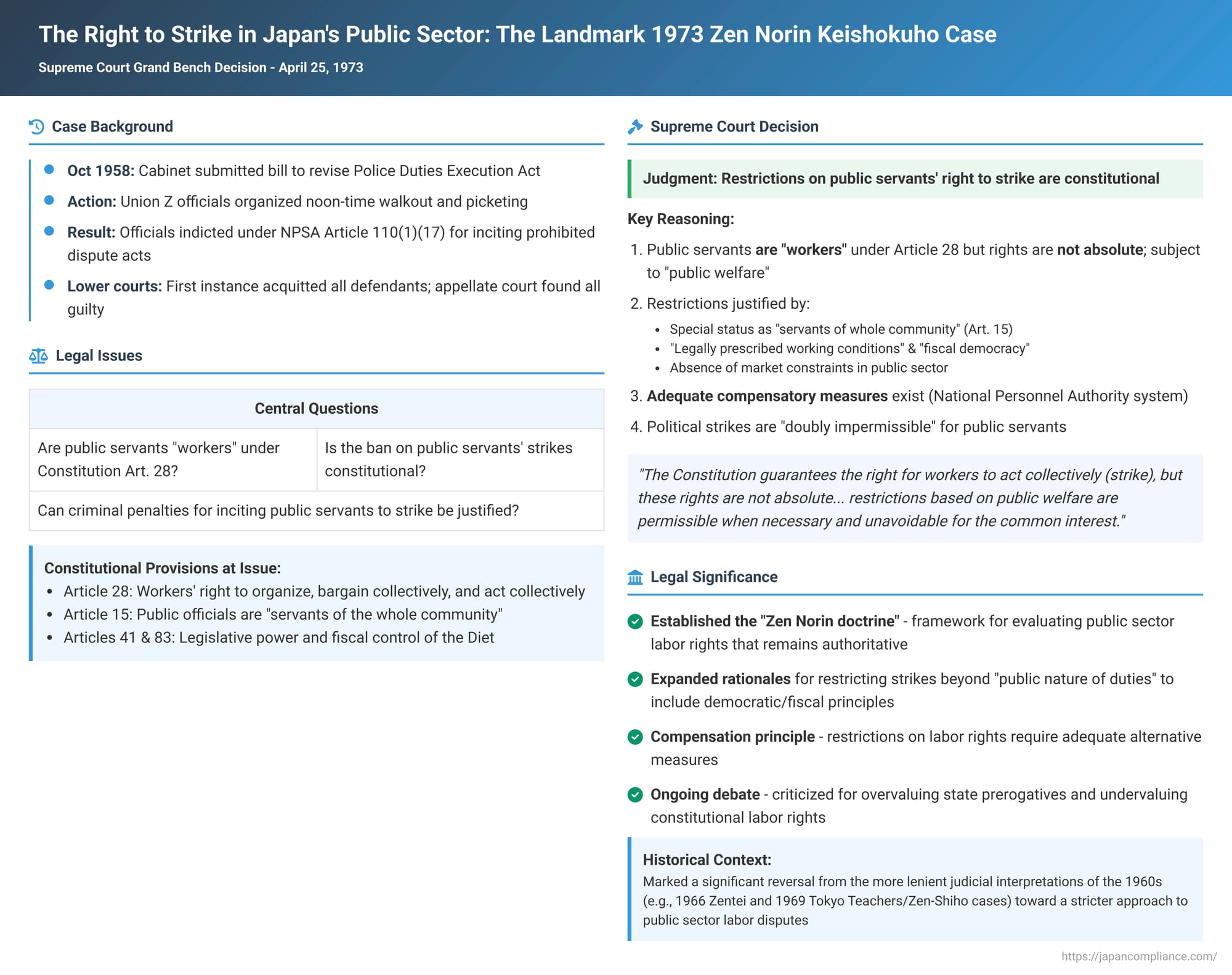

The Right to Strike in Japan's Public Sector: The Landmark 1973 Zen Norin Keishokuho Supreme Court Judgment

Judgment Date: April 25, 1973

Case Name: National Public Service Act Violation Case (Known as the Zen Norin Keishokuho Case)

The extent to which public servants in Japan can exercise fundamental labor rights, particularly the right to engage in dispute acts such as strikes, has been a subject of intense legal and social debate. A pivotal moment in this discourse was the Supreme Court of Japan's Grand Bench judgment in the "Zen Norin Keishokuho Case," delivered on April 25, 1973. This ruling established a foundational legal doctrine that continues to shape public sector labor relations in Japan, balancing the rights of public employees as workers against the perceived needs of public service continuity and democratic governance.

