The Right to Refuse: A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Religious Beliefs and Medical Treatment

Date of Judgment: February 29, 2000

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, 1998 (O) No. 1081, No. 1082

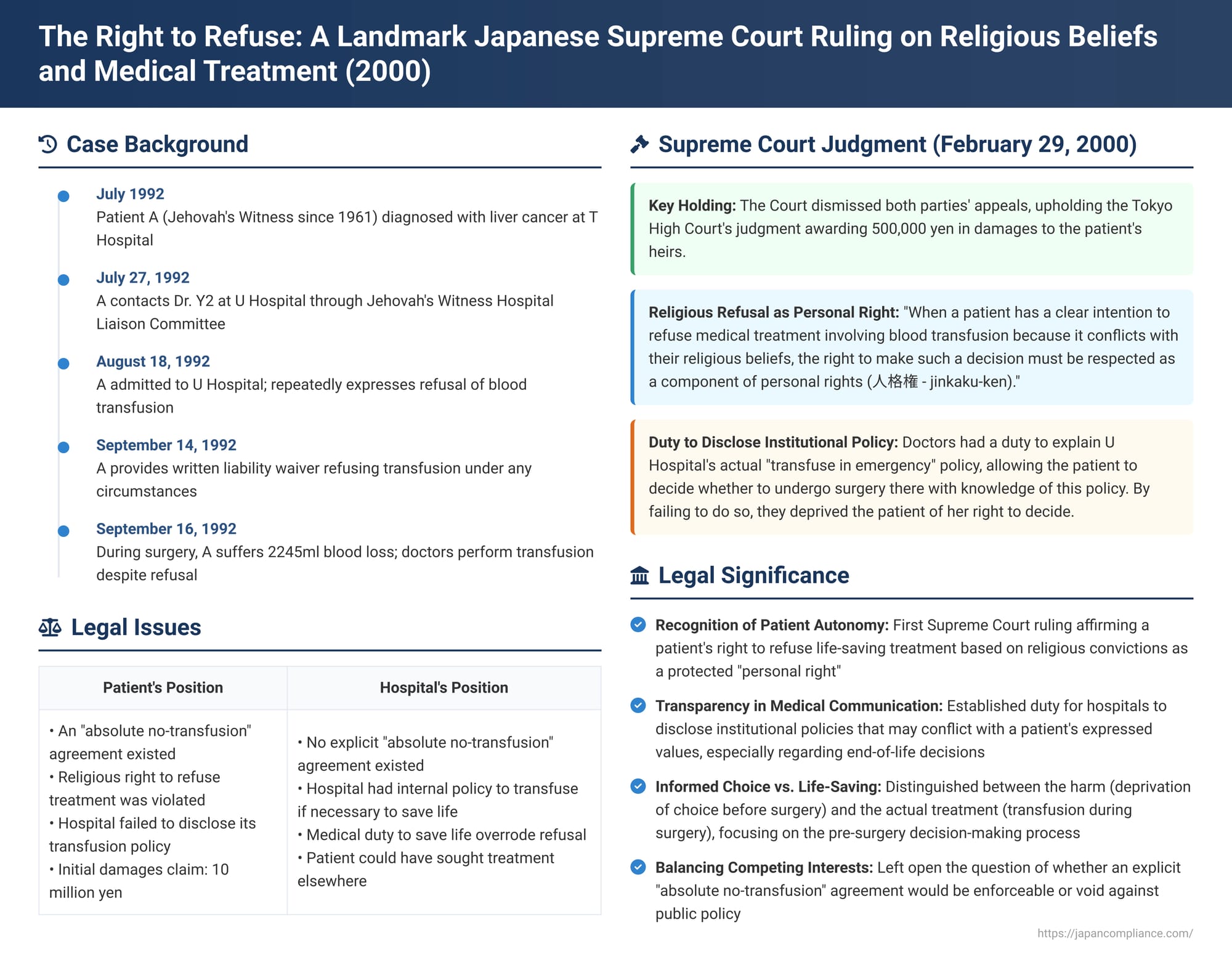

This article examines a pivotal judgment by the Supreme Court of Japan, delivered on February 29, 2000, which addressed the profound conflict between a patient's deeply held religious beliefs and the medical imperative to preserve life. The case involved a member of the Jehovah's Witnesses who, for religious reasons, refused a blood transfusion but was given one during emergency surgery. The Supreme Court's decision delves into the patient's right to self-determination, the scope of informed consent, and the duties of medical professionals when faced with such a dilemma.

