The Rogue Agent and the Promissory Note: Japan's Landmark Forgery Case

In the world of corporate governance, the authority to bind a company financially is a potent and carefully controlled power. Employees and managers are often granted the ability to act on behalf of their organization—signing contracts, issuing checks, or creating promissory notes—but this authority is almost always subject to internal rules, such as spending limits or the need for a superior's approval. What happens when an agent, who has the general power to create a financial instrument, does so by violating a crucial internal rule? Is this merely an internal policy breach, or is it the serious crime of document forgery? And does it matter if the resulting document might still be legally enforceable against the company by an innocent third party?

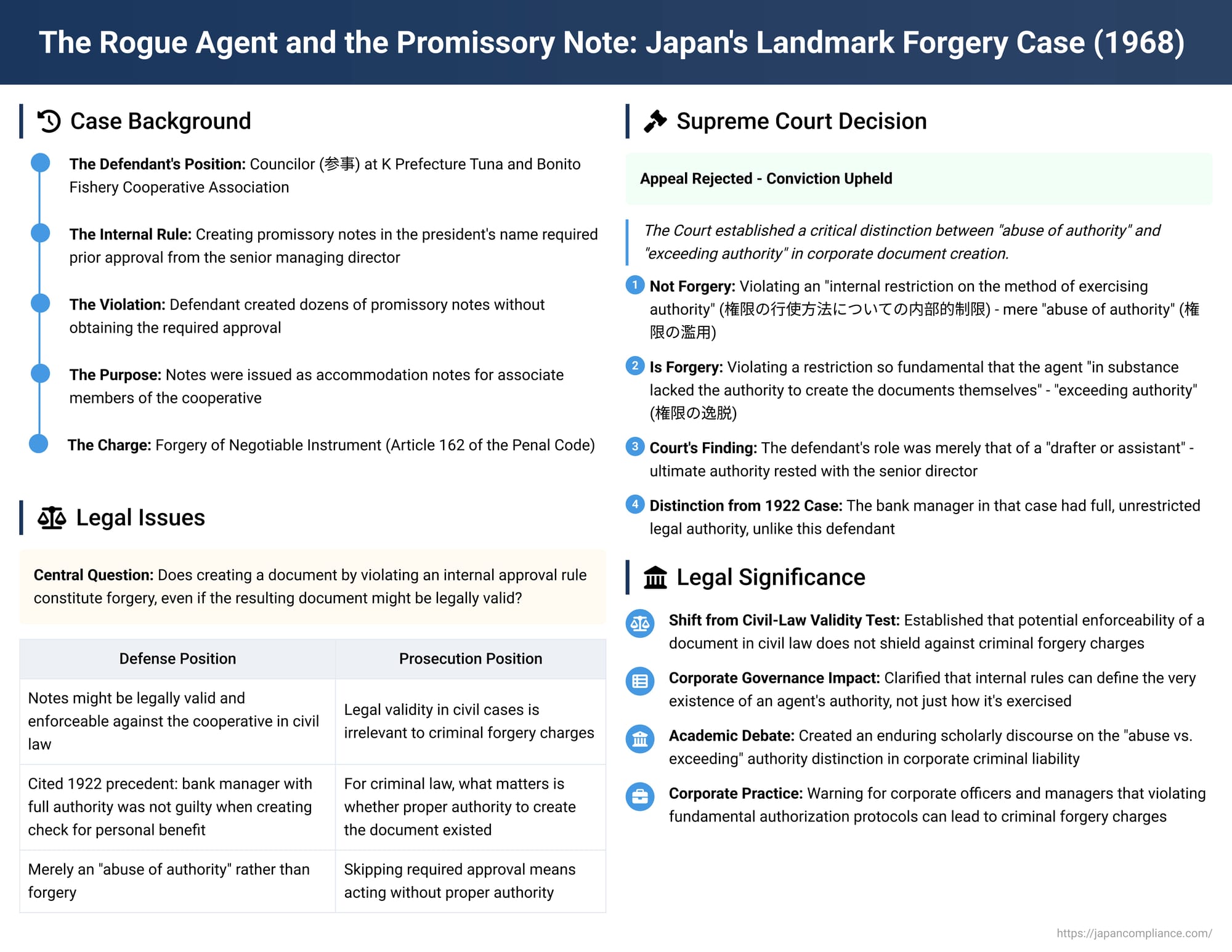

This fundamental question of agency, authority, and criminal law was at the center of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on June 25, 1968. The case, involving a fishery cooperative councilor who issued unauthorized promissory notes, established a critical distinction between the "abuse of authority" and the "exceeding of authority" that continues to shape Japanese white-collar criminal law.