Factual Background of the Zen Norin Keishokuho Case

The case arose in October 1958 when the Japanese Cabinet submitted a bill to the Diet proposing revisions to the Police Duties Execution Act. This proposed legislation sparked significant opposition from labor organizations, including Federation S (a major national labor federation) and Union Z (the All Japan Agriculture and Forestry Ministry Workers' Union). These groups feared that the revised act could be used to suppress the labor movement.

In protest, officials of Union Z (the defendants in the case) issued a directive to its branch offices for its members, who were non-operational national public servants at the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (the Ministry), to engage in a "struggle by force" – specifically, a noon-time walkout. On the day of the planned action, they also organized pickets at the entrances of the Ministry's buildings, urging Ministry employees to participate in a workplace rally opposing the bill.

As a result of these actions, the Union Z officials were indicted under Article 110(1)(17) of the National Public Service Act (NPSA) (the version prior to the 1965 amendment) for inciting national public servants to engage in dispute acts, which were prohibited by the NPSA. The court of first instance acquitted all defendants. However, the appellate court overturned this decision and found them all guilty. The defendants then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (1973)

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench dismissed the defendants' appeal, upholding their convictions. The judgment laid out a comprehensive legal framework for understanding the scope of, and limitations on, public servants' labor rights.

- Public Servants as "Workers" Entitled to Fundamental Labor Rights:

The Court unequivocally affirmed that public servants, like their private-sector counterparts, are "workers" (勤労者 - kinrōsha) within the meaning of Article 28 of the Japanese Constitution. Article 28 guarantees workers the right to organize, to bargain collectively, and to act collectively (including the right to strike). The Court reasoned that public servants, by providing their labor to earn a livelihood, are fundamentally no different from other workers in this respect. Therefore, the constitutional protection of fundamental labor rights extends to them. - Fundamental Labor Rights Are Not Absolute:

However, the Court emphasized that these fundamental labor rights are not absolute or ends in themselves. They are recognized as means for workers to improve their economic standing. As such, they are inherently subject to restrictions based on the "public welfare" (公共の福祉 - kōkyō no fukushi), interpreted here as the common interest of all citizens, including workers themselves. This, the Court stated, is consistent with the purport of Article 13 of the Constitution (which concerns the respect for individuals and the public welfare). - Justifications for Restricting Public Servants' Right to Strike:

The Court then detailed its reasons for why restricting the labor rights of non-operational national public servants, particularly their right to engage in dispute acts, is constitutionally permissible:- Special Status and Public Nature of Duties: Referencing Article 15 of the Constitution (which states that all public officials are servants of the whole community), the Court highlighted the unique position of public servants. Their employer, in a substantive sense, is the entire populace, and their duty to provide labor is owed to all citizens. While this alone does not justify denying all labor rights, the special status and public nature of their duties mean that restrictions, to the extent necessary and unavoidable, are reasonably justified. Dispute acts by public servants are deemed incompatible with this special status and public nature, as they inevitably lead to the stoppage or impairment of public services, which can gravely impact, or risk impacting, the common interest of all citizens.

- Principle of Legally Prescribed Working Conditions and Fiscal Democracy: The Court distinguished the determination of working conditions for public servants from that in the private sector. Public servants' remuneration is primarily funded by taxes, and their working conditions are to be appropriately determined through political, fiscal, social, and other rational considerations. Crucially, these decisions are to be made democratically within the legislature (the Diet). There is no room, the Court argued, for allowing these conditions to be coerced by the pressure of dispute acts like strikes. The Constitution itself (Article 73(4)) stipulates that the Cabinet shall administer civil service affairs in accordance with standards established by law. Thus, salaries and other working conditions are, in principle, determined by laws and budgets enacted by the Diet, representing the people. The extent to which decision-making power is delegated to the government (as the employer) is a matter of labor policy for the Diet to decide through legislation. Therefore, if public servants engage in dispute acts over matters not lawfully delegated to the government, it would lead to an impasse on legislative issues that the government cannot resolve. This would distort the democratic process for determining public servants' working conditions and could even undermine the principles of parliamentary democracy (citing Constitution Articles 41 and 83) and infringe upon the Diet's legislative powers.

