The Rightful Claim and the Wrongful Threat: A Japanese Ruling on Extortion and Debt Collection

Imagine a person is owed a legitimate debt, but the debtor simply refuses to pay. Frustrated with the formal legal process, the creditor decides to take matters into their own hands. They confront the debtor and use threats of violence to "persuade" them to pay up. Is this a justifiable, if aggressive, exercise of their right to collect a debt? Or is it the crime of extortion? And if the debtor, under duress, pays more than they owed, is the crime limited to the excess amount, or is the entire transaction tainted by the illegal means?

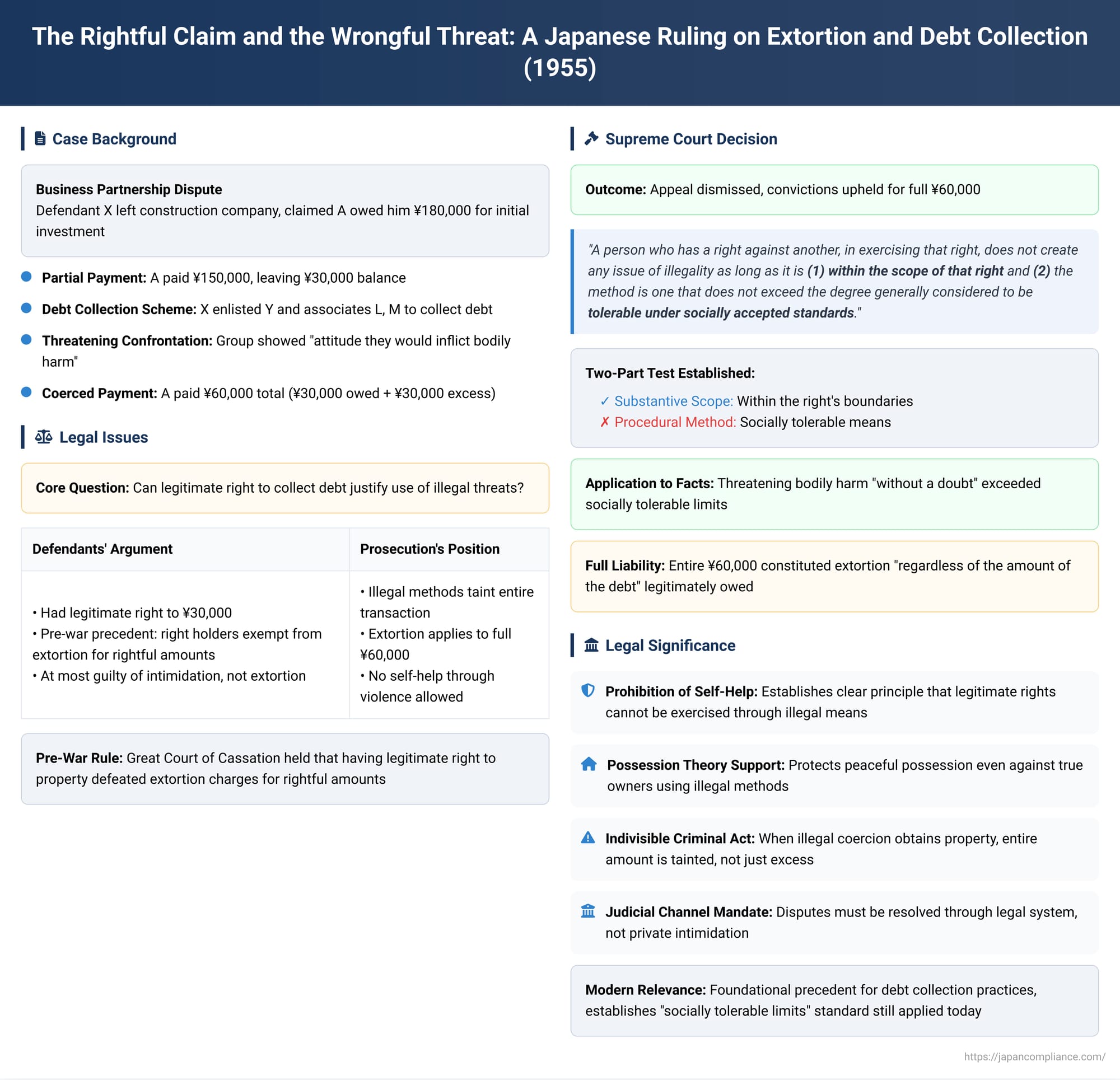

This fundamental conflict between a rightful claim and a wrongful method was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on October 14, 1955. The Court's ruling established a clear and enduring test for when the act of exercising a right crosses the line into criminality, affirming that the law protects not just the substance of a right, but also the lawful and socially acceptable means of its execution.

