The Right to Reconsider: Japan's Supreme Court on Informed Consent for Unruptured Brain Aneurysms

Date of Judgment: October 27, 2006

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, 2005 (Ju) No. 1612

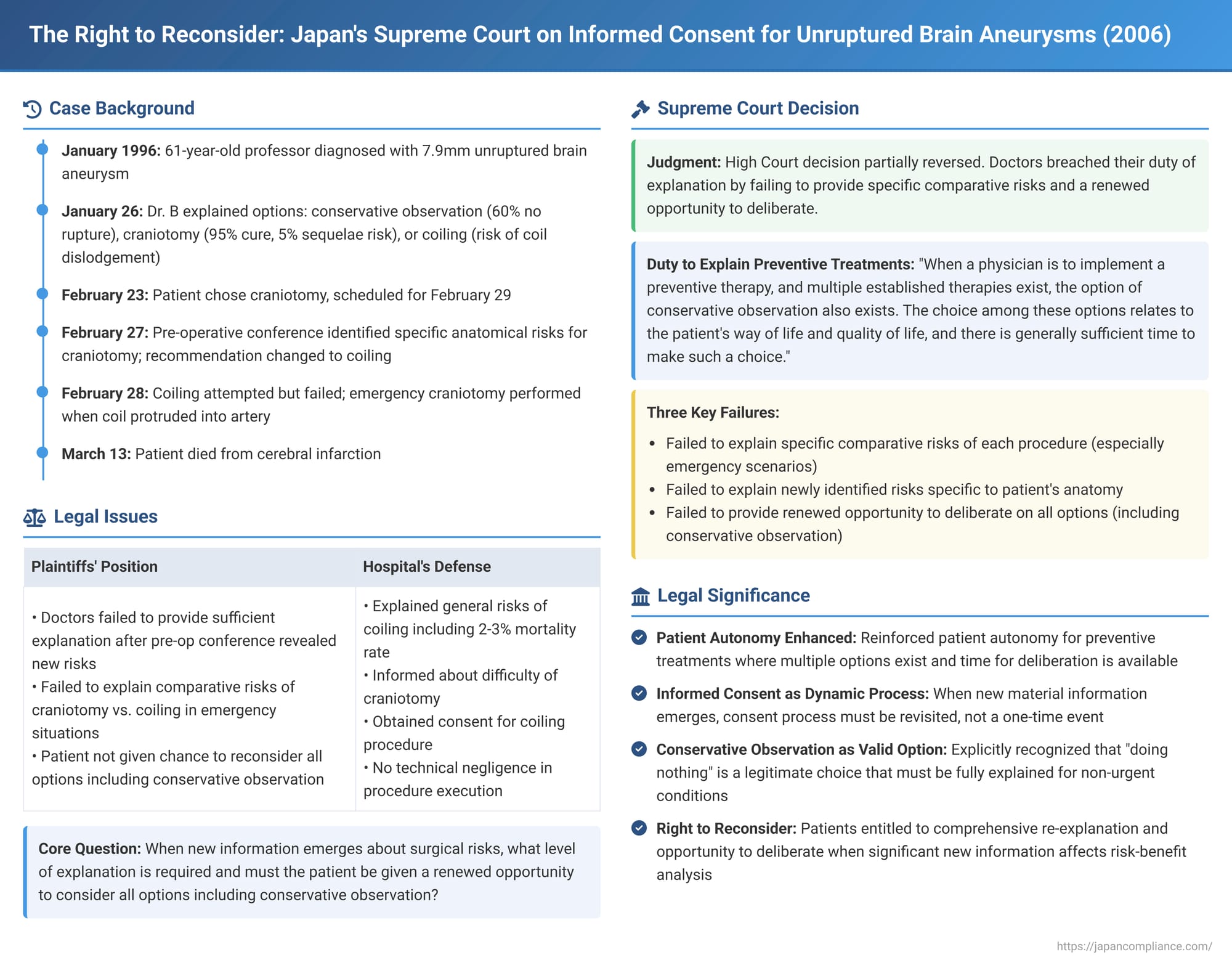

In a significant ruling on October 27, 2006, the Supreme Court of Japan provided crucial clarifications on a physician's duty of explanation, particularly when dealing with non-urgent, preventive medical treatments where multiple established options, including conservative observation, exist. The case involved a patient with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm who tragically died after complications from a recommended procedure. The Court's decision emphasized the patient's right to a thorough understanding of all viable choices and the necessity of a renewed opportunity for deliberation when new, relevant medical information emerges.