- Absence of Market Countervailing Forces: In private enterprises (except for highly essential public utilities), employers possess countermeasures like lockouts. Moreover, excessive demands by workers are naturally constrained by market forces, as such demands could jeopardize the enterprise's viability and, consequently, the workers' own employment. In contrast, these market mechanisms do not operate in the public sector. As a result, dispute acts by public servants can, in some cases, become unilaterally powerful pressures, further distorting the process for determining their working conditions.

- The Necessity and Adequacy of Compensatory Measures:

Given that the Constitution guarantees fundamental labor rights to public servants, any restriction on these rights necessitates the provision of appropriate alternative or "compensatory" measures (代償措置 - daishō sochi). The Court found that Japan's legal system provided such measures:- The NPSA and other laws contain detailed and meticulous provisions concerning working conditions, status, appointment and dismissal, service discipline, and remuneration.

- The National Personnel Authority (NPA), a quasi-judicial body, is established as a central personnel administration agency. The NPA is mandated to make recommendations or reports to the Diet and Cabinet regarding public servants' working conditions, adhering to the "principle of adaptation to prevailing conditions" (情勢適応の原則 - jōsei tekiō no gensoku), to ensure their appropriateness.

- Public servants have avenues to seek redress, such as requesting administrative measures or filing appeals against adverse actions with the NPA.

The Court concluded that these institutional arrangements constituted adequate compensatory measures for the restrictions imposed on public servants' labor rights.

- Conclusion on Constitutionality:

In light of the public nature of their duties and the existence of these compensatory measures, the Court held that the NPSA's prohibition of dispute acts by public servants (then Article 98(5), later Article 98(2)) and related acts of incitement was a "necessary and unavoidable restriction from the viewpoint of the common interest of all citizens, including workers" and, therefore, did not violate Article 28 of the Constitution. The penal provision (then Article 110(1)(17)) for inciting such illegal dispute acts was also deemed constitutional, as those who incite play a pivotal role and bear greater social responsibility than mere participants. - Specific Finding on the Defendants' Actions (Political Strike):

The Court observed that the defendants' actions and the dispute act they incited (the workplace rally involving work stoppage) were for the political purpose of opposing the revision of the Police Duties Execution Act. It stated that the right to dispute, recognized as a means for improving workers' economic status, does not confer a special privilege to use such acts as a tool to achieve political assertions. Such politically motivated dispute acts, therefore, are not specially protected as freedom of expression under Article 21 of the Constitution. For public servants, whose dispute acts are already prohibited by a constitutional law, engaging in such acts for political purposes is "doubly impermissible." Inciting such prohibited acts, even if it has an aspect of expressing an idea, oversteps the bounds of constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech as it encourages a serious dereliction of duty by public servants and risks gravely impairing the common interest of all citizens.

The Evolution of Judicial Interpretation on Public Sector Strikes

The 1973 Zen Norin Keishokuho judgment was not rendered in a vacuum. It represented a significant point in the Supreme Court's evolving jurisprudence on this issue:

- Early Post-War Period: Initially, the Supreme Court upheld the ban on public servant strikes, emphasizing their role as "servants of the whole community" and their duty to the public interest (e.g., the 1953 JNR Hirosaki Depot Case).

- The 1960s – A Shift Towards Balancing: The mid-1960s saw a doctrinal shift. Cases like the 1965 Wakayama Prefecture Teachers' Union Case began to speak of a "proper balance" between labor rights and public welfare. The 1966 Zentei Tokyo Central Post Office Case went further, suggesting that restrictions on labor rights must be "minimum necessary" and even implied that otherwise legitimate dispute acts violating the ban might be exempt from criminal punishment.