The Facts: The Business Dispute and the Hired Muscle

The case began with a business dispute. The defendant, X, upon leaving a construction company he had co-founded with a man named A, claimed that A owed him approximately 180,000 yen for his initial investment. After a dispute, A agreed to pay this amount and made an initial payment of 150,000 yen, leaving an outstanding balance of 30,000 yen.

When A failed to pay the remaining 30,000 yen, X enlisted the help of his friend, defendant Y, to collect the debt. Y, in turn, brought in two more associates, L and M. The four men then conspired not only to collect the 30,000 yen debt but to extort additional money from A.

The group confronted A, "showing an attitude that they would inflict bodily harm" if he did not comply with their demands. They made intimidating statements such as, "Save our face." Fearing for his physical safety, A was coerced into handing over a total of 60,000 yen—the 30,000 yen he owed, plus an additional 30,000 yen.

The defendants were charged with and convicted of extortion for the full 60,000 yen. On appeal, they argued that their actions were for the purpose of collecting a legitimate debt. Citing older precedents, they claimed that while their methods might constitute the lesser crime of intimidation, their act could not be extortion, at least with respect to the 30,000 yen they were rightfully owed.

The Legal Question: The "Exercise of a Right" as a Defense to Extortion

The defendants' argument was based on a line of pre-war case law from the Great Court of Cassation. Those older rulings had established a principle that if a person had a legitimate right to obtain property, using coercive means to get it was not extortion, so long as they took no more than what they were owed. This effectively treated the existence of a right as a defense to the crime.

The 1955 Supreme Court was thus faced with a clear question: should this old rule stand, or does the use of illegal methods transform a rightful claim into a criminal act?

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: The "Socially Tolerable Limits" Test

The Supreme Court rejected the defendants' appeal and the old legal standard. It established a new, two-part test for determining when the exercise of a right is lawful. The Court declared:

"A person who has a right against another, in exercising that right, does not create any issue of illegality as long as it is (1) within the scope of that right and (2) the method is one that does not exceed the degree generally considered to be tolerable under socially accepted standards."

The Court's key holding was that if an act "deviates from said scope or degree, it becomes illegal, and the crime of extortion may be established."

Applying this test to the facts, the Court found that the defendants' method—showing an attitude that they would inflict bodily harm and making intimidating demands—was "without a doubt, a means that deviates from the degree generally considered to be tolerable" for the exercise of a right.

Because the means were illegal, the entire transaction was tainted. The Court concluded that the lower court was correct to find the defendants guilty of extortion for the full 60,000 yen, "regardless of the amount of the debt" that X was legitimately owed.

Analysis: Prohibiting Self-Help and Protecting Possession

The Supreme Court's 1955 decision represents a fundamental policy choice in criminal law: the prohibition of "self-help" and the maintenance of social peace are paramount, even over an individual's substantive property rights. The law demands that disputes be resolved through legal channels, not through private force and intimidation.

This ruling aligns with the modern trend in Japanese property crime jurisprudence, often referred to as the "Possession Theory." This theory holds that the law protects the peaceful, factual possession of property. Even a person who is not the "true owner" of an object has a right to their peaceful possession of it, and the true owner cannot use illegal means to take it back. In this case, the debtor, A, had peaceful possession of his 60,000 yen. The creditor, X, despite his right to 30,000 yen of it, was not entitled to use illegal threats to disturb that possession. His right had to be pursued through lawful means.

The Court's decision to hold the defendants liable for the full 60,000 yen is also significant. It establishes that when property is obtained through an indivisible act of illegal coercion, the law will not parse the proceeds to give the perpetrator credit for their underlying claim. The entire amount obtained is considered the fruit of the criminal act.

Conclusion: A Clear Warning to Creditors

The 1955 Supreme Court decision remains a foundational ruling on the limits of self-help in debt collection and the exercise of rights. It established a clear and enduring principle: having a right to property or money is not a license to use illegal means to obtain it.

The legacy of the ruling is its two-part test. An act is only a legitimate exercise of a right if it is both substantively within the scope of the right and procedurally within the bounds of socially acceptable methods. If the methods used—such as threats of violence—are illegal, the act ceases to be a legitimate exercise of a right and becomes a crime. This decision sends a powerful and unambiguous message that the legal system demands the resolution of disputes through its own channels, not through private intimidation, and it will treat those who resort to such methods as extortionists, not as rightful claimants.