The Factual Background: A Shifting Landscape of Risk and Choice

The patient, A, a 61-year-old university professor, was suspected of having a cerebral aneurysm after experiencing a transient ischemic attack. In January of Heisei Year 8 (1996), an aneurysm was confirmed at the bifurcation of his left internal carotid artery, measuring approximately 7.9 mm on the day of the eventual surgery. This was an asymptomatic, unruptured brain aneurysm.

At that time, the established medical options for such a condition were:

- Conservative Observation: Monitoring the aneurysm without immediate intervention.

- Craniotomy (Clipping): An open-skull surgery to place a clip at the neck of the aneurysm to prevent blood flow into it.

- Endovascular Coiling (Embolization): A less invasive procedure where coils are inserted into the aneurysm via a catheter to induce clotting and seal it off.

On January 26, Heisei 8, Dr. B, a neurosurgeon at N Hospital (operated by defendant Y, N University), provided the following explanation to A and his wife, X1:

- Aneurysm Behavior: If left untreated, 60% of such aneurysms do not rupture, allowing continued normal life. However, 40% carry a risk of rupturing within the next 20 years.

- Treatment Methods: If treatment is pursued, two methods are available: craniotomy and coiling.

- Craniotomy Outcomes: Offers a 95% chance of complete cure, but a 5% risk of permanent neurological deficits (sequelae).

- Coiling Risks: There's a possibility that the coils could later dislodge from the aneurysm and cause a cerebral infarction (stroke).

- Patient's Choice & Timing: The decision of whether to opt for conservative observation, craniotomy, or coiling rests with the patient. Furthermore, even if treatment is chosen, it doesn't have to be immediate and could be undertaken some years later.

Following this explanation, on February 23, A informed Dr. B that he wished to proceed with a craniotomy. The surgery was scheduled for February 29.

However, events took a significant turn at a pre-operative conference held on February 27. Professor D at N Hospital, after reviewing A's cerebral angiograms, raised serious concerns. He noted the specific anatomy of A's internal carotid artery (described as "standing up") and the way the body of the aneurysm was embedded within the brain tissue. This led him to believe that the posterior aspect of the aneurysm's body would likely not be visible during surgery. Consequently, there was a significant risk that attempts to clip the aneurysm might inadvertently occlude vital perforating arteries or the anterior choroidal artery (this specific risk was termed the "occlusion possibility"). Professor D concluded that craniotomy for A would be "considerably difficult." He proposed that, given it was an unruptured aneurysm (as opposed to a ruptured one where craniotomy might be the first choice despite difficulty), it would be advisable to attempt endovascular coiling first. If coiling was unsuccessful, then craniotomy could be reconsidered after a thorough discussion with A and his family about the potential neurological risks. This proposal to try coiling first became the hospital's revised plan.

Later that same day (February 27), Dr. B and another physician, Dr. C (a specialist in coiling), spent approximately 30 to 40 minutes explaining the new situation to A and X1, now recommending the coiling procedure:

- Reason for Change: They conveyed that the pre-operative conference had concluded A's aneurysm was in a location that made craniotomy difficult and dangerous, and therefore, the team suggested trying coiling.

- Advantage of Coiling: They highlighted that coiling offered the significant benefit of avoiding an open-skull surgery.

- Dr. C's Experience: Dr. C stated that he had performed coiling procedures in over a dozen cases, all of which had been successful.

- A's Query: A specifically asked about the previously mentioned risk of coils dislodging and causing a stroke. Dr. C responded that if the procedure did not go smoothly, they would not force the issue; they would immediately retrieve the coils and develop a new plan.

- General Coiling Risks Explained by This Time: It was also established that by this point, A and X1 had been informed that coiling carried risks of complications, including cerebral infarction (stroke) which could occur during or after the procedure, and that the mortality risk from such complications was estimated at 2-3%.

That evening, A and X1 consented to the endovascular coiling procedure.