- 1969 Judgments – Restrictive Interpretation for Constitutionality: Two influential Grand Bench judgments in 1969 (the Tokyo Metropolitan Teachers' Union Case and the Zen-Shiho Sendai Case) adopted a more restrictive interpretation of the penal provisions for inciting public servant strikes. They held that such provisions were constitutional only if penalties were limited to situations where the dispute act itself was highly illegal and the act of incitement was not a "normally accompanying act" (通常随伴行為 - tsūjō zuihan kōi) of such a dispute. This approach aimed to narrow the scope of criminal liability.

The Zen Norin Doctrine: Enduring Principles and Criticisms

The 1973 Zen Norin Keishokuho judgment marked a decisive turn from the immediately preceding, more lenient interpretations of the 1960s. It established a doctrine that has largely remained the cornerstone of Japanese law concerning public sector strikes.

- Reaffirmation and Broadening of Rationales for the Ban:

While earlier judgments had focused primarily on the "public nature of duties," the Zen Norin decision explicitly added and emphasized:- Parliamentary Sovereignty in Determining Working Conditions: The "principle of legally prescribed working conditions" (勤務条件法定主義 - kinmu jōken hōtei shugi) and "fiscal democracy" (財政民主主義 - zaisei minshu shugi) became central justifications. This argument posits that since public servants' terms are set by law and budget through the democratically elected Diet, dispute acts aimed at influencing these terms would usurp legislative authority.

- Absence of Market Constraints: Unlike private sector disputes, where market forces can temper demands, the Court argued that no such countervailing pressures exist in the public sector.

These new rationales were seen as particularly potent for justifying strike bans even for public corporation employees, whose duties might seem less directly tied to core governmental functions. (The Supreme Court later heavily relied on the "fiscal democracy" argument in the 1977 Zentai Nagoya Central Post Office Case concerning public corporation employees).

- Emphasis on Compensatory Measures:

A significant aspect of the Zen Norin doctrine is its insistence that restrictions on fundamental labor rights must be counterbalanced by adequate compensatory measures. The Court found the existing system, centered on the National Personnel Authority (NPA) and its recommendation powers, along with detailed legal frameworks for employment conditions and grievance procedures, to be sufficient. This stance has been consistently upheld, even in later cases where the full implementation of NPA recommendations (e.g., due to wage freezes) was challenged. The Court generally found that such issues did not render the compensatory system non-functional to a degree that would make strikes lawful (e.g., the 2000 Zen Norin (1982 Autumn/Year-End Struggle) Case). - Persistent Criticisms of the Doctrine:

Despite its enduring status, the Zen Norin doctrine has faced substantial criticism:- Undue Deference to State Prerogatives: Critics argue that the Supreme Court gives excessive weight to concepts like "fiscal democracy" and the "special status" of public servants, while significantly undervaluing the constitutional guarantee of fundamental labor rights.

- Misunderstanding of Collective Bargaining: Some commentators suggest that the Court's view, particularly in related cases like Zentai Nagoya, that collective bargaining might imply "co-determination" of terms, led it to perceive an inherent conflict with parliamentary democracy. Critics counter that collective bargaining primarily involves negotiation and does not necessarily grant unions the power to co-determine terms or impose a duty on the employer to reach an agreement. They argue that collective bargaining for public servants can be structured to be compatible with democratic legislative processes.

- Perception of Dispute Acts: A fundamental disagreement often lies in whether public servant dispute acts aimed at influencing legislative or budgetary decisions should be viewed as an illegitimate threat to democracy or as an acceptable, albeit potentially disruptive, means for dependent workers to voice their concerns to their ultimate employer, the public, via its representatives.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1973 Zen Norin Keishokuho Supreme Court judgment remains the definitive statement on the restriction of labor dispute rights for a large segment of public servants in Japan. It established a robust legal framework justifying such restrictions based on the unique nature of public service, the principles of parliamentary democracy in setting working conditions, and the perceived adequacy of compensatory mechanisms. While this doctrine has provided legal stability, it continues to be a focal point of debate among legal scholars and labor advocates. Calls for legislative reform, taking into account the evolving realities of public sector labor relations and international labor standards, persist, suggesting that the balance between public servant labor rights and public interest considerations will remain a dynamic area of discussion in Japan.