation process, which would offer less protection to the applicant. - Context of "Shinsotsu Ikkatsu Saiyo":

The judgment explicitly considered Japan's unique "shinsotsu ikkatsu saiyo" system. Under this system, companies predominantly hire new university graduates simultaneously, well in advance of their graduation. Students who receive a "naitei" typically cease their job-seeking activities, relying on this promise of future employment. A late-stage cancellation can therefore be devastating, leaving them with few, if any, alternative opportunities. The Supreme Court's decision to recognize a contractual relationship at the "naitei" stage provided a legal basis for ensuring the employment status of affected individuals, a remedy often more effective than mere monetary damages. - The Reserved Right of Termination (留保解約権 - Ryūho Kaiyaku-ken):

By equating the "naitei" period with a probationary period, the Court imported the legal framework for dismissals during probation, notably the standard set in the Mitsubishi Jushi case: any termination must be based on "objectively reasonable grounds" and be "socially acceptable." This means that employers cannot arbitrarily cancel a "naitei."

There has been some subsequent judicial evolution and academic debate regarding the scope of permissible cancellation grounds. While the Dainippon Printing judgment appeared to interpret the pledge letter's listed grounds somewhat restrictively in the context of the "gloomy impression" argument, a later Supreme Court case (Denden Kosha Kinki Bureau Case, 1980) suggested that cancellation grounds are not necessarily limited to those explicitly stated in a pledge letter, provided they meet the overarching "objectively reasonable and socially acceptable" standard.

Academics have debated whether equating "naitei" cancellation with probationary dismissal (which allows broader grounds than ordinary dismissal) is entirely appropriate, with some arguing that the risk associated with early talent acquisition should primarily be borne by the employer and that reserved termination rights should ideally only be recognized for grounds explicitly and clearly agreed upon by both parties. - "Objectively Reasonable and Socially Acceptable" Grounds for Cancellation:

The standard established by the Court requires a rigorous assessment of any reasons for "naitei" cancellation. These reasons must typically relate to facts that were unknown and not reasonably discoverable by the employer at the time the "naitei" was issued.- Business Reasons: Many litigated "naitei" cancellations involve reasons related to a downturn in the employer's business. In such cases, courts often apply principles analogous to those governing "seiri kaiko" (dismissals for economic reasons), which involve assessing factors like the necessity of workforce reduction, efforts to avoid dismissals, the rationality of selection criteria, and procedural fairness. Some court decisions and scholarly opinions suggest that selecting a "naitei" recipient (who has not yet commenced work and thus has less established ties to the company) for termination in a downsizing situation might be viewed as less unreasonable compared to dismissing existing employees (e.g., the Informix Case, Tokyo District Court decision).

- Non-Disclosure of Information: Cases have also arisen concerning non-disclosure of personal information. For instance, in a 2019 Sapporo District Court case (Hokkaido Social Welfare Corporation Case), the non-disclosure of HIV infection by a "naitei" recipient was not deemed a valid reason for cancellation where there was no established duty to disclose such information. The objective reasonableness of a cancellation, even if a duty to disclose existed, would likely depend on the direct impact of the condition on the specific job duties and the actual symptoms.

- "Nai-naitei" (Informal Pre-Offers):

It's common in Japan for companies to issue even earlier, more informal expressions of intent to hire, known as "nai-naitei," often before the official date (historically October 1st for many industries, based on business federation guidelines) for issuing formal "naitei." Courts have sometimes found that a "nai-naitei" does not, by itself, constitute a full employment contract, especially if a later, formal "naitei" date is clearly communicated. However, the arbitrary cancellation of a "nai-naitei" might still be considered a breach of the principle of good faith during the contract negotiation process, potentially leading to liability for damages (e.g., Kose R.E. (No. 2) Case, Fukuoka High Court, 2011). - Legal Relationship During the "Naitei" Period:

A related legal question concerns the nature of the legal relationship between the "naitei" date and the actual commencement of employment.- The Dainippon Printing judgment conceptualized the contract as an "employment contract with a deferred start date for work," implying that the contract itself becomes legally effective from the "naitei" date, even though work duties commence later.

- In contrast, the subsequent Denden Kosha Kinki Bureau case characterized it as an "employment contract with a deferred effective date," meaning the contract's legal effects (including most rights and obligations) only begin from the first day of work. This distinction has implications for issues like the legal basis for requiring participation in pre-employment training programs.

- Later court decisions have sometimes adopted the "deferred effective date" model but have used principles of good faith and fair dealing to address obligations during the interim "naitei" period. For example, the Sendenkaigi Case (Tokyo District Court, 2005) held that participation in pre-employment training should be based on the voluntary consent of the "naitei" recipient, and employers have a good faith obligation to excuse non-participation for reasonable grounds, such as academic commitments, without imposing disadvantages.

- Academic opinion varies, with some supporting the "deferred effective date" view. However, an interpretation favoring a "deferred work start date" (making the contract effective from "naitei" for status purposes), coupled with the application of good faith principles to regulate the rights and duties during the interim period, is often seen as better reflecting corporate realities and aligning with the protective intent of the "naitei" doctrine, which was to advance the point of contract formation to provide more robust remedies against unwarranted cancellations.

Concluding Thoughts

The Dainippon Printing Supreme Court judgment was a landmark decision that significantly enhanced the legal protection for job applicants, particularly new graduates, in Japan. By recognizing the formation of an employment contract at the "saiyo naitei" stage, albeit one with a reserved right of termination for the employer, the Court subjected "naitei" cancellations to legal scrutiny based on principles of objective reasonableness and social acceptability. This ruling acknowledged the substantial reliance placed by applicants on these informal offers and the severe detriment caused by late-stage withdrawals. While Japanese employment practices, including recruitment methods, continue to evolve, the principles established in the Dainippon Printing case remain a cornerstone of labor law, ensuring a degree of fairness and security for individuals on the cusp of their careers. The judgment’s emphasis on a case-by-case factual analysis also ensures its continued relevance in adapting to diverse and changing employment scenarios.