The Procedure and Tragic Outcome

On February 28, Heisei 8, after a preliminary angiogram confirmed that coiling was feasible for A, Dr. C commenced the procedure. However, during the insertion, a portion of the coil protruded from the aneurysm into the parent artery (the internal carotid artery), creating a risk of blocking blood flow and causing a major stroke. The coiling procedure was immediately aborted. Efforts were made to retrieve the dislodged coil using a retrieval device, but these were unsuccessful because a knot had formed in the coils within the aneurysm.

Consequently, an emergency craniotomy was performed by the neurosurgical team (including Dr. B) to remove the wayward coils. While the coils within the aneurysm were successfully removed, the portion that had migrated into the internal carotid artery could not be extracted due to the risk of tearing the artery.

A never regained consciousness after the craniotomy. He suffered a massive cerebral infarction caused by the impaired blood flow from the dislodged coil. He was declared brain dead on March 1 and passed away on March 13, Heisei 8.

A's wife (X1) and his children (X2 and X3) subsequently sued Y (the hospital operator, N University) for damages. They alleged negligence in the performance of the coiling procedure (technical skill) and a breach of the duty of explanation by the attending physicians.

Lower Court Proceedings: Conflicting Views on Duty of Explanation

First Instance (Tokyo District Court): The District Court found no negligence in the technical execution of the coiling procedure. However, it did find that the doctors had breached their duty of explanation by not sufficiently detailing the intraoperative risks of coiling. The court found a causal link between this insufficient explanation and A's death, awarding partial damages (reduced by 30% to account for the inherent future risk of the aneurysm rupturing even if untreated).

High Court (Tokyo High Court): On appeal, the High Court also found no technical negligence. However, it overturned the District Court's finding on the duty of explanation. The High Court concluded that the risks of complications from coiling, including intraoperative risks and the frequency of death, had been explained. Therefore, it found no breach of the duty of explanation and dismissed the plaintiffs' claim entirely. The plaintiffs then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (October 27, 2006)

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's decision. It agreed with the lower courts regarding the absence of technical negligence (this part of the appeal was not accepted for review). However, it found that the High Court had erred in its judgment concerning the doctors' duty of explanation and remanded this aspect of the case back to the Tokyo High Court for reconsideration.

The Supreme Court's reasoning for reversing the High Court on the duty of explanation was meticulous:

1. General Duty to Explain Treatment Options:

The Court began by reaffirming an established principle from its prior jurisprudence (notably, the Supreme Court judgment of November 27, 2001, concerning breast cancer treatment options): When multiple medically established therapies or surgical procedures exist for a patient's condition, physicians have a duty to explain the differences between each therapy/procedure, including their respective risks and benefits, in a manner that is understandable to the patient. This is to enable the patient to make a considered decision after careful deliberation.

2. Specific Duty Regarding Preventive Therapies and Conservative Observation:

The Court then extended this principle with particular emphasis on situations involving preventive (prophylactic) therapies, such as the treatment of an unruptured aneurysm. It stated:

"When a physician is to implement a preventive therapy (or procedure) for a patient, and multiple medically established therapies (or procedures) exist, then along with the option of undergoing one of these therapies, the option of not undergoing any therapy and being conservatively monitored also exists. The choice among these options can relate to the patient’s own way of life and quality of life, and there is also generally sufficient time to make such a choice. Therefore, so that the patient can make a judgment after careful deliberation on which option to select, the physician is required to explain in an easy-to-understand manner the differences between each therapy (or procedure) and the respective advantages and disadvantages of each option, including conservative observation."

3. Application to A's Case and Identified Deficiencies in Explanation:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court identified several critical shortcomings in the explanations provided to A:

- (a) Nature of Treatment: A's aneurysm treatment was preventive, and at the time, craniotomy and coiling were both established medical options. (The Court also noted an expert opinion that coiling was then a relatively new treatment modality ).

- (b) Deficient Comparative Risk Explanation: The Court found that the N Hospital doctors should have possessed, and had a duty to clearly explain to A, the following comparative insights, which were considered standard knowledge for specialists performing these procedures:

- Craniotomy: Carries a risk of intraoperative nerve damage. However, if the aneurysm were to rupture during the craniotomy procedure, it is generally easier to manage and address the situation compared to a rupture during coiling.