The Factual Background: A Test of Faith and Medical Ethics

The patient, A (born in 1929), was a devout Jehovah's Witness since 1961. A core tenet of her faith was the absolute refusal of blood transfusions under any circumstances, a conviction she held firmly. Her husband, X1, though not a Jehovah's Witness, respected his wife's unwavering stance. Their eldest son, X2, was a fellow member of the Jehovah's Witnesses.

In June 1992, A was hospitalized at T Hospital. On July 6, 1992, she received a diagnosis of a malignant liver hemangioma, a type of cancerous tumor in the liver. Physicians at T Hospital informed her that surgery without blood transfusion was not possible. Due to her religious convictions, A discharged herself from T Hospital on July 11 and began searching for a medical facility that would accommodate her refusal of blood.

Through the efforts of the Jehovah's Witness Hospital Liaison Committee, a group that assists believers in finding cooperative medical professionals, contact was made on July 27, 1992, with Dr. Y2, a physician at U Hospital (the University of Tokyo Institute of Medical Science Hospital, operated by U University, the defendant Y). Dr. Y2 was known among the Liaison Committee for having experience in performing surgeries without transfusions. Dr. Y2 agreed to see A, stating that if the cancer had not metastasized, surgery without transfusion might be possible and advised her to undergo tests promptly.

It's important to note U Hospital's internal policy regarding Jehovah's Witness patients undergoing surgery: while the hospital aimed to respect a patient's refusal of blood transfusion and avoid it as much as possible, if a situation arose where transfusion was deemed the only means to save the patient's life, the policy was to administer blood, irrespective of the patient's or their family's consent.

A was admitted to U Hospital on August 18, 1992. Leading up to the surgery, A, her husband X1, and her son X2 repeatedly communicated to Dr. Y2 and his colleagues (the medical team) that A could not receive a blood transfusion under any circumstances. On September 14, 1992, during a meeting where Dr. Y2 explained the surgical procedure and schedule, X2 handed Dr. Y2 a liability waiver document. This document, co-signed by A and her husband X1, explicitly stated that A could not accept blood transfusions and that they would not hold the physicians or hospital staff responsible for any adverse consequences resulting from the withholding of blood.

The surgery to remove the liver tumor (referred to as "the present surgery") was scheduled and performed on September 16, 1992, by Dr. Y2 and two other surgeons. Aware of the potential for significant bleeding and the patient's stance, the medical team nevertheless made preparations for a blood transfusion. During the operation, after the tumor was excised, A experienced substantial blood loss, amounting to approximately 2245 milliliters. The medical team judged that without a blood transfusion, there was a high probability that A's life could not be saved. Consequently, they administered a blood transfusion.

A survived the surgery and was eventually discharged. However, she subsequently filed a lawsuit against U University (Y) and Dr. Y2, seeking 10 million yen in consolation money (damages for emotional distress). Her claim was based on an alleged breach of a medical services contract (specifically, an agreement not to transfuse) or, alternatively, on tort (violation of her right to make her own decisions about medical treatment). A passed away on August 13, 1997, while the case was pending in the appellate court. Her husband X1, and her children X2, X3, and X4, as her legal heirs, took over the litigation.

Lower Court Decisions: A Divergence of Views

The case progressed through two lower courts before reaching the Supreme Court, with differing outcomes:

First Instance Court (Tokyo District Court, judgment March 12, 1997):

The District Court dismissed A's claim. It addressed the assertion that there was a special agreement for "absolute no-transfusion" (meaning no transfusion under any circumstances). The court found that even if such an agreement had been made, it would be void as contrary to public order and good morals (Article 90 of the Civil Code). The court also touched upon the physician's duty to save life. It concluded that the actions of Dr. Y2 and the medical team—proceeding with the surgery while being aware of A's refusal, yet prepared to transfuse to save her life if necessary—could not be deemed illegal under the circumstances. They had, in the court's view, acted in a way that appeared to respect her wishes while retaining the option to intervene to save her life.