The Facts: The Councilor and the Unapproved Notes

The case involved a defendant, A, who held the title of councilor (sanji) at the K Prefecture Tuna and Bonito Fishery Cooperative Association.

- His Role: His duties included handling the issuance of promissory notes.

- The Internal Rule: To issue a promissory note in the name of the association's president, there was a strict internal rule requiring him to obtain the prior approval of the senior managing director, B.

- The Violation: Without receiving this mandatory approval, Defendant A proceeded to create dozens of promissory notes in the president's name. These were issued as accommodation notes for the benefit of associate members of the cooperative.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of Forgery of a Negotiable Instrument (Article 162 of the Penal Code) by the lower courts. The defense appealed, arguing that since the promissory notes might be legally valid in a civil action brought by a good-faith third party, their creation could not be a criminal forgery.

The Legal Conundrum: Abuse of Power or Lack of Power?

The defense's argument was a powerful one, with roots in a famous 1922 precedent from Japan's pre-war high court. That older case had acquitted a bank manager with full authority who had created a check for his own personal benefit, reasoning that if a resulting document is legally valid and binds the principal, the public's trust is not harmed, and thus there is no forgery. The defendant in the 1968 case was arguing for the same logic: he may have abused his authority, but he did not act without it, and the potential validity of the notes should preclude a forgery conviction.

The lower appellate court acknowledged that the notes might indeed be legally enforceable against the cooperative by an innocent third party under commercial law. However, it still found the defendant guilty, reasoning that for the criminal law, the ultimate question is whether the creator had the proper authority to create the document, and in this case, by skipping the required approval, he did not.

The Supreme Court's Crucial Distinction

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal and upheld the conviction. In doing so, it sidestepped the question of the notes' civil-law validity and instead focused entirely on the nature of the defendant's authority. The Court's ruling drew a fine but critical distinction:

- It is not forgery if an agent with authority merely violates an "internal restriction on the method of exercising authority." This would be a mere "abuse of authority" (kengen no ran'yō).

- It is forgery, however, if the internal restriction is so fundamental that it means the agent, "in substance... lacked the authority to create the notes themselves." This is a case of "exceeding authority" (kengen no itsudatsu).

Applying this test to the facts, the Court found that the defendant's situation fell into the second category. The internal rule requiring the senior director's approval was not a mere procedural formality. It meant that the ultimate authority to create these notes rested solely with the senior director. The defendant's role, the Court concluded, was merely that of a "drafter or assistant." By creating the notes without the director's approval, he was not just improperly exercising a power he had; he was usurping a power he never possessed in the first place. The Court distinguished this from the 1922 precedent by noting that the bank manager in that case had full, unrestricted legal authority, making his actions a true abuse of power, not a lack of it.

Analysis: The Shifting Tides of Forgery Law

This 1968 decision was significant for marking a decisive shift by the Supreme Court away from the "civil-law validity" test that the 1922 case seemed to establish. The Court made it clear that the potential enforceability of a document in a civil suit, a principle designed to protect innocent third parties in commercial transactions, would not serve as a shield against criminal liability for forgery.

The ruling remains a central focus of academic debate in Japan.

- The Majority Scholarly View: Most scholars support the Court's distinction between "abuse" and "exceeding" authority. This view holds that the principal of an organization has the right to set the substantive limits of an agent's power. Violating a fundamental limit on who can create a document is forgery, while violating a procedural rule on how to create it is merely an abuse.

- The "Civil Law Validity" Theory: A minority of scholars maintain that if a negotiable instrument is legally valid and enforceable against the principal, there is no harm to the public's trust and therefore no forgery. From this perspective, the defendant in this case should have been acquitted. This view is criticized, however, on the grounds that civil-law validity is a separate issue designed to protect third parties, not to legitimize the agent's unauthorized act.

- Intermediate Theories: Other prominent scholars have proposed more complex intermediate theories. Dr. Hirano Ryuichi, for example, argued that forgery occurs only if the document is not "completely" valid (i.e., if it is unenforceable against a party acting in bad faith). This view, however, has also been criticized as difficult to apply and not fully consistent with the body of case law.

Conclusion

The 1968 ruling on the rogue councilor and his unapproved promissory notes is a vital precedent for corporate officers, managers, and anyone acting under delegated authority. It establishes that for the purposes of criminal forgery, the internal rules and authorization protocols of an organization are not mere suggestions. The key question is whether a violated rule was a simple procedural guideline or a fundamental limitation that defined the very existence of one's authority. Violating a procedural rule may lead to internal discipline; usurping a fundamental authority one does not possess can lead to a criminal conviction for forgery. This decision serves as a critical warning that the line between an internal misstep and a serious crime is drawn by the substantive nature of the power one has been entrusted with.