- Coiling: Is less physically invasive than craniotomy and has a lower risk of direct intraoperative nerve damage. However, it carries the risk of causing an embolism (blockage leading to stroke). Furthermore, if the aneurysm were to rupture during the coiling procedure, it is often very difficult to save the patient, and an emergency craniotomy would become necessary anyway.

The Supreme Court stated that the doctors had a duty to explain at least these respective risks and benefits clearly.

- (c) Failure to Explain Newly Identified Craniotomy Risks Specific to A: After A had initially chosen craniotomy, the pre-operative conference on February 27 revealed new information: that craniotomy for A would be "considerably difficult" due to the aneurysm's specific location and the "occlusion possibility" (the risk of inadvertently blocking crucial small arteries). The doctors had a duty to specifically and concretely explain these newly identified problems and heightened risks associated with craniotomy for A's particular case. This was necessary so that A could properly compare the risks of craniotomy (now understood to be more dangerous for him than initially thought) against the risks of coiling.

- (d) The Crucial Lack of a Renewed Opportunity for Deliberation: Based on the deficiencies (b) and (c), the Supreme Court concluded: "The attending physicians at N Hospital had a duty to provide explanations (b) and (c) to A, and thereafter, to provide him with a renewed opportunity to carefully deliberate on which option to choose: craniotomy, endovascular coiling, or to undergo neither surgery and opt for conservative observation."

- (e) Prior Explanations Insufficient: The explanations provided to A on January 26 (points ① to ⑤) and on February 27 after the conference (points ⑥ to ⑩, including the general 2-3% mortality risk for coiling) were deemed insufficient to meet this comprehensive duty. The determination of whether there was a breach of the duty of explanation should be based on whether the specific detailed explanations (b) and (c) were provided, whether the renewed opportunity for deliberation (d) was given, and if not, whether there were any special circumstances that justified not providing them.

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred by not thoroughly examining these specific points and by concluding there was no breach of duty based merely on the explanations that were given, especially in light of the sudden shift in recommendation from craniotomy to coiling just before the scheduled surgery.

Analysis and Implications: Deepening the Understanding of Informed Consent

This Supreme Court decision significantly refines the understanding of informed consent in Japanese medical law, with several important implications:

- Reinforcement of Patient Autonomy in Non-Urgent Settings: The ruling strongly champions patient autonomy, especially when treatment is preventive and there is adequate time for deliberation. The patient's "way of life and quality of life" are explicitly recognized as relevant factors in their decision-making process.

- Informed Consent as a Dynamic Process: This case highlights that informed consent is not a one-time event. When new, material information arises that could alter a patient's understanding of the risks and benefits of different options (as the conference findings did regarding craniotomy for A), the consent process must be revisited. Patients must be given the chance to integrate this new information into their decision-making.

- The Importance of Explaining "Doing Nothing" (Conservative Observation): A key takeaway is the explicit duty to include "conservative observation" as one of the options to be fully explained when it is a medically accepted approach for a non-urgent, preventive treatment. Patients have the right to understand the implications of choosing no active intervention.

- Specificity in Comparative Explanations: The Court demanded a high degree of specificity in explaining the comparative risks and benefits. This included not just general success rates or complication percentages, but also nuanced scenarios like how an intraoperative aneurysm rupture would be managed differently and with different prognoses depending on whether craniotomy or coiling was being performed. It also required disclosure of patient-specific difficulties (like the "occlusion possibility" for A's craniotomy).

- The "Renewed Opportunity to Deliberate": This concept is central. It wasn't enough for the doctors to simply present the new recommendation (coiling) and its rationale. They needed to step back and allow the patient to re-evaluate all available paths – the initially chosen one (now with newly understood risks), the newly recommended one, and the option of no immediate intervention – with the benefit of all current information.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of October 27, 2006, serves as a critical benchmark for the duty of explanation in Japanese medical practice. It clarifies that for preventive treatments with multiple established options, physicians must not only detail the specifics of each active intervention but also thoroughly explain the alternative of conservative observation. Perhaps most importantly, it establishes that if significant new information comes to light that materially affects the risk-benefit analysis of previously discussed options, patients are entitled to a comprehensive re-explanation and a fresh opportunity to deliberate on all available choices. This ruling robustly supports a patient-centered approach to medical decision-making, ensuring that choices are made with the fullest possible understanding and respect for individual autonomy.