High Court (Tokyo High Court, judgment February 9, 1998):

The High Court partially reversed the District Court's decision, finding in favor of A's heirs to a limited extent.

The High Court agreed with the first instance court that no explicit agreement for "absolute no-transfusion" had been formed between A and the hospital/doctors.

However, the High Court found fault with the medical team's conduct in a different respect. It determined that U Hospital and its doctors had a treatment policy of "relative no-transfusion" for Jehovah's Witness patients. This meant they would try to avoid transfusion, but if a life-threatening situation arose where transfusion was the only option to save the patient, they would transfuse. The High Court held that Dr. Y2 and his colleagues had a duty to explain this specific policy to A but had failed to do so.

Due to this failure to explain their actual policy (which differed from A's expectation of an absolute refusal being honored), the High Court found the defendants liable in tort for infringing A's right to make an informed decision. It ordered U University (Y) and Dr. Y2 to pay 500,000 yen in consolation money to A's heirs.

U University (Y) appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, and A's heirs (X1, X2, X3, X4) filed a cross-appeal, presumably arguing for the existence of an absolute no-transfusion agreement and/or a higher amount of damages.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (February 29, 2000)

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed both U University's appeal and the cross-appeal by A's heirs, thereby upholding the Tokyo High Court's decision and its award of 500,000 yen.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

1. The Right to Refuse Medical Treatment as a Personal Right:

The Court laid down a foundational principle: "When a patient has a clear intention to refuse medical treatment involving blood transfusion because it conflicts with their religious beliefs, the right to make such a decision must be respected as a component of personal rights (人格権 - jinkaku-ken)." This was a significant affirmation of patient autonomy in the context of deeply held convictions.

2. The Hospital's and Doctors' Duty of Explanation:

The Court then applied this principle to the specific facts of A's case. It highlighted that:

- A possessed a firm religious belief dictating the refusal of blood transfusion in any situation.

- She was admitted to U Hospital with the expectation that she could undergo surgery without transfusion.

- Dr. Y2 and his colleagues were aware of her steadfast refusal and this expectation.

Given these circumstances, the Supreme Court reasoned that if Dr. Y2 and his team determined that a life-threatening situation necessitating a blood transfusion (as the sole means of saving her life) could not be ruled out during the surgery, they had a specific duty. This duty was to:

- Explain U Hospital's actual policy: They should have informed A that, as an institution, U Hospital's policy was to administer a blood transfusion if such a critical situation arose.

- Allow A to Make an Informed Choice: After this explanation, A should have been allowed to decide for herself whether to continue her admission at U Hospital and undergo the surgery under the care of Dr. Y2 and his team, fully aware of their intention to transfuse in a life-or-death scenario.

3. Breach of the Duty of Explanation:

The Supreme Court found that the medical team had breached this duty. Over approximately one month between A's admission and the surgery, Dr. Y2 and his colleagues recognized that a situation requiring blood transfusion during the operation was a possibility. Despite this recognition, they:

- Failed to explain U Hospital's "transfuse in emergency" policy to A.

- Proceeded with the surgery without informing A or her family (X1 and X2) that a transfusion might be performed.

- Subsequently administered the transfusion in accordance with this undisclosed internal policy.

4. Infringement of Personal Rights and Liability:

The Court concluded: "In this case, by neglecting the aforementioned explanation, Dr. Y2 and his colleagues must be said to have deprived A of her right to decide whether or not to undergo the present surgery, which carried the possibility of a blood transfusion. In this respect, they infringed her personal rights and should be held liable to compensate for the emotional distress she thereby suffered."

Consequently, U University (Y), as the employer of Dr. Y2 and the medical team, was held vicariously liable for their tortious act under Article 715 of the Civil Code. The Supreme Court found no error in the High Court's judgment to this effect.

5. Regarding the Cross-Appeal by A's Heirs:

The Supreme Court also addressed the cross-appeal filed by A's heirs. This appeal likely contested the High Court's finding that no "absolute no-transfusion" agreement was formed and challenged the adequacy of the 500,000 yen damages award. The Supreme Court summarily upheld the High Court's findings of fact and its determination of the damages amount, stating that the High Court's decisions on these matters were justifiable based on the evidence and were within its discretionary powers. It found no legal violations in the High Court's reasoning on these points.

Analysis and Implications: Navigating a Complex Ethical and Legal Terrain

The Supreme Court's decision in this "Jehovah's Witness blood transfusion refusal case" carries significant implications for medical practice, patient rights, and the understanding of informed consent in Japan.

Patient Autonomy and Personal Rights: The judgment's explicit recognition of the right to refuse medical treatment based on religious beliefs as a "personal right" is a cornerstone of this ruling. It affirms that individuals have a fundamental interest in making decisions about their own bodies and medical care, even if those decisions diverge from conventional medical advice or appear to carry increased risks from a purely clinical perspective.

The Crucial Role of Clear Communication and Disclosure: The case hinges not on whether the transfusion was medically necessary to save A's life in that moment (which the doctors believed it was), but on the failure of communication before that crisis point. The hospital had an internal policy that was directly relevant to A's expressed wishes and expectations. The failure to disclose this policy was the central flaw. This underscores that informed consent requires a transparent dialogue where hospitals and doctors clearly communicate any institutional policies or treatment approaches that might conflict with a patient's known values or directives. Patients cannot make truly informed choices based on incomplete or withheld information.

The Nature of the Infringed Right: The harm identified by the Supreme Court was the deprivation of A's "right to decide whether or not to undergo the present surgery" under the conditions that might include a transfusion. This is a subtle but crucial distinction. The infringement was the violation of her autonomy before the surgery, by denying her the information needed to make a choice consistent with her values. Had she been informed of the hospital's policy, she could have chosen:

* To accept the risk and proceed with the surgery at U Hospital.

* To refuse surgery at U Hospital and seek another institution or alternative treatments, however slim those chances might have been.

* To make other personal arrangements or preparations.

The core injury was the loss of this agency.

Scope and Limitations of the Ruling: While a landmark decision, its direct applicability might be nuanced in different factual scenarios. The ruling itself notes it is based on "the factual circumstances of this case". This implies caution in extrapolating it to situations where, for example:

- The patient's wishes are unknown or unclear (e.g., an unconscious emergency patient).

- There is absolutely no time to ascertain wishes or discuss policies in an immediate life-threatening crisis.

- The patient lacks the capacity to make such a decision (though this raises further complex issues about advance directives and surrogate decision-makers).

- The refusal is for reasons other than deeply held religious or personal convictions.

The Adequacy of Damages: The High Court awarded, and the Supreme Court upheld, 500,000 yen (roughly USD 4,000-5,000 at the time) for the infringement of A's personal right to decide and the resulting emotional distress. Legal commentators and patient advocates have often debated whether such sums are sufficient to adequately compensate for the violation of such a fundamental right or to serve as a significant deterrent against future failures in the informed consent process. The argument is that if damages for violating the right to self-determination are too low, it might not sufficiently incentivize robust adherence to disclosure duties.

The Unresolved "Absolute No-Transfusion" Agreement: The courts found that an explicit, binding contract for "absolute no-transfusion" (i.e., a promise by the hospital not to transfuse even if life-saving) was not factually established. This leaves open questions about whether such an agreement, if unequivocally proven, would be considered enforceable or void against public policy, an issue the first instance court touched upon but the higher courts did not need to definitively resolve due to their factual findings.

Conclusion

The February 29, 2000, Supreme Court judgment in the Jehovah's Witness transfusion refusal case marks a significant moment in the evolution of patient rights and medical law in Japan. It firmly establishes that a patient's clear and conscientiously held decision to refuse specific medical treatments, even life-sustaining ones, is a personal right that demands respect.

The ruling's enduring legacy lies in its emphasis on the paramount importance of transparent and honest communication between medical professionals and patients. It mandates that doctors and hospitals disclose their treatment philosophies and policies, especially when these may diverge from a patient's expressed wishes or expectations. By doing so, the medical profession can ensure that patients are truly empowered to make autonomous decisions that align with their own values and beliefs, even in the most challenging and critical medical circumstances. This case serves as a continuing reminder that the process of informed consent is not a mere procedural hurdle but a fundamental dialogue that upholds the dignity and autonomy of